Jerry Gaskill has a vivid memory of being chased down the street by Layne Staley of Alice In Chains. Gaskill’s band, the Texan trio King’s X, had rolled into Seattle on the tour to promote their debut album, 1988’s Out Of The Silent Planet. Many of the leading players in the city’s nascent grunge scene had turned out to see them, including members of Soundgarden and Mother Love Bone as well as Alice In Chains.

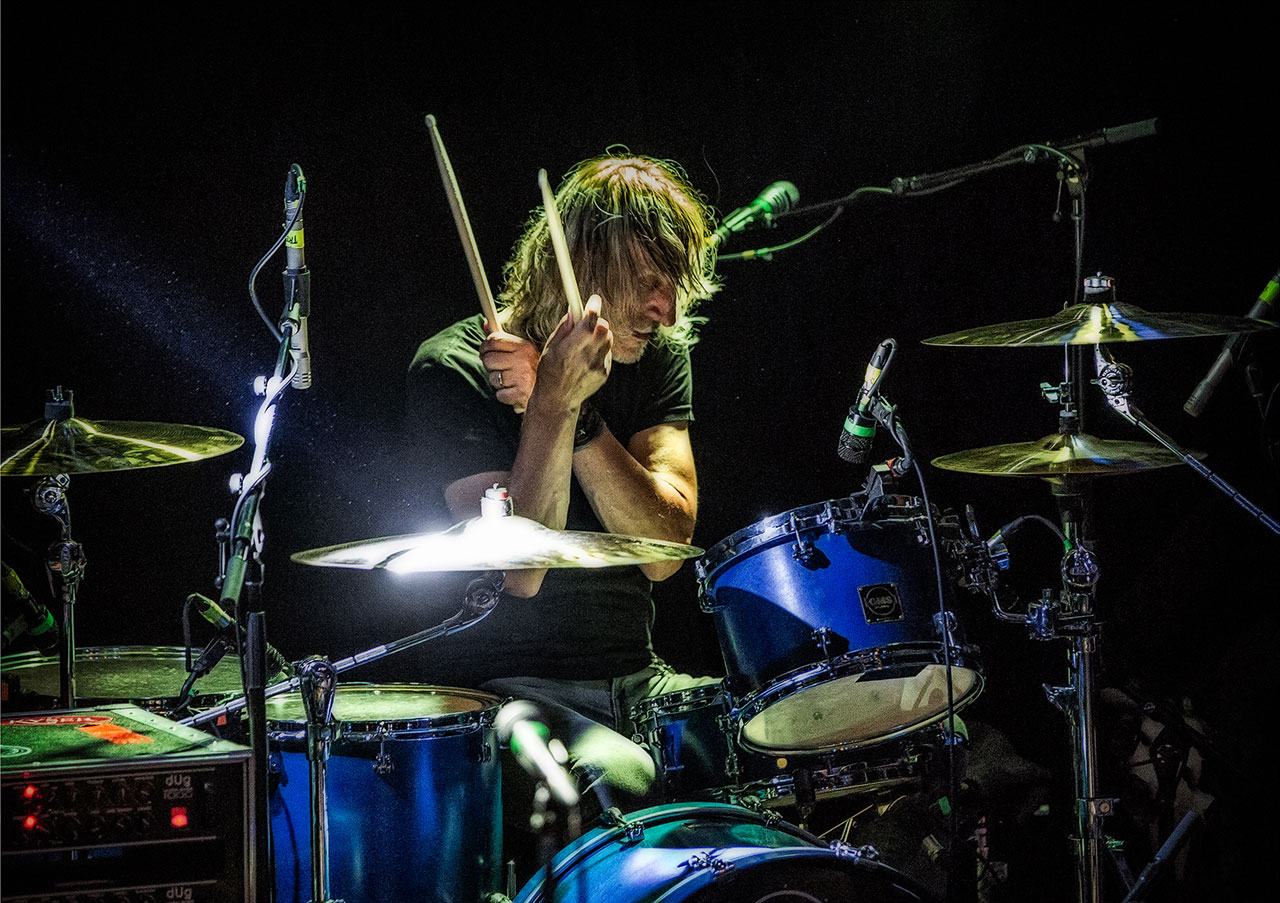

It was after the show that Gaskill found himself accosted by Staley. The Kings’s X drummer was on his way to get some food when he heard footsteps hammering behind him.

