According to Fish, Marillion owe it all to Terry Wogan. On May 20, 1985, the band made their one and only appearance on the Irishman’s BBC chat show. Back then, Wogan was prime-time TV, and the perfect shop window for any group with a single to promote.

At the BBC Television Theatre in Shepherd’s Bush, Marillion performed what the show’s host called their “current smasheroonie”, Kayleigh. At the end, lead singer Fish gave a shy smile to the camera. And after that, he says, everything changed.

The man born Derek Dick is remembering Marillion’s Wogan performance almost 30 years later. After the show, EMI’s Head Of Promotions, Malcolm Hill, took him aside. “And he said to me, ‘That little smile you did at the end broke every mother’s heart in Great Britain.’”

Soon after, Kayleigh was at No.2 in the charts, giving Marillion the biggest hit of their career. “The Wogan show was what did it,” says Fish. “That lit the touchpaper on the whole thing.”

In June, Marillion’s third album, Misplaced Childhood, toppled Bryan Ferry’s Boys And Girls from the top of the chart. Against all expectations, Marillion had become one of the biggest bands in Britain. “Suddenly we went from being this relatively unknown progressive rock group to a band with a big hit single and album,” Fish marvels. “Misplaced Childhood was us sticking one finger up at the business and saying, ‘Fuck you! This is a real band.’”

Misplaced Childhood turns 30 this year, and remains the biggest-selling album of both Marillion’s and Fish’s careers. The singer, who’s now planning to retire from touring, will celebrate its birthday by performing the album in full later this year.

Marillion, meanwhile, are busy writing a new album. You sense that the past – especially their past with Fish – sometimes seems like a foreign country. But Misplaced Childhood is an album they remember fondly. As keyboard player Mark Kelly admits:

“It was the album that saved us.”

To their dedicated and growing fanbase in 1984, it might have seemed as if Marillion could do no wrong. They’d had five Top 40 singles and two Top 20 albums with 1983’s Script For A Jester’s Tear and ’84’s Fugazi. But, in fact, they were actually in danger of being dropped by their record company.

“We’d got ourselves into a bit of a hole with EMI,” explains guitarist Steve Rothery now. The hole had grown bigger after Marillion spent almost as much money on the video

for their last single, Assassing, as they’d done on the whole of Fugazi: “And we were liable for 50 per cent of the costs.”

“Looking back, we were on a bit of a knife edge,” adds Kelly. “Script For A Jester’s Tear had sold about 120,000. Fugazi cost twice as much but sold a bit less. If we carried on the way we were going, we weren’t going to be financially viable.”

It was a precursor of the situation Marillion found themselves in at the end of the 90s, and which they resolved with 2001’s crowd-funded Anoraknophobia. In 1984, though, they did what any struggling rock band would do: they put out a live album.

Real To Reel, released in November, was recorded at dates in Montreal and, less exotically, Leicester. It cracked the Top 10 and sold well in Europe: “Which gave the label an inkling that it might be worth sticking with us for one more album,” Kelly says.

However, Marillion were in no hurry to tell EMI that their next studio release was a concept album. “That,” admits Rothery, “might have been the kiss of death.”

The concept for Misplaced Childhood came to Fish during an LSD trip. The singer had returned to his house in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, at the end of the Fugazi tour, feeling burnt out, but “knowing we had a difficult third album to write”.

Soon after, an envelope arrived in the post with a note from an old girlfriend – “It read: ‘I think you might like this’” – and a tab of ‘white lightning’ acid. “I was bored, sitting on my own one night, so I took half of it,” Fish recalls. “Then I thought, ‘Oh, this is rubbish, it’s not working,’ and I took the other half…” He pauses, then lets out a throaty laugh. “Aye, that old mistake.”

It was seven o’clock on a warm summer’s evening. With the world around him growing increasingly fuzzy, Fish jumped on his bicycle and rode to Steve Rothery’s cottage nearby.

“In those days, Fish and I were on very good terms,” says the guitarist. “We were the two bachelors in the band. We socialised together a lot.” Does he recall Fish being under the influence? Rothery laughs: “Yes, he probably was.”

Fish remembers the pair of them watching the recent film adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s novel, Tess Of The D’Urbervilles, starring the beautiful German actor Nastassja Kinski. “Steve had a particular thing about her,” laughs Fish.

But when the drug’s effects became too much for Fish, he asked Rothery to drive him home. “When I got back to my house, I thought, ‘OK, let’s use this.’”

Fish put on a record, crouched on the floor, grabbed a notepad and began what he calls “stream-of-consciousness writing”. At the time he had a print of the American artist Jerry Schurr’s painting Padres Bay on the wall of the house (“I still have it. It’s hanging in my bedroom.”). Schurr’s image of the sea and mountains was so hypnotic, Fish felt that he was actually inside the picture. The hallucinogenic experience paid off.

