One of the unquestioned pioneers of prog, Chris Squire made his live debut in 1964 with The Selfs. Before this, he’d sung in the church choir, having joined it at the age of six. But it was the emergence of The Beatles that persuaded Squire to take music seriously as a potential career. He took bass lessons and got his first cheap model soon afterwards.

However, it was being suspended from school for having long hair that led to him first playing his trademark Rickenbacker. Instead of getting a haircut, he quit school, got a job at a central London music shop and saved up enough to buy the aforementioned bass.

The Selfs were an R&B band but a succession of line-up changes led to a change of name and musical approach. They became The Syn and started to play in a more psychedelic style. A residency at The Marquee Club in London, plus two singles for the Deram label, gave Squire his chance to develop as a bassist, citing the likes of Jack Bruce, John Entwistle and Larry Graham as influences.

When The Syn broke up, Squire joined Mabel Greer’s Toyshop at the start of 1968. They featured Clive Bayley on guitar, who has fond memories of his one-time bandmate’s talent.

“Chris was very impressive, and quickly developed his own style,” Bayley says. “It took him a while to find out how good he could be, but you could always tell he was destined to go on to great things. Unfortunately, not with this band.”

Later in ’68, Squire met Jon Anderson, who had been fronting a band called The Gun. They discovered a mutual love of music and decided to form Yes. Squire said of the decision: “We wanted to help develop each other’s individual styles.”

Filling out the first line-up were guitarist Peter Banks, keyboard player Tony Kaye and drummer Bill Bruford. And on August 4, 1968, Yes played their first gig together, at a youth camp in East Mersea, Essex. This began the most important and long-running musical relationship of Squire’s career. He was the only musician to have been in every line-up of the band, and to appear on all their albums.

