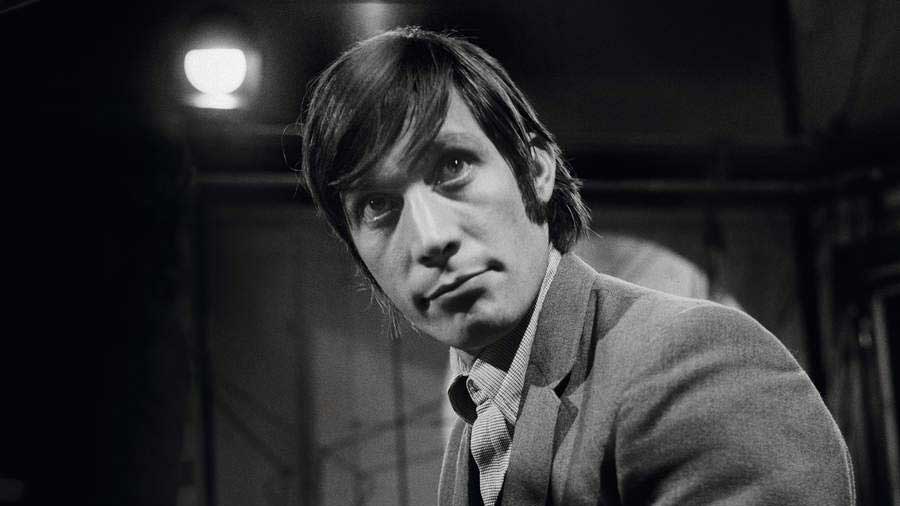

He was the most stylish man in rock’n’roll, with his easy, laconic, manner, bone-dry sense of humour, matchless wardrobe of bespoke Savile Row suits and deadpan, Buster Keaton stone face. He’d far rather talk about the cricket than about his illustrious 58-year career as the ever-reliable driving force behind the greatest rock’n’roll band in the world.

Charlie Watts was the Rolling Stone that even people who had no time for the Rolling Stones couldn’t help but like. There was never any old flannel with Charlie Watts. He spoke as he found. There was no diplomacy, no filter, no swagger and no pretensions to being in any way ‘cool’. And as a direct consequence Charlie Watts was invariably, and effortlessly, the coolest man in the room.

Even as the nascent Rolling Stones were being described as Neanderthals, Charlie stood apart. He didn’t say much. He didn’t have to. His aloof demeanour of wry detachment and dismayed indifference spoke volumes.

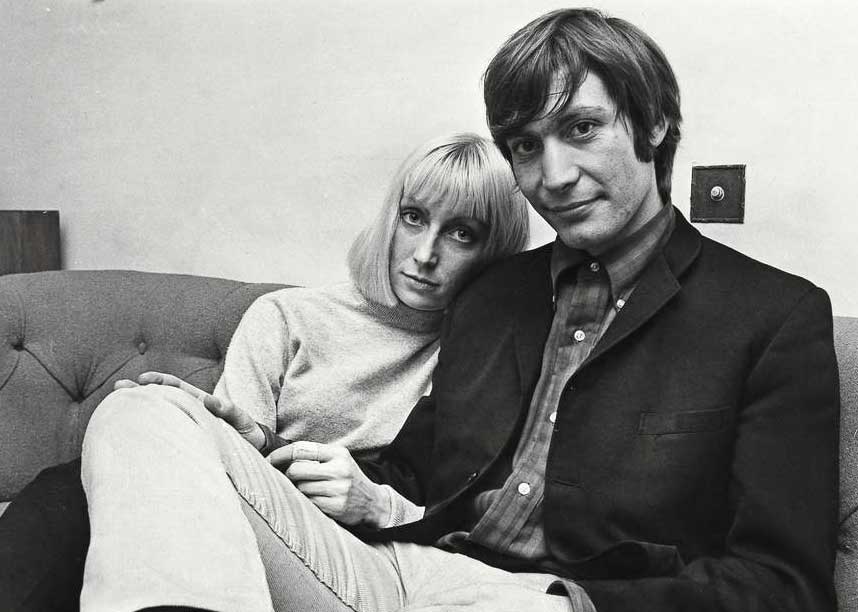

In October 1964, as hordes of nubile, compliant young women threw themselves screaming at the band’s feet, Charlie quietly slipped away to get married to his sculpture-student girlfriend, Shirley. And their marriage lasted the course. Rather than wile away on-road downtime with serial infidelity, the former graphic designer would assiduously sketch every hotel bed he ever slept in.

