“We took it badly – ‘No one wants us any more!’ We’d never been through the school of hard knocks. We didn’t know what it meant to work hard”: When ELP collapsed, Carl Palmer’s career-long lucky streak ended. But he didn’t give up

Born into a musical family and a pro by his teenage years with a real-life education in backstage realities, the passionate drummer has seen dreams come true with Arthur Brown, Atomic Rooster, Asia, Mike Oldfield and others

Prog was delighted to present Carl Palmer with 2017’s Prog God Award at the Progressive Music Awards. Sadly the last surviving member of Emerson Lake & Palmer, the drummer has worked with some of the biggest names in prog and influenced many others. Ahead of the presentation ceremony he looked back on his career to date.

When the greats of modern music reach pensionable age, it seems reasonable to expect everything to slow down a little. Enthusiasm for touring the world and churning out new music often diminishes as the years pass and energy levels inevitably start to flag. That’s how things work for most veteran musicians – but Carl Palmer is not most musicians. Now aged 67, the man who has conquered the music world on at least two separate occasions has never seemed less likely to ease off on the accelerator.

He speaks to Prog a matter of hours after returning home after an extensive tour with Asia (now fronted by Billy Sherwood, in the wake of former incumbent John Wetton’s death in January 2017) as main support to AOR legends Journey. Within days of concluding our conversation, he’ll be off again to play shows with his own current band, Carl Palmer’s ELP Legacy.

He sounds like a man with no time to waste: he speaks quickly, eager to affirm how lucky he feels to have pursued his greatest love for the last 50 years. Above all, he sounds thrilled to still be making a living from playing the drums – something he was plainly destined to do.

“I don’t want to sound too blasé, but it was like a duck to water thing for me,” Palmer says. “I actually started off playing banjo when I was five, had a go on the violin when I was 10 and moved to the drum set when I was 11. My great-grandfather was a drummer. His brother was also a professional musician – he conducted at the London Palladium and was a Professor of Music at the Royal Academy. Their mother was a classical guitar player, so that’s where the line came from.

“I learned by ear to start with, but then I got a teacher and learned to read. My family thought that as long as you could read music, you always had a chance of getting a job somewhere. There was no thought of being a Prog God back then!”

Convinced he was destined to make a living as a jobbing drummer, Palmer began to pay his dues as a member of the orchestra at the local Locarno club. Although increasingly entranced by the somewhat rowdier guitar-based music that was starting to grab the world’s attention, his apprenticeship was firmly in the realms of trad jazz and ballroom dancing.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I’d play Glenn Miller one night, formation dancing the next, then Latin night, and then my favourite, which was Top Of The Pops night. I’d get the chance to play all the stuff I’d seen on TV the week before – The Kinks or whatever it was. I’d been working for eight months or so, playing in traditional jazz groups and blues groups, but I’d never really been in a band with guitars.”

He remained blissfully unaware of the glories to come as he made his first steps into the world of bona fide rock’n’roll. In 1964, he spotted a ‘drummer wanted’ ad in the local paper and decided to give it his best shot, heading straight to the local ballroom where The King Bees were holding auditions.

“I was late, actually!” Palmer chuckles. “The ballroom was just a 15-minute walk from the house in Birmingham, but when I got there they’d finished the audition and were packing the equipment away. They asked if I still wanted to try out. They gave me a pile of 45s and said, ‘Do you wanna take these home and learn them?’ So I went back and put the records on and they waited for me. I came back and played through everything they wanted and they were amazed! But it was very easy, to be honest. I didn’t understand the drama! So that was it. I joined them and played with them right up until I left school.”

With the rock’n’roll bit between his teeth, he soon made his next step towards the big time. In 1966, fresh from having a No.1 hit with his version of The Rolling Stones’ Out Of Time, London’s finest rock’n’soul singer, Chris Farlowe, was auditioning for a new drummer. Barely through the school gates as his final term ended, Palmer admits he fancied his chances, but was still pleasantly surprised to strike gold again.

Our agent would say, ‘I was going to pick your money up for you!’ and he was going to pocket an extra £200… I saw all that from a young age

“I have to admit it was a really easy start for me. I left school on the Friday, had my audition the next Wednesday at the Bag O’ Nails in Kingly Street, and by the following Friday I was somewhere in Germany, playing with Chris at the Star-Club in Hamburg. That was my first real professional job. I think I had my 16th birthday in Germany. I was playing with people like Dave Greenslade, Albert Lee… These were great players, so it was a brilliant way to start.”