“That night I got the whole basis for what became side one of the album,” Fish says. “Entire phrases and lyrics from that notebook ended up on the finished record.” One of which, Pseudo Silk Kimono, became Misplaced Childhood’s opening track. As the LSD wore off, and he drifted back to normality, Fish knew he had to tell someone: “I phoned up Steve and said, ‘I got it. I’ve nailed it.’”

Ultimately, the theme running through Misplaced Childhood was inspired by the 27-year-old Fish’s life so far: watching childhood fade with each passing year; the thrill and attendant pressure of being in a rock band; and, crucially, the recent demise of his relationship with girlfriend Kay. It was a concept album, yes, but one very much grounded in reality.

Writing sessions for Misplaced Childhood began in autumn 1984 at Barwell Court, a freezing cold Victorian pile located in Chessington, Surrey. “I’d sit in the TV room with the fire on, writing lyrics,” remembers Fish, “and hear the others in the next room coming up with the music.”

“My memory is that it all came together very quickly,” says Kelly. “We’re in the process of writing an album now and we were marvelling at how we managed to write most of side one of Misplaced Childhood in a week.” That’s Pseudo Silk Kimono, Kayleigh, Lavender, the multi-part Bitter Suite and Heart Of Lothian. “If only all albums were that easy,” he sighs.

At Barwell Court, the band were also introduced to their new producer, Chris Kimsey. “I wasn’t familiar with Marillion at all,” says Kimsey now. “But their A&R man, David Munns, was a good friend of mine and told me to check them out. I went to the writing sessions at Barwell Court and immediately fell in love with them.”

Kimsey’s CV included engineer credits for Peter Frampton’s Frampton Comes Alive! and the Rolling Stones’ Some Girls. “We were a bit intimidated by Chris at first,” admits Fish. “But he turned out to be such an easy-going guy… and he’d done [ELP’s] Brain Salad Surgery.”

Better still, Kimsey didn’t need to be sold on the idea of a concept album. “I was totally into that,” he says. “Did EMI want a concept album? I don’t think EMI knew what they wanted. They just wanted a hit.”

It was at Barwell Court that Marillion would compose that first hit. Fish remembers being in the TV room when he heard Rothery messing around with the riff that eventually became Kayleigh. “That riff originally came from me demonstrating to the woman that is now my wife how I wrote songs,” says Rothery. “I filed it away, and from such a little thing, our mortgage is now paid.”

Initially, Kayleigh was regarded as just another chapter in the Misplaced Childhood story. Nobody thought of it as a potential single. Fish’s bandmates also had reservations about the title and lyrics. The problem was that his recently ex-girlfriend Kay’s middle name was Lee, and her father’s pet name for her was ‘Kay-Lee’. There was no ambiguity about it.

“The band said [adopts blokey English accent], ‘Er, that’s about Kay. You can’t sing that,’” says Fish. “I said, ‘Why?’ They said ‘’Cos it’s too personal.’”

“I was the main one that objected,” recalls Kelly. “Kay had been Fish’s girlfriend ever since I joined the band. But they’d split up now, and I said, ‘No, we shouldn’t call it Kayleigh.’ And Fish said [adopts gruff Scottish accent]: ‘What do you want me to call it? May-be?’”

“I was a little bit uneasy about it,” adds Steve Rothery. “I knew Kay well and she was a lovely person. But I saw the song as Fish’s tribute to Kay… and how he threw away what they had.”

Either way, Fish refused to change the lyrics, which he has since claimed are about more than one of his ex-girlfriends. Kayleigh was staying put.

In the meantime, Marillion went back on the road for a pre-Christmas tour in November 1984. Their setlist now included most of the first side of Misplaced Childhood. “Kayleigh wasn’t completely finished yet, though,” says Fish, “and if you listen to bootlegs from that tour, you can hear me ad-libbing.”

Marillion demoed their new material at Bray film studios in Berkshire before heading to Berlin’s Hansa Ton Studio in March ’85. Chris Kimsey had just produced Killing Joke’s Night Time album and its hit single Love Like Blood at Hansa. “It was also cheap,” says Mark Kelly, “which made sense if the record company were thinking about dropping us.”

Nevertheless, there were worst places to make an album than Berlin. It was, says the keyboard player, “like the Wild West”. Or, as Fish puts it, “a playground for adults”.

Before reunification in 1990, West Berlin didn’t officially belong to the Federal Republic Of Germany. This meant its young male residents didn’t have to do national service as they would elsewhere in the country. Rothery says: “So it was full of young people, musicians and artists. There was a unique feeling about the place.”

Hansa Studios was in a converted town hall, and was steeped in history. The main ballroom, Der Meistersaal, had been used by the Nazis to hold propaganda concerts during World War II. It was at Hansa that Bowie had recorded his ‘Berlin trilogy’ of albums, Low, “Heroes” and Lodger, in the 70s.

Kimsey moved into a rented apartment in the suburbs. The band (Fish, Kelly, Rothery, bassist Pete Trewavas and drummer Ian Mosley) moved into the Hervis Hotel, which overlooked the Berlin Wall. Each morning the band were greeted by the sight of barbed wire, graffiti and sentry towers.

