Charlie Watts is rearranging chairs around a strategically placed TV screen of titanic proportions. I’ve been summoned to The Hospital Club in London to discuss his latest project, The ABC & D Of Boogie, which finds the drummer, along with childhood friend and bassist Dave Green, teamed up with a pair of the world’s leading boogie woogie pianists: German veteran Axel Zwingenberger, and the prodigious Ben Waters.

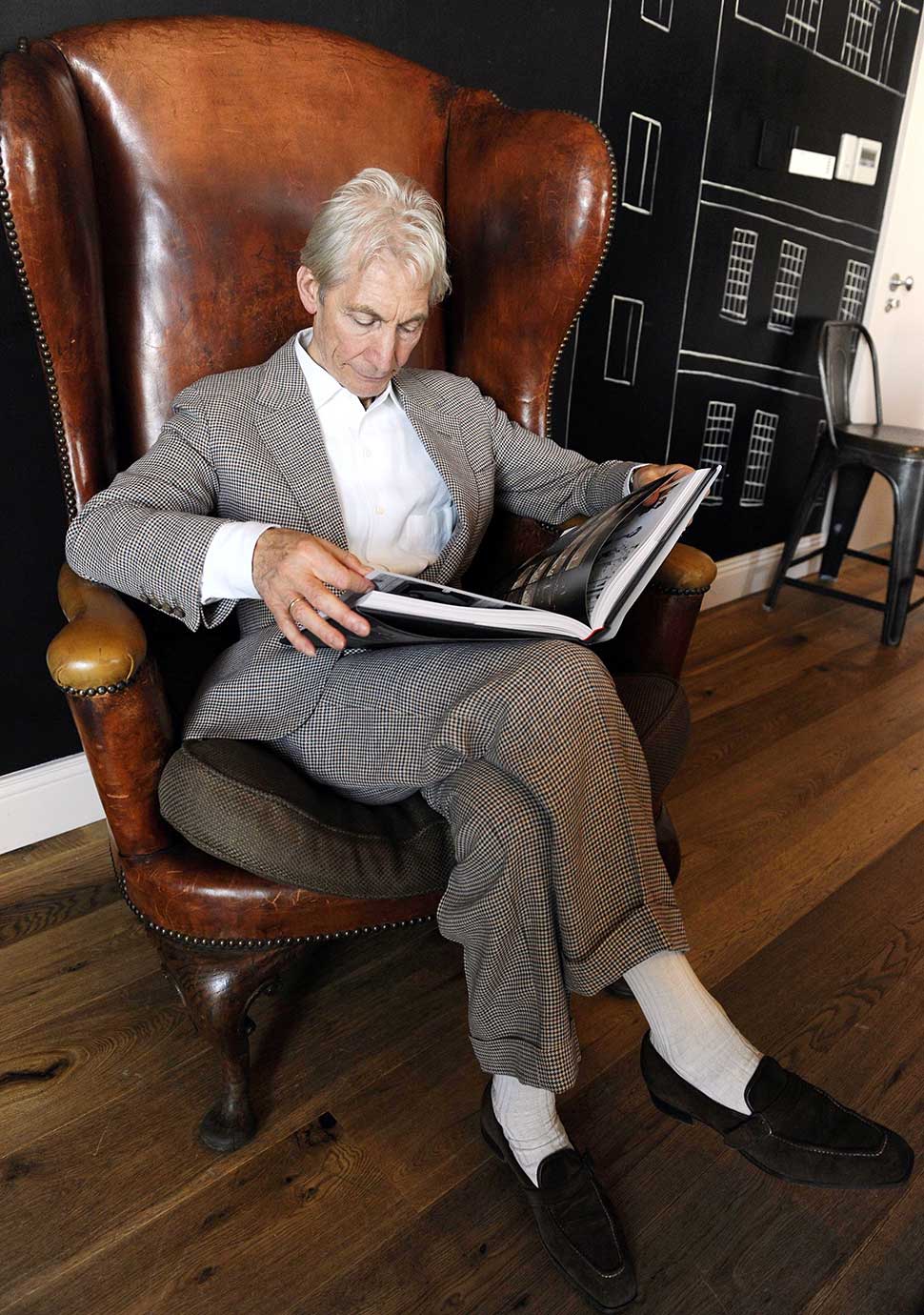

With furniture arranged to our host’s satisfaction, we start by discussing Rolling Stones: 50, the weighty, band-curated, career-wide compendium of compelling photography that sits on the table before us. Oh yeah, Charlie’s also in the Rolling Stones, but he doesn’t like to talk about it.

For Charlie, the heady days of touring in the 60s pale into insignificance compared to the unfolding events at Nottingham’s Trent Bridge. The Test match playing out over my right shoulder explains exactly why he took great pains in personally rearranging the furniture before commencing our chinwag.

Looking at the book, did it strike you how fortunate you’ve been to have your life documented so closely?

I’d never thought of that. I’ve never seen half of them things. It was a revelation, because you never see half the stuff.

In a way it’s kind of a shame that as the book progresses, there’s less and less candid stuff. It gives the impression that for the last three decades, the band haven’t spent too much time together other than on stage.

As you reach the end, the tours are two years long. So I’m living with Ronnie Wood for two years, so I don’t need to see him for another two years. In the early days, the tours went from one to the other… Oh shit, he’s out [the cricket on the muted television behind me has grabbed Charlie’s attention]… Er… Er… Where was I up to?

You were talking about touring.

In the mid-60s the tours would be a trip around England, then a trip around America, recording in America, back to Europe, England to America. You were living together the whole time, and we used to get a month off, at the most. You were younger, though. And also you were more photogenic, to be honest [laughs]. I don’t think Keith would want you photographing him at two in the morning now.

