We love to attach honorary titles to musicians. Especially those who define a genre: The King Of Rock’n’Roll. The Queen Of The Blues. The Godfather Of Soul. And certainly, Chuck Berry, who died on March 18 at age 90, earned every designation thrown his way: The Poet Laureate, The Father, The Inventor, or as Bob Dylan called him, “The Shakespeare of rock’n’roll.” But really, Berry’s gifts made him much bigger than any one title would cover.

As a chief architect of 1950s’ rock’n’roll he created a joyous model that inspired a never-ending list that includes The Beatles and the Beach Boys, the Stones and Springsteen. He was also the genre’s first electric guitar hero (there’s no better shorthand for rock than the intro to Johnny B. Goode), and its first self-contained singer-songwriter. Either of those accomplishments would be enough to guarantee his legacy. But there’s more.

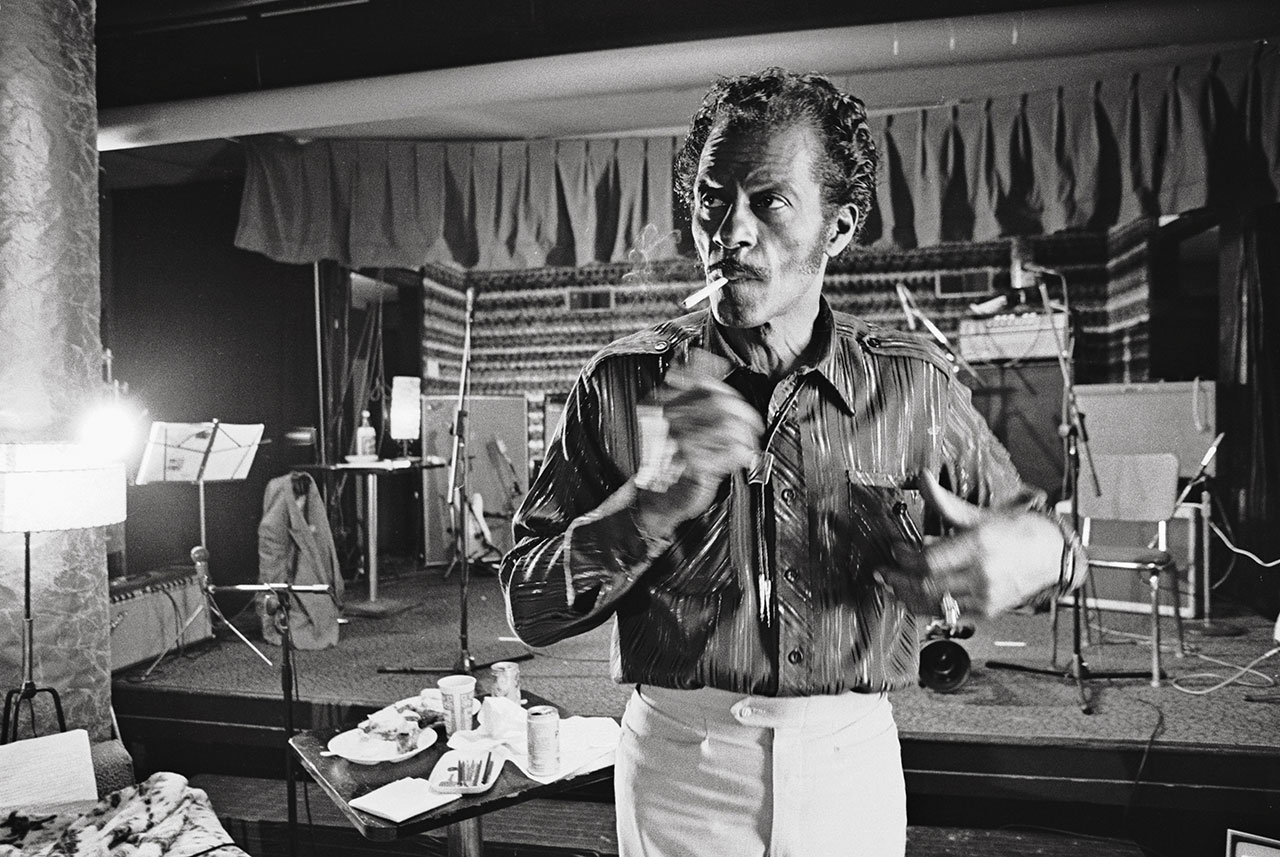

Unusual for the era, Berry was as much a businessman as he was an artist – he opened his own night club early on and managed his own affairs. In interviews he always came back to the almighty dollar. “The dollar dictates what music is written,” he once said. His obsession with money would be part of his eventual undoing, and is probably the main reason why most of the posthumous tributes to him have remained fairly dry-eyed. Yes, he was an amazing showman, a performer whose repertoire of moves became rock’n’roll itself. But he was also a tightwad, a two-time jailbird and a hard-to-love human being.

But really, amid all his complexities, Chuck Berry’s most enduring accomplishment might be as a shaper of our social history. Through his vivid, lyrical story songs, he helped invent, and then mythologise, the teenager.

When you’re talking about Chuck Berry, the teenager is a good place to start. In the USA soon after World War II, what used to be called the young adult or youngster started to gain identity, attitude and pocket money. Here was a new class of citizen – brash, idealistic, energetic, innocent; a noble savage in blue jeans, looking for a hero and language to articulate all their wild hormonal yearnings. On one hand you had Marlon Brando, who when asked in The Wild One what he was rebelling against, replied: “Whaddya got?” On the other you had Chuck Berry, our dashing correspondent in Teensville, waxing poetic.