As his bandmates collected convictions and notoriety, Charlie collected American Civil War memorabilia, signed first editions and classic cars. Meticulously stylish to a fault, he’d have suits specifically tailored to complement each model (including his ultimate prize, a 1937 Lagonda Rapide - one of only 25 ever made). He’d dress, slip into the driver’s seat and contentedly relish its engine’s satisfying purr, but never disengage the handbrake, because Charlie Watts never learned to drive.

Devoted to jazz since boyhood, Charlie would far rather discuss Charlie Parker than the Rolling Stones; interviews would regularly disappear down unexpected worm holes, as any question regarding his central day job would veer off into sometimes surprising terrain: Arabian horse breeding, greyhound rescue, the world of difference between a Chicagoan drummer’s shuffle and that of a player weaned in New Orleans. And cricket. Always cricket.

Yet Charlie’s outwardly easy-going attitude concealed a steely core. He didn’t suffer fools gladly. Nor was he to be trifled with, as Mick Jagger found to his cost on the occasion that he famously opened a phone call to Watts’s hotel room with the incautious words: “Where’s my drummer?” Minutes later, Watts – freshly shaved, cologned and impeccably dressed – arrived to punch a startled Jagger full in the face, while delivering the immortal caution: ““Don’t ever call me your drummer again. You’re my fucking singer.”

Charles Robert Watts was born in University College Hospital, Bloomsbury on June 2, 1941. His father Charles Richard Watts had been in the Royal Air Force during the war, before becoming a lorry driver for the London, Midland & Scottish railway. The Watts family, completed by Charlie’s mother Lillian and younger sister Linda lived in a humble prefabricated house in Pilgrims Way, Wembley, North-West London.

Young Charlie soon became friends with opposite neighbour Dave Green, and the pair soon discovered a common passion for jazz. They’d convene in their bedrooms to study a shared stack of 78rpm 10-inch shellac records (Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Louis Armstrong), and forged a lifelong friendship that culminated in the pair working together from 2009 (Green on bass, Watts on drums) with pianists Ben Waters and Axel Zwingenberger in the ABC&D Of Boogie Woogie.

After the family moved to Kingsbury, Charlie attended Tylers Croft Secondary Modern School, where he exhibited a flair for art, music, cricket and football. At 13 (having been inspired by Gerry Mulligan’s drummer Chico Hamilton and clandestine visits to the Flamingo Club in London’s Soho), he bought a banjo, took its neck off and used its body as a snare drum. The following year his parents bought him a drum kit, which he learned to play by practising along with his ever-growing collection of jazz records.

After perfecting his chops with a succession of local bands in coffee shops and clubs while attending Harrow Art School, and working in his first job as a graphic designer with Charlie Daniels Studio advertising agency, 17-year-old Charlie joined the Jo Jones AllStars, a step that marked his transition from playing modern jazz to rhythm and blues.

Juggling a burgeoning design career with paying gigs that he’d pick up on Soho’s Archer Street alongside fellow drummer and lifelong friend Ginger Baker, Watts’s reputation brought him to the attention of ‘the founding father of British blues’, Alexis Korner, who invited him to join his Blues Incorporated.

Watts had already committed himself to a design job in Denmark, but on his return to England (in February 1962) he accepted Korner’s offer. Concurrent to the rigours of yet another straight job (this time with advertising agency Charles, Hobson and Grey), Watts joined Blues Incorporated for their regular Rhythm &Blues Nights at the Ealing Jazz Club. Which is where he entered the orbit of four likely lads of no fixed haircut who were in dire need of a drummer.