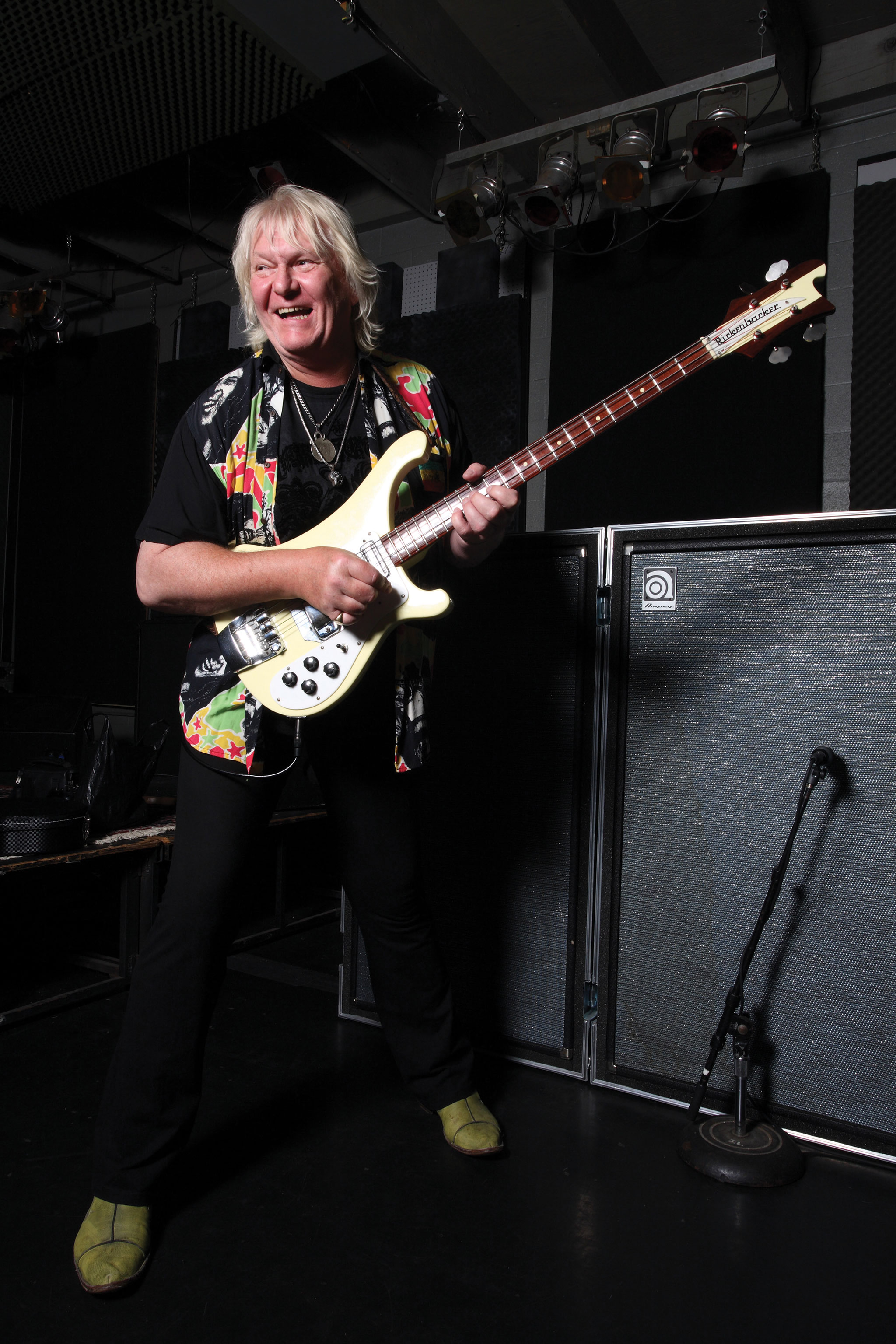

Above: photo by Barry Plummer.

After releasing two albums, Banks was replaced by Steve Howe, and by August 1971, Rick Wakeman had come in to take over from Kaye. This line‑up created both Fragile and Close To The Edge, before Alan White replaced Bruford. Throughout, Squire’s bass playing was paramount to the core of the band’s growing success. He co-wrote a lot of Yes’ music with Howe, and aside from his prodigious bass playing, he also provided backing vocals, which helped give the band’s sound its own timbre and originality.

In November 1974, Yes released the Relayer album, which featured the recently recruited Patrick Moraz on keyboards. But it also signalled a brief break in the band’s career as every member went out on their own, in the process each making a solo album. In Squire’s case, it was Fish Out Of Water, released in 1975. The title was a play on Squire’s nickname of ‘Fish’, and the album showcased his many talents – he not only played bass but also guitar and even drums on one track. He also provided all lead vocals, proving to have a strong, consistent voice.

Fish Out Of Water did well enough to chart both in the UK and the States, aided by the presence of a Yes connection through Bruford and Moraz, as well as Squire’s one-time Selfs/Syn chum Andrew Pryce Jackman on keyboards.

Yet despite the generally positive reaction, Squire wouldn’t record a second solo album until 2007, when he put out Chris Squire’s Swiss Choir. Although ostensibly a collection of Christmas tunes, this was actually a little more cunning, in that the traditional songs were developed in surprising ways, reflecting the humour and subtlety of the album’s title. Helped by the likes of Steve Hackett, Squire came up with a collection of songs that was more about having musical fun than exploiting the season of goodwill for commercial reasons.

This isn’t the only Christmas release associated with Squire. In 1981, he teamed up with Yes drummer Alan White to put out Run With The Fox, which is regarded as a credible seasonal single. Jackman was again involved, this time on the orchestration, and the B side – Return Of The Fox – had former King Crimson man Pete Sinfield as one of its writers.

This Squire/White single was released shortly after another project, named XYZ, fell apart. This would have seen the Yes duo teaming up with Jimmy Page. They got as far as writing and even demoing songs, and there was a hope that Robert Plant might also be involved. However, it eventually fell on stony ground.

“We did four songs in demo form,” Squire told Prog. “These are on the internet and show what we might have become if things had developed. A few of the ideas we came up with did end up being used later on Yes albums. For instance, Mind Drive from Keys To Ascension 2. Another, Can You See, we reworked into Can You Imagine for the Magnification album.”

Shortly after XYZ was abandoned, Squire teamed up with Trevor Rabin in a new band called Cinema. Alan White was again involved, and shortly after the project began to take shape, both Tony Kaye and Jon Anderson came on board. It was inevitable that Cinema would be a new version of Yes.