Five decades on from those formative days, Palmer’s reputation as one of the greatest drummers of all time is almost equalled by his reputation for taking care of business. Famously clean-living – he claims never to have smoked or drunk a pint of lager, let alone indulged in anything more illicit – he looks far leaner and healthier than most of us will (or do) at 67 years of age, and has clearly benefited from having his eyes wide open throughout his career.

“I remember the first time I saw the way things really worked,” he says. “Agents would give us a contract stating one sum of money. I’d go with Chris Farlowe to see the promoter and Chris would pick up an extra £200 on top of the agreed fee, because that’s what the promoter had was on his contract. Then our agent would come in the back door and say, ‘Oh Chris, I came up for the day to see you… I was going to come and pick your money up for you!’ and obviously he was going to pocket the extra £200. So I saw all that from a young age. It was a proper learning curve and I enjoyed every minute of it.”

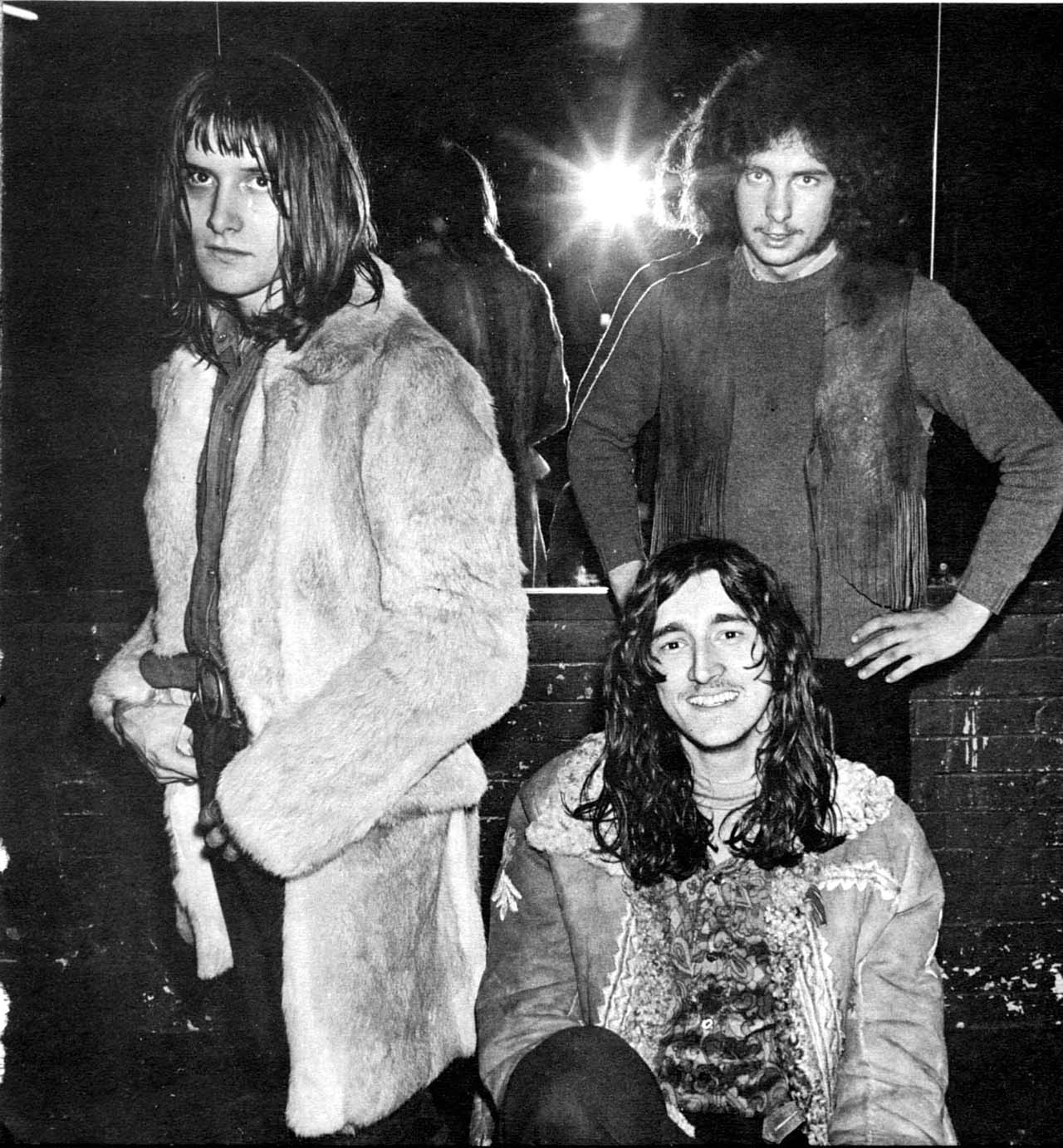

Hell-bent on earning himself an unbeatable CV, between 1967 and 1969, Palmer was a member of The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown, starting with a US tour that followed the band’s sudden presence at the top of charts on both sides of the Atlantic. Torn between taking a punt on something new and sticking with the more secure Chris Farlowe gig, the still-teenage drummer once again considered himself a very lucky boy.

“I was a bit apprehensive about going to the States with Arthur Brown,” he admits. “But it was a good offer, so I said to Chris, ‘Look, I’ve got this opportunity; if I go and I don’t like it, can I have my job back when I return?’ It was a bold move – but I figured that you’ve got to try!

“He said, ‘Yeah, you can, but you’ve got to find me a new drummer and he’s got to be really good!’ I said, ‘Yeah, I can find someone,’ and that was the first job that I handed to my mate John Bonham. He jumped at the chance because it was a regular job that paid 40 quid a week.”

After two years playing drums for a man with (if you’ll pardon our French) a flaming helmet, Palmer felt it was time to move on; and, ever the pragmatist, he took Brown’s keyboard maestro Vincent Crane with him and formed Atomic Rooster.

The underground prog rock movement was still in its infancy at that point, but both Palmer with his new band, and Keith Emerson with The Nice, were making waves at a critical moment in music’s evolution.

In 1970, after building up a sizeable following in the UK and northern Europe, Atomic Rooster started work on songs for their second studio album; but destiny had other ideas.

