Meeting Jim Steinman, the creator of Bat Out Of Hell, was a memorable experience.

After enjoying years of vicarious thrills from his widescreen, Technicolor songs – songs that accompanied me and a million others through teenage fumblings and sweatily unpleasant hormonal surges – the real thing was no disappointment.

He shook hands with a soft, pudgy mitt that had never seen a day's work; long, tapered fingernails and girlishly manicured nails. He had a huge rush of totally grey hair, a slobby unexercised body, a rounded moon-face that had rarely seen the daylight and voice like that of the cartoon character, The Hooded Claw. He wore an expensive leather biker's jacket on which naked women had been wonkily painted.

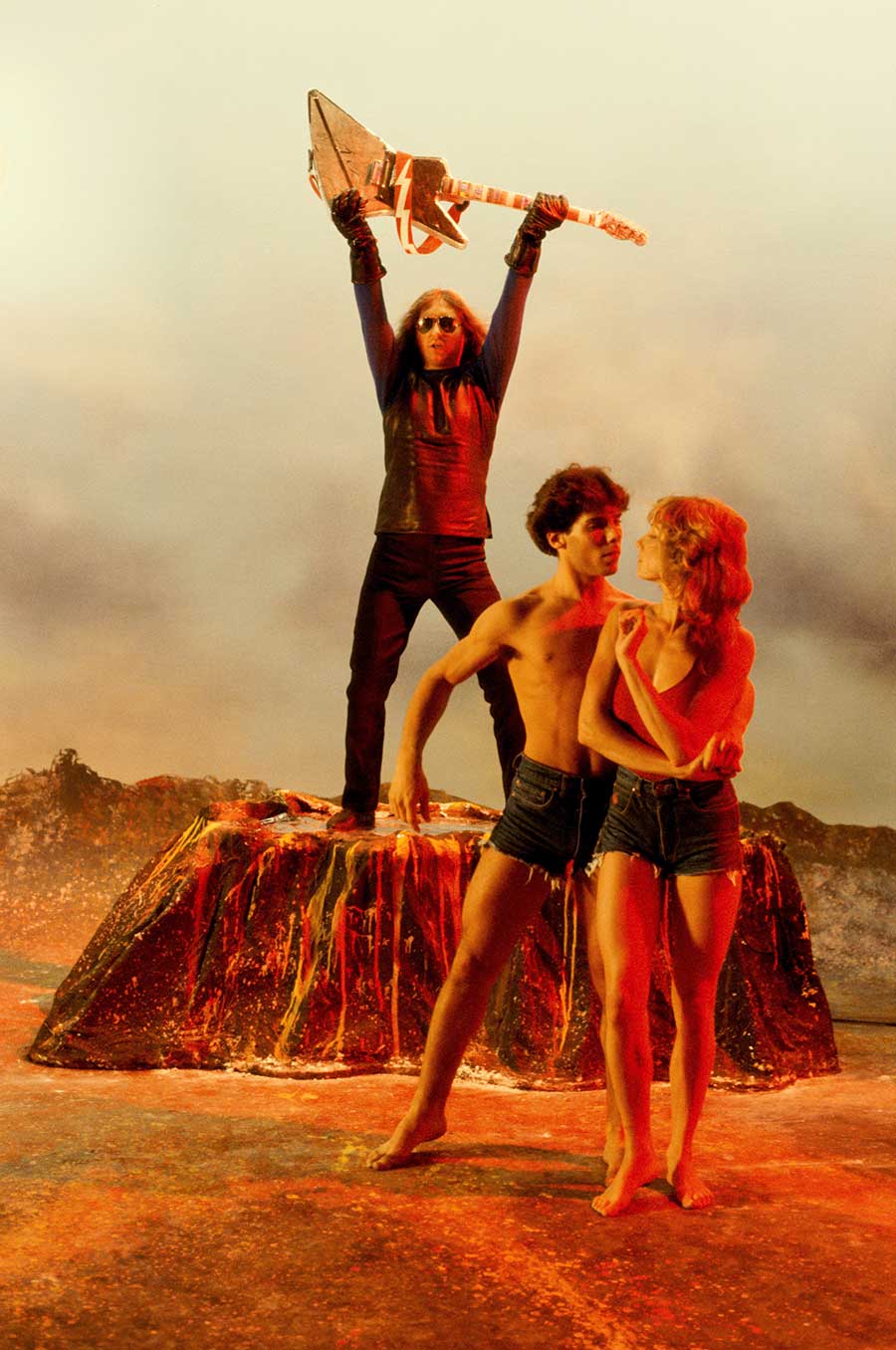

We were at Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire, where he was supervising a video for the track It's All Coming Back To Me Now, the first single from his Pandora's Box project. The director was perhaps the only man in the world who could match Steinman in the scope of his creative vision: Ken Russell. And even Russell, by now a ruddy-faced, well-lived sixty-something with Tommy, The Devils and Whore on his CV and years of working with Alan Bates and Ollie Reed under his expansive belt, seemed to be feeding off the kinetic blast of Steinman's particular madness.

