Nightwish man Troy Donockley remembers the very moment that Clannad first made an impression on his music – and his life: “I was 18 years old, confused, in a bikers’ pub listening to a jukebox, and Theme From Harry’s Game stopped me dead in my tracks. I lost all contact with my surroundings. That atmosphere – and Moya Brennan’s voice – was like nothing I’d ever heard.”

Clannad (the name created by contracting ‘Clann as Dobhar’, meaning ‘family from Dore’, not Gaelic for ‘family’ as many believe) broke into the world’s consciousness with that 1982 single, which has more than outlived the TV series it was attached to. As the only UK Number One single in the Irish language, its uniqueness could make it prog in its own right.

The track launched the second of three phases in the Irish family band’s history, all trademarked by soaring close harmonies, traditional and modern instruments, and left-field arrangements. Their career path has entailed kick-starting the stardom of younger sibling Enya, duetting with U2 singer Bono (who bought a hearse and pretended to be dead in the back during the video for In A Lifetime), persuading Steve Perry to appear on the only non-Journey track of his career at that point, and backstage parties with Phil Lynott and Rory Gallagher which no one in the band admits remembering.

More importantly, those three phases all have prog credentials to varying degrees. Although main songwriters Pol and Ciaran Brennan at first claim to be unaware of what prog actually is (possibly a surprised reaction at being approached by this very magazine), they soon open up and those influences become clear.

Siblings Moya, Pol and Ciaran, along with their uncles Noel and Padraig Duggan, had a definite aim with their self-titled debut album, released in 1973. They’d gone around their native Donegal with tape recorders, capturing folk songs before they were forgotten forever. “We had in our minds that we’d make folk albums,” Ciaran recalls. “Some of them didn’t have any pattern or arrangement, so you could wrap anything around them to keep them alive. We were listening to Jethro Tull and jazz rock, and I would have been very influenced by Pentangle.”

Donockley supports Ciaran’s assertion. “Clannad were primarily a prog folk act,” he says. “Structurally, they were very much like Pentangle; the progressive tendencies shine out on albums like Dulaman [1976] and Fuaim [1981]. Check out Strange Day In The Countryside from Crann Ull [1980] – it’s very pastoral hippie-acoustic prog, with its cross-fade from harp to guitars and wordless voices.”

Clannad’s debut saw them immediately embroiled in the kind of artistic battle many prog artists would be familiar with, as they stuck to their guns about singing in the Irish language, fighting label pressure to do otherwise. Ciaran recalls: “We did it in two and a half days after we won a competition in Letterkenny or somewhere. The record label MD said, ‘That’s never selling!’ and sent us back in to translate one of the songs into English. I was a pushy 19-year-old. I told him, ‘You’ll probably get a villa in Spain out of this!’”

He can’t have been far wrong. For Pol, though, it was always about crossing cultural streams. “It’s definite,” he says. “Our background is between the traditional stuff and classical stuff. When we were very young we were all classically trained on piano, and we had voice training and stuff. But we were growing up with the music of the day all around us. In the 60s we were stuck to Radio Caroline and Luxembourg. Ciaran and I listened to a lot of John McLaughlin but we were soaking in everything. I was much more of a rock-head myself. Musically, I was very challenged by it.”

Marillion guitarist Steve Rothery was struck by their unique blend at an early point in his career. “I thought Clannad were a unique blend of Celtic folk with prog elements,” he remembers. “They had a very evocative and ethereal sound. Moya Brennan’s vocal and the band’s harmonies are quite unique.”

The massive success of Harry’s Game brought those elements to global attention and led to a change of direction in the mid-80s, powered more by synths and a sound which could be compared to the neo-prog of the era. It’s first hinted at on 1983’s Magical Ring, of which Donockley says: “It’s an unreserved classic – a masterpiece of spacey prog-folk which is just beautiful. If it’s not already in your record collection, your musical education has amounted to nothing and you are an utter buffoon!”