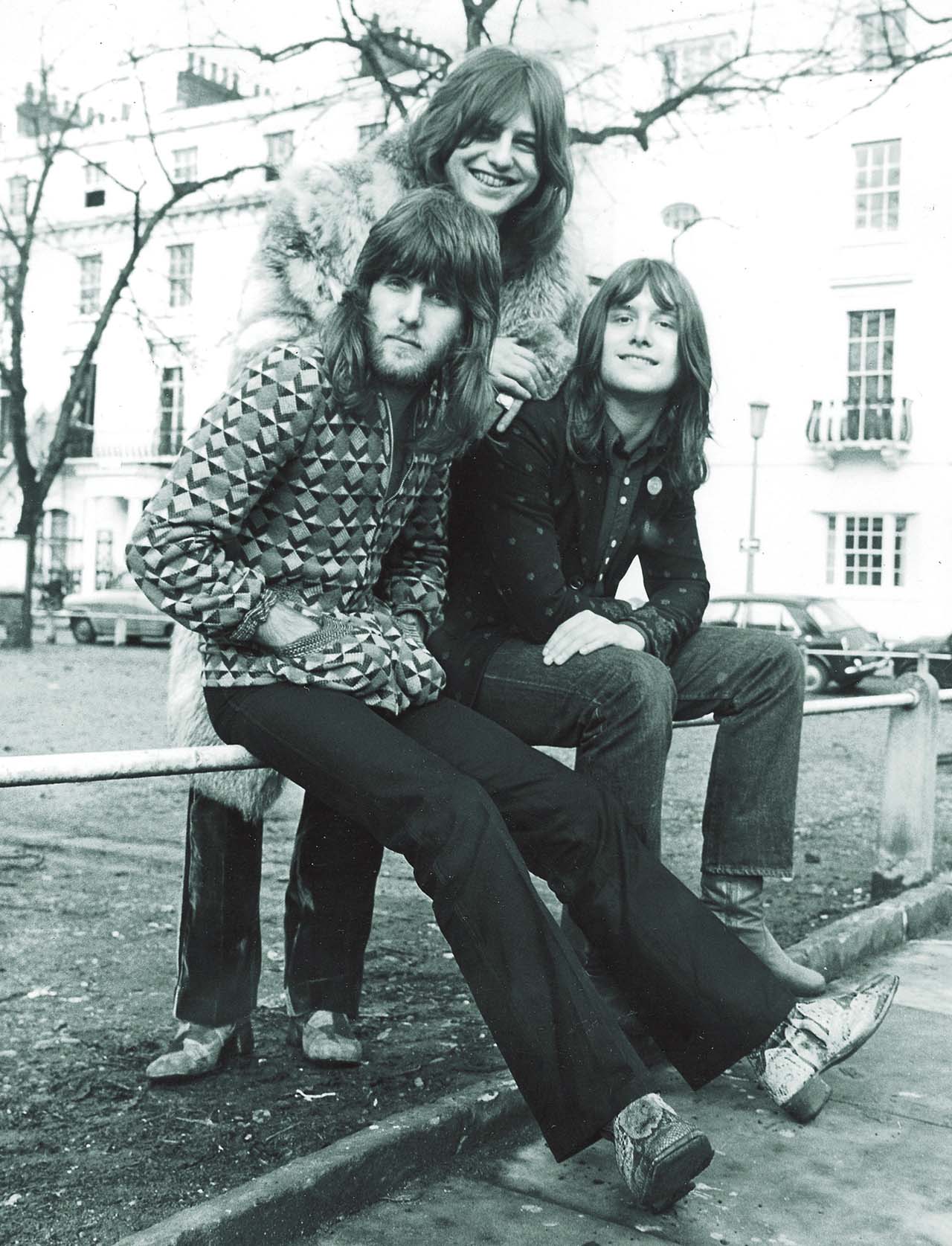

“The first track we did was Tomorrow Night, which was a big hit later on,” Palmer recalls. “But during that period I got the call from Keith Emerson’s manager, Tony Stratton-Smith, who asked if I’d go along for an audition. I said, ‘Well, I’ve got my own band and it’s doing okay…’ but clearly I ended up joining Greg Lake and Keith, which obviously wasn’t such a bad decision!”

Palmer seems ferociously enthusiastic about almost everything in his non-stop, pulse-driven life – but his love and admiration for the music he made with ELP is patently on another level entirely. Happy to embrace their unofficial status as standard-bearers for prog’s greatest excesses, but equally determined to celebrate the overwhelming quality of classic albums like Brain Salad Surgery and Trilogy, he recalls those heady days of world domination with palpable fondness, stating that playing with ELP was “a dream come true, basically.”

“I’d always wanted to play classical music but I didn’t want to play in an orchestra,” he explains. “I didn’t know how to go about it until I bought an album by a French piano player called Jacques Loussier. He used to play in a trio with bass and drums and they’d play Bach in a jazz format. I really enjoyed that. When I met Keith for the first time, he’d already started adapting classical music, but I honestly didn’t think I was going to be in a band with him down the line. Eventually I got the chance to work with him – so ELP fulfilled a musical dream.”

Given the way music and pop culture were evolving in the mid-70s, with disco and punk dominating airwaves and column inches, ELP’s initial, stuttering demise didn’t come as a particularly great shock to the world at large. After 1978’s borderline calamitous Love Beach, the trio went their separate ways, a decision Palmer maintains was the only credible option.