Brian ‘Elmo Lewis’ Jones, Ian ‘Stu’ Stewart, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, regular faces on the London R&B scene, were gradually coalescing into a band that they intended to call the Rolling Stones, but in order to evolve into a credible proposition they really needed to secure the services of a drummer as adept as Charlie Watts. But they couldn’t afford him.

So they set about using all of their available charm to persuade him. Which, needless to say, didn’t work. Eventually, when they appended their singular charm with the tantalising offer of five quid a week, he ultimately crumbled, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Watts played his first gig with the Rolling Stones at the Ealing Jazz Club on February 2, 1963.

Upon joining the band (a month after the arrival of bass player Bill Wyman) Watts briefly moved in to the Stones’ infamously squalid flat in Edith Grove, Chelsea. And while Mick Jagger attended the London School of Economics, the rest of the band made a study of Chicago blues.

“Brian and Keith taught me about Jimmy Reed.” Charlie told me in 2009. “We used to sit on this bloody great gramophone thing at Edith Grove. Mick would go off to college and the three of us would sit there, after waking up at about one in the afternoon, and Brian would play Bright Lights, Big City.”

Following an eight-month residency at the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond, the Rolling Stones were brought to the attention of management team Andrew Loog Oldham (who’d formerly worked as a publicist for both Bob Dylan and The Beatles) and Eric Easton, who secured them a record deal with Decca Records.

On June 7, 1963, the Rolling Stones (freshly trimmed to a quintet following Oldham’s ruthless demotion of Stewart from full band member to piano-playing road manager) released their first single, a perky cover of Chuck Berry’s Come On, and subsequently proved to be quite popular. In fact, just six years, eight No.1 singles and eight UK top-five albums later they were being customarily introduced to audiences on their 1969 US tour as ‘The Greatest Rock’N’Roll Band In The World’.

“I didn’t believe it, really,” an ever self-effacing Charlie confided to me as we discussed the Stones’ trademarked title back in 2012 while watching the Test match. “What about Little Richard? Then you have Dave Bartholomew and Fats Domino. Chuck Berry’s studio band – there isn’t a better rock’n’roll band. That’s where we got it from. Roll Over Beethoven by everybody else is a joke, really. We came close sometimes with Little Queenie or Around And Around.”

As drug busts, infamy and mayhem plagued the Stones’ 60s, culminating in the tragic death by drowning of Brian Jones in July ’69, and the brutal murder of African-American fan Meredith Hunter by Hells Angels at a free Stones show at Altamont in December that year, Charlie Watts kept a characteristically cool head. He wrote and illustrated Ode To A High Flying Bird, his personal tribute to jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker, further utilised his artistic training to design successive Stones album sleeves and, on March 18, ’68, celebrated the birth of a daughter, Seraphina.

During the 70s, as the Rolling Stones continued to bolster their status as the world’s biggest band (initially with Jones’s replacement guitarist Mick Taylor, and latterly, from ’75, Ronnie Wood) via a dazzling run of era-defining albums and singles (Sticky Fingers, Exile On Main St., Goats Head Soup, Some Girls; Brown Sugar, Tumbling Dice, It’s Only Rock ‘N’ Roll, Miss You), Charlie Watts compounded his reputation as an arbiter of style by increasingly suiting, booting and, in ’76, adopting an almost counter-revolutionary French crop haircut that served only to draw attention to his singular sartorial sharpness.

As the cricket action continued to unfold at Trent Bridge in 2012, I finally wrestled Charlie’s full attention away from the match by enquiring: “Do clothes maketh the man?”

“No, they don’t,” he replied, “but they help make the man look great. Not everybody has it. Not many people are interested, for a start, and the general public don’t care any more, so it’s all out the window, really.”

It’s a sweltering afternoon in late May, but Charlie is wearing a Prince of Wales check suit. Of course. “I should have turned up today in a pair of shorts and a T-shirt. The thought of that is horrendous.”