“I see this guy hurtling down the street towards me, going: ‘Jerry! Jerry! I love your band, man!’” remembers Gaskill, as softly spoken and modest a man as you could ever hope to meet. “It was Layne. For some reason they all were really supportive of us up there. We became friends with a lot of those guys.”

Staley wasn’t the only superstar besotted with King’s X. In the early 90s, at the height of his own band’s success, Pearl Jam bassist Jeff Ament declared on MTV that “King’s X invented grunge”.

Ament’s rationale was sound. In the era of Guns N’ Roses and Poison, King’s X, with their drop-D guitar tunings, sounded like nothing else around. But even if they had sparked off that movement – which is debatable anyway – that doesn’t tell the whole story. They also drew on a deep well of influences that ran from The Beatles (their effortless melodicism and immaculate harmonies) to Motörhead (the metallic ring of frontman Dug - formerly Doug – Pinnick’s bass sound was the heaviest thing this side of Lemmy) and even Joshua Tree-era U2 (their songs possessed an enigmatic, uplifting, spiritual edge).

The British music press went into meltdown. Out of nowhere, this trio of unlikely looking men in their greatcoats and military jackets became magazine cover stars. The band’s first three albums – Out Of The Silent Planet, 1989’s Gretchen Goes To Nebraska and 1991’s Faith, Hope, Love – were each individually hailed as the future of rock. But for all the talk and all the column inches, King’s X never broke through. They had the world at their feet, but the world had turned its back and wasn’t listening.

Today the band are still here. They have endured the machinations of the music industry, weathered personal turmoil and survived literally near-death experiences. The hype that initially surrounded them dissipated long ago, but the devotion among those who know them has not. But the question remains: why the hell weren’t King’s X the biggest band on the planet?

Almost 30 years on, the answer still isn’t clear. As Gaskill, Pinnick and guitarist Ty Tabor all freely admit, King’s X had everything going for them: a supportive label, the weight of the press behind them, and some of the greatest and most emotionally engaging music of the era.

Pinnick has one theory. He puts it down, at least in part, to racism. Tall, striking black men with mohawks weren’t exactly common in the rock scene of the late 80s; they still aren’t today.

“Black singers in a rock band don’t do that well, because white dudes want to hear a white guy singing about how they’re doing,” says Pinnick, whose ageless looks belie his 66 years. “I just don’t think they related to me. In America we still have that racial thing going on: ‘Oh, I like the band but the singer’s black.’”

Pinnick says this with little rancour, even though he is fully entitled to be angry about it. Like his bandmates, the singer and bassist is laid-back and effortlessly friendly, although his mellowness is undercut by what seems to be a deep-rooted insecurity about his own considerable talents. “Totally. I’m one of the most insecure people you’ve ever met,” he says. “I mean, I can barely look in the mirror at myself.”

In the 1989 King’s X song Over My Head – the closest thing the band ever had to a hit single – Pinnick paints a vivid, joyous picture of his Christian upbringing, growing up in his great-grandmother’s house. But the reality was very different.

“I had a rough time,” he says now. “She was very religious, like the song says, but she was very, very right-wing. I couldn’t go to parties or go dancing or listen to rock music or anything like that.”

Still, Pinnick describes himself as “pretty dogmatic when it came to religion back then”. And it was Christianity that brought King’s X together in Springfield, Missouri in the early 1980s. All three were fully paid-up members of the Christian rock scene, that self-contained if strangely disconnected world where music meets hard-core religion. It’s a place that outsiders don’t get to look into, and insiders rarely get to leave. But despite their strong individual faiths, the trio were aware of the limitations of the Christian scene and wanted no part of it.