Initially, there were teething problems in the studio. The Neve mixing desk on which Kimsey was working had been damaged when Killing Joke set off a dry powder fire extinguisher over it a few months earlier. “It was noisy and knackered,” recalls Rothery. “In the first few weeks, everything we heard at the playbacks sounded very ordinary.”

Kimsey recalls Ian Mosley protesting that his drums “didn’t sound expensive enough”. Rothery says: “Once Chris EQ’d [equalised] everything, we were fine. But we had a real crisis of confidence to start with.”

That said, Kimsey’s assistant, engineer Thomas Steimler, soon had the band on side after demonstrating his great hustling skills. “Thomas phoned up [Austrian piano maker] Bösendorfer and told them there was a very famous English rock band in the studio and could they please send us a piano,” recalls Kelly. Soon after, a Bösendorfer Concert Grand arrived at Hansa and was carried up a flight of stairs to be delivered to the not-that-famous English rock band.

With their sound problems resolved and a new piano to play with, the band and their producer fell into a comfortable working pattern. “Start late afternoon,” says Steve Rothery. “Work till the evening, dinner, go out with Kimsey, drink a lot, come back to the studio and try and do some more work.”

‘Try’ being the optimum word. To achieve the exact sound he wanted, Kimsey recorded one vocal after persuading Fish to stick his head inside the “plastic igloo” surrounding the studio payphone. Fish, meanwhile, now mutters darkly about an “unidentified presence” in the studio while the band were playing the Perimeter Walk section of Blind Curve late one night. “The room where we were had once been an SS officer’s club,” he says. “I am convinced something else was there besides us. I sensed another presence.”

Then again, Berlin offered so many distractions, it wasn’t unusual for some band members to find themselves working while in a heightened state. “The city didn’t wake up until midnight,” says Kimsey. “If we had a day off, we’d go clubbing and all arrange to meet at the Cri Du Chat, a club that only opened at six in the morning.”

Tequila became the tipple of choice, consumed in such quantities that Rothery recalls some of the band and their entourage passing out during a late-night screening of Fritz Lang’s silent movie classic Metropolis: “It didn’t help that the subtitles, naturally, were in German.”

Chris Kimsey also became a victim of a boozy prank. While driving through Berlin, Marillion persuaded Thomas Steimler to crash his Volvo into Kimsey’s rental car, just for the hell of it. “Chris was in this Honda Jazz,” divulges Kelly, “and Thomas rammed straight into him at a set of traffic lights. And then we spent the next 20 minutes ramming into him, until the car was making the most awful noise and we had to ditch it… isn’t it strange how when you’re 22, 23 years old, you think you’ll never end up getting into trouble – and somehow we didn’t.”

“Oh, I could fill a book with stories about Berlin,” says Fish. “But you’ll have to wait for the book.”

Key moments include the vocalist’s “first and last heroin experience”, stripping naked in a restaurant, and throwing bricks over the Berlin Wall to try to set off the landmines. “It was fun,” he says. “In Berlin, nobody knew who we were and we could do anything we liked. And I sampled it all.”

So much hard work and fun was had that three months after starting work at Hansa, Rothery claims that Marillion had all “aged about five years”. In the meantime, EMI were asking about singles.

“EMI were gonna get what they got,” says Fish emphatically. “They gave us no guidance whatsoever. They sent A&R guys down to listen, but we’d just shove them in a room, get them pissed and give them a couple of doobies.”

“One guy got so pissed he fell asleep during the playback,” laughs Kelly. “But at the end of it, he said, ‘Is that all you got?’”

The only other new song they had was Lady Nina, which had nothing to do with the concept. “We played him that, and he said, ‘Oh, that’ll be the single,’ Kelly adds. “And we said, ‘No.’ So he went back to the UK, convinced there were no singles.”

Marillion were aware they had to release something, and finally agreed on Kayleigh, with Lady Nina on the flip. “But Kayleigh was seen as the best of a bad bunch,” says Kelly. “Nobody believed it was going to be a hit.”

According to Chris Kimsey, the single was first mixed at Abbey Road and the master sent to Berlin for approval. Kimsey took the tape back to his apartment. “And it sounded awful,” he sighs. “There was one of those 80s ghetto blasters in the kitchen. I put the tape in and lay there with my head between the speakers, making notes on how I could improve it. Then I went to the studio the next day and put it all into practice. I insisted that we mixed the whole album in Berlin.”

EMI also needed a video to go with the single. In a wonderful twist, the promo for Kayleigh, a song about Fish’s ex-girlfriend, would star German model Tamara Nowy, the woman who would later become his first wife.

Fish had met Tamara on a night out in Berlin and was looking for an excuse to spend more time with her. However, the rest of Marillion vetoed the idea of having her in the video and chose two other models instead. One broke her ankle and the other contracted food poisoning just before the shoot. “So it was a case of, ‘Wanna be in a video, love?’” Fish chuckles.