The rapport of this new-look Yes became obvious as they reinvented themselves on the hugely successful 90125 album, in the process attracting a new generation of fans with a sound designed for the modern era.

“We didn’t want to retread old ground,” Squire told Prog. “We saw ourselves as a new band, not a reunion of Yes. And that meant we could take more risks than maybe people expected. But that was the fun of the era – we could enjoy ourselves and almost escape our past, at least on the album.”

Above: Photo by Rex Features.

Squire still found time to work outside the band, as he did in 2000 when he joined occasional Yes member Billy Sherwood in recording an album called Conspiracy. This project actually started out in 1992 as The Chris Squire Experiment. With Alan White on drums, they toured America before other commitments intervened, putting it on the back-burner.

In 1996, Squire and Sherwood announced plans to record an album called Chemistry. However, this was aborted as Yes took priority. Finally, the duo managed to make time to record and release Conspiracy, which featured all the songs originally planned for Chemistry, including two that had already been used on the 1997 Yes album Open Your Eyes, namely the title track and Man In The Moon.

Squire and Sherwood eventually adopted the name Conspiracy for the band, releasing an album titled The Unknown in 2003. A live line-up was subsequently assembled for a 2004 tour, but the planned concerts never actually happened, with Conspiracy only playing one show. At least this was filmed and released as the Conspiracy Live DVD in 2006.

In 2012, Squire teamed up with Steve Hackett in Squackett. The duo released the album A Life Within A Day, and the title track picked up the Anthem Award at the 2012 Progressive Music Awards.

“I just think it’s another aspect of what I do,” Squire said at the time. “There was no pressure. We had no deadlines or any tours or anything lined up. It was an easy way of working on this material.”

“Chris was the king of the bass and remains an eternal inspiration,” says Hackett. “He was full of life and really fun to be with.”

Both Squire and Hackett hoped there would be an opportunity for Squackett to tour, and they also intended to do a second album, but their schedules were so busy that A Life Within A Day turned out to be a one-off release from the pair. However, they did hook up one last time, when Squire guested on the 2015 Hackett solo album Wolflight. He played bass on the track Love Song To A Vampire. As it turned out, this was the last recording session in which Squire would participate.

“During the Wolflight sessions towards the end of last year, I was working on Love Song To A Vampire with [keyboard player] Roger King,” Hackett explains about Squire’s involvement. “Chris was visiting the UK at that time and had a couple of spare days. He asked me if there was anything I’d like him to play on. It was perfect timing as I’d reached the point of needing a bass part on it.

“We recorded in my Twickenham studio, where he borrowed my Fender Precision, which hadn’t come out of its case for some time. It was as if it had been lying dormant in its coffin for practically 20 years, but it immediately sprang back to life in his hands. His incredible tone thundered like a lead line as he wove around the other parts with his distinctive sound for both the chorus and the denouement. He added something magical to the song.”

In 2004, Squire was part of The Syn reunion, which led to the release of the album Syndestructible a year later. This reformation was short-lived, though, with the band splitting up soon afterwards.

Chris was the king of the bass and remains an eternal inspiration. He was full of life and really fun to be with.

Over the years, Squire also guested on a number of other albums. These included Rick Wakeman’s The Six Wives Of Henry VIII and Criminal Record, The Buggles’ Adventures In Modern Recording, World Trade’s Euphoria and Gov’t Mule’s The Deep End, Volume 2. He also helped out Billy Sherwood on his Prog Collective projects, working on the albums The Technical Divide and Epilogue.

But, of course, the commitment to Yes took up most of Squire’s time. Despite regular changes in the band’s line-up, the bassist remained a constant, and as such became the de facto leader, the man who understood better than anyone what everyone expected from Yes.

“His attention to the minutest details of the music was immense,” recalled keyboard player Geoff Downes. “You certainly couldn’t get away with playing anything out of line. He’d come over with his inimitable casual fashion and point out, ‘That’s not quite right.’”

Squire’s active career spanned half a century, during which time he became one of progressive music’s most crucial spirits. The number of classic recordings in which he was involved is a testament to his legacy.

Photo below by NEIL ZLOZOWER.