Consider a few of his classic couplets, and the way they addressed core teen subjects:

Cars

‘As I was motorvatin’ over the hill, I saw Maybellene in a Coup de Ville.’

‘Cadillac rollin’ on the open road, nothin’ outrun my V8 Ford.’

Girls

‘Beautiful Delilah, dressed in the latest style, swingin’ like a pendulum, walkin’ down the aisle.’

School

‘Back in the classroom, open your books, gee but the teacher don’t know how mean she looks.’

Sex

‘We was reelin’ and rockin’, rollin’ to the break of dawn.’

Rock’n’roll

‘My heart’s beatin’ rhythm and my soul keeps a singing the blues/Roll over Beethoven and tell Tchaikovsky the news.’

Of course, Berry wasn’t like most of his audience. He was neither a teenager (he was 28 when Maybellene hit in the US in 1955) nor white. But songs about being black, written in an open-ended way, acted as an allegory for the teenage experience. Or vice versa. ‘Country boy’ to coloured boy; ‘Brown-eyed handsome man’ to brown-skinned handsome man. His songs were full of code. But there was nothing hidden about Berry’s pragmatic intent. In the 1987 documentary Hail! Hail! Rock ’N’ Roll, he told Robbie Robertson: “When I was out on the road, half my audience was teenagers. You play what the people want. Sing about them and they’ll listen to you.”

The rise of the teenager ran parallel with the rise of the music that made Chuck Berry famous. Boogie woogie, blues, R&B, jumpin’ jive – all of these were, as Phil Everly once said, “avenues that fed into main road” that became rock’n’roll. Before he was a teenager himself, Charles Edward Berry, born on October 18, 1926, spent his youth in St. Louis. He was one of six children, and his parents, middle-class and well-educated, encouraged him to pursue artistic interests such as poetry and photography.

In high school Berry got his first guitar, and by the time he’d dropped out he was playing house parties and church functions. But his own teenage years were cut short after he and three friends were arrested for armed robbery. Berry did three years in prison. Afterwards he moved back in with his parents, and pursued careers in carpentry and then hairdressing. But music’s pull was strong, and by the early 1950s he was touring juke joints and roadside bars. In Chicago he met Muddy Waters, who referred him to Leonard Chess and his record company. In 1955 Chess Records signed Berry.

