For Kirk Hammett it was late afternoon in the US. For me it was early morning in England. But for both of us time was moving backwards as we recalled the fallen soldier who put the metal into Metallica: their former bassist Cliff Burton.

“Cliff had a lot of integrity,” Kirk said, quietly. “And his way of expressing that integrity was in one stock sentence which I still use to this day, and it was: ‘I don’t give a fuck.’ He really just cared about the music and the integrity behind the music. He was just very, very real.”

He certainly was. You only had to look at him to see that. The long, straight hair, parted down the middle; the moth-eaten cardigan and bell-bottom jeans; the weird little bum-fluff ’tache; the tee with some obscure band on it. At a time when poodlehair, Spandex and make-up were the norm in rock, these were all signifiers of what made Cliff Burton different, signposts to a soul born old that didn’t know how to compromise. That truly didn’t give a fuck.

Kirk sighed. “I don’t know if he knew somehow that his time was limited, but he really lived it like it was his last day, because he just wouldn’t settle for anything other than what he believed in. And that taught me a lot. To this day there are situations that I’m going through, and I can just picture Cliff saying: ‘What’s real to you? What really matters?’ And he would go through a bunch of points that didn’t really matter. He would name them off, and at the end of each one he’d say: ‘I don’t give a fuck!’ He was a very, very strong guy. Stubborn at times, and because of that he and I would clash sometimes. But we really were just bros, and he was a big influence on all of us.”

He remains so to this day. The legend of Cliff Burton has been the biggest unifying influence on all subsequent generations of heavy metal bands, whatever their stripe. Being true to yourself may have been the founding tenet of the original rock and metal giants, but by the time Metallica came along to redraw the musical map in the 80s, metal had become codified. The rules had straightjacketed the music’s essential, freewheeling spirit. Cliff Burton made it his mission to break those codes. Every musician since who has tried to do the same owes him big-time. Cliff was the fearless one, the guy who stood his ground, holding up his middle finger saying: “What’s real to you? I don’t give a fuck.”

Clifford Lee Burton was born February 10, 1962. His father Ray, from Tennessee, worked in San Francisco’s Bay Area as an Assistant Highway Engineer. Ray’s wife Jan was a special needs teacher. Cliff was the youngest brother to Scott David and Connie. When Scott died of a brain aneurysm when Cliff was 13, it had a profound effect on him, reinforcing the idea that life was not to be squandered on trying too hard to make other people happy.

Cliff had played the piano since he was six. Now he told others: “I’m gonna be the best bassist for my brother.” Jan was “totally amazed cos none of the kids in our family had any musical talent.” His early influence was a teacher named Steve Doherty. “He was the one who made Cliff take Beethoven and Bach, made him learn to read music etcetera.”

Speaking in 1987 with Cliff’s old friend Harald Oimeon, Jan described Cliff as “very quiet” and “normal”, except for his insistence from a very early age on being “his own person”. There was also a stubborn, Aquarian side to Cliff. Playing with kids outside was “boring”. Cliff preferred his own company, reading books and playing music. “He was very bright. In the third grade they tested him and he got eleventh-grade comprehension.”

Playing Little League baseball for the Castro Valley Auto House team, he was known as a big hitter. As a teenager, he took a Saturday job at an equipment rental yard called Castro Valley Rentals, where the older workers nicknamed him Cowboy, after the cheap straw hat he always wore to work. It was either that or get his hair cut – and Cliff wasn’t doing that.

Cliff was 14 when he began playing in his first band, EZ Street, named after a strip joint in San Mateo, He later played down the experience, dismissing EZ Street’s music as “pretty silly, actually… a lot of covers, just wimpy shit”. EZ Street afforded him his first chance to play real gigs, performing regularly at the International Cafe in Berkeley.

EZ Street also included guitarist Jim Martin, a likeminded soul who went on to join Faith No More. As Martin once observed: “Most of what you see on stage at a rock show, whether it’s a thrash gig or some heavy hip-hop club, it’s all about fantasy. The thing about Cliff was he was real. He wasn’t acting out the part to be in a band, he really was that guy. He never saw himself as a star. He was just another one of the guys.”