“We never argued about money; we never argued over women or over equipment; we only ever argued about music,” he avows. “But we’d had four unbelievable years and made five really big albums, and there was nothing left, really. It was all over by ’79. When the punk movement came in, we took it badly, like, ‘Oh dear, no one wants us any more!’ We’d never been through the school of hard knocks. We didn’t know what it meant to go out and really have to work hard at it.”

Emerson, Lake & Palmer would, eform twice in the decades that followed their initial flurry of chart-ravaging hugeness. Even diehard fans might struggle to conjure much enthusiasm for 1992’s patchy Black Moon or its even less appealing 1994 follow‑up In The Hot Seat, but that earlier catalogue of groundbreaking brilliance was never likely to be surpassed. Besides which, everyone is allowed to make mistakes, and over 50 years, even Carl Palmer has dropped a clanger or two. Who dares to recall 3 and their 1988 album The Power Of Three or, even more amusingly, Palmer’s first post-ELP project, the undeniably woeful PM?

Radio had become very corporate in America… you’d only hear ELP or Pink Floyd at two in the morning! Asia fell into a space that was ready to go

“Oh, that was absolute rubbish – I’m not going to hide from that one!” he roars, recalling 1980’s wildly misguided 1:PM album. “It was rubbish and I got it wrong. The problem was, I like classical music and I like pop music but it’s a terrible combination to be involved with. I like tunes, I can’t help it. That’s why ELP covered it all for me. We had the classical thing but we also had some really pretty tunes that got radio play. With PM, I went into just playing tunes and it didn’t work. I also broke the rule and ended up playing with all American musicians… and it turns out we do think differently! So yes, that was a complete disaster.”