“We were Christians in that we were trying to be the real deal, the kind of people that tries to help others out, that tries to be an example of goodness,” Ty Tabor says in a southern drawl as wide as the Mississippi River. “But as far as the whole Christian rock industry went, I was just disturbed by the whole thing. It was all about packaging and selling a gimmick. There was an immense amount of BS and propaganda involved that had nothing to do with religion or belief.”

“I’d told Jerry and Ty I wanted to put a band together with them, but I didn’t want it to be a Christian band,” says Pinnick. “I didn’t want to play Christian churches. I didn’t even want to be associated with it, because the ‘C’ word was the kiss of death in the 80s. Christian bands were just deemed a joke.”

The band’s career in secular rock’n’roll began inauspiciously. Initially calling themselves The Edge, they started out covering the chart hits of the day. By 1983 they’d changed their name to Sneak Preview (a moniker that makes all three wince audibly) and recorded an album of new wave-inspired songs that contained elements of the King’s X sound.

It wasn’t until they moved to Houston, Texas in 1987 that things began to properly coalesce. It was there that they met Sam Taylor, who would become their manager, mentor, producer and, in the band’s view, ultimately tormentor. It was Taylor who inspired the band to call themselves King’s X – the name of a group his brother had played in during the 60s.

“We just kind of adopted the name and kept it,” Pinnick says with a laugh. “We didn’t really like it – I still don’t. But it’s been that way for thirty years. I guess there’s no need to change it now.”

According to the three members of King’s X, Taylor was a hard taskmaster, always pushing the band to their limits. His meticulous, spare-the-rod approach meant they spent long and painful hours in the studio making their debut album, Out Of The Silent Planet (its title lifted from a novel by the devoutly religious author CS Lewis). Whether it’s down to bad memories or just residual insecurity, Pinnick admits that at the time he didn’t see how great an album King’s X had made.

“No, I thought it wasn’t that special. I thought people would ignore it, I really did. I couldn’t compare it to anything. All I knew was that it didn’t sound like the stuff that we had been listening to. I really, really thought that maybe nobody would like it.”

When it was released in March 1988, Out Of The Silent Planet was received rapturously, at least by the British press. King’s X were a bona fide sensation. Their debut UK gig, at the Marquee club in November 1988, was the hottest ticket of the year.

“The place was completely packed and people were so excited,” says Gaskill. “I’m thinking: ‘Wow, this is going to work. We’re going to be like The Beatles.’ But of course that didn’t quite happen.”

But outside of the more clued-in elements of the rock scene, no one knew quite what to make of King’s X. They were a three-piece comprised of two white guys and a black guy with a mohican. They sounded like The Beatles and Motörhead jamming to a gospel choir. They claimed they weren’t a Christian band, but such spiritually inclined songs as King and Power Of Love – not to mention their name, with its heavenly connotations and intimations of a cross in the shape of an ‘X’ – suggested otherwise.

“A lot of people wrote us off as a God band, even though we weren’t,” says Pinnick. “We just had that Christian stigma.”

Despite the acclaim that was heaped on Out Of The Silent Planet and its equally fêted follow-ups Gretchen Goes To Nebraska and Faith Hope Love, for King‘s X the needle stubbornly refused to budge above the level marked ‘cult band’. In the UK they could easily pull in a couple of thousand devoted fans a night, but that was as far as it went. The mainstream breakthrough never came. And in the US they barely registered at all outside a few select enclaves, such as Seattle.

“We were plenty happy to have the buzz, of course,” says Ty Tabor. “But buzz doesn’t amount to as much as people think.”

Still, Pinnick, Tabor and Gaskill could take solace in the fact that those who did know about them absolutely loved them. And it’s not difficult to understand why. All these years later, those first three albums still have a magic to them. Against the context of glam-metal and even grunge, they sound unique and otherworldly, simultaneously spiritual and earthy.

