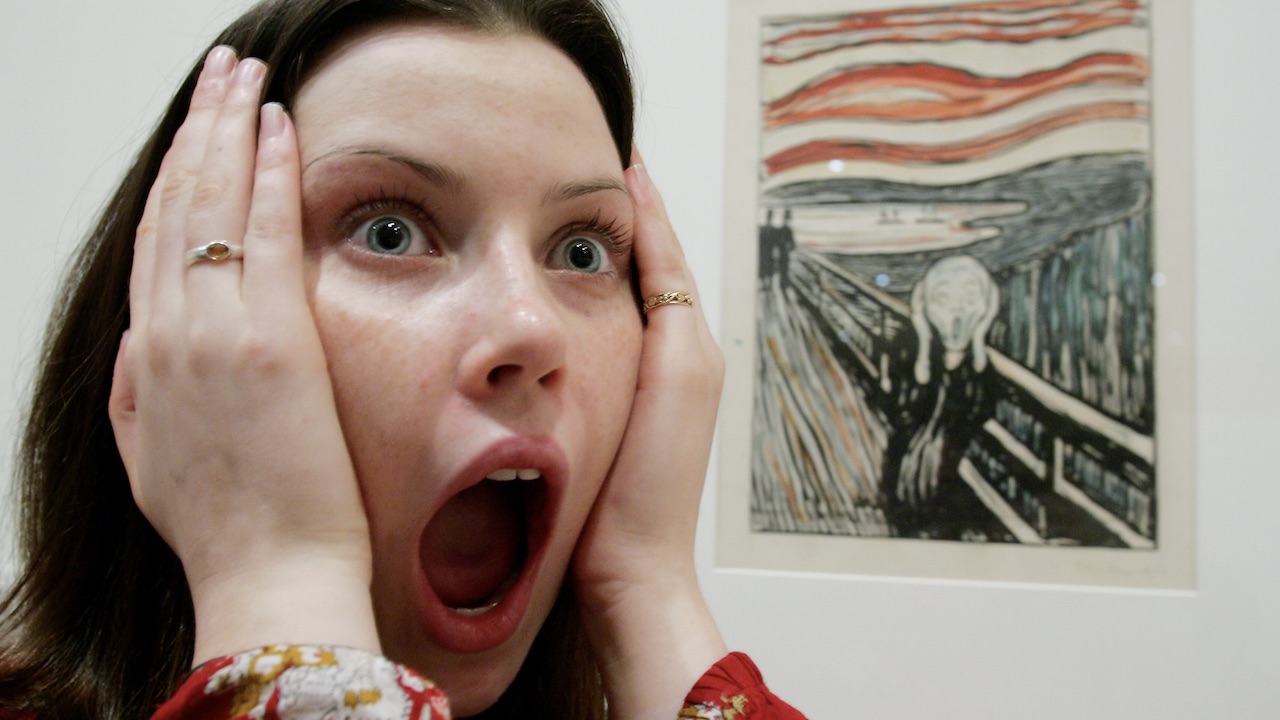

Chaos, cash and Caligulan excess: How Emerson, Lake & Palmer made Brain Salad Surgery

In 1973, prog-rock behemoth Emerson Lake & Palmer unleashed their ultimate album: Brain Salad Surgery, the record that marked the pinnacle of their creative extravagance

On the face of it, a band like Oasis might appear to have been pretty bloody enormous: their phizogs regularly leered from the tabloids; they headlined Glastonbury; the members probably boast more gold discs than there are Burberry caps in Burnage. But by comparison to the Emerson Lake & Palmer of 1973, Oasis were but an insignificant microbe.

For ELP were huge, their every gesture enormous, their deliciously overblown muse utterly titanic and, my God, were we impressed?