By the time Cliff graduated from high school in 1980, the Burton character was fully formed: an HP Lovecraft-reading, piano-playing homebody who loved beer, Mexican food, pot and acid. A free-thinker who drove a beat-up 1972 VW station wagon nicknamed The Grass-hopper, in which he mixed his Lynyrd Skynyrd tapes with Bach concertos. His favourite pastime was hanging out with his friends Jim Martin and Dave DiDonato, going fishing and hunting, or just sitting around into the small hours playing Dungeons & Dragons.

Enrolling at Chabot College in nearby Hayward, Cliff studied classical music and theory. He hooked up again with Jim Martin, and formed an instrumental trio, Agents Of Misfortune, a short-lived outfit in which Cliff first tried incorporating harmonics into his bass playing and improvising with distortion, a trick learned from Lemmy.

In 1982, Cliff joined Trauma, well-known to Bay Area scene-makers as a theatrical Iron Maiden-style band. He practised four to six hours a day, every day. There’s a wonderful video clip of them on YouTube. Amid billowing dry ice can be seen the incongruous figure of 19-year-old Cliff Burton, unself-consciously headbanging, his playing full of impressively odd jazz timings and psychedelic overtones.

When he decided to quit college to pursue music full-time, his parents were concerned. Jan: “We said: “We’ll give you four years. We’ll pay for your rent and your food. But after that four years is over, if we don’t see some slow progress or moderate progress, if you’re just not going anyplace and it’s obvious you’re not going to make a living out of it, then you’re going to have to get a job and do something else.’ He said: ‘Fine.’”

It was Brian Slagel who recommended Cliff Burton to Lars Ulrich. Slagel’s label, Metal Blade, had issued the first ever Metallica recording, Hit The Lights, on the 1982 compilation Metal Massacre. Trauma was one of the bands he was considering including on Metal Massacre II.

“The band was pretty good,” he recalls, “but the bass player was phenomenal.”

Knowing Metallica were looking for someone to replace bassist Ron McGovney, when Trauma played LA’s Troubadour club a couple of weeks later Slagel took Lars and James Hetfield there. Afterwards, "Lars came up to me and said: 'That is going to be our bass player!’" Nevertheless, it took months for Lars and James to persuade Cliff to even jam with them. Cliff lived in San Francisco, a cultural quantum leap away from the neon ooze of LA where Metallica lived.

Cliff told them: “I like it up here. So they said: ‘Yeah, well, we were thinking about [moving to San Francisco] anyway.’ So they came up, and we got together in this room, set up the gear and blasted it out for a couple of days. It was obvious straight away that it was a good thing to do, so we did it.”

What they hadn’t realised was that in Cliff, Metallica hadn’t just brought in a supremely gifted bass player, they had also acquired a teacher. As James later told me, as well as turning him and Lars on to artists like ZZ Top and Yes, Kate Bush and Peter Gabriel, Cliff was also “the most schooled of any of us; he had gone to junior college to learn some things about music, and taught us quite a few things. He had such a character to himself, and it was a very strong personality, he did creep into all of us eventually.”

Lars added: “Cliff was very, very different from James and [me]. He was an interesting mix of the kind of hippie, trippy, non-conformist vibe that was so well-known about San Francisco, kind of in his own head-space, and then also a whole side that was the redneck element – a beer-drinking, hell-raising, listening to ZZ Top and Lynyrd Skynyrd type of thing. So he was a very interesting mix of many different types of personalities. I was infatuated with his uniqueness. I was infatuated with his lack of conformity, and his insistence on doing his own thing, even to the point of ridicule.”

Cliff Burton was simply “not your basic human being,” as James, laughing, later put it. “He was really intellectual but very to-the-point. He meant business, and you couldn’t fuck around with him. I wanted to get that respect that he had. We gave him shit about his bell-bottoms every day. He didn’t care. ‘This is what I wear. Fuck you.’”

While Lars and James were clearly besotted with Cliff from the word go, the member of Metallica who grew closest to him was the next to join: Kirk Hammett. In common with Cliff, Kirk had studied classical music. Like Cliff, he still practised every day, based on lessons given to him by Joe Satriani. On tour in their earliest days, when they were stayed in a small motel, James and Lars would share one room, Cliff and Kirk the other.

“We were, in the first few years of the band, living in each other’s back pockets,” Kirk told me. “We were very close.”