Right from the first single, Maybellene, it was obvious that Berry was something special. That stuttering guitar intro. And then that opening line, which found him already adding to the English language with the word ‘motorvatin’. Where did Chuck’s sound come from?

“I wanted to sing like Nat Cole, with lyrics like Louis Jordan, with the swing of Benny Goodman, with guitar like Carl Hogan, and the soul of Muddy Waters,” Berry told US chat-show host Johnny Carson in 1986. “But Louis Jordan was the main guy for me.” Indeed Berry’s most famous guitar intro, that sliding double-stop lick on Johnny B. Goode, was borrowed straight from Carl Hogan on the Jordan song Ain’t That Just Like A Woman. It’s a shame that Jordan isn’t better remembered today. The sax-playing singer and his combo the Tympani 5 ruled what was then called the ‘race’ charts and hit parade in the late 1940s with songs such as Ain’t Nobody Here But Us Chickens and Is You Is Or Is You Ain’t My Baby? Funny, sexy, swingin’, all of those sound like blueprints for rock’n’roll. Just replace the alto sax with an electric guitar and bingo. Which is basically what Berry did.

Between 1955 and ’59, Berry ruled the charts, with an amazing run of songs that built the ground floor of rock: School Days, Rock ‘n’ Roll Music, Roll Over Beethoven, Too Much Monkey Business, Carol, Sweet Little Sixteen, Memphis TN, Little Queenie, Back In The USA. When asked about his songwriting methods early on, Berry said: “I concentrate on the lyrics, usually, and then I work out the song on my guitar when I have the lyrics on paper. Then I tape it to get an idea of the overall sound, after which I record it. Most of my songs come from either personal experience or other people’s experiences or from ideas I get from watching people. I would say that I aim specifically to entertain and make people happy with my music, which is why I try to put as much humour into my lyrics as possible.”

This answer doesn’t capture how remarkable Berry’s lyrics are. The economy, the well-chosen detail, the sheer motion of them. It’s almost as if the words themselves have gears attached that are propelling them forward. For one of countless examples, take this line from Jaguar And Thunderbird: ‘Ten miles stretch on an Indiana road, t’was a sky blue Jaguar and a Thunderbird Ford/Jaguar setting on ninety nine, tryin’ to beat the Bird to the county line.’

Even when you recite it, it feels like it’s moving of its own accord.

It wasn’t all cars and girls either. Havana Moon was like a novella about long-distance separation, while You Never Can Tell tweaked the generation gap with a wink and a French accent. Whatever he wrote about, Berry brought it to three-dimensional life in a way that was eons ahead of his contemporaries. Berry rightly wanted every word heard: “I think my success had a lot to do with my diction. The pop fan could understand what I was saying better than many other singers.”

