“When it came out, all we got was indifference and accusations that we’d sold out. Now it’s worshipped”: The brutal story of Carcass’s early 90s death metal classic Heartwork

Hash pipes, bust-ups and a death metal landmark – how Carcass made 1993’s classic Heartwork album

Emerging from the late 80s grindcore scene, by the early 90s Carcass had transformed into a surgically-fixated death metal band – and 1993’s Heartwork album remains a landmark of the genre. In 2007, bassist and vocalist Jeff Walker looked back on a record that helped change the course of extreme metal.

Someone once jokingly suggested that Carcass were the most important British band since the Sex Pistols. That might be an exaggeration, but there’s no doubt that the band that rose from the UK’s subterranean crust-punk and grindcore scene went on to become one of the the most significant inspirations on the death metal movement.

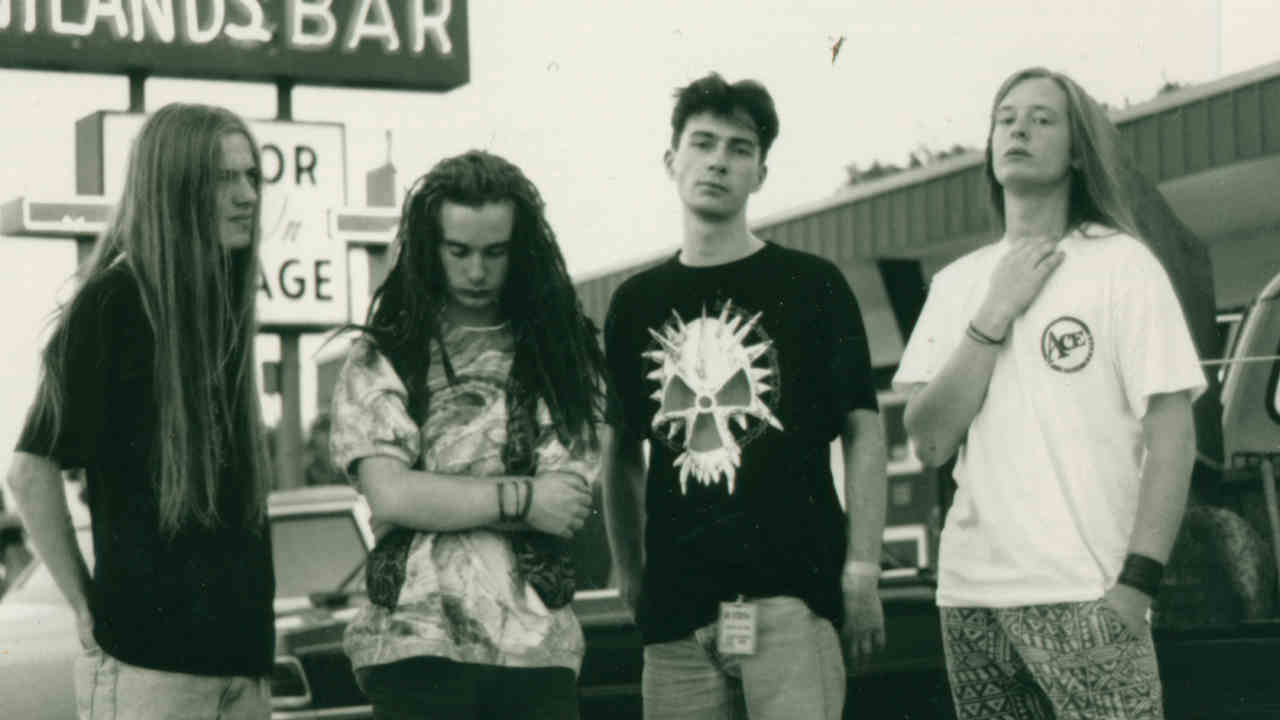

It was unthinkable when Carcass – bassist Jeff Walker, guitarist Bill Steer and drummer Ken Owen, all of whom shared vocals during the early days – formed on Merseyside in the mid-80s (Steer spent a few years pulling double duty in Napalm Death). Their debut album, 1988’s Reek Of Putrefaction was released on underground UK label Earache and featured songs with such vivid titles as Regurgitation Of Giblets, Vomited Anal Tract and Microwaved Uterogestation, as well as a gore-splattered cover.

Its lower-than-lo-fi production sounded like it had been recorded for the cost of a bag of chips, but it helped Carcass attract the attention of influential DJ John Peel, who gave them a session on his Radio One show in 1989. Their second album, Symphonies Of Sickness, was released the same year, showcasing an altogether more cohesive and developed style, thanks in part to producer Colin Richardson.

Two years later, with Swedish guitarist Mike Amott now added to the line-up, Necroticism – Descanting The Insalubrious (once again produced by Colin Richardson) took Carcass further away from their ultra-extreme roots, sounding comparatively more palatable to those whose metal tastes were a little more refined. It was the precursor for the musical leap that would come with their fourth album, 1993’s Heartwork.

“I don’t think there’s any doubt that this album has been a major influence on all grind and death metal bands – you’ve only gotta hear so much that’s released these days to realise this,” says Jeff Walker. “But it must be a little odd for people like Bill and Mike when guitarists like Gary Holt of Exodus rave about that record – he was a major inspiration for them.”

Work on Heartwork actually started even as the band were touring on the back of Necroticism…. They’d wasted no time in getting stuck into the new project, with the belief that what they were doing was moving everything to another level, rather than taking a radical shift in emphasis.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I suppose what we were really doing was going for shorter songs,” says Walker. “By the time Symphonies Of Sickness came out, we were getting almost progressive, in the way that the tracks were so long. When Mike arrived for Necroticism…, we were beginning to write songs that were less wandering, and they were certainly going down rather well with the fans. Not that we weren’t capable of being complex or technical – something like Arbeit Macht Fleisch on Heartwork proved that to be the case.”