At night, after a show, Kirk and Cliff would get their acoustic guitars out. “He didn’t play bass that much away from stage, so he was always playing guitar. And we would just jam. We had similar interests. He was into horror movies and HP Lovecraft, as I was. He enjoyed doing hallucinogenics, and so did I. He would tell me: ‘Hey, man, I just took some acid. Whatever you do don’t tell the other guys.’ I would say: ‘Sure, man.’ I didn’t take acid in any working environment, but it never bothered him.”

LSD, magic mushrooms, weed and pot… in Cliff’s hands these were creative tools, not just tickets to ride. Or as Cliff put it: “You don’t burn out from going too fast. You burn out from going too slow and getting bored.”

Kirk continues: “You also have to understand though, on an emotional level, we all tended to look up to him cos he was the guy with the most life experience. He was always the one who exuded the most confidence – the guy who had the best sense of ethics and morals. Whereas we were like slash and burn, seek and destroy, he would take a step back first and think about things and then slash and burn, seek and destroy. This was the guy who would sit around and listen to the Eagles and the Velvet Underground. He turned us on to R.E.M., he turned us on to Creedence [Clearwater Revival]. And he also loved Lynyrd Skynyrd too. Cliff was so far ahead of his time.”

A born leader, when the band’s first manager, Jonny Z, told them that distributors had demanded they change the proposed title of their debut album, Metal Up Your Ass, Cliff “got real mad” and yelled at Jonny: “Kill ’em all! Kill ’em all!” Jonny laughs as he recounts the incident. “The next thing you know, the album was called Kill ’Em All.”

With Cliff in charge of the on-the-road music, the others got lessons in the history of rock. It was also Cliff who instigated the band’s habit of always doing meet-and-greets after each show, no matter how small. According to their friend Bill Hale, “Cliff was the first one who went out and shook hands with the fans, cos Cliff was a fan. He wasn’t a goody two-shoes, though. Cliff knew how to party. “

We would [all] drink day in and day out and hardly come up for air,” Kirk recalled. Once Metallica began to achieve a level of fame, there were also groupies. “Lars would charm them, talk his way into their pants,” James recalled. “Kirk had a baby face that was appealing to girls. Cliff, he had a big dick. Word got around about that, I guess.”

It wasn’t until the band’s second album, Ride The Lightning, in 1984 that Cliff’s influence on Metallica really began to assert itself on record. According to producer Flemming Rasmussen, while it was “Lars and James that were more or less in charge” in terms of pure musical vision, “from an artistic point of view it’d probably be Cliff”. This showed not just in the shape of the HP Lovecraft-inspired monster album closer, The Call Of Ktulu, but also in the encouragement they needed to try the acoustic ballad Fade To Black. Cliff, saw it as a step forward.

Even the bands who opened for Metallica on tour took notice of their bassist. Joey Vera, bassist with Armored Saint, was especially drawn to Cliff. “We had a kinship, Cliff and I, because we also listened to some jazz fusion. He also had this really strong punk aesthetic… I always perceived Cliff as someone who was very strongly opinionated and very much not willing to do anything which would go against what he believed in. It was pretty evident back then that it mattered to the rest of the guys too.”

When Metallica made their first Castle Donington festival appearance, in 1985, just like every band low on the bill they were greeted by a hail of beer cans and plastic bottles of piss. Cliff, though, was unfazed.

“Donington was a day of targets and projectiles,” he told Harald. “I think they liked us, though.” At the Day On The Green festival in San Francisco two weeks later, James ran amok in a Jägermeister fit and trashed the dressing room. Cliff cooled him out with one look. “Cliff was the most mature out of all of us,” said Kirk. “When I’d do something stupid, or Lars or James would do something stupid, he was the guy who would say: ‘What the hell were you thinking?’ He was always the guy to reprimand us.”

When Bobby Schneider became their tour manager in 1985, he says it was clear that “Cliff was the backbone. Cliff was the guy who everybody looked to. If there was something Cliff wasn’t gonna like, it wasn’t gonna happen. No one fucked with Cliff.”

But no one, not even Cliff Burton, can cheat death. Cliff knew that. What he couldn’t have known was how cruelly death would play the game, snatching him away just as it seemed things were reaching their zenith in his life, both musically and personally.

The third Metallica album, Master Of Puppets, released in March 1986 just six months before Cliff died, wasn’t just a new peak for the band, it was a game changer in the history of rock and metal. It was the springboard for the astonishing success Metallica would later enjoy, and it seemed like it would be the start of the most remarkable lineage of albums since Led Zeppelin in their heyday. Instead it became the full stop that nearly finished off the band – the beginning and end of an era all in one.