The video script, such as it was, called for singer Elaine Caswell to be sexually aroused by a large python while writhing on a bed that lit up in time with the music, all the time surrounded by a group of bemused, semi-naked dancers on a day-trip from their regular gig in Cats. The two day shoot was over running badly, and the cost of continuing was £35,000 an hour.

Steinman casually offered to pay himself, and Russell nodded back and grinned. They were having a fun time, and over lunch they were plotting an unscripted climax to the video, one that would come as a shock to Virgin Records, who were nominally the clients. Steinman demanded – and Russell wholeheartedly agreed – that the only fitting end to the cut was for a man to ride a motorcycle up the steps of a local church-tower known to Russell, jump it out of the turrets at the top, and then explode.

To the surprise of only two men – Jim and Ken – the wardens of the 500-year-old church refused. But that was Jim captured perfectly in his moment: you start off by thinking big, and then you take it from there.

We met twice more over the next few days, and he proved a fascinating and complex man. He was obsessed with motorcycles, and yet he hadn't passed his driving test. The characters in his songs were heroic figures, beautiful, fragile and doomed, but he was a bachelor who lived a solitary life on a remote farm.

When we went to dinner, he ordered everything – literally everything – on the menu and then ate a bit of each. Aside from music, his great love was fine wine, and one of his managers told me that he wrote about every wine that he tasted in the same way he wrote his songs. "If it was published," he said, "it would be the greatest book on wine ever written..."

Above all, spending a little time with Jim Steinman proffered an insight into how someone could write a record as unique, as mad, as special, as crazy and as dumb and overblown as Bat Out Of Hell, still the biggest selling debut album ever released, and as of now, the third biggest-selling record of all-time.

As the saying goes, it's always the quiet ones that you've got to watch. A classmate of Jim Steinman's once said: "Jim knew what it meant to be cool and he knew that he wasn't."

Instead, the odd-looking kid who spent much of his time "imagining I had a bat perched on my shoulder" created in his head a place for the kind of man he knew he'd never be: a land for the heroic. Now he just had to convince the rest of the world.

Elsewhere in the country, under the endless skies of Texas, a class fat-kid, a big, big boy with a big personality felt a stirring too. In a scene straight from a Steinman song, he became so distraught at his mother's funeral that he grabbed her body and screamed at the undertakers, "You can't have her!" Shortly afterwards, his alcoholic father tried to kill him.

Of course, this left its mark on Marvin Lee Aday, who had, since Junior High, been known as Meat Loaf, and merely Meat to his friends. Meat Loaf was the kind of guy you notice, the kind of guy stuff happens to, and his path from Texas to New York was a colorful one. Aside from a walk-on part at the assassination of JFK and a job on a turkey farm, he was in and out of bands and drawn to the stage. His first success of note came when he nailed a role in the quintessential 60s wig-out nudie musical, Hair.

Jim Steinman, miniature bat-man, saw his future on the stage too. What made and continues to make him unique among rock music writers is that his writing was and is not influenced by blues or jazz, or even rock 'n' roll.

Instead, its roots are in classical composition based at the piano rather than the guitar. All Jim Steinman drew from rock music was its sense of wildness, of rebellion and its vast scale. He was quick to meld those values onto his regressive obsessions with teenage longings and lust, and his desire not to just write songs, but to create a parallel universe in which he could live.

"I never really saw classical music and rock 'n' roll as different. I still don't," he told me. "I grew up liking extremes in music - big gothic textures. I never have much regard for more subtle stuff. Dire Straits may be good, but it just doesn't do it for me. I was attracted to William Blake, Hieronymus Bosch, I couldn't see the point in writing songs about ordinary, real-life stuff."

He wrote several lengthy stage pieces: The Dream Engine, More Than You Deserve and Neverland. The first of these was completed while Steinman attended an exclusive New York State college, the private and secretive Amherst.

While his academic results were suitably atrocious, Steinman was 'discovered' by the entrepreneur Robert Stigwood, who signed him to a deal with RSO (and for whom Steinman contributed the song Happy Ending for Yvonne Elimann), and then 'rediscovered' by the legendary Joseph Papp, who became so excited by The Dream Engine that he bought the rights to the show during the intermission of the college performance.

Papp hoped to launch Steinman on Broadway with the show, but was stymied by its explicit sexual content. Instead it had a brief run in Washington DC with Richard Gere in the lead role. "Gere has one of the great rock'n'roll voices, which he won't use, because he feels people won't accept him as an actor if he sings."

Papp kept faith with Steinman, engaging him in a number of projects, including the 1971 Shakespeare in the Park Festival in New York's Central Park. Steinman had began work on More Than You Deserve with the off-Broadway lyricist Michael Weller. By happy chance, the big guy from Texas had just hit New York, too, hot from a run in The Rocky Horror Show and looking for work.

