In the aftermath of Chick Corea’s untimely death – he died of what was officially described as a rare form of cancer on February 9 – many fans struggled to process the loss. One reason for this was that Corea had continued to be vital and active right up until the end. Some artists slow down, kick back, retreat from public performance. Not Corea. A creative dynamo with a prodigious output that runs into hundreds of releases, Corea didn’t seem to get the memo that players on the cusp of being an octogenarian should be taking things easy. Corea was genuinely inquisitive and had an interest in music that took him far beyond the boundaries of his chosen field. That was why listeners never quite knew what to expect with him.

Already a rising star and composer of note, he joined Miles Davis’ band in the late-60s. He first appeared in the post-bop Filles De Kilimanjaro line-up in 1968 where he added his pungent electric piano as the Davis ensemble underwent a chrysalis-like development. Corea stayed to contribute extra colour to 1969’s classic In A Silent Way and the ground-shaking Bitches Brew. That electric-era Miles threw the switch on a plethora of players that would shape the world of fusion, including Corea. Record companies were eager to back the next big thing and musicians blessed with remarkable instrumental skills were also keen to play to the ever-expanding youth rock audience. Early adopters of the jazz-rock direction included Joe Zawinul and Wayne Shorter who launched Weather Report in 1970, Herbie Hancock and his Afro-space fusion release Mwandishi and the funk-orientated Headhunters in 1971 and 1973 respectively, and, somewhat overshadowing them all, John McLaughlin going full supernova with Mahavishnu Orchestra in 1971.

Corea, by comparison, was late to the plugged-in party, having spent part of that period with an acoustic Return To Forever, who released two Latin-infused albums that included sax player Joe Farrell and vocalist Flora Purim. Admirers at their 1972 Carnegie Hall shows reportedly comprised legendary bassist and bandleader Charles Mingus at one end of the spectrum and Mick Jagger at the other.

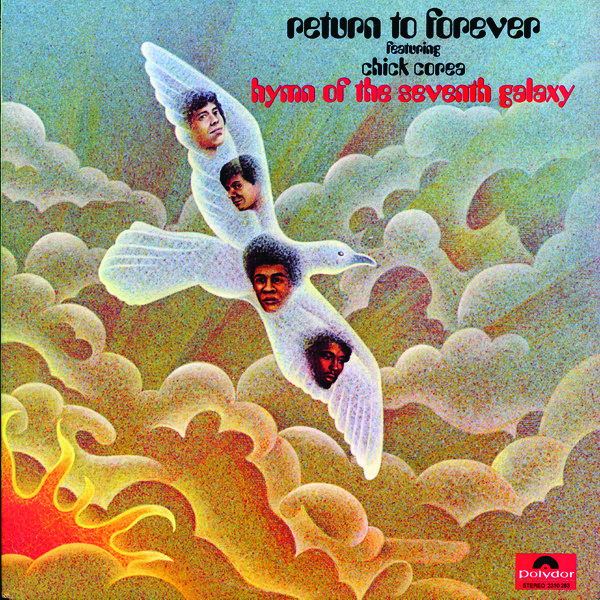

Having seen the huge audiences that were flocking to Mahavishnu shows, Corea was inspired by what McLaughlin was doing. Speaking to DownBeat magazine in 1988, Chick explained his change in direction. “John’s band, more than my experience with Miles, led me to want to turn the volume up and write music that was more dramatic and made your hair move.” With Return To Forever’s 1973 album, Hymn Of The Seventh Galaxy, he more than achieved that goal. Stanley Clarke, who had been on the previous two records, added an electric bass that drilled deep into the pianist’s quicksilver compositions. Beautifully underpinned by the incoming Lenny White, whose drumming had also been part of Miles’ electric entourage, the album’s real secret weapon was guitarist Bill Connors. His muscular style and melodic phrasing meshed with Corea’s ornate and sometimes circuitous compositions gave RTF both body and a distinctive edge.

Connors bailed after that album but Corea found an able replacement in the then-19-year-old Al Di Meola. Corea wasn’t interested in RTF as a vehicle for jamming, but rather a place to extend instrumental ambition and expand the scale of his writing. Across the albums Where Have I Known You Before (1974), No Mystery (1975) and arguably the artistic height of the period, 1976’s Romantic Warrior, they raced over jazz, rock and classical forms with the skill of a surgeon and the speed of a jet fighter. That combination of adrenalised velocity could sometimes be overpowering and the band drew some criticism for the elevation of technique above substance. Not that the public seemed bothered. Corea, as with one or two of his fellow brothers and travellers in the electric diaspora, became that rare thing: a jazz player with a certified Gold disc under his arm.

