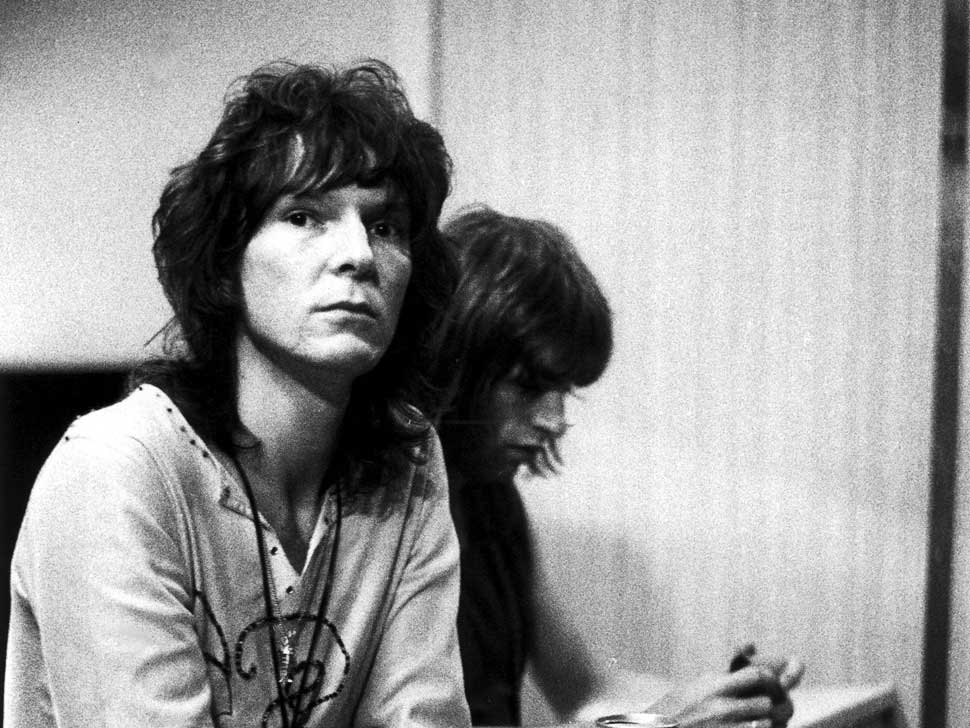

Part of a generation of players who paid their dues through the ‘50s and early ‘60s, if not exactly leading the charge of the psychedelic brigade, The Syn and later, Mabel Greer’s Toyshop, were part of the infantry slogging their way around the clubs of London and the provinces at precisely the point at which pop and rock started to experiment; something which Chris Squire, if you’ll forgive the expression, took to like a fish to water by the time Yes were underway.

Though the Rickenbacker bass could never be considered a small guitar, against Squire’s formidable height and frame it seemed tiny. However, the sound he extracted from those four strings bordered on the monumental. With a self-assurance that steadily grew from Yes’s 1969 self-titled debut, Squire’s brand of bass playing wasn’t content to merely fill in the root notes or light and shade via a passing phrase.

Under his agile fingers there were no parts of song that he regarded as being out of bounds, or which he thought might not benefit from his application of unconventional harmonies, rhythmic counterpunches or his melodic capabilities. Adept at switching from a thunderous growling support to expressive, loquacious lead lines, often within the same composition, Squire was a bassist who took risks rather than simply make do.

That fiery inventiveness helped Squire liberate the bass guitar from its traditional back line role of sharing the heavy lifting in the rhythm section, and repositioned it, when required, as an instrument capable of delicate and nuanced articulation. Blessed with brains and brawn, that presence and drive were a cornerstone upon which Yes’ success was ultimately built and maintained.

It’s staggering to think that the surging bass lines that provided the high octane fuel propelling Yours Is No Disgrace and the bold leaps setting-up Steve Howe’s exultant solo at the end of Starship Trooper sprang from the fertile imagination of a young man just 22 years old when Yes recorded The Yes Album in the Autumn of 1970.

More than that though, Chris Squire, even at that stage, had acquired a signature sound which made him stand out from the crowd, It’s something that most, if not all, musicians aspire to but which very few ever achieve.

If you heard those rasping, galloping metal-rimed notes you knew it couldn’t be anyone else. Always assertive, sometimes reckless, sometimes inordinately showy, it didn’t just come from the type of string he used, or a make of amplifier, or the twist of the treble pot on his guitar. That trademark tone, and the attitude it embodied and expressed, came from deep within the man himself.

His Rickenbacker bass sounded, more often than not, like it could blow a hole in the wall, and with a voice that when meshed in harmony with his band mates, sounded like it could charm the angels down from heaven. Those two seemingly contradictory elements made Chris Squire a force to be reckoned with.