Although Cliff received co-writing credits on only three of its eight tracks, Kirk feels that “people don’t talk enough about Cliff’s contribution to that album. I remember him playing the intro to Damage, Inc on the Ride The Lightning tour. It has all those bass swells and harmonies on it. I remember him saying, ‘Yeah, it’s based on a Bach piece.’ I asked him which one and I’m pretty sure he said it was Come Sweetly Death or something like that.”

The piece Kirk’s referring to is Come, Sweet Death, from the 69 Sacred Songs And Arias that Johann Sebastian Bach contributed to Georg Christian Schemelli’s Musical Songbook, nearly a thousand song-texts written as musical notation indicating intervals, chords and non-chord tones in relation to a bass note, providing harmonic structure. A very Cliff-like musical preoccupation.

Outside the studio, when Cliff and Kirk weren’t getting wasted in their hotel room, “we’d go out and play poker for eight hours straight after being up for twenty-four hours. We’d find a seafood restaurant that was open, eat raw oysters and drink beer, scream at the natives while we were drunk.” They were, he said, “some of my best memories” from that time.

It seemed nothing could stop Metallica. By summer 1986, Master Of Puppets had sold more than 500,000 copies, giving the band their first gold record and taking them into the US Top 30 for the first time.

Over three decades later, it has now sold almost seven million copies in America alone, and almost as many more around the world. Kirk recalled a meeting on the back of the tour bus when they were told they now had enough money to put down payments on their own houses: “The first thing that Cliff said was:, ‘I wanna house where I can shoot my gun that shoots knives!’ That was like a typical Cliff Burton thing to say.”

For Cliff, success was not an end in itself. This was just the beginning. Backstage at Birmingham Odeon, a young music journalist named Garry Sharpe-Young asked Cliff what the band would do if one of them died.

“What we were actually discussing was the hypothesis of Lars meeting his maker,” SharpeYoung recalled. “Cliff said they would have a big drunken party in his honour, and then get in a new drummer – fast.”

After a final climactic show in London, the band set off for dates in Europe. At the third show, at the Solnahallen in Stockholm, James – who until then had been unable to play guitar since a skateboarding accident three months before (roadie John Marshall had played guitar during James’s convalescence) – played superbly, the band back to their classic four-man shape.

Flying high again, Metallica outdid themselves, Cliff hitting new heights as he added a bizarre yet affecting version of The Star Spangled Banner to his usual bass solo, headbanging around the stage, his right arm windmilling. Lately he’d complained again of back pain. Not that night, though.

Afterwards, they climbed aboard the tour bus for the drive to the next day’s show in Copenhagen. It would be a long journey and the bus was cramped. Kirk and Cliff cut cards to see who got a more comfortable window-side bunk, Cliff winning when he drew the ace of spades. He and James stayed awake a little longer, James drinking vodka, Cliff smoking a spliff. Their bunks were at the back, next to each other. They both nodded off. The whole bus was silent when it began to leave the road...

As we now know, Cliff died in the crash, his body thrown through the bunk-side window and crushed by the weight of the bus falling on him. Back at the hotel that first night without Cliff, they got drunk. No matter how much they drank, none could find sleep. James fell to pieces, grief-stricken one moment, full of rage the next.

At four in the morning, the others could hear James drunk in the street outside, screaming: “Cliff! Where are you?!” Kirk couldn’t bear it and burst into tears.

The news travelled fast. Gary Holt of Exodus was “moving a twenty-five-gallon fish tank” out of his parents’ house when he heard. “Usually when you hear about a musician dying, it’s at his own hand – you know, drug overdose, chokes on his vomit, shit that would have been old hat. But dying in a bus crash? That was the first I’d heard of that.”

Jim Martin heard from Cliff’s mother, Jan. “My heart sank.” Cliff, he said, “was part of the think tank.” Jim was due back on the road the next day, and travelled home in between tour dates to attend his funeral.

Dave Mustaine turned to drugs: “I went straight to the dope, man, got some shit and started singing and crying and writing this song…” The song was In My Darkest Hour, the centrepiece of the next Megadeth album, So Far, So Good… So What!.