But even the most inter-dimensional of bands must face the harsh realities of the music industry. For King’s X the gulf between what people were saying about them and what was actually happening was only exacerbated by the gruelling workload that came with being a band that had released three albums in as many years.

Their self-titled fourth album, released in 1992 via Atlantic Records, was shot through with a darkness that its predecessors didn’t have. Within a few months of its release King’s X had parted ways acrimoniously with their manager Sam Taylor, the man who helped get them where they were – wherever the hell that was. “He just quit,” says Pinnick. “He had such control on us that when he left we had nothing. No contacts, no money, no way to even know what we were going to do. We were just like orphans on the street.”

The split from Taylor was difficult, but ultimately liberating. The first album they made without him, 1994’s grungy Dogman, is the sound of a band unfettered. Produced by Pearl Jam associate Brendan O’Brien, it’s the closest King’s X ever came to making a punk record.

“Brendan got the best out of us,” says Tabor. “Before, there was always a kind of dark energy in the studio, a pressure that we all just wanted to be out from under. With Dogman we felt freedom.”

Those upheavals may have changed the way the band worked, but it didn’t make a lot of difference to how the world viewed them. According to Tabor, Dogman was one of the band’s better-selling albums. But it still only peaked at No.88 in the US.

There comes a point in every band’s life when they throw up their hands and say:‘Fuck it.’ That’s the moment where they either quit, or step away from the rat race and start doing exactly what they want, and damn the consequences. For King’s X, that point came some time in the mid-90s, after they’d been dropped by Atlantic Records following their sixth album, 1996’s Ear Candy.

“Atlantic did everything they could, but it was just hard to market us,” says Jerry Gaskill. “But I think we’d definitely realised at that point that we were never going to be as big as U2. And it was nice to just make music on our own.”

Anyway, Pinnick had more on his mind. For years he had secretly struggled with his sexuality, unable to reconcile his Christian beliefs with the fact that he was gay.

“I knew there was something different about me,” Dug says now. “My cousin told me when I was ten that if he found out that I was gay he would beat the shit out of me, and that scared me. I was ten! I didn’t even know about sex. And going to church with my great-grandmother, it was all hellfire and brimstone. If you danced you were going to hell, if you drank or smoked you were going to hell, and if you were gay you were definitely going to hell.”

He kept his feelings suppressed. Unsurprisingly, it had an adverse effect on his life.

“I grew to hate myself. I hated who I was, I hated my sexual orientation, I hated there was nothing I could do about it. Because it’s a hard thing to be gay in the world, and it’s a hard thing to let anybody know it. I mean, people would beat you up, you’re put in the category of murderers and child molesters, you’d get thrown out of the church…”

By the late 90s he decided that he’d had enough of the pain and torture and depression that came with keeping such a huge part of his life secret. In 1998 he announced publicly that he was gay. “One day I just did it,” he says. “I didn’t think about it. I do a lot of things without thinking.”

The band still had a strong Christian following, and Pinnick’s announcement caused shockwaves in that community. King’s X albums were pulled from many Christian record stores. It could have been the final nail in the coffin of the band’s career. Instead, says Pinnick, it was a final act of liberation.

“We became the pariahs of the Christian community,” he says. “They hated me for it. I still get mail from people going: ‘Come back to Christ.’ I just look at them and go: ‘There’s no fucking way I’m coming back to that.’”

These days the three members of King’s X each have a very different relationship with religion from the one they had 30 years ago. “I don’t call myself a Christian by any means, and I can’t find myself in any box whatsoever,” says Gaskill.

Tabor has a different take on things: “My faith has been changing for some while, and I will say that I have no problems with God, or whoever is behind all of this creation, because I just find it harder to believe that anything comes from nothing without cause or something behind it. But then again none of us can understand infinity.”