Even the ever-cynical bubble-popping hacks of the NME saw their prose grow ever more purple as they snatched desperately for the requisite adjectives to describe just how ‘not worthy’ we all were. Carrying an Emerson Lake & Palmer album under your arm became the schoolboy equivalent of Mensa membership; it screamed to all who gazed upon you that: ‘He gets this: ergo he is old enough to shave, regularly does it with girls and would sooner miss Monty Python’s Flying Circus than soil his Brut-splashed ears with a single smidgen of Slade.’

Here, then, was true sophistication, a vinyl passage-to-manhood in a cardboard sleeve. Aborigines went on walkabout; we listened to Tarkus.

To make the quantum jump from the pedestrian pop of the musical mainstream to the progressive pomp of ELP was to embark on a truly head-spinning expansion of one’s musical perspective. While Marc Bolan’s T.Rex were firmly rooted in lisping Eddie Cochran three-chord traditionalism, ELP had long since abandoned the constraints of the stultifying three-minute form. By introducing both classical and jazz elements to cutting-edge rock technology, ELP appeared to be nothing less than larger-than-life progenitors of a giant evolutionary leap forward; Nietzschean supermen in ill-fitting armadillo suits.

One day, we mused, all bands will be as unapologetically enormous as this. But, with our awe-stricken pre-punk appetites whetted for the unfeasibly massive, we craved something even more gargantuan from our three heroes, and like all true thrill-seekers were compelled to push the envelope yet further.

We wanted the hugest, most ear-boggling sounds from the furthest technological frontier available to modern man; we wanted the fastest and most intricate keyboard runs and percussive paradiddlings audible to the human ear; we wanted lyrics that we couldn’t possibly understand; and, most importantly of all, we wanted them in morbidly obese half-hour slabs. Ultimately, we wanted Brain Salad Surgery.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

So how did Emerson Lake & Palmer become ELP, and why were they allowed to spend so much money?

Keith Emerson’s father played piano competently enough by ear, but when his young son started to mimic his decidedly amateur ivory-tinkling he insisted upon paying for some expert tuition for the boy. Lessons with Mrs Smith were “really boring to begin with”, but the benefits of his new-found skill soon began to pay dividends: “I became popular at school,” remembered Keith, “and avoided a lot of bullying simply by playing all the rock’n’roll tunes of the day.”

After making his first public appearance at the local rifle-club dinner and dance (“I avoided getting shot at”), Emerson set about honing his own style: “I wasn’t into the genre of the day – The Beatles, Stones and Yardbirds – I fancied myself more as a jazz player. Then I got more into blues and – after hearing guys like Brother Jack McDuff – the Hammond organ.”

In late summer 1965, Emerson joined established Brighton-based R&B group, Gary Farr & The T-Bones: “I found playing with them acceptable because Gary Farr, who was a pretty good blues singer, had jammed with Sonny Boy Williamson and when T-Bone Walker came over to play the clubs we’d back him.”

Following a brief spell with Island Records’ first non-Jamaican recording artists, The VIPs, Emerson formed The Nice, a band that rapidly developed a flamboyant style of virtuoso cross-generic experimentation, but started life as the relatively anonymous sidemen to PP Arnold: a former Ike & Tina Turner Ikette, hand-picked for stardom by Mick Jagger and summarily signed to Andrew Oldham’s Immediate label.

“[Nice bassist] Lee Jackson was a late addition to the T-Bones,” Keith recalled, “and we’d often jam backstage at gigs. I’d play some Brubeck or Bach, whatever came into my head, and Lee would say: ‘We should do this at some point.’ We couldn’t do it with the T-Bones but the opportunity arose to do something new when I was invited by PP Arnold to put a band together in support of her single version of ‘The First Cut Is The Deepest’.”

Prior to Arnold hitting the stage to belt out gutsy reinterpretations of contemporary Stax classics, The Nice used their nightly half-hour warm-up stints to excellent effect, gradually shaping a stunning repertoire of pioneering progressive fusion that soon set them apart. Encouraged by a slew of positive media feedback, the band elected to go it alone with keyboard wunderkind Emerson as their focal point.