The band had the whole album demoed by the time they toured in Europe with Death and Cannibal Corpse in the spring of 1993. “We did it at Parr Studios in Liverpool – in Studio Three, to be precise, which was the smallest room there,” says Jeff. “And I had a slight vocal problem at the time. You see, I’d been to see Brutal Truth and Cathedral play, and had a hash pipe afterwards – that caused the problem. The demo versions of the songs were a lot rawer than the album ones – and I have to say that I prefer them. The production was more basic and seemed to suit what we were doing.”

Carcass surprised everyone by playing all of the new songs on that tour, despite Jeff’s objections. “All the others wanted to do it, but I never saw the point,” he says. “The fans had never heard the tracks before, so why would we fill up our set with them? But I was outvoted and they did go down really well.”

Heartwork would be the first Carcass album that didn’t feature any vocals from Bill Steer – in the early days, the guitarist shared singing duties with Jeff and Ken. Legend has it that this was because producer Colin Richardson felt that Jeff’s style was much more in tune with the direction the band were taking. Not so, insists the frontman.

“Bill made the decision himself,” says Walker. “He just wanted to concentrate on his guitar playing. We all tried hard to persuade him to sing on the record – and by ‘we’ I am including Colin. But he refused to budge.

“It all came to a head when, one day, we were going on at him so much that Bill walked out of the studio and came back an hour later. I think he’d made his point that this wasn’t something he was prepared to discuss, and the matter was never mentioned again.

“If I’m honest, I think the album suffered from not having his vocals on it – all you got were mine, and I don’t believe that was enough.”

There was, however, an issue with Colin Richardson. The band considered not using him, instead producing themselves under the guidance of house engineer Keith Andrews.

“Colin was at Parr producing a band called Disincarnate, who had one-time Death guitarist James Murphy in their line-up,” says Jeff. “And to be straight about it, we were fed up with the way that Colin was diluting what we did by working with what I’d call second-rate bands. It really was getting to us. Somehow, we believed he was insulting Carcass by taking any old job going. We decided to go down to the studio, and tell him that he wasn’t gonna do Heartwork.

“Colin talked us round. Simple as that. He convinced us that he was still the best man for the job, and eventually we agreed to keep him on. It was lucky that nobody else had been asked to produce the record! For instance, on that Death/Cannibal Corpse tour, all the bands shared a bus, and the sound engineer was Scott Burns – also a top producer in his own right!”

Carcass spent a month between May and June 1993 recording Heartwork. For the most part, it was a smooth operation. Although they did have huge trouble getting a good guitar sound.

“Tell me about it!” laughs Jeff. “We spent two, or maybe even three days trying everything. That’s at a cost of £100 per day, which to us was expensive. Nothing worked. Until we had the bright idea of going into Studio Three, where we’d done the demo, and got a good guitar sound right away!

“It always amuses me when I hear from bands how they spend ages and a lot of money trying to get a guitar sound like that on Heartwork. Now they know the truth… we did it in the smallest, cheapest room at Parr!”

Heartwork was released in October 1993, with a cover featuring a photo of a sculpture by renowned Swiss artist HR Giger. It charted at number 54 in the UK – the first time the band had made the Top 100. But celebrations were cut just a little short when Mike Amott left.

“Mike had already told our manager, Martin Nesbitt, that his heart lay in this new project he had called Spiritual Beggars, and that he planned on leaving after the Heartwork tour,” says Jeff. “On top of that, he’d been stuck in Israel for ages because his passport and equipment had been locked away due to some unpaid bills. He only just got back to England in time to do his solos.

“Taking all of this into account, Bill and I felt it was better for Mike to leave before the tour, rather than dragging it all out. The guy we had lined up was Mike Hickey, who had been a roadie for us. He brought a real injection of energy and enthusiasm, which was something we’d been missing for a while, if the truth be told. It was a pleasure to play with someone who cared.”

However, the problems for Carcass didn’t end there. In America, their label, Earache, had done a licensing deal with the mighty Columbia corporation for the release of all the label’s records, but Jeff was not happy with the way things were handled out there.

“Columbia had no choice under the terms of the agreement but to release everything Earache gave them. However, it was obvious they didn’t give a shit. At times, we felt like we’d been thrown into a Spinal Tap scenario, meeting all of these executives who didn’t know who we were – and didn’t care. We actually signed direct to Columbia for our next album [Swansong], but it was all a disaster.”

Today, Heartwork stands as a landmark death metal record, mixing melodicism with brutality. Together with the Gothenburg Scene, which was bubbling up in parallel at the same time, it pointed the way towards death metal’s future. Carcass themselves split in 1996, before the release of the aptly-titled Swansong album, but reunited in 2007 (sadly, Ken Owen was unable to participate, after suffering a cerebral haemorrhage in 1999).

So, with the advantage of hindsight, how does Jeff view the Heartwork album now? Was it innovative? Is it the band’s finest hour?

“To answer the latter first – no, it wasn’t. Not for me anyway. I much prefer the Reek Of Putrefaction and Symphonies Of Sickness era. But if you ask Mike, I guess he’d say this one stands out. But its influence is clear, and without it the whole melodic death metal movement might never have happened. Typical though, isn’t it? When it came out, all we got was indifference, and a lot of accusations that Carcass had ‘sold out’. Now it’s worshipped. It’s a record that people have only grown to appreciate after a long time. That says a lot about trends.”

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue 174, December 2007

Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for Record Mirror magazine in the late 70s and Metal Fury in the early 80s before joining Kerrang! at its launch in 1981. His first book, Encyclopedia Metallica, published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year. Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the Anthrax song Metal Thrashing Mad in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. He died in 2021.