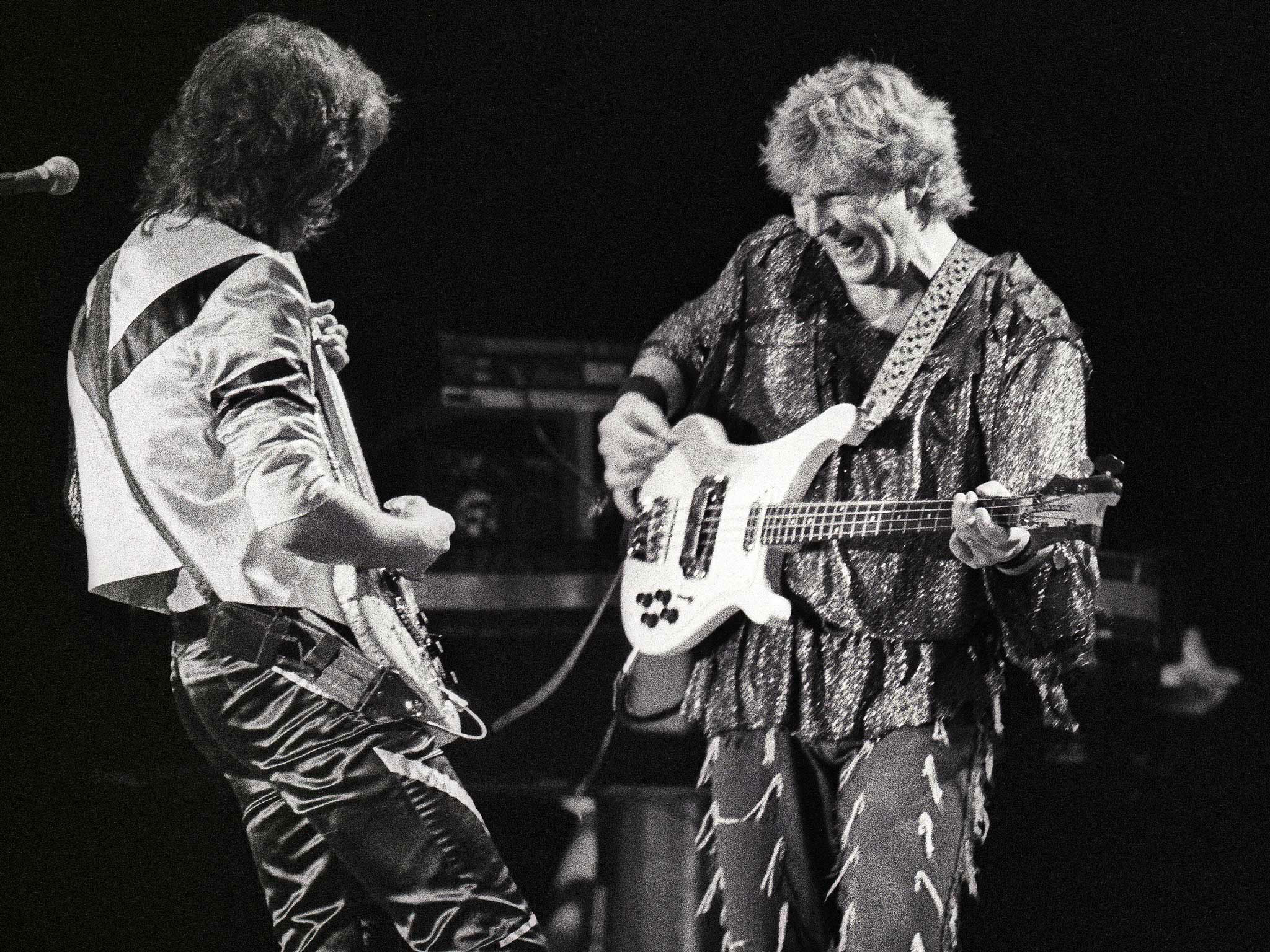

The phenomenal success which Yes received following Fragile, Close To The Edge and Relayer put them into the premier league of rock stars and with it, the extravagant lifestyle of Rolls Royces, fine wines, and other flummeries which Squire enthusiastically embraced.

Laconic in the extreme, there are numerous accounts threaded throughout the history and chronicles of Yes of Squire keeping his band mates hanging around, a personality trait that occasioned irritation and frustration. Similarly, his habit of slowly deliberating a potential course of action, or the efficacy of one mix over another led to what might be benignly referred by some as “creative tension” but which others regard (off the record) as “fucking infuriating”.

By his own admission he could be obstinate and periodically bloody-minded. Sometimes viewed as possessing a degree of ruthlessness, his determination to keep Yes on the road as a working entity showed how tenacious he was. The decision to carry on working without Jon Anderson in 1980, and especially in 2008, following the singer’s respiratory illness, caused controversy and bad blood within the group and fandom.

Yet away from the cut and thrust of internecine politics, the man played like a dream. For all that ferocity, firepower and huge muscularity that pushed and knotted Yes’s ambitions together into a cohesive and unstoppable proposition, he also incorporated a wonderful economy that kept things simple and true. Outside of Yes, 1975’s Fish Out Of Water, arguably the most consistent of Yes member’s solo albums, counts a high watermark in an already overcrowded and brilliant back catalogue, as was the criminally underrated 2005 side project, Syndestructible by an updated line-up of his old band The Syn.

But it’s with Yes that he’ll be remembered. Sometimes when he was strutting about the stage he could look like a bit of a bruiser. Thrusting his bass about the place, he might be about to pick a fight as pluck a string. Belligerent and willfully mercurial, he’d scowl one moment and flash a grin the next. But if you got close enough you’d see a twinkle in his eye. He loved being where he was, being on stage reveling in the acclaim, always playing to the crowd.

Talking to him over the telephone when writing the liner notes for the 5.1 surround sound edition of Close To The Edge, I asked how he felt after completing such an ambitious record. “I remember thinking…” there was a pause as he cast his mind back to 1972. It was a very long pause. For a moment I thought the line had been lost. “I remember thinking… we’d done a good job”, he said in the midst of a short gurgling laugh.

A good job doesn’t even begin to cover it. Chris Squire and the music he helped create has been a part of our lives for so long. That’s why we feel his passing so keenly. The news of his death coming so quickly after his diagnosis in May compounds the sense of shock which so many have expressed around the world. While Progressive music has lost a unique voice he leaves behind a truly remarkable legacy for which we are thankful.