Brian Jones was the first Stone you met. Did it feel like you were joining his band?

It was his band, really. He was the one with the passion. Brian also played slide and steel, things that people didn’t play. He’d play like Elmore James. We used to go to dances and he’d be playing [James’s] Dust My Broom. Nobody’d heard of this stuff.

Do you think Brian would have been happy just to keep it like that – a purist R&B band?

No. One of the things that fucked Brian up was wanting, and desperately trying, to be a star. He was a star, but he couldn’t cope with it, physically or mentally.

How did you feel when Sam Cutler started introducing you as ‘The Greatest Rock ’N’ Roll Band In The World’ in 1969?

I didn’t believe it. What about Little Richard? Then you have Dave Bartholomew and Fats Domino, Chuck Berry’s studio band - there isn’t a better rock ’n’ roll band. That’s where we got it from. Roll Over Beethoven by everybody else is a joke. We came close sometimes with Little Queenie or Around And Around.

Maybe you’re better than you thought.

I can’t hear them like you, so I don’t listen to them. A lot of white bands to me are vastly overrated. I say white bands because most of the music I love to play on record is by black American musicians, 40s and 50s stuff. When white musicians did get hold of the blues, they seemed compelled to expand it in all directions: Led Zeppelin, Cream, 15-minute versions of Crossroads. The Stones never did. Zeppelin were amazing. Just the sound of Bonham and Jimmy Page was an amazing sound in itself, without anything else. And then you had the fact that they were bloody good players.

Did you read Keith’s book?

No. I don’t have to. I know him. He very kindly sent me a signed copy because I love signed books – I collect them – but that was it for me.

Have you considered doing a similar one yourself?

No. I wouldn’t know what to say. I’m very private. I wouldn’t want to talk about half the things, and I forget a lot. I’m not really that interested in talking about me… me and the Rolling Stones, actually.