While preening like a priapic peacock presents no problem whatsoever for a guitarist, thrusting several hundredweight of keyboard into your crotch is a logistic nightmare; consequently Keith found other ways to dazzle audiences. Burning the American flag on the stage of the Albert Hall while vociferously contemporising selections from Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story was one memorable device, but it was the Nazi cutlery that truly boggled the proto-prog mindset.

“I just got fed up of everybody else getting the limelight,” said Emerson of the birth of his showmanship. “I’d have loved to have been a guitarist because they could move around with the instrument, but then I saw this keyboard player at the Marquee called Don Shinn. He had problems with his Hammond organ – certain tabs on the top of the keyboard had fallen off – so he used a screwdriver to change the tabs. And then, quite accidentally, the back of his organ fell off.

"I’m sure it wasn’t intentional, most of the audience were chuckling and Don was all, ‘Oh God, my instrument’s falling apart’, but I was enthralled. “I thought: ‘I can use this, but instead of a screwdriver I’ll use a Turkish dagger with a curved blade.’ But our road manager at the time was Lemmy – latterly of Motörhead and an avid collector of World War II memorabilia – who said, ‘’Ere mate, if you’re gonna use a knife, use a proper one’, and he gave me a Hitler Youth dagger.”

And the rest, as they say, is history.

“I grew up in a prefab,” admitted Greg Lake over an agreeably chilled glass of Chablis. “Didn’t have a pot to piss in. Then I started to play guitar and realised I could actually earn money.”

As humble Bournemouth beginnings gave way to never-had-it-so-good adolescence, 12-year old Greg picked up his six-stringed passport out of provincial poverty and almost immediately formed Unit Four with a trio of like-minded school chums.

“I loved the guitar,” smiled Lake, his reminiscences still characterised by the slightest suggestion of a lilting Dorset burr. “I loved playing, not only was it an open door to a career, there was also this mass adoration thing. It was the early days of The Beatles so it became the fashion to scream; I remember distinctly coming out of gigs and the van would be completely covered in lipstick. So it seemed like a good way to go.”

Following a couple of years spent gravitating through the ranks of The Time Checks and The Shame (working through an apprenticeship on the south coast circuit playing the contemporary chart hits), Greg ultimately relocated to London to join future Uriah Heep members Lee Kerslake and Ken Hensley in The Gods. Heavy duty gig rotation earned the band a deal with EMI, but on the eve of their first recording date The Gods fell apart.

“I can’t remember what happened,” Greg shrugged expansively (despite the fact that it’s often been reported that it was he who initially walked). “Something sordid, no doubt.”

Meanwhile, one of Greg’s oldest friends was similarly floundering in Swinging London’s never-more-cutthroat musical morass.

“When we were boys,” said Lake, “Robert Fripp and I went to the same guitar teacher – a guy called Don Strike – and used to play duets together. Robert would come along and watch me before he was in a band, but he eventually formed a very strange outfit called Giles, Giles & Fripp. They’d made this album for Decca called The Insanity Of Giles, Giles & Fripp – a very peculiar record with a tasteless cover – and Decca said to them, ‘If you don’t start making commercial, sensible records, we’re going to drop you’.

"So Robert said to them, ‘What do you mean?’ And they said, ‘You haven’t even got a lead singer’. So Robert gave me the call and said, ‘Hello, my dear’ in his West Country accent. ‘Would you be interested in being the lead singer for the band?’ he asked, and I said, ‘Yeah’ – because they had a record deal, which was fantastic. But then he said, ‘The only thing is, we don’t need two guitarists. Will you play bass?’ So that’s how that started.”

The Lake-augmented combo were re-named King Crimson and the rest, as they very probably don’t say, is history of a marginally less knife-toting nature.

