It’s April 1994 and Magnum are having a night that is at once uproarious, surreal and melancholic. They’re in Guildford, in the middle of a UK tour. The venues they’re playing are smaller than they had been during the heady days of the late 80s, when their pomp rock had ascended to the nation’s arenas.

After a show at the local Civic Hall, Tony Clarkin, who has piloted the band for three decades, holds court in the bar of their nondescript hotel. A warm, engaging man, the guitarist is splendid company. Ploughing his way through enough brandy to fell an elephant, his soft Brummie accent becoming more resounding with each drink, he rattles off one war story after another – most libellous, all hilarious and each having a punchline founded on some disastrous decision or other that had thwarted his band.

During one particularly ribald account, the night manager of the hotel interrupts Clarkin. A nervous young lad, he gently informs him that the other occupants of the bar had complained about his language and asked if he wouldn’t mind toning it down.

“I’m so dreadfully sorry,” Clarkin replies in a fruity baritone, “but you’ve mistaken me for someone who gives a fuck.”

Booze-fuelled high jinks aside, just below the surface Clarkin seems weary at fighting Magnum’s long-running battle. He smiles when he recalls how they’d spent £500,000 on 1990’s Goodnight LA album in a bid to crack America and then failed to get it released there, but a trace of bitterness cuts through. He’s perhaps found himself helpless too many times at the vicissitudes of the music business.

All too clearly, he would be able to recall the saga that engulfed the making of Magnum’s landmark third album, Chase The Dragon. Had circumstances been different, Clarkin might now look back at it as his and Magnum’s grandest hour. His coming of age as a songwriter, on it he drove his band to new heights.

Yet Chase The Dragon was beset by ill luck and rather than elevating Magnum, it almost broke them and their leader. That night in Guildford, how little must have seemed changed. Within months, he had split Magnum.

It's late 2012. Clarkin, along with singer and faithful lieutenant Bob Catley, and Magnum’s other stalwart, keyboardist Mark Stanway, are sat sipping mugs of tea in their own Mad Hat Studios. Housed in an old red brick farmhouse, the studios are located down a muddy track in the countryside bordering Wolverhampton.

Still the engaging raconteur, Clarkin does much of the talking. By contrast, Catley – short and round of face, the latter of which crumples into a concertina of lines when he smiles – is a man of few quotable words, preferring for the guitarist to do the talking, interjecting only if it is to agree with whatever is being said. While this may make prospect of a night in the pub with him seem one of long and uncomfortable silences, it suggests he’s been the ideal blank canvas for Clarkin to project his songs on to all these years.

The likeable Stanway was memorably informed by a fan at that gig in Guildford that he reminded her of “David Coverdale after a thousand breakfasts”. He cuts a slightly less well-fed figure these days.

The three of them re-assembled as Magnum in 2002, since when they have put out a string of solid albums. The latest, 2013’s On The Thirteenth Day, is a timely echo of Chase The Dragon. Both have sleeves designed by fantasy artist Rodney Matthews, both are unapologetically grandiose. On each the standout track is an epic attaching mystical significance to the act of being on stage (All The Dreamers on the latest album; Sacred Hour on the elder). That Chase The Dragon’s influence remains so prevalent is perhaps no surprise. In many ways it is Magnum’s most significant and undervalued album.

Clarkin and Catley formed Magnum in their native Birmingham in 1972. Both had been fixtures on the local club scene. Clarkin, who had trained as a ladies’ hairdresser, was a Beatles fanatic and aspirant songwriter. Catley had styled himself on Mick Jagger. They first met at a gig at a West Midlands technical college neither recalls the name of.

“He was prancing about, slinging this long scarf around his neck,” says Clarkin of Catley. “I thought he was a bit of a pillock actually.”

The nascent Magnum cut their teeth as the house band at Birmingham club the Rum Runner, later the scene of Duran Duran’s first shows. It was a shortlived tenure – they were sacked for sneaking Clarkin’s songs into their covers-only sets. To earn a crust, they took to being a band-for-hire for touring American stars such as Del Shannon, of Runaway fame, and soul singer Eddie Holman.

When another local musician, Jake Commander – guitarist in one of Jeff Lynne’s pre-ELO bands, The Andicaps – set about building his own studio, Clarkin saw a chance to record his own songs. He offered to help with the construction, deferring wages in lieu of free studio time for the band. Magnum taped their first demos at the completed Nest Studios in February 1974. The following September, via a one-off deal with Columbia Records, they released their first single, a cover of The Searchers’ Merseybeat staple Sweets For My Sweet. It didn’t trouble the charts.

