Cock Sparrer, an East End London street-punk institution, with a core quartet of members who’ve been together since 1972, have never been more in demand than they are right now. According to their imposing, stentorian lead vocalist Colin McFaull, they have enjoyed a career in reverse. “Maybe bands in future will follow our model,” he says, “shun big record deals to follow their own path; leave big gaps every few years… Not make any money out of it.”

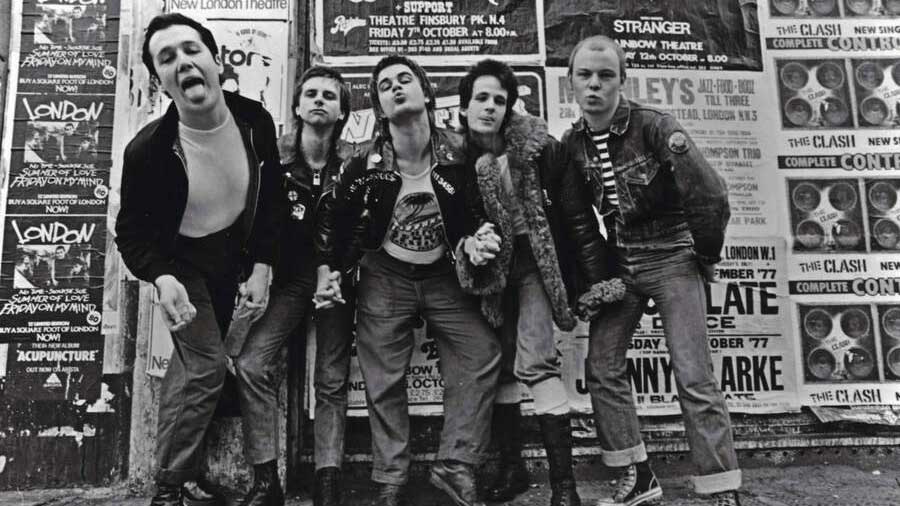

In 1977, Cock Sparrer’s faces (in the eyes of a music industry and press already blind-sided by a spike-topped, McLaren-marketed, hippie-averse new order) simply didn’t fit. They looked like they’d just walked off the terraces. They were actually working class. Their music a shade too brutal, their hair a couple of grades too cropped, Cock Sparrer were just too punk.

Maybe, because they’d already been hard at it for five years and had honed their brand of sonic aggravation closer to the bone than anyone else (until Sparrer-indebted Oi! arrived on the fringes of the mainstream in ’81), they were simply too far ahead of the game.

So while they couldn’t get arrested (actually, poor analogy, they very much could get arrested) in 1977, by 1982 they’d been embraced as underground elder statesmen by a never-more-receptive domestic punk scene. By the early 90s they were being held up as living-legend role models by such leading lights of the US crossover hardcore scene as The Dropkick Murphys and Rancid.

When Cock Sparrer (né Sparrow) started out – with a core line-up (then as now) of singer McFaull, guitarist Mickey Beaufoy, bassist and songwriter Steve Burgess and drummer Steve Bruce – their musical role models were local heroes and mod godheads the Small Faces, along with the glam stars of the day: Slade, T.Rex, Roxy Music, Bowie, Mott, Alice Cooper. Their ambitions were modest: “We’d copy songs that were in the charts to try and pull a few birds down the youth club, but it didn’t always work out, obviously.”

Four years on, it became apparent from reading music press reports that they were not alone in touting crop-haired, glam/ mod-based, short, sharp and aggressive shocks. Something similar was rumbling up west. And in the summer of ’76 a visit was made to Chelsea’s King’s Road to deliver a demo cassette to Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren.

“We said: ‘Have a listen to this, this is the real stuff’, and arranged for him and one of his guys to come and see us rehearsing over a pub in the East End,” recalls McFaull. “When they turned up they had on bondage trousers, cowboy hats, spurs on their boots, and we were in jungle greens and Dr Martens. It was like the King’s Road meets the Army & Navy store. We played a couple of our terrible compositions, and though nothing was said, you could tell it was ‘not really for us’.”

Although invited to stay for a beer, McLaren – unforgivably – left without offering to stand his round.

Undeterred, Sparrer simply soldiered on: “We just circled the wagons and cracked on, still in the belief that something might come of it.”

And as punk exploded rapidly, something did come of it. Sparrer signed to Decca Records (“One of our managers also looked after John Miles, who’d just had a big hit on Decca with Music, so us signing with them seemed like a shoo-in”) and went on to release their debut single Running Riot in May ’77

Unfortunately, Decca were not the ideal punk label – they were more used to dealing with classical artists (other punk-era signings they spectacularly failed to launch included Slaughter & The Dogs and even Adam And The Ants, who ultimately hit mainstream pay dirt with CBS).