At the height of their powers, Return To Forever’s hectic musical direction probably had more in common with some of progressive rock’s headliners, such as ELP and Yes, than their jazz-rock brethren, often maintaining only a slender tether to their jazz origins as they throttled up in search of escape velocity. By 1977’s Musicmagic, although the core quartet had burned out, Stanley Clarke was still onboard for a group augmented by horns and Corea’s wife, Gayle Moran, a noted keyboardist and one-time member of the late-period Mahavishnu Orchestra.

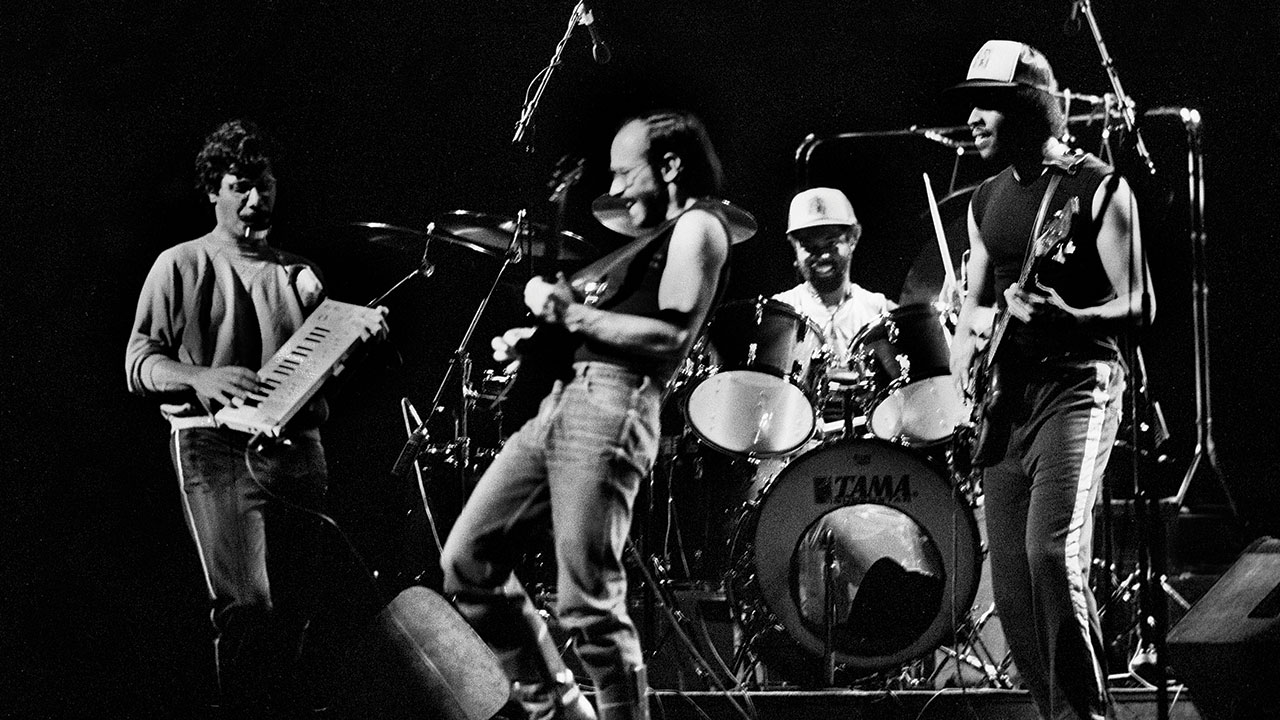

From 1982, RTF became an occasional vehicle, although the results of their reunions sometimes lacked the burn and drive of the past. Their 2008 ill-tempered reprise saw them part company with Di Meola and was thankfully eclipsed by a spectacular tour in 2011 with guitarist Frank Gambale and violinist Jean-Luc Ponty joining forces with Corea, Clarke and Lenny White. Although now in their 50s and 60s, their playing was up to the demands of the repertoire, albeit at a slightly slower, and more enjoyable tempo. Highlights were captured on 2012’s live set The Mothership Returns; a bravura performance, filled with a freewheeling expressiveness and a surprisingly nimble reinvention of the RTF brand.

Regardless of whether he was working in rock or more conventional pianistic settings as a composer, Corea never stopped pushing and stretching his writing. Both 1983’s Lyric Suite For Sextet and 1985’s Septet contain his urgent, propulsive melodies set into motion by a string quartet, the former augmented by Gary Burton’s vibraphone and the latter by flute and French horn string players. These pieces are especially convincing as classical music in their own right.