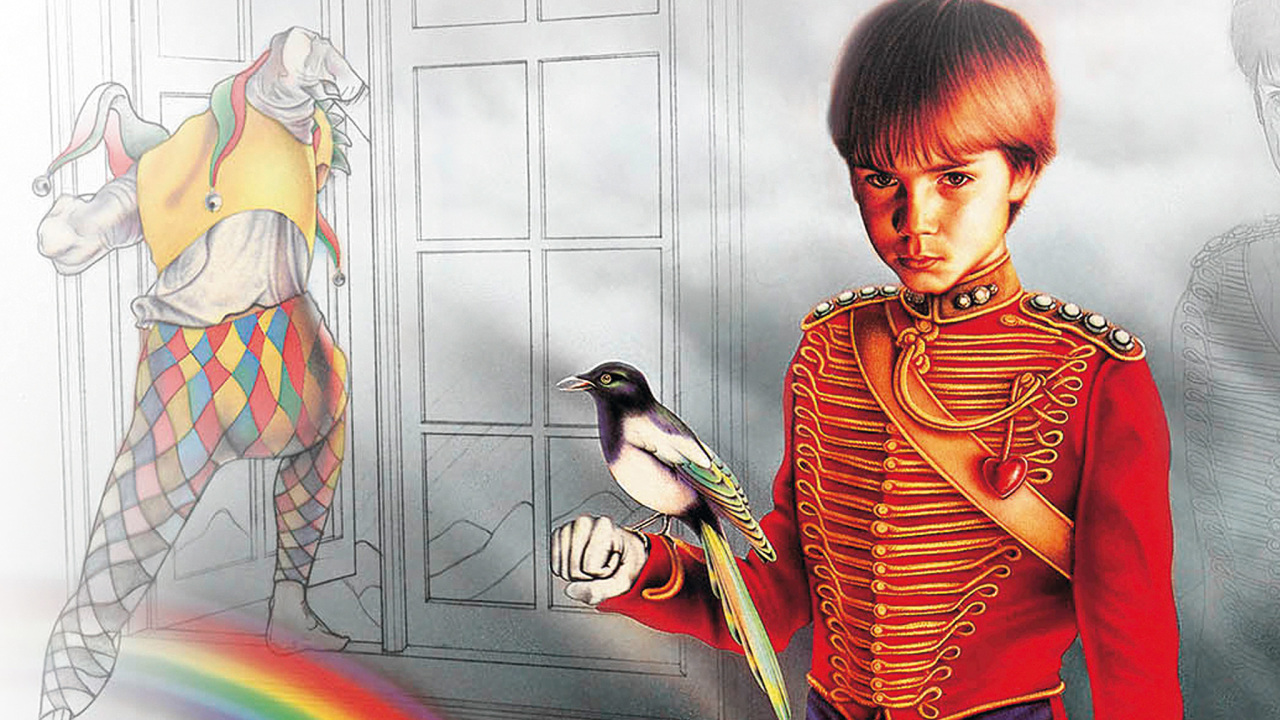

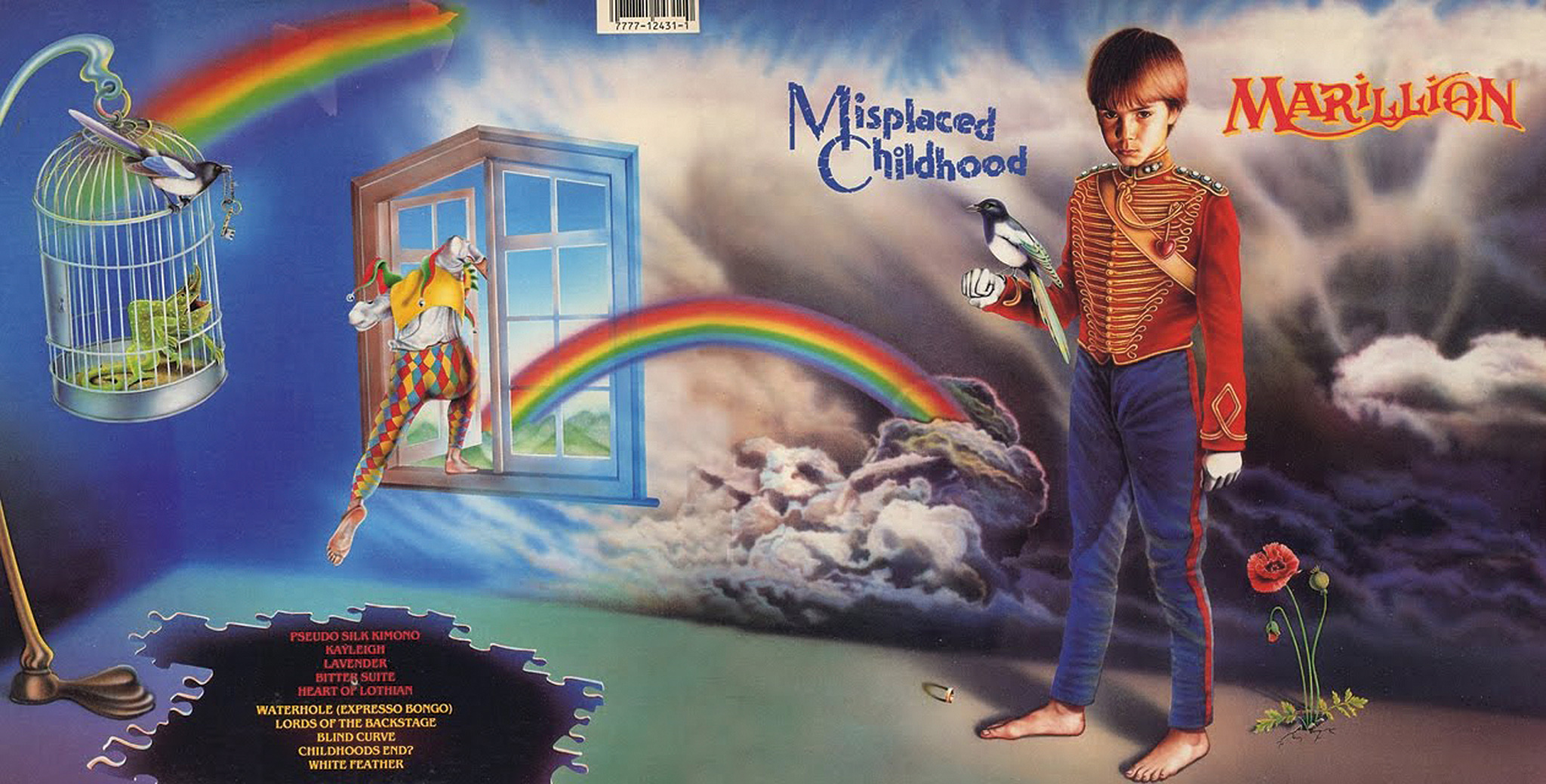

As well as shots of the couple mooching around Berlin, gazing longingly at each other, the promo featured 10-year-old Robert Mead, the ‘drummer boy’ in designer Mark Wilkinson’s Misplaced Childhood cover art. The image was, says Fish, inspired by another supernatural encounter: “Kay used to live in Earls Court and there was a staircase leading up to her flat, and she thought she glimpsed a young boy there one night, just a presence.”

Growing up, Fish was fascinated by military history, and the drummer boy’s uniform would be adapted for his next stage costume: “Mine was rather tight though,” says Fish, “’cos they didn’t do military jackets in double XL sizes.”

Released on April 7, 1985, Kayleigh changed Marillion’s lives forever. For the first time, one of their singles was played on daytime radio, and heard by people other than those who bought Sounds and listened to Radio One’s Friday Rock Show.

It wasn’t hard to fathom Kayleigh’s appeal over Marillion’s previous singles Assassing or Punch And Judy: it was a universal love song. Better still, says Kimsey, “Steve’s opening guitar riff sounded so good on the radio.”

But it was Marillion’s Wogan performance that really sealed the deal. “Before that, we held the record for being the band who did Top Of The Pops the most times and saw their single go down the charts,” says Rothery. “With Kayleigh, we were flown back from Europe on a Learjet just to play on Top Of The Pops.”

Inevitably, the question everyone wanted answered, though, was: who is Kayleigh? “The Sun went looking for her,” recalls Kelly. “But Kay was a very private person so we all had to keep quiet.”