There was a memorial service back in San Francisco during the first week of October. Cliff’s funeral was held on Tuesday, October 7, at Chapel Of The Valley in Castro Valley, where he had lived with his folks most of his life. As well as Cliff’s immediate family, his girlfriend Corinne and best pals Jim Martin and David DiDonato were there, along with the rest of Metallica, plus Bobby Schneider and their co-manager Peter Mensch.

Other mourners included all of Exodus, Trauma, and Faith No More drummer Mike Bordin. Cliff’s ashes were taken and spread at the Maxwell Ranch. As DiDonato later recalled: “We stood in a large circle, with Cliff’s ashes in the centre. Each of us walked into the centre and took a handful of him and said what we had to say… Then he was cast on to the earth, in a place he loved very much.”

Gary Holt recalls: “It was a sombre affair, to say the least. But then you gather up at someone’s house after and you get drunk and share a laugh, you know?”

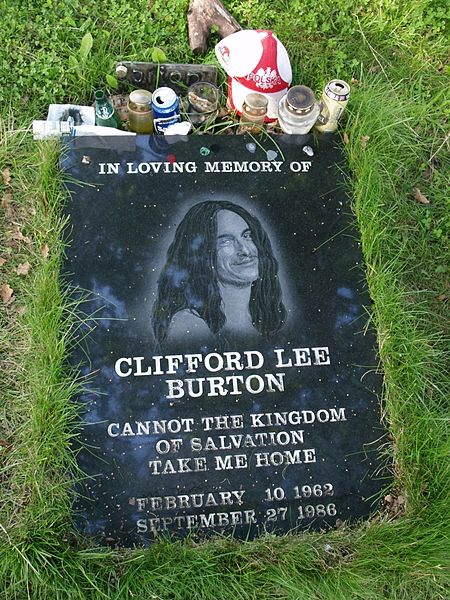

A commemorative headstone was laid, engraved: IN LOVING MEMORY OF and below that a picture of Cliff taken not long before he died. Underneath: CLIFFORD LEE BURTON CANNOT THE KINGDOM OF SALVATION TAKE ME HOME, then finally: FEBRUARY 10 1962 SEPTEMBER 27 1986.

The aftershocks of Cliff Burton’s death would continue to reverberate around Lars Ulrich, James Hetfield and Kirk Hammett for the rest of their lives. Kirk: “When I first joined the band there was a huge infusion of new energy, and up until Cliff died we were just so psyched about everything and life in general. But that kind of ended when Cliff left.” He paused then added: “I still think about him every day… Something he said, something he did, just… something.”

A few months before he died, Cliff was asked what advice he had for aspiring young musicians. He replied: “When I first started, I decided that I would devote my life to it.” Devotion, he said, was the key. “To absolutely devote yourself to that, to virtually marry yourself to what you’re going to do and not get sidetracked by all the other bullshit that life has to offer.”

Metallica’s search for a new bassist began almost immediately – Jason Newsted was appointed within weeks of Cliff’s funeral. No real replacement for Cliff Burton has ever been found, though. Instead his spirit lives on in Metallica. Speaking now, James Hetfield says that whenever Metallica are involved in new, exciting projects, “there’s always thoughts, when we’re doing things, in the back of our minds: ‘Wow! Cliff would just love this’, you know?”

Certainly there’s little doubt that Cliff – the guy who turned the others on to Lou Reed’s 60s band the Velvet Underground – would have been stoked by the Lulu album, released in 2011.

“I’m still close with Jim Martin, who was an extremely great friend of Cliff’s,” James said at the time of that record, “and he is unbelievably excited about this Lou Reed/Metallica collaboration. We talked a bit about Cliff, and about him being alive in our spirit around the whole thing, in the studio when we were doing it. It’s raw, it’s loose, and there’s a lot of floor takes. It’s kinda extreme jamming.” Something Cliff always encouraged.

“Absolutely,” agrees James. “Oh, he loved to jam and just go crazy with sounds. He loved soundscapes, but in a heavy way. He was a big fan of that and a big fan of Pink Floyd and some of the really deep but heavy stuff. Lou’s lyrics were very intense and dark, and that was something that Cliff turned us on to as well. He was a unique kind of guy, and Lou is too.”

Cliff Burton – the uncompromising soul and conscience of Metallica, in life and, still, in death. We salute you. There was never a metalhead like you before, there will never be a metalhead like you again.

Published in Metal Hammer #224

Headstone photo by Thrudgelmir on Wikipedia. Licensed via Creative Commons.