“Like every band did, we went to London and tried to get a record deal,” Clarkin recalls. “We’d sit in these offices playing our songs to guys who smoked cigars and told us we were crap.”

In 1975, Magnum finally signed to Jet Records. This brought them into the orbit of Don Arden, the notorious impresario who’d founded Jet. Christened the ‘Al Capone of pop’, Arden had handled the careers the Small Faces and the Nashville Teens, developing a reputation as both a fearsome negotiator and financial shark. Once finding himself being questioned about missing monies by John Hawken of the Nashville Teens, Arden hauled his interrogator to the second floor window of his Carnaby Street office and threatened to throw him out of it.

By the time Magnum signed to Jet, Arden was managing Black Sabbath and ELO, the latter also being his label’s prized cash cow. It was Arden who determined his new band’s image.

“At the time I had these big sideburns and always wore a hat,” says Clarkin. “Don walked up to me at the bar after a gig we’d done and said, [affects Arden’s growling tones] ‘That’s the look for this band – Charles Dickens!’ Other than that, we didn’t have that much to do with him – it was his son David that had signed us. Don took us out to meals, but we never, ever got a statement out of him showing what we were earning.”

“He fancied my mom something rotten though,” adds Catley drolly.

Magnum’s first records for Jet, 1978’s proggy Kingdom Of Madness and the following year’s imaginatively titled Magnum II, barely made a ripple. While they’d built a small but loyal following through constant gigging in the UK, at Jet they were dwarfed by ELO and nudged further still down the pecking order by the label’s newest signing, Ozzy Osbourne. Recently sacked by Black Sabbath, Osbourne’s solo career was being guided by Don Arden’s daughter, Sharon.

Such was the situation when Clarkin began writing Chase The Dragon. He nonetheless recalls the period as being an optimistic one. Jet had stumped up for a state-of-the-art studio, Richard Branson’s Townhouse complex in West London, and hired crack US producer Jeff Glixman. Glixman had made his name recording US soft rockers Kansas, then one of Clarkin’s favourite bands. The guitarist’s new songs were also a step up from anything he’d done before.

“It felt like a new beginning for us,” he reflects. “Jeff was an uplifting guy to be around, full of great ideas. The whole feeling around us at the time was very up.”

Before recording began, the band had to find a new keyboard player after the previous incumbent, the excellently named Granville Harding, had departed at the end of a tour with Def Leppard. Promoter Maurice Jones introduced them to Stanway, a regular face on the Birmingham music scene. Clarkin recalls the hapless Stanway’s audition being a chaotic affair.

“We asked him to come to this community hall in the middle of nowhere,” he says. “To be honest, we were all very drunk and not the least interested in hearing his keyboards. So we stuck him in a room and told him to learn [Kingdom Of Madness track] Invasion, while we went out and made a bomb out of all the flash powder left over from the tour. While he was in the back playing, we were letting off this horrendous thing.”

Unbowed by this initiation, Stanway has fond memories of making Chase The Dragon. Recording its signature song, Sacred Hour, he played the sweeping instrumental intro on the Steinway Baby Grand piano Mike Oldfield had used for Tubular Bells.

“The song itself was already written,” he says, “but I just happened to have this piece of music, something I’d nicked off my wife. I put it into the right key and it worked perfectly. That was a lovely sounding instrument,” he concludes wistfully.

At Townhouse, Magnum and Glixman worked fast. Chase The Dragon was recorded in just 13 days. Aside from Glixman being rushed to hospital one night with suspected food poisoning having eaten an especially virulent curry, the sessions passed without incident. Lovely or not, Oldfield’s piano was subjected to fearsome treatment during the recording of opening track Soldier Of The Line.

“To get the crashing effect at the start of it,” notes Stanway, “I had to slam the piano lid on the floor more than 50 times – showing a total lack of respect. It actually sounded fine the first time, but this lot took the piss and made me do it over and over again.”

Laying down another of the album’s most enduring songs, The Spirit, Clarkin wanted a harpsichord for the bridge and chorus.