What Chick Corea had in abundance was energy and range. He’d investigate a different take on fusion with The Elektric Band in the 90s and straddle straight ahead jazz and rockish audacity with the Five Peace Band in the 2000s, tag-teaming with John McLaughlin once again. In the 2010s, he revisited the piano trio format with Trilogy featuring bassist Christian McBride and drummer Brian Blade. Skipping between joyous improvisation and tight melodic and structural control, the results are especially lucid.

There’s simply not enough space here to list the diversity of styles that Corea embraced, explored, and made his own across more than six decades as a pioneering musician. If all you know of Chick Corea is his work with Return To Forever, you’re missing out on a remarkably rich and deeply fulfilling back catalogue.

Highlights from a storied career that should not be overlooked or underestimated include 1968’s Now He Sings, Now He Sobs, an astonishing trio with future Weather Report bassist Miroslav Vitouš and Roy Haynes’ intricate drumming. The works of Circle for the Blue Note label and 1971’s Paris Concert with Anthony Braxton go deep into experimental playing where listening is as vital as any notes that might be played. About as far removed from jazz-rock, they nevertheless burn with a truly fierce originality that shows another facet of Chick Corea’s artistic restlessness, creativity and expressive depth.

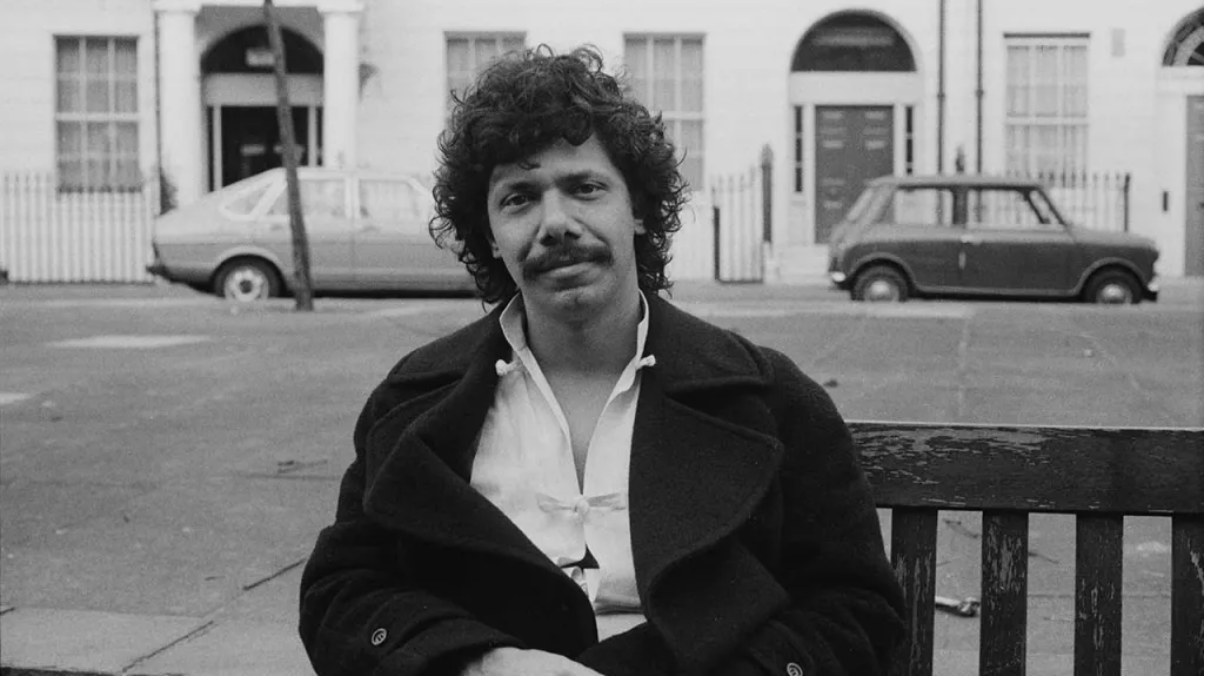

Although the man himself may be gone, Corea leaves behind an impressive body of work. Quick to smile and blessed with an inquisitiveness that never seemed to dim or give way to cynicism, his portrait would often grace an album sleeve. Oddly enough, when this writer thinks of Chick Corea it’s the cover of Return To Forever's self-titled debut on ECM in 1972 that almost immediately comes to mind. Instead of a photo of the pianist, it’s a portrait of a sea bird, wings spread wide, cutting through the air, blurred in flight above a surging, blue ocean and a sliver of land receding to the vanishing point. It seems emblematic of Corea, a spirit in flight, searching for a new horizon.