Misplaced Childhood was released on June 17 and compounded the single’s success, eventually reaching No.1. Within a year it had sold 1.5 million copies and gone platinum. “And journalists who’d said we were a bunch of Genesis copyists suddenly went, ‘Oh, this is a happening band,” adds Fish.

Listening to Misplaced Childhood now, Fish’s rather portentous narration on album opener Pseudo Silk Kimono and the Brief Encounter section of Bitter Suite sound like a hangover from the earlier albums, and, however much they resent the ‘Genesis copyist’ tag, there are still familiar echoes all over the record. But ultimately, Marillion had streamlined their sound and become more accessible. As Fish admits, “I’d started to move away from that forced falsetto. I was finding my real voice.”

Furthermore, this wasn’t the woolly, Tolkien-esque Marillion of Grendel ‘and his mossy home beneath the stagnant mere.’ For the most part, Misplaced Childhood addressed real life and real emotions. It was a bigger hit than previous albums Fugazi and Script For A Jester’s Tear because it spoke to more people.

Despite their earlier misgivings, Kayleigh was followed by second Top 5 hit, Lavender, in September. A third single, the Burns Night-meets-rock anthem Heart Of Lothian, followed two months later.

Marillion spent most of 1985 and ’86 on tour, playing the new album in full every night. In America, they opened for Rush and were confronted by “a sea of people going, ‘What the fuck is this?’” laughs Fish. In Britain, it was a different story. On stage, Fish performed without his usual face make-up, as if he was showing his true self. The mainstream music press and daily papers now flocked to talk to Marillion’s outspoken Scottish frontman. “And it rocked the band,” he says. “Because so much of the focus was now on me and I was the one with the biggest profile.”