“This was in the days before you could approximate the sound of one on a synthesiser,” says Stanway, “so we hired an original 18th century instrument. There was no tomorrow with budgets back then – no one got paid anyway. It was a priceless instrument. Two minders came with it and had to keep it in sight the whole time. I remember them putting on white gloves and very, very carefully taking it out of its case and setting it up. Then the look of absolute horror on their faces when I sat down at it and started playing boogie-woogie.”

There was, says Clarkin, a tangible sense of excitement when the band gathered to hear a playback of the finished album. “Ozzy and Randy Rhoads were there too,” he says. “They’d been staying in one of the Townhouse suites. We were playing The Spirit back through these whacking great speakers and when it got to the chorus Ozzy was like, [reels back] ‘My God, man!’ We’d never heard anything that sounded so big.”

All that appeared left to do was decide upon a title. Having earmarked The Spirit for it, Clarkin had a late and unlikely bout of inspiration.

“One of the roadies pulled me to one side and asked me if I wanted to chase the dragon,” he recounts. “I had no idea what he was talking about. But he got out some silver paper, a lighter and went through this whole ritual. I had a smoke and instantly it was like, ‘Woooah!’ I was totally out of my mind. I hadn’t a clue what chasing the dragon meant and I didn’t think anyone else would either, but it seemed a great title for an album.”

Flushed with the knowledge he’d made a fine record, Clarkin sat back and waited for Jet to release it. And waited. In the end, two years would pass before Chase The Dragon saw the light of day. The problem was that Jet were struck down by financial problems. Having released such blockbuster albums as A New World Record and Out Of The Blue in the 70s, ELO’s commercial star had begun to fade in the new decade.

As Magnum completed Chase The Dragon, Jeff Lynne was pouring his efforts into the soundtrack to the ill-fated movie musical Xanadu. At the same time, he’d begun asking Arden difficult questions about how much he was worth.

“The answer was not as much as he’d thought,” says Clarkin. “As a result, all of Jet’s money became tied up – or so we later heard. It was a horrible period for us. Jet hadn’t paid for the record so the Townhouse refused to release the tapes to them. Things got very depressing. These great spans of time would go by and we weren’t able to do anything.”

Magnum survived on nothing but the £50 a week wage Jet paid each of them. Even then, Clarkin often had to badger the label for money.

“It had originally been £30,” he adds, “but I had to go in and tell them that we couldn’t live on that amount. In a way, the wage was a good thing. We were tearing our hair out, but at least we were still getting something. In those days we didn’t care about money, we just wanted to have a record out. I’ve absolutely no idea how many albums we sold through the whole Jet era. Never knew, couldn’t be bothered to ask. We were idiots, simple as that.”