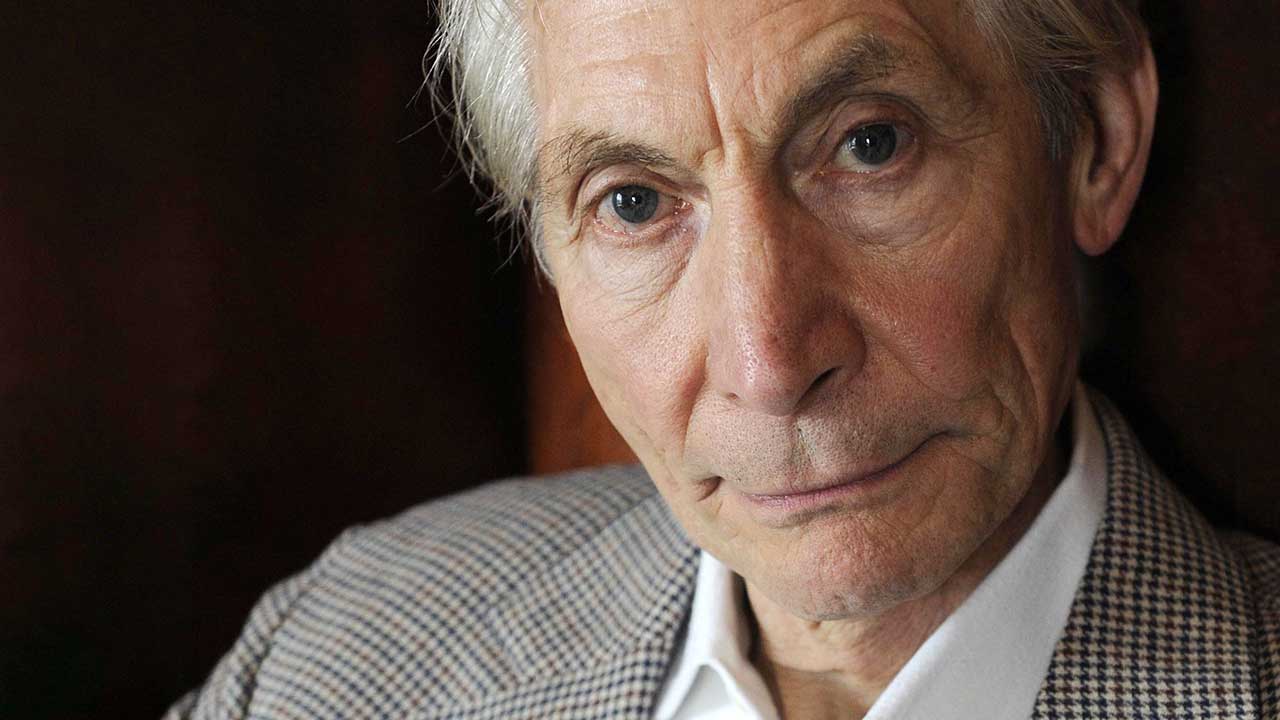

You’re in Vanity Fair’s Best Dressed Hall Of Fame, and you’re wearing a suit on a swelteringly hot day – matters sartorial are clearly very important to you. Do clothes maketh the man?

[His eyes immediately dart from the cricket. Now he’s fully engaged] No, they don’t, but they help make the man look great. Not everybody has it, not many people are interested, for a start, and the general public don’t care any more, so it’s all out the window, really.

I imagine a wardrobe of bespoke clobber is an excellent incentive to keep in trim.

Blimey, are you kidding? Not half. In the early to mid-80s I took drugs and that, and then by the mid-80s I stopped that but I drank rather heavily. I ballooned a bit and, God, I couldn’t get some of my trousers done up! That was it. I stopped everything. I lived on nuts, peanuts and sultanas. That’s all I ate for months.

That’s a marvellous incentive to clean up your act though.

Oh yeah, a well-made suit that you try to keep fitting you for 30 years is the incentive. I still wear clothes I bought 30 years ago. They cost so much money I refuse to let them go.

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #174, in August 2012.