“Fish seemed to want that more and more,” says Rothery, who admits that Marillion’s brush with “proper fame” made him uncomfortable: “I didn’t like that feeling of never being able to relax.”

Fish, however, had no such misgivings: “When I was a teenager dreaming about being in a rock band,” he says, “this was how I imagined it would be.”

“Fish craved that celebrity,” concurs the guitarist, “and that was part of the conflict that eventually developed between us. He loved a drink and he loved to party. And some people in the band partied too hard.”

By the time Marillion started work on a follow-up album, the cracks were showing. Clutching At Straws, released in 1987, would be Fish’s last with the band. Making it was not a happy experience. “I had a lot to deal with on a personal and professional level, including my ego,” he admits. “I floated off into my own anal world and was a bit of an asshole.”

Rothery laughs when he hears this. “Listen, I took myself far too seriously at that time too. I was all about the music and the art, man.” Tellingly, when asked what he thinks of Misplaced Childhood now, Rothery says he’s proud of it, but that “it represents the calm before the storm”.

In 2005, Fish performed Misplaced Childhood in full on his Return To Childhood tour. To mark its 30th anniversary, he plans to do the same at dates around the country, including the Cropredy Festival in August. But he would have liked to play it one last time with Marillion.

“It would have been lovely,” he sighs. “But it’s 30 years old, for fuck’s sake, so we’d have to drop it down for my voice, and Steve’s gone public and said he won’t change keys.” He pauses, sounding a little exasperated. “But who gives a fuck what key it’s in?”

Marillion clearly do, and transposing the songs to suit Fish is not something they’re comfortable with. “If he can’t sing in the same key as on the album, then we can’t play the same music as on the album,” says Rothery. “You’re not giving people the same experience. It’s better to leave them with the memory.”

For Fish, though, Misplaced Childhood is full of deeply personal memories. On the Return To Childhood tour in 2005, the singer met up again with his old flame Kay. “She came to Edinburgh and I gave her a copy of the album, and she wrote back to say that she cried all the way through.” He hesitates. “I always said I would never talk about her… but she was a pharmacist who worked at Stoke Mandeville Hospital. We’d been emailing each other back and forth, talking about our kids… and one day she told me she’d been diagnosed. Then she went off the radar.”

Not long after, he learned ‘Kayleigh’ had died of cancer. “Her friends told me that in the later part of her life, she let it be known that the song was about her.”

Thirty years on, in 2015, songs from Misplaced Childhood still feature in Marillion’s set. “Out of all the albums we’ve done, there are a few I would rather not listen to again,” says Kelly. “Misplaced Childhood isn’t one of them. It still stands up today.”

That said, having made more albums with vocalist Steve Hogarth than they did with Fish, Marillion don’t dwell as much on the past. Fish, though, is allowing himself one last wallow in nostalgia. “Misplaced Childhood was a crucial album for me and Marillion,” he says, “and I wouldn’t change a thing about it. So I wanted to go out and do it one last time.”

By celebrating its 30th birthday, Fish is paying one last tribute to the people and places that inspired Misplaced Childhood – and, you suspect, finally closing the door on the past.