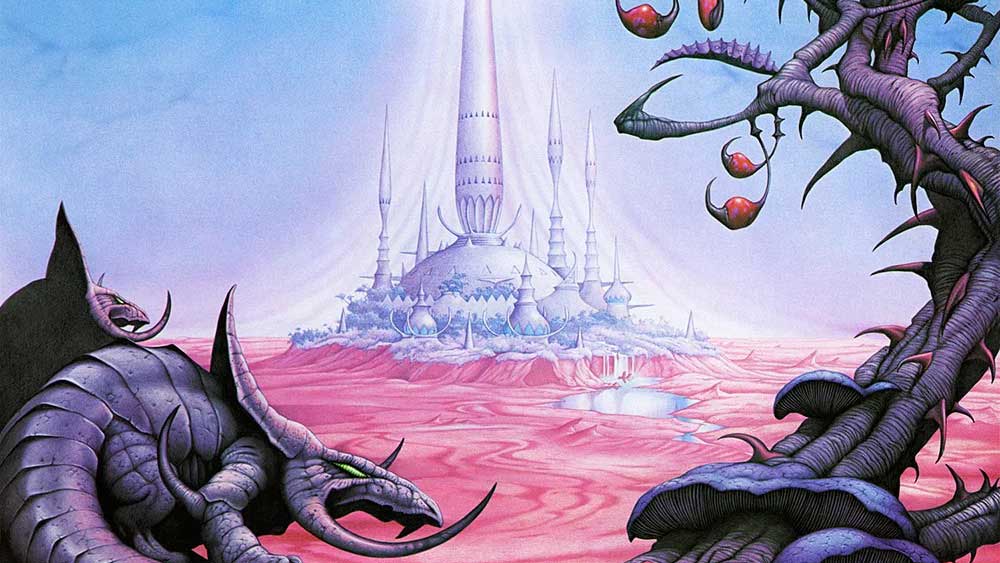

Chase The Dragon finally emerged on February 24, 1982 – the same week as Jimmy Page’s Death Wish II soundtrack and country crooner John Denver’s Seasons Of The Heart. Rodney Matthews’ cover art was lavish, depicting a pair of mystical dragons prowling a desert, a futuristic city looming on the horizon. Its precise meaning may not have been apparent, but in its original vinyl format it was gloriously extravagant. It would have been more opulent still had not Jet reneged on a promise to make it a gatefold sleeve.

At the time it came out, the NWOBHM was at its peak in the UK – Iron Maiden would soon top the charts with Number Of The Beast, their fellow prime movers Saxon and Def Leppard had released Denim And Leather and High ’N’ Dry respectively. That year would also herald acclaimed records from Judas Priest (Screaming For Vengeance) and Scorpions (Blackout), while Ozzy Osbourne’s Diary Of A Madman established him as a superstar in the US.

Next to these, Magnum’s more seasoned melodic rock seemed quaintly old fashioned, but there was a feeling too of timelessness to Clarkin’s work. For all the tribulations, Chase The Dragon was a triumph. Clarkin’s songs ran a gamut from punchy rockers like Walking The Straight Line to the magisterial closing ballad The Lights Burned Out. Soldier Of The Line, The Spirit and Sacred Hour, the latter perhaps Clarkin’s own finest hour, have lost none of their lustre.

The album charted at No.17, a commercial high for the band. Having sent them a congratulatory telegram, Jet financed their first – and only – US tour, a month-long engagement supporting Ozzy Osbourne in 20,000-seat arenas.

In March 1982, as Magnum prepared to fly out, Osbourne’s guitarist Randy Rhoads was killed in a plane crash and the tour ground to a halt. When it did resume, the band met with receptive audiences on America’s East Coast and through its southern states.

“It was a great experience,” says Clarkin. “We didn’t socialise with Ozzy much because Sharon was keeping a close eye on him. His band weren’t allowed to drink around him either, so they’d sneak into our dressing room every night for a beer. We had a bit of a sniff at America then – I think we even sold a few records. But of course, we never got to go back."

Keen to capitalise on Chase The Dragon’s momentum, and with a stockpile of material, Magnum released their next album within a year. But their intention to work with Jeff Glixman again came to nothing as the increasingly cash-strapped Jet insisted Clarkin produce the record himself.

“We ended up in a studio that was 40 years out of date,” he says with a wry smile. “I was in there at 3am one morning doing a very loud guitar solo when a whole wall suddenly opened out. An old woman walked through it going, ‘Will you shut that bloody racket up!’ Turned out she lived in a flat next door.”

The Eleventh Hour, its title a nod to common practice at Jet, had its share of excellent Clarkin songs. Yet he was no producer, and its muddy sound and a lack of promotion meant it failed to repeat its predecessor’s success. It would be a further two difficult years before the self-financed On A Storyteller’s Night went some way to restoring Magnum’s fortunes.

There would be no such revival in Jet’s fortunes. In quick succession, ELO and Ozzy Osbourne left the label and it sunk into a painfully protracted decline. In 1991 Jet released its final record, erstwhile Eurovision Song Contest winner’s Bucks Fizz’s Live At The Fairfield Hall, Croydon. Don Arden, once so flush with ELO’s riches that he bought Howard Hughes’ old house in Beverley Hills, died of Alzheimer’s in 2007.

Of the Magnum line-up that recorded Chase The Dragon, drummer Kex Gorin lost a long battle with cancer in December 2007, bassist Colin ‘Wally’ Lowe was last spotted running a B&B in Spain, and Stanway left the band in 2016. Clarkin and Catley soldier on. They are, the guitarist readily acknowledges, still indebted to Chase The Dragon.

“Definitely. Later on, I got browbeaten into the fact we had to have hits and lost the plot of what Magnum was about. I hated that time, couldn’t stand arenas – it all sounded crap to me.”

And when he listens to Chase The Dragon now, what does he think? The response is typical Tony Clarkin.

“Couldn’t tell you, mate,” he says, brow furrowing. “I haven’t played it for years.”

The original version of this feature was published in Classic Rock 181, in March 2013.