As the Rolling Stones’ stratospheric career continued to play out in its regular hurry-up-and-wait schedule of tour after album after tour, Charlie’s life ticked by comfortably. He would complain (famously observing in ’86 that his previous quarter-century with the band could most accurately be defined as “work five years, and twenty years hanging around”), but it was a routine that suited his style, that allowed him time out to indulge other musical passions: he’d record blues alongside Howlin’ Wolf in 1971; play R&B with Ian Stewart’s Rocket 88, and release jazz albums with his own Quartet, Tentet and, ultimately, realising boyhood big-band dreams, Orchestra.

But when the Rolling Stones juggernaut temporarily halted in the 80s, as a direct result of a prolonged feud between Jagger and Richards, which took the band off the road for an unprecedented seven years, Charlie’s life went into free-fall.

“Everyone I admired was either a junkie or an alcoholic. It’s not something to be proud of, but it’s true,” Charlie told me in 2009. “It was a world that was very glamorous to me, and one that I wanted to be in from the age of thirteen. I used to go to all-nighters down at the Flamingo. That’s where I first met Ginger Baker and Phil Seamen [arguably the greatest jazz drummer Europe ever produced, Baker’s mentor Seamen battled addiction and died in 1972 aged just 46]. I didn’t know it at the time, but half the people down there were junkies. It was the world I was in, so it wasn’t a shock to me when Keith took a liking to it.”

Having remained clean throughout the 60s and 70s (“Despite always being on the fringe of it, I was never really interested”), Charlie developed an unlikely mid-life addiction to heroin. With Jagger and Richards at loggerheads, and his daughter Seraphina expelled from school for smoking dope, Charlie’s intake of alcohol escalated dramatically.

It was at this point (’84) that the unfortunate “Where’s my drummer?” incident played out in Amsterdam. Eventually, boozing led to heroin, and by the end of ’86 “I hit an all-time low in my personal life and in my relationship with Mick. I was mad on drink and drugs. I became a completely different person. Not a nice one. I nearly lost my wife, family and everything.”

Eventually, a degree of good sense prevailed, with Watts weaning himself off heroin, by self-medicating even more alcohol, before the ever-dapper drummer finally elected to clean up completely for the most practical, and indeed stylish, of reasons.

“I stopped the drugs, but I drank rather heavily, and I ballooned a bit,” Charlie, a recent contender for The Daily Telegraph’s ‘World’s Best Dressed Man’ title and member of Vanity Fair’s ‘International Best Dressed List Hall Of Fame’, admitted as the wickets fell in 2012: “And god, I couldn’t get some of my trousers done up. That was it. I completely stopped everything. I lived on, as Keith always reminds me, nuts, peanuts and sultanas. That’s all I ate for months. I went from Dracula to a slightly bloated Dracula, to this emaciated, little thin thing.”

That’s a marvellous incentive to clean up your act though, isn’t it? “Oh yeah, a well-made suit you try to keep fitting you for thirty years is the incentive. I still wear clothes I bought thirty years ago. They cost so much money I refuse to let them go.”

With the Rolling Stones once more finding equilibrium and Watts reclaiming mastery of his waistline, the decades passed. Every few years he’d be persuaded back on the road, but in the intervening periods he’d return to Halsdon Arabians, the Arabian horse stud farm that he ran with his wife, Shirley, in Dolton, Devon.

In 2004 he faced a diagnosis of lung cancer, but following a course of radiotherapy, went into remission. As startlingly matter-of-fact as ever, when I asked him in 2012 if he’d read Keith Richards’ recently published autobiography, Life, he simply replied: “No, I don’t have to. I know him.”

Sadly, Charlie never felt the urge to write his own.

“I wouldn’t know what to say… As you’ve just found out. I’m naturally very private. And forgetful. I wouldn’t want to talk about half the things, and I forget a lot. And then you have to do all that bullshit: press and all that. It’s just too much. I’m not really that interested in talking about me… Me, and the Rolling Stones, actually.”

And that was Charlie Watts: an extraordinary talent; the ultimate rock’n’roll drummer; the quintessential English gentleman who provided the backbeat for all of our lives for the best part of six decades; but who never really understood what all the fuss was about.