While Decca had little clue what to do with their lively charges (their second single, a cover of the Rolling Stones’ We Love You – in a picture-free white sleeve – didn’t arrive until November, and a six-month gap between releases in ’77 was roughly equivalent to six years now), the band didn’t exactly help matters.

“We were antagonistic and unhelpful,” McFaull admits. “That’s why We Love You came out in a white cover. Every design they threw at us, we said: crap, we’re not having it. “Decca weren’t a good match for us. They weren’t stupid, they just weren’t in tune with what was going on. Badges were very important in those days. The cool ones, for the Pistols and the Clash, were tiny. Ours were massive, like the ones that come with birthday cards.”

Their self-titled debut album was finally released in 1978. But only in Spain. Meanwhile, they’d picked up a reputation for trouble. “There was some violence at the gigs,” says McFaull, “but it wasn’t anything we generated. We had a regular following of about a dozen lads, known as The Poplar Boys, but they were more responsible for stopping fights than starting them. We stopped playing for a while because we weren’t interested in anything where someone might get hurt. Every gig, the van’s windscreen got smashed or the tyres were slashed. We just thought we don’t need this.”

Cock Sparrer split, for the first time, in ’78 and simply got on with their lives. They got married, got jobs, but remained close, “a band of brothers”. Meanwhile, Oi! (an unvarnished brand of hard-core street punk championed by Garry Bushell in weekly music paper Sounds, and defined by a series of compilation albums – featuring tracks by, the now tantalisingly absent, Cock Sparrer) appeared on the scene in 1981, sparking the interest of a whole new generation of fans and spurring Cock Sparrer back into action.

In ’82 they recorded their second, most enduring album, Shock Troops, and remained in harness for Running Riot In ’84, before ultimately calling a halt to proceedings once more.

During their next eight years of near stasis, Steve Bruce opened a couple of pubs, ending up at The Stick Of Rock on Bethnal Green Road, playing host to a number of gigs in the early 90s. Guitarist Daryl Smith “was a fan who used to play with his band The Elite at Steve’s pub,” recalls McFaull. “Steve was working behind the bar, and when people found out who he was there was almost a reverence.”

“I used to drag him up on stage,” says Smith (now Sparrer’s rhythm guitarist of 32 years standing). “People couldn’t believe it. We were like: ‘A real live human member of Cock Sparrer?’ There were never any photos of them from back in the day, they were like mythical creatures.”

Inevitably, the nagging for the band to re-form resumed, but Sparrer – completely oblivious to just how much their legend had grown in their absence – were sceptical.

“We were approached by this guy who wanted to put us on at the Astoria,” says McFaull, “and we were like: ‘What’s the point? No one will come.’ We didn’t want him to lose money, he was a nice bloke, so we agreed to do it for a couple of hundred quid. We were expecting tumbleweed, two men and a dog, but it was a brilliant night, sold out. Because what we didn’t know was that for the last few years people like Rancid and Dropkick Murphys had been referencing us as an influence.”

Having re-formed, with Smith on board, Cock Sparrer (increasingly hailed as the template for much of modern street punk, with a largely untapped fan base in the US, South America, mainland Europe and Japan) set to work. Touring sporadically and whetting appetites at international punk festivals, they released Guilty As Charged in ’94 and Two Monkeys in ’97, gradually nurturing and growing their fan base. They couldn’t remain the underground punk scene’s best-kept secret forever.

Fiercely independent (they’ve not been beholden to any label since their Decca days), they finance and own their own recordings. With three unyielding, uncompromising, unmistakable albums since the turn of the century (Here We Stand, Forever, Hand On Heart), today’s Cock Sparrer are as strong, possibly even stronger than they’ve ever been. Their low-key, hit-free career-in-reverse may never have afforded them the trappings of fame and fortune, but they’re still alive, still in fine, feral form and, most importantly, still friends.

“It’s a lovely situation,” concludes McFaull. “We’re six mates – five in the band and a tour manager I’ve known since I was five years old - who get on a plane on Friday, have fun shouting at some nice people on Saturday and come home on Sunday. Who wouldn’t want that?”

The history of UK punk has been written and rewritten again and again, but rarely reassessed. There’s an enduring unchallenged orthodoxy that invariably puts the Sex Pistols/Clash axis at the centre of the story. It was, we’re repeatedly told, a metropolitan art-school movement owing much to US musical progenitors, The Situationist International and King’s Road exhibitionism. Whenever they make those fancy-schmancy BBC4 punk documentaries, Cock Sparrer are never there. Now that prevailing punk bears a closer resemblance to Shock Troops than to Never Mind The Bollocks, maybe it’s about time that they were.

Cock Sparrer's eighth album Hand On Heart album is out now.