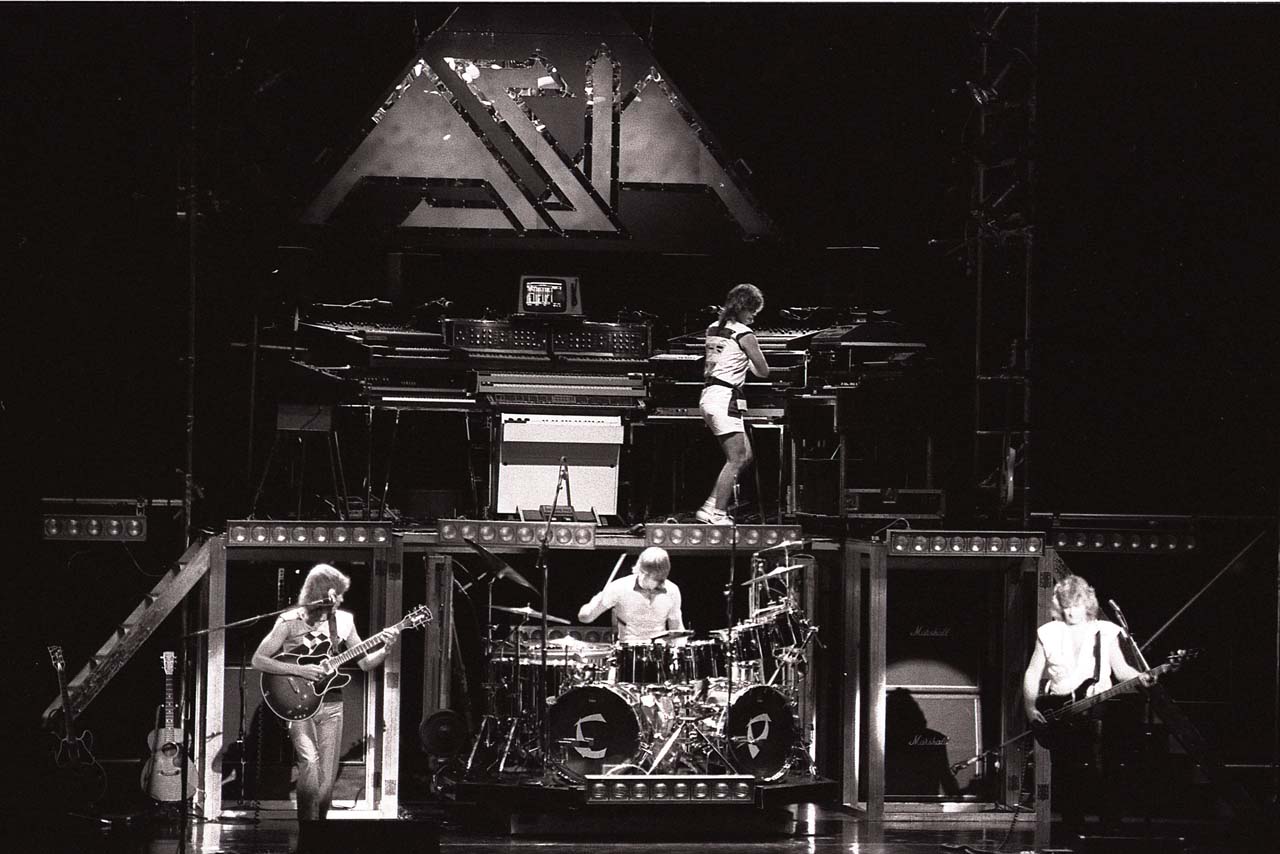

The achievements and sheer bloody‑minded uniqueness of ELP alone would be sufficient – but such is Palmer’s unwavering intensity and remorseless get-up-and-go that he deftly repeated the trick in the 80s, conquering charts all over the world with Asia.

Still clearly affected by the death of John Wetton, he speaks glowingly of the chemistry that sparked into life when he joined forces with his late friend plus guitarist Steve Howe and keyboardist Geoff Downes in 1981. “Yeah, that time it was with English guys and so we had a lot of commercial success! We still had that proggy thing in there but when it came to the tunes, they were so good; and the production was so great, I could really appreciate the beauty of it.

“Radio had become very corporate in America. They wouldn’t play long prog pieces in the daytime, so you’d only hear ELP or Pink Floyd at two in the morning! Asia fell into a space that was ready to go and I’m very proud of it.”