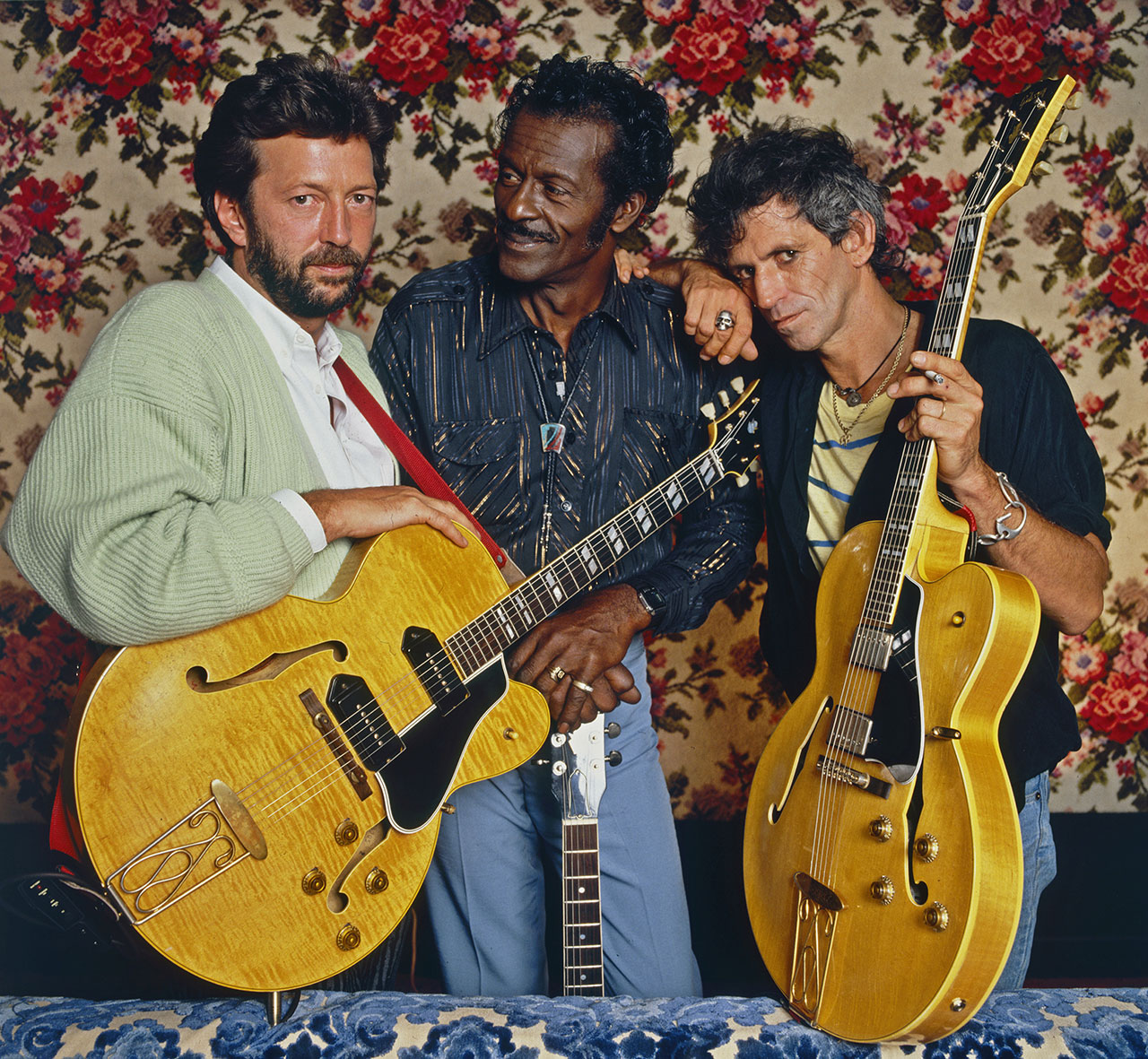

As if being one of the greatest lyricists of the 20th century wasn’t enough, there was also Berry’s guitar playing: lean, mean, immediately recognisable. As Keith Richards put it: “Chuck Berry always was the epitome of rhythm and blues playing, rock and roll playing. It was beautiful, effortless, and his timing was perfection. He is rhythm supreme.”