In the end I ran out of time…

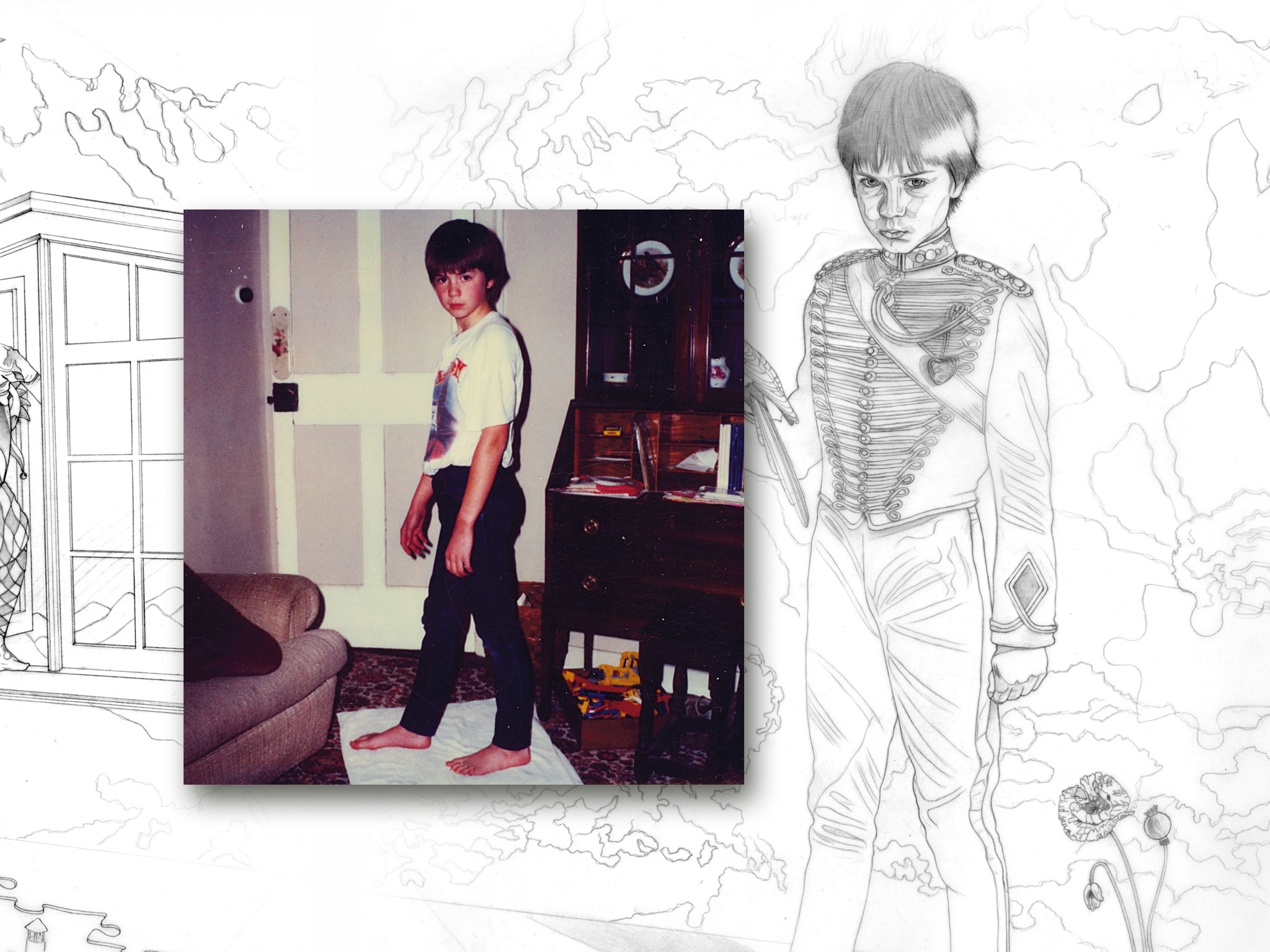

Cover artist Mark Wilkinson, famed for his work with Fish-era Marillion, explains how the Misplaced Childhood album cover came about.

Mark Wilkinson still recalls his reaction to being told about Marillion’s plans for Misplaced Childhood.

“This was the mid-80s, and here they were talking about doing a concept album! I really did think they were gonna be slaughtered by the media, and it would be a commercial disaster. Shows how much I knew!”

The idea for the cover was developed during a series of meetings between the band and artist.