Pinnick is unequivocal. He says he lost his faith sometime around 1994. “The Bible says that being gay is an abomination to God, so I just figured: ‘Well, dude, you’ve lost me in every direction.’” He admits that it took eight years to “un-brainwash” himself. “I can state right now that I am not a Christian, and I’m happier without it.”

Maybe it was a product of age and the abatement of youthful hunger, but the 2000s found King’s X settling into a role as rock’s great shoulda-been-huge band. The albums they made – Please Come Home… Mr Bulbous (2000), Manic Moonlight (2001), Black Like Sunday (2003), Ogre Tones (2005) and XV (2008) – were uniformly excellent. And if the world had stopped listening, well, what did it matter? It’s not like it was paying much attention to King’s X in the first place.

But fate had one last turn of the cards left to play. In February 2012, Jerry Gaskill suffered a heart attack and was rushed to hospital, where he underwent emergency surgery. It was touch and go whether he’d pull through.

“My doctors tell me that my body just somehow cannot break down cholesterol,” he says. “And I just got a complete blockage. I was running, I was feeling good, but I guess I’d been dying the whole time because my arteries were so blocked. One night I just went completely down. I just died, and I have no recollection of it. Thankfully my future wife was there at the time. Had I been alone at the time, there’s no possible way I would have recovered. I’d have just laid there and gone on to whatever happens to you when you die.”

Just over six months later, Gaskill’s home in New Jersey was completely destroyed by Hurricane Sandy. Then in 2014 he had a second heart attack, necessitating a double heart bypass operation. Such a string of calamities would have driven a lesser man back into the arms of the church, but Gaskill insists his lack of faith remains unshaken, even if it has meant the time since the last King’s X studio album is now nine years and counting.

“I don’t know why that is,” he says. “I don’t think that’s a conscious decision. It’s just that things have happened along the way. And, you know, I died. That kind of put a damper on things for a little while.”

King’s X may have been quiet in recent years, but they never really went away. And now the wheels are grinding again. They’re back on the road in 2017. There’s even talk of a new album – the three of them are planning to start writing, with a view to a 2018 release. They’ve been through enough trials to make lesser men weep, but the greatest cult band of them all aren’t ready to call it quits just yet.

“The greatest cult band?” says Pinnick. “I’d rather be called a cult band than not be calle

X Marks The Spot

The Kings’ top tracks.

Goldilox

The band’s debut single, and Dug Pinnick’s heartbreaking letter to an unrequited love. The emotional highlight of both 1988’s Out Of The Silent Planet album and their career as a whole.

Power Of Love

The down-tuned guitars gives credence to those ‘inventors of grunge’ claims. But this Out Of The Silent Planet track wears its uplifting U2 influences on its sleeve.

Over My Head

Gospel meets metal on this high point from the band’s second album, Gretchen Goes To Nebraska.

Pleiades

Ty Tabor identifies Pleiades as the starting point for the King’s X sound, even though they held it over until Gretchen. As sparkling and celestial as the stars it was named after.

I’ll Never Get Tired Of You

Third album Faith Hope Love is more earthbound than its predecessors, though King’s X still pirouette off into the skies when the mood takes them, as they do here.

Not Just For The Dead

This track’s soaring, sitar-assisted chorus is a rare ray of sunshine on the band’s dark fourth album, recorded as their relationship with their manager/producer went south.

Dogman

The title track of their fifth album strips away the enigmatic gauze of the past to display a more musical approach that plays the grunge crowd at their own game.

The Train

Ear Candy (’96) was Kings X’s last album for a major label. But the shifting, prog-tinged verses and sunburst chorus of The Train shows they’d lost none of their invention.

Cupid

The initial hype had long worn off by 1998’s Tapehead, but the bassy power-pop punch of Cupid suggests that freedom suited King’s X just fine.

Charlie Sheen

2000’s Please Come Home… Mr Bulbous added a dose of hazy weirdness to King’s X sound, as on this nugget of cryptic psychedelia that has nothing to do with the actor of the same name.