You soon learned not to ask Carl Palmer if he started out by banging wooden spoons on saucepan lids. “My grandfather was a Professor of Music at the Royal Academy,” he countered. “My father played piano and I had the opportunity to start on piano, violin, cello or piano-accordion. I chose violin, but after a brief period, looking in a music shop window and hearing some records, I moved over to drums. I had a teacher from the Birmingham School of Music from the age of eleven, so I didn’t have any pots or pans as you put it.”

Quite.

Anyway, after sporting the red uniform jacket of the, then popular, palais orchestra (a 16-piece dance band, basically) from the age of 13, the prodigious percussionist decided – with the help of his musically inclined family – to investigate pastures new: “During my last year of school we decided that, because my reading was up to scratch in pretty much all forms of music, it would be a good idea to look into contemporary music.”

Upon answering a classified advertisement in The Birmingham Mail, young Carl found himself auditioning for local R&B chancers The King Bees at the Plaza Ballroom, Handsworth, conveniently situated at the top of his road.

“I expected them to give me music and they didn’t,” remembered Palmer, “They gave me a bunch of forty-fives and said, ‘Learn those and come back tomorrow’. I thought that was kind of bizarre, so I dashed home, charted them out immediately and couldn’t believe how easy they were.”

Unsurprisingly, Carl Palmer was a King Bee before the day was out. Eight months of gruelling all-nighters later and the tireless 16-year old caught the eye of Chris Farlowe who offered him a job on the spot. Carl’s transition from moonlighting Black Country schoolkid to scene-making London circuit pro was nothing if not swift: “I left school on the Friday, left home on the Sunday, did the audition on the Wednesday and was working in Chris Farlowe’s Thunderbirds by the following weekend.”

It was an exciting time, certainly, but Palmer remained uncommonly astute, and set about securing all the extracurricular session work he could find. Tireless networking paid off when star management team Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp called Carl in to record sessions with The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown, for when the band’s original drummer Drachen Theaker bailed for “some kind of religious sect” midway through an hallucinogen-fuelled American jaunt, it was Palmer who leapt into the breach.

The Crazy World were riding high after their hit single, Fire, but as the band endeavoured to snort Haight-Asbury whole, the drug experience began to take its toll and after a few months of sustained psychedelic fame Arthur disappeared and Carl formed Nice-styled, super-heavy power trio Atomic Rooster with keyboard player Vincent Crane.

Despite all outward appearances, all was not quite as well as it might have seemed with The Nice, King Crimson and Atomic Rooster by the spring of 1970. All three were staggering to an inevitable halt, leaving their main protagonists in dire need of some real musical challenges and consequent progression.

First of all, Keith Emerson had detected a change in the musical zeitgeist that The Nice were utterly incapable of adjusting to. “The trend in music was toward tunes and melodies,” said Keith, “and while Lee [Jackson, The Nice’s bass player and vocalist] did a fair enough job, he had a very gravelly Geordie accent. Then I happened to hear King Crimson.”

King Crimson, featuring the quintessentially English, choirboy clarity of Greg Lake’s vocals, had supported The Nice on a number of previous occasions but it wasn’t until this crucial juncture that Emerson really started to take notice of their singer’s not insubstantial melodic potential. And, when he was informed that not only could Lake double up on bass but also played guitar, he engineered an on-stage jam between the two at Bill Graham’s Fillmore West.

The pair then pursued what Keith remembers as “a very furtive relationship”, while Greg decided what to do about King Crimson. He wouldn’t have to consider long, for King Crimson were about to disintegrate before his very eyes; both sax player Ian McDonald and drummer Michael Giles were tired of the road and elected to leave simultaneously.

Now, offered the choice between remaining with Robert Fripp or accepting a fresh challenge with Keith Emerson, Lake ultimately opted for the latter. You’re probably comfortably ahead of me here, and primed for the inevitable arrival of pot-free zone Carl Palmer in the soon-to-be-revolving drum stool, but hang fire, for things could have been very different indeed in Keith Emerson’s Nice Nouveau.

“I had several choices before Greg,” revealed Keith, “My first choice was Chris Squire, who said, ‘I don’t regard myself as a lead singer, but I’m okay on harmonies’. Then I decided to seek out Jack Bruce, who was charming but said, ‘It’ll be my band, and you’ll play what I write’. So I said, ‘Thanks, but no thanks’.”

And so to one of rock’s great enduring rumours/urban myths, the much speculated-upon involvement of Jimi Hendrix in an embryonic ELP that, some still insist, very nearly resulted in that most fated of all acronyms, HELP. Well, they were toying with the notion of HELM until Jimi’s fatal trachea/tuna fish sandwich interface, but that’s about the best we can offer you.

“I had a meeting with Mitch Mitchell a little over a week before Jimi died,” claimed Greg, “and Jimi had formed the Band Of Gypsies, which was alright, but it wasn’t going anywhere, and Mitch said, ‘I think Jimi would like to do something else, what about getting together for a jam with him?’”

“I did jam with Hendrix,” Keith revealed, “but, quite honestly he was his own person, who had his own ideas and direction he wanted to go in, and I didn’t see how I could possibly complement what he was doing, or what he was trying to do. Maybe if he’d turned down a bit, who knows? I was very worried about guitar players because they always cranked it to eleven, but out of all guitar player possibilities I would have gone with Steve Howe, but Steve was with a band called Tomorrow and was contemplating Yes.”

So there you go, romantics claim it was only Hendrix’s premature death that precluded him from throwing in his lot with Emerson Lake & Mitchell; even Lake himself remembered it as, “Jimi died and simultaneously Carl came on the scene”. But of course ELP made their big-league debut at the 1970 Isle Of Wight festival, an event at which Hendrix was still very much alive… and indeed playing with Mitch Mitchell.

So how did Palmer snatch the very stool from beneath the Mitchell cheeks?

“It was Greg’s decision not to use Mitch,” Emerson insisted, “even though I’d known Mitch since he’d played with Georgie Fame & The Blue Flames and respected him as a great technical drummer. He had that jazz influence that I had too. If I mentioned Miles Davis or John Coltrane to Mitch I knew he’d understand, whereas Greg would be going, ‘Nah, Simon & Garfunkel’.

“Greg really didn’t like jazz although he struck out at it sometimes just to appease me, I suppose.”

Greg didn’t like jazz, surely some mistake?

“You look at jazz players and they all sound the same,” Lake would cheerfully enthuse when offered the very least encouragement, “with that dull bass tone and those glissy runs. It’s all very well, but it’s like lounge music by and large, and that’s the trouble with jazz generally. I’ll tell you a thing about jazz: I don’t find a lot of emotion in it. There is a lot of musical commentary, but not much emotion, and as a singer I always look for passion, and so jazz is very incidental.”

So no, it seems that Greg didn’t like jazz much after all.

But meanwhile, back in 1970: “We played once with Carl,” said Greg, “and there was a chemistry that clicked. He was so energetic and enthusiastic.”

“He was our only real choice at that time,” Keith shrugged. “If Carl hadn’t arrived when he did I would have gone looking for an American drummer.”

“I was only ever interested in playing in a three-piece group,” Palmer recalled, “but when Keith asked me if I was interested I was apprehensive because Atomic Rooster were doing incredibly well and I’d just bought a Mercedes van. I knew of The Nice, obviously, but I didn’t know who Greg Lake was. I knew of King Crimson but I didn’t know he was the singer, so I was a bit apprehensive.

"Anyway, after playing with them a couple of times I realised that everybody was going to have their say in what went on, on the financial front there was an agreement struck with Atlantic Records that I couldn’t refuse, the musicians were better than in Atomic Rooster and it looked like it offered more of a chance to succeed on a global level. So I took the chance and jumped ship.”

And what a fortuitous jump it turned out to be.

Save to say, Emerson Lake & Palmer went on to sell unfeasible quantities of records over the course of the next three years, and while the apoplectic rock’n’roll intelligentsia – as exemplified by an outraged John Peel harrumph-ing self-righteously about a “waste of talent and electricity” upon witnessing their Isle Of Wight debut – spluttered their abject disapproval, the gentlemen of ELP merely laughed themselves in an invariably bank-wards direction and improvised on Bartók like men possessed.

But with three indomitable virtuosos in a single band there was always an enormous potential for healthy creative competition to descend into bitter temperamental spats.

“We were three competitive individuals,” said Emerson diplomatically, “but I don’t think it was really a question of trying to outdo each other. I do remember when we played the Lyceum in late nineteen-seventy or seventy one and we had a power cut. There was an acoustic piano on stage so I went up to Greg and whispered, ‘Why don’t I just play the piano for five or ten minutes?’ And he said, ‘No, we’ve all got to get offstage, all of us’. That was a bit weird… I wouldn’t do that now, believe me, ‘I’d say fuck you, I’m fucking playing the piano’.”

“In a band you’ve got to have egos,” explains Greg, “because that’s what makes people want to shine. If you have people who don’t care, the whole thing becomes wishy-washy. When people care, they get opinionated – and even that’s okay. But what really is a problem is when you put that volatile combination into a Lear jet for six years. I defy you to name one major band that hasn’t got those internal pressures and conflicts. By and large, musicians aren’t normal, balanced individuals, they’re highly charged and that was the case with ELP.”

Meanwhile, the band’s on stage communication bordered on extrasensory perception: “We improved to the extent where we knew what the other was thinking,” said Keith. “We could actually play without eye contact, I hazard to mention ESP, but it was very tight. It was productive, but extremely exhausting, even to the extent where we had individual limos. We didn’t socialise together because we were so drained from communicating musically. As we’d already communicated on stage there was really no reason for us to have a meal together; the three of us would just sit there in a blank stupor."

To the outsider, if there was one member of ELP who had more reason than most to feel unfulfilled and under-employed, it was Greg Lake. During the extensive head-to-head cutting contests between Emerson and Palmer, Lake’s role was often reduced to that of Noel Redding-styled ballast. And while a decision was made to eschew the populist allure of the UK single charts by refusing to release such commercial ballads as Lucky Man, Take A Pebble and Still… You Turn Me On, these were Lake’s most visible contributions to the band.

One even suspects that Lake could have been an even bigger star without Emerson and Palmer, a proposition seemingly proven by the gargantuan success enjoyed by his evergreen ’75 solo adventure I Believe In Father Christmas. But Greg, it seems, was quite content with his lot. “I had every chance to do what I wanted in the band,” he insisted with the full benefit of hindsight.

“I produced the records, so had no real reason to feel constrained. I probably could have developed a career as an acoustic guitar James Taylor-ish kind of guy, but I’m too rock’n’roll for that. I enjoy high-energy music, so I should never be mistaken for some sort of placid minstrel. It’s just one of the things I do, and while I love the acoustic guitar, I wouldn’t want a career of that. I’d fucking fall asleep.”

We used to take quite a lot of drugs. We found Carl and we thought he was dead. We went to his room and he was lying on his bed covered in vomit…

Greg Lake

And as for singles: “We set out to make music that was conceptual and – in the nicest possible way – bigger than singles. It wasn’t about being grandiose; it was just a different way of performing.”

But Greg’s wasn't entirely satisfied: “One thing I do regret is that ELP didn’t encompass music that had black influence, and I think it would have benefited a lot from that. To have more soul: it was too British, too clinical and very European and I think it would have been even better with that element in the mix. But you can’t have everything, I just feel grateful that it was what it was, because it is hard enough to be anything.”

Coming up to the recording of Brain Salad Surgery, Emerson Lake & Palmer seemed unassailable. They’d been voted, both collectively and individually, to the very top of every readers’ poll extant and had just set up their own Manticore label which ostensibly gave them greater artistic freedom than ever before. But were the band as confident as one might expect?

“We’d had a long lay-off,” Keith Emerson recalled, “and were really unsure of what direction we should go in. All our previous stuff had gone gold, which we were very thrilled about, and we simply wanted to augment upon that. But it took me a long time because I never like to jam around and play indiscriminately whatever it is that comes into my head. But I do remember arriving at Advision Studios with this fugue design, Greg learning the notes and it being a pretty painless procedure.

"We were all inspired and one thing would lead to another. We’d all contribute and that’s what a band should be. Whether or not you regard yourself as a composer, it doesn’t really happen unless everybody else involved enjoys playing what you’ve written.”

“We quickly learned that whatever you put on a record you’d have to play live,” added Greg, “So we started preparing the records in the same way that you’d prepare a tour. Brain Salad Surgery was made by rehearsing live in a cinema. We bought a cinema – now that was an indulgence – and rehearsed it in there until we got it in a state where we thought it was good. Then we took it to the studio for an upgrade, but would essentially record live – which was one of Keith’s great abilities. That way, when we finally took it back on to the stage we knew how to play it.”

“It was recorded at a time when the band felt incredibly warm to each other,” said Carl, “and, while I think it marks the height of ELP’s creative powers, it came very quickly. I can’t remember having to labour over much of it, and I don’t think it took more than six weeks to make.

"I just remember it as being a very lovable period really. Just so experimental; I was laying cymbals on the floor for overdubs to get a different sound, and we were putting keyboards into different rooms, putting a microphone into the street to get ambient noise and it was just fantastic. It was one of those things that just happened and you wish would happen every time you go into the studio.”

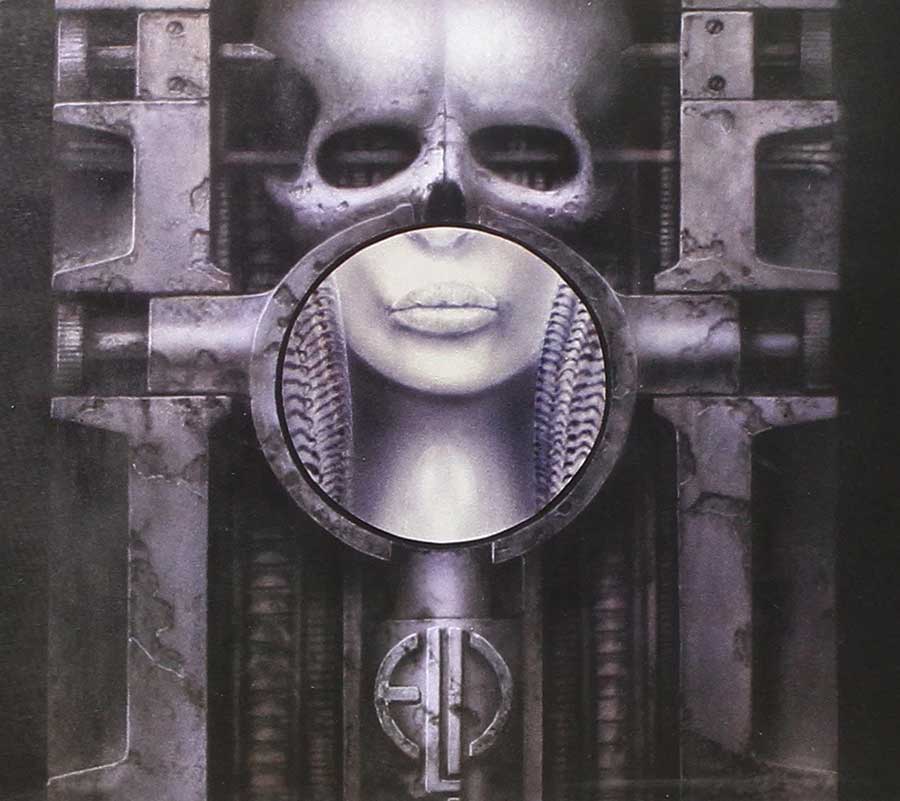

Other weapons in the Brain Salad Surgery armoury included extra lyrics from Pete Sinfield (Greg Lake: “I worked with him in King Crimson and while I’m not a bad lyricist, Pete’s better”), stunning cover art from the then relatively unknown HR ‘Alien’ Giger (the original featured a fearsome phallus that had to be craftily excised) and a thinly veiled titular reference to good old oral sex.

“The working title was Whip Some Skull On Ya,” expounded Keith, “until our tour manager pointed out a Dr John lyric that features the line ‘give me some Brain Salad Surgery’ which, in the vernacular, means the same as Whip Some Skull On Ya: a blow-job, basically.”

Ah yes, what better cue for tales of Caligulan excess from the Emerson Lake & Palmer tour diaries? Well yes, they did indeed tour tirelessly (not least in support of Brain Salad Surgery) and with their own proscenium arch, as well as every kind of revolving instrument that you ever thought possible, including some that you hadn’t, like a grand piano that flipped end-over-end while a strapped-in Emerson hammered manfully at the ivories like an unholy cross between Arthur Rubinstein and Biggles. But according to an ostensibly impenetrable party line the trio were usually far too pooped from on stage improvisation to reach for the proverbial mud shark.

“Most of your day was spent doing the normal mundane things that everyone does,” Greg insisted. “The only moment that’s really great is when you play. And you even develop an immunity to walking out in front of twenty thousand screaming people when you do it every night. We were never a band who used to throw TVs out of the windows, it simply wasn’t like that. So really I’d have to say no, it wasn’t that crazy.”

Didn’t the hot-and-cold running groupies help you deal with the humdrum?

“You realise quickly is it’s not you that they want,” sighed Greg. “It’s what they think you are, it’s what they see, the image. And if you’ve got half a brain you see that, and you understand that, and it ceases to become an ego stroke.”

Phew, so that just leaves drugs then…

“In the early days we used to take quite a lot of drugs,” admits Greg, “but it stopped one day when we found Carl and thought he was dead. We went to his room and he was lying on his bed covered in vomit. We thought he was dead, but as you know, he wasn’t. But that was it. It finished us off as far as that went.”

And then, as if to add insult to injury, along came punk rock in a cloud of year-zero invective, causing ELP to flee for the Americas and watch their formerly gilt-edged stock gradually fall into prematurely enforced decline. So was 1979 the right time to split?

“Yeah, I think so,” said Keith, “because I’d basically exhausted that idea and I was fed up with presenting music I’d spent a lot of time on to receive a lackadaisical response from the other two. By that time I’d been playing with a lot of professional musicians; musicians that could read, musicians that could write, and for me to sit down and write a manuscript, then take it into the studio and have professionals not argue or say, ‘I don’t want to play that’ was just fantastic. So, for me, it was a case of, ‘I just don’t need this any more’.”

“It was an inevitability,” Greg shrugged. “We had just played too many shows to make too many records in too short a space of time. That was the principal problem. It’s never a good time to bring something to a close, but I think that it was a better option than going on. The Love Beach album was a bridge too far.”

“We’d been working continuously for an eight-year period,” concluded Carl, “We’d recorded an album nearly ever year and done countless global tours. There was really nothing left to do."

The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 70.

Classic Rock’s Reviews Editor for the last 20 years, Ian stapled his first fanzine in 1977. Since misspending his youth by way of ‘research’ his work has also appeared in such publications as Metal Hammer, Prog, NME, Uncut, Kerrang!, VOX, The Face, The Guardian, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Electronic Sound, Record Collector and across the internet. Permanently buried under mountains of recorded media, ears ringing from a lifetime of gigs, he enjoys nothing more than recreationally throttling a guitar and following a baptism of punk fire has played in bands for 45 years, releasing recordings via Esoteric Antenna and Cleopatra Records.