While we’re sauntering along memory lane, it’s a good opportunity to ask about Palmer’s rarely-celebrated collaboration with Mike Oldfield on 1982’s classic Five Miles Out album. One of the more surprising team-ups in prog history (it’s genuinely hard to imagine the quiet and reclusive Oldfield clicking with the verbose and energetic Palmer, but evidently they did), it led to the stunning Mount Teidi, an exquisite meeting of minds named after a volcano on Tenerife, the island the drummer called home for nearly three decades.

“I first spoke to Mike when I was putting together Works I with ELP, and we had a big, long piece called Pirates that I thought he could help with,” he recalls. “But then years later he said, ‘I’ve got something which I think you might like…’ so I went down [to Oldfield’s studio] and there it was – Mount Teidi was born.

“It was just a one-off thing and we never did anything else, but Mike’s a really nice guy. He’s extremely talented. He’s a loner and likes to come out when he wants to. He’s unbelievably professional and a great musician all‑round.”

It might be hard to believe, but Carl Palmer has yet another string to his multifarious bow. He’s been producing extraordinary, eye-frazzling artworks using drumsticks equipped with LED lights; it’s an endearingly eccentric sideline, and yet another way for Palmer to indulge his obsession with music and its limitless possibilities.

“It all started in ’73 when I started taping little light bulbs to the end of the drumsticks, with a little wire that ran down to a battery on the floor,” he says. “I got a photographer friend of mine to take pictures of me miming playing the drums, because you’d get all these flashes and arcs and shadows. He took some pictures and one of them ended up in the Birmingham Mail, and it was a fantastic picture. Roll forward about 30 years, they started to develop drumsticks where the tip was a little LED light, but every time I got a pair, they broke. They weren’t very durable. Roll forward another 10 years and they invented some that were durable. You couldn’t break them, the lights never went out and they were self-generating.

What’s helped me is playing with younger musicians. They’re so dedicated… It makes me cry sometimes, it’s so fantastic

“You can create some incredible canvases. So I teamed up with the guys at a company called SceneFour and I’ve had two art books out. We’ve sold a lot of artwork and I’ve raised over 30,000 dollars for charity so far.”

The most recent series of canvases that Palmer has created are a trio of tributes to Keith Emerson, Greg Lake and John Wetton, titled Welcome Back, Lucky Man and Heat Of The Moment respectively. It’s not, as he admits, a project he had ever wished to pursue, but it’s a great way to pay his respects to such esteemed colleagues.

Meanwhile, the music of ELP is alive and well and being belted out with some force by Palmer and his current henchmen, guitarist Paul Bielatowicz and bassist Simon Fitzpatrick, as Carl Palmer’s ELP Legacy. As the only surviving member of the prog titans, he plainly feels a responsibility to breathe fresh life into the challenging and ambitious music that first made him a star.

“I’ve had my band since about 2009. Paul and Simon are both phenomenal players,” he says. “It’s instrumental prog rock with a kind of metal edge. You’ll either like it or you won’t. I think I’m more a delicatessen than a supermarket these days. I understand there’s only a certain amount of people that are going to enjoy what I do, but the ones who do enjoy it really love it, and that’s what it’s all about.

“What’s helped me is playing with younger musicians. They’re so dedicated to being the best they can be at their craft. It makes me cry sometimes, it’s so fantastic. That keeps me on top of my game.”

More than 50 years after first earning a crust with sticks in hand, Palmer remains an unstoppable force of nature. He ends our conversation by noting that, somewhat against the odds, the near-septuagenarian is still improving as a drummer; and as a result he’s enjoying himself more than ever.

“My philosophy is as simple as this: if I can improve, I’m gonna carry on playing and working,” he explains. “This is what I love to do and I’ve never had a proper job, if you know what I mean.

“If I can’t improve but I can maintain a standard, I’m gonna carry on. But if I can’t maintain the standard and I’m not improving, I’m gonna be gone and you’ll never get another interview from me again, because I’ll be out. I haven’t reached the stage yet where I’m just maintaining a standard, so I’m very happy. I think I’ve got another 10 years in me!”

Dom Lawson has been writing for Metal Hammer and Prog for over 14 years and is extremely fond of heavy metal, progressive rock, coffee and snooker. He also contributes to The Guardian, Classic Rock, Bravewords and Blabbermouth and has previously written for Kerrang! magazine in the mid-2000s.