Pol enthuses over a new era of inspiration: “The influences of bands like Yes, Marillion and fucking anyone – we were eating them up! If you’re looking for prog in our music, look in the riffs.”

He points to the band’s work on another 1980s TV series, Robin Of Sherwood, and particularly the track Scarlet Inside, written for Ray Winstone’s Will Scarlet. “I was rocking out with that. It’s Joe Elliott of Def Leppard’s favourite – he took me for beers and told me so!” he laughs.

Rothery confirms Clannad’s work informed at least the artistic intent of his Wishing Tree side-project. “The blend of the symphonic and acoustic elements of the music, and the odd time signatures of some of the pieces, give them a progressive feel,” he notes. “The mood and atmosphere of their music was one of the influences on the Carnival Of Souls album.”

But Clannad’s most riff-led album is 1987’s Sirius, which saw them fully embracing elements of neo-prog and even pop in a big US-style production. It involved Steve Perry, Bruce Hornsby and JD Souther, and resulted in a record many fans hated – brother Leon Brennan, the band’s tour manager, warns: “If you like Sirius, don’t ever say so in Ireland!” Nevertheless, it contains tracks where synths and different time signatures dominate, including In Search Of A Heart, Second Nature and the title track. Ciaran reflects: “I would agree it’s a prog rock album. I was very glad we took that direction when we could. We’re very comfortable with it now, but at the time there was that backlash. It was very expensive…”

Although they don’t revisit many of its tracks in their live shows, Pol says: “I’ve said to Ciaran it’s the one I’d love to do as a live album. Rock it out, use real strings – do a one-off show. The songs are good. With some of the timings, there’s an element of prog. Some of them are straight, but then that’s the last thing that some of the others are. I think what happened was we didn’t have enough of our own identity on them.”

Donockley is one of those who wasn’t a fan of Sirius: “There was a lot of 80s-style pop on that record, which I didn’t like. Clannad, to me, was a thing of art that didn’t follow fashion. A lot of the synth sounds were quite 80s prog, mind!”

The 1990s saw the departure of Pol from the band, intent on pursuing an offer Peter Gabriel had extended to him. “I’d come to a point where I wanted to experiment,” he recalls. “I’d been asked by Peter when we were in Real World Studios to do some production, so I wound up working out of there for four or five years. It was almost like going back – while I write from a place of construction, it was deconstruction there. It came from instinct.”

That led to something of a departure in his next musical project: Trisan, an experimental three-piece with Japanese percussionist Joji Hirota and Chinese flautist Guo Yue. “Real World was a masterclass, then Trisan were really stripping it right back. The last time I’d been on stage, there were 12 or 13 people there.”