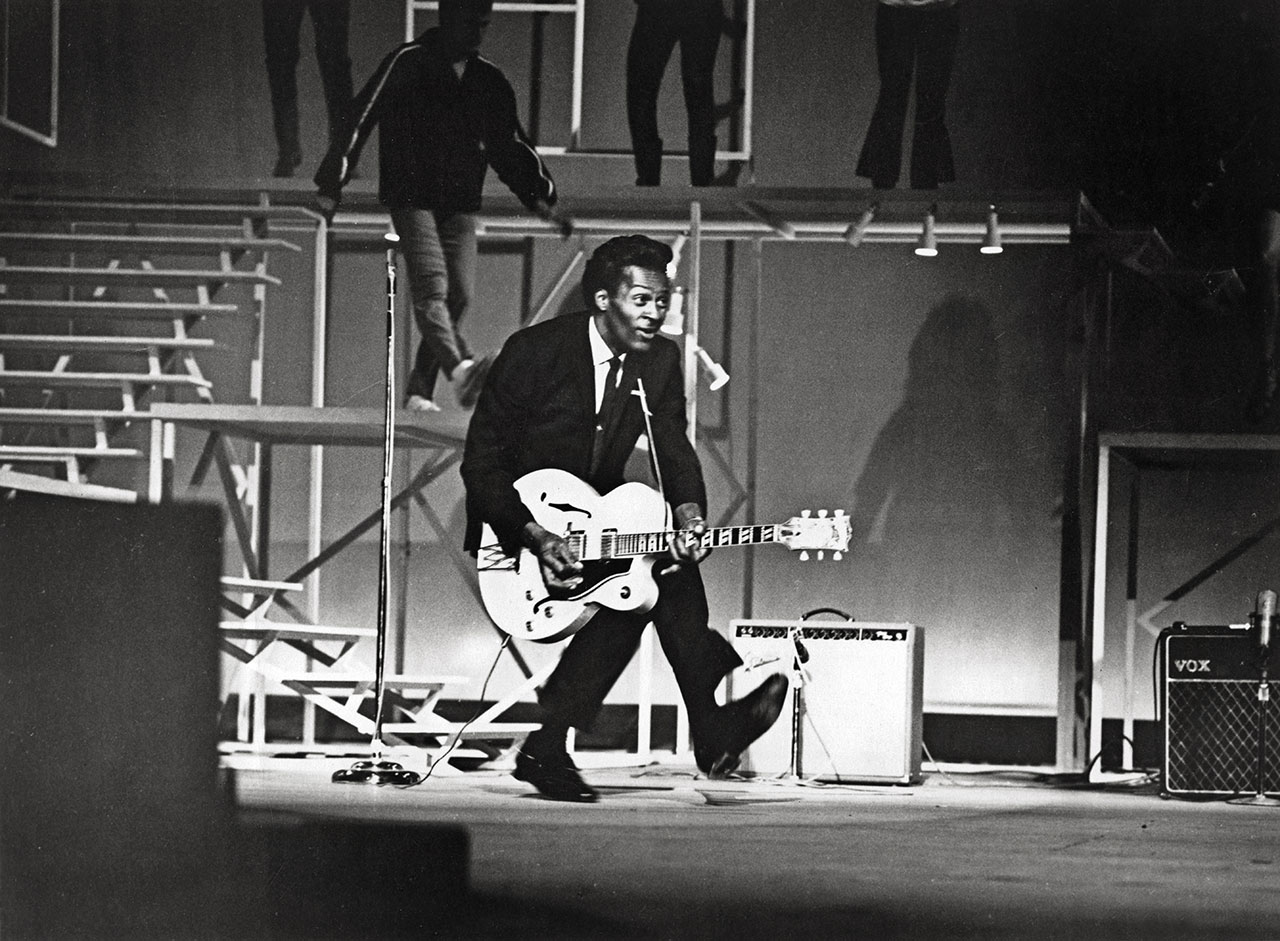

The splits and kick-struts that accompanied Berry’s playing added gymnastic glamour. He came up with his most famous move, the duck walk, one night in 1956, when he was trying to hide the wrinkles in a seersucker suit he’d been wearing for too many consecutive shows. When he did it during his performance of You Can’t Catch Me in the Alan Freed film Rock Rock Rock it became an international trademark.

The rock’n’roll blitz of the late 50s was famously cut short via abrupt exits by its heroes; Elvis went in the Army. Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran and Richie Valens went in crashes. Jerry Lee Lewis went in disgrace. Little Richard went to church. And Chuck Berry went to prison.

During a tour in 1959, Berry and his band stopped in Juarez, Mexico. After hitting a few strip clubs, they had lunch at a local cantina, where Berry flirted with a girl at the next table. Janice Escalante was a full-blooded Apache Indian and a 14-year-old runaway. She told Berry she was 21. On a whim, he invited her to work as a hostess at his nightclub back in St. Louis; his idea was that she would dress in Pocahantas-style garb. When they arrived in St. Louis, Escalante started hostessing at Club Bandstand. A few weeks later, while Berry was back on the road he heard that she had stopped going to work. Worse, the local police had been asking to speak to him regarding a teenage employee of his who’d been arrested for prostitution.