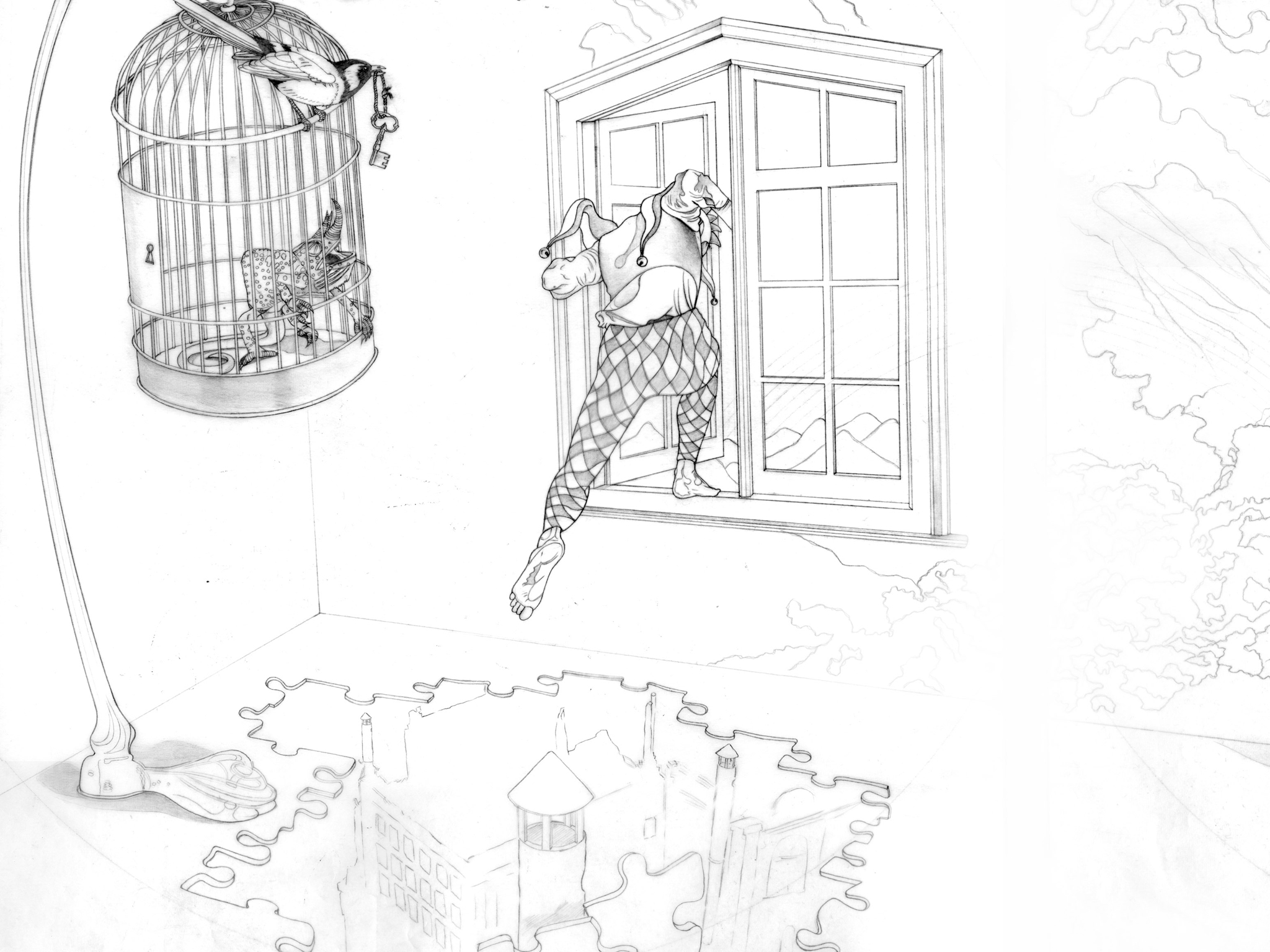

“Fish saw this as the last part of a trilogy, which had begun with Script For A Jester’s Tear. Although I still can’t work out why he saw it that way. But what he was adamant about was that it should be the last time we see the jester on a Marillion cover. So, I took him

by his word and that’s why you see the jester figure literally leaving through the window on the back cover.

“From the start, it was decided that the there should be a boy on the front, dressed in a uniform. I had this image in my head of Emil Sinclair, the boy who was the main character in Herman Hesse’s novel Demian: The Story Of Emil Sinclair’s Youth; he seemed to carry the mark of Cain. But I had a problem finding a model to pose for it.”

However, Wilkinson found the right person on his doorstep. Or, rather, in his local pub.

“Robert Mead was one of the landlord’s sons, who was 10 at the time, and I saw him standing behind the bar one day, and I just thought he had the right personality and look for what was needed on the cover.”

Mead is portrayed with bare feet, something that Wilkinson acknowledges nodded towards The Beatles and their Abbey Road sleeve.

“Paul McCartney was, of course, shot in bare feet, which generated so many crazy theories. And I referenced this here. I was also thinking of David Hockney, who used to put socks on his models, because he couldn’t paint feet! It was my way of saying that feet are important.

“I began by painting Robert’s eyes, then did the rest of his face, and I also spent ages over the uniform he’s wearing. Too long, in fact.”

There’s a lot of symbolism in the cover’s other images.

“The poppy was also used on the Fugazi cover, and it is of course a symbol of death, which Fish thought was important. The rainbow and magpies are a reference to a line from the song Childhood’s End? – ‘And I saw a magpie in the rainbow, the rain had gone’. But if you know the old nursery rhyme, one magpie means sorrow, whereas two means joy. Which is why there are two magpies.”

There’s also a mysterious gap on the back cover, into which the song titles were inserted. But this was left for no other reason than Wilkinson running out of time.

“The jigsaw shaped blank wasn’t supposed to be there. I did intend to fill it in, but literally ran out of time. That was always happening to me.” MD

Steve Hogarth on singing songs from Misplaced Childhood.

“I’d never heard Misplaced Childhood before I joined Marillion. I’d heard Kayleigh and Lavender on the radio, but that was it. In some ways, I still haven’t heard the album. But I have discovered it one track at a time. Every now and again, one of the boys would say, ‘Fancy having a crack at this one?’ and I’d listen to the track with a view to it going in the live show. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t.

“There are facets of Fish’s songwriting and performance that are very angry, and quite violent. And I’m not an angry and violent performer. I’m capable if it, but I can’t summon it up on someone else’s behalf. I’m not a performing dog. So there are songs from the Fish era that I can’t do.

“At the same time, I think Fish has written some great stuff and Kayleigh is a great lyric. Lines like ‘dancing in stilettos in the snow’ and ‘loving on the floor in Belsize Park’ are obviously about very real things and very real memories. And I can latch on to that. I can feel those feelings. It’s got to sit in me like a real thing.

“Heart Of Lothian is a bit weird because I’m plainly not from Edinburgh. But I enjoy singing it. We don’t do it that often, but we do when we’re north of the border, as a mark of respect.

“So when it comes to these songs, my attitude is: if it’s honest enough and true enough and not too gothic or angry or drug addled, then I can get in to it… and I can even get into it if it’s drug addled, as long as I have the same drugs.” MB