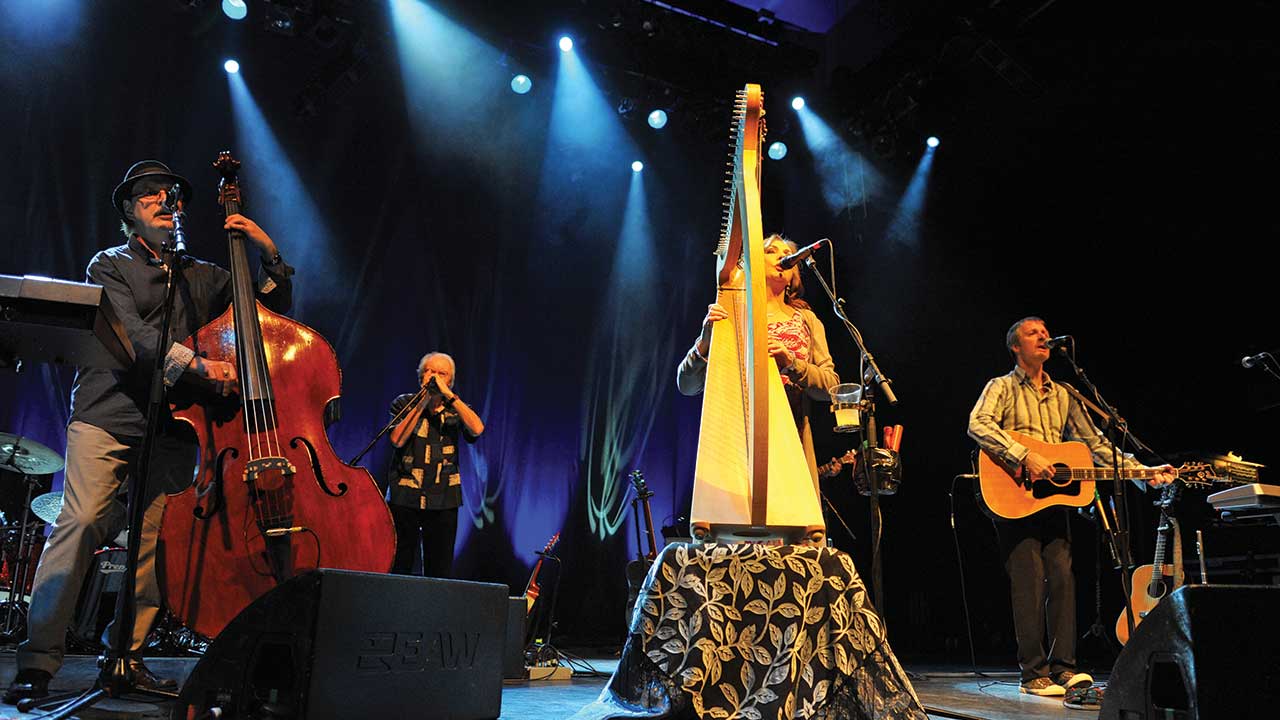

Meanwhile, Clannad – now led by Ciaran – entered their third phase, in which they secured a trademark approach which remains more or less in place today. That included a stack of collaborations with some prog names: Mel Collins (King Crimson), Anton Drennan (Genesis, Mike & The Mechanics) and Vinnie Colaiuta (Frank Zappa).

Ciaran recalls: “Being with a major label gave us the chance to experiment with people who drifted into the studio. Anton Drennan was always influencing us. Mel fitted like a glove, being in bands like Crimson – the deal was we let them do their own thing and Mel loved the band for that. We gave him one playback and told him, ‘Here are the chords – have fun!’ I was delighted to play with Vinnie, who was on drums for Lore.’”

Donockley cites Lore (1996) as being among Clannad’s very best outings, calling it “their most prog album for me, just in its ‘this is us’ approach. It’s a massive-sounding album, and to me was a killer return to form.”

He went on to work with Moya Brennan on her solo album Two Horizons, and recalls “late nights round the kitchen table with Pol, initiating him into the cosmic wonders of Thomas Tallis.” He adds: “They’re a delight to be with. Moya is the real thing and Pol is deeply splendid, and definitely progressive in his total willingness to experiment.”

The Brennan brothers – Pol returned to the fold for 2013 album Nadur – are comfortable with Clannad being described as a prog band, and themselves as prog musicians. “It started for me when I discovered my father had a double bass from his showband days, which I jumped on without lessons,” Ciaran says. “The influences just came out as soon as we rehearsed in my father’s tavern. I would be in charge of a lot of the arrangement and whatever I was listening to at the time went in.”

Pol believes the attitude of blending influences which haven’t previously been put together remains a strong element of his band’s music – and of the entire prog world. Namechecking fledgling Irish outfit Shattered Skies, he says: “Prog is just huge, isn’t it? When I go to write, the first part is a riff for me, and the prog bands I listen to are all riffs and counter-riffs with amazing syncopation.

“The thing with me is, I’ve always rocked the thing out. In my head I’ve always looked for the riff, looked for a bit more cut into anything. When we’re doing a nice ethereal thing, I’m like, ‘It’s really nice, but we need to get a cut through it.’ Unconsciously it was always a part of the sound, and it was as important as the ethereal stuff.”

Rocked out or not, there’s certainly a lot more to this mystic crew than anyone would expect.

This article first appeared in issue 43 of Prog Magazine.