After two separate hearings – what Berry called “the Indian trials” – he was fined $10,000 and sentenced to three years in prison. For years Berry denied the incident. But in his 1987 autobiography he recast his jail time as a time of self-improvement. “I spent all of my off-duty time studying business management, business law, accounting…”

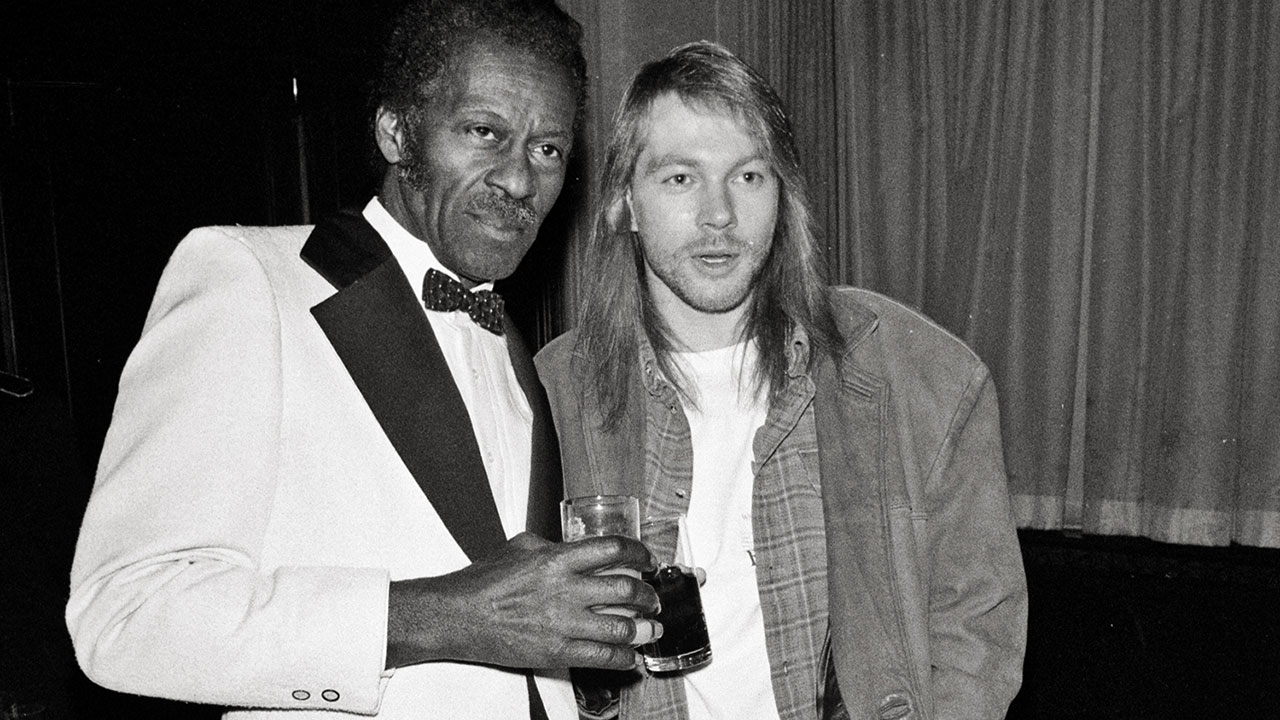

Berry’s return to music in 1964 was accompanied by a flurry of great new songs, among them No Particular Place To Go, Nadine and You Never Can Tell. But in his absence, the British had invaded, selling his sound back to America and changing everything. As with the Everly Brothers, Roy Orbison, Gene Vincent and other old-guard rockers who’d survived, Berry never regained his momentum. And like those artists he found his most enthusiastic audience in the UK.

For all of his classic songs, his sole No.1 chart hit came in 1972 with the double-entendre-laced My Ding-A-Ling. Not only was its sophomoric tone beneath Berry, but also it wasn’t even original – he basically rewrote a 1952 song by New Orleans musician Dave Bartholomew.

A new generation’s introduction to Berry came through the Hail! Hail! Rock ’N’ Roll documentary. Legends are entitled to attitude, but Berry was a terror, running everyone involved through the ringer, from director Taylor Hackford (“When you deal with Chuck, there is conflict”) to musical director Keith Richards (“He gave me more headaches than Mick Jagger”). Petulant outbursts, heated debates about arrangements, sloppy guitar playing, and his acolyte Richards taking the brunt of his ego and attitude while trying to keep the whole show together.

“Keith Richards didn’t have a problem with me, but I certainly had my problems with him,” Berry said two years later. “Keith has a lot of problems. Actually, I don’t think that film is so good. They should have done it differently. But what do they know?”

Berry’s thorny side continued to show. A year after the film, while publicising his autobiography on British TV, Berry was asked if he would play his signature tune, Johnny B. Goode. “No. For second-class money you get a second-class song,” he said, and played Memphis, Tennessee instead.

To compound matters furthers, in 1989 Berry had another brush with the law. He was caught secretly videotaping women in the toilet of his restaurant. A former employee took him to court with a lawsuit that alleged the tapes “were created for the improper purpose of the gratification” of Berry’s “sexual fetishes”. Several women followed with similar class-action suits. Berry denied it all. Shortly after the restaurant was closed, the Feds raided his estate. Along with firearms and marijuana, they found a cache of videotapes showing underage girls in sexual poses. This kept Berry in court for more than a year. Charges were finally dropped when the prosecuting attorney became embroiled in his own financial scandal.

The prominent use of You Never Can Tell in Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 film Pulp Fiction helped erase some of the icky residue and lift Berry back into the spotlight. Meanwhile, in semi-retirement, he continued retreading his greatest hits with one-night stands, famously always demanding cash up front. I have several musician friends in Nashville who played with Berry as part of pick-up bands. A typical account comes from Gary Nicholson, a songwriter-guitarist who has written for Bonnie Raitt and Delbert McLinton.

“The promoter that hired us to back up Chuck at the Shreveport municipal auditorium had heard we were the best band in the area,” Nicholson says. “We went over all the songs and waited all day for Chuck, thinking he would rehearse with us in the afternoon. Of course, that didn’t happen. After we played our opening set, Chuck appeared and only said: ‘Watch me’ before we took the stage. All the keys were different from what we thought, and the times I broke out of rhythm to go for any soloing he glared at me and I backed off. We got through the set, and he went out for a solo encore, put his guitar in the case and drove away in a red Cadillac before any of us could even shake his hand.”

As he passed the age of 80, Berry’s guitar and Cadillac went to the Smithsonian, sealing his legend. Meanwhile, he stayed mostly at his St. Louis nightclub Blueberry Hill, where his band consisted of family and friends. In late 2016 he made a surprise announcement that he would be releasing an album, his first in 30 years. Titled simply Chuck and dedicated to Toddy, his wife of 68 years, it comprises mostly new songs. And now it will serve as Berry’s parting statement to the world.

But perhaps a more appropriate – and more eternal – parting statement came 40 years ago, when NASA put on the Voyager 1 space probe a Golden Record full of sights and sounds of our cultural best. As well as Mozart and Beethoven, also on it was Berry’s Johnny B. Goode. Scientist Carl Sagan wrote to Berry: “When they tell you your music will live forever, you can usually be sure they’re exaggerating. But these records will last a billion years or more.”

A week after the Voyager launch, comedian Steve Martin, playing a psychic in a Saturday Night Live sketch, predicted we’d soon get an urgent message from aliens: ‘Send more Chuck Berry’.

Chuck is released on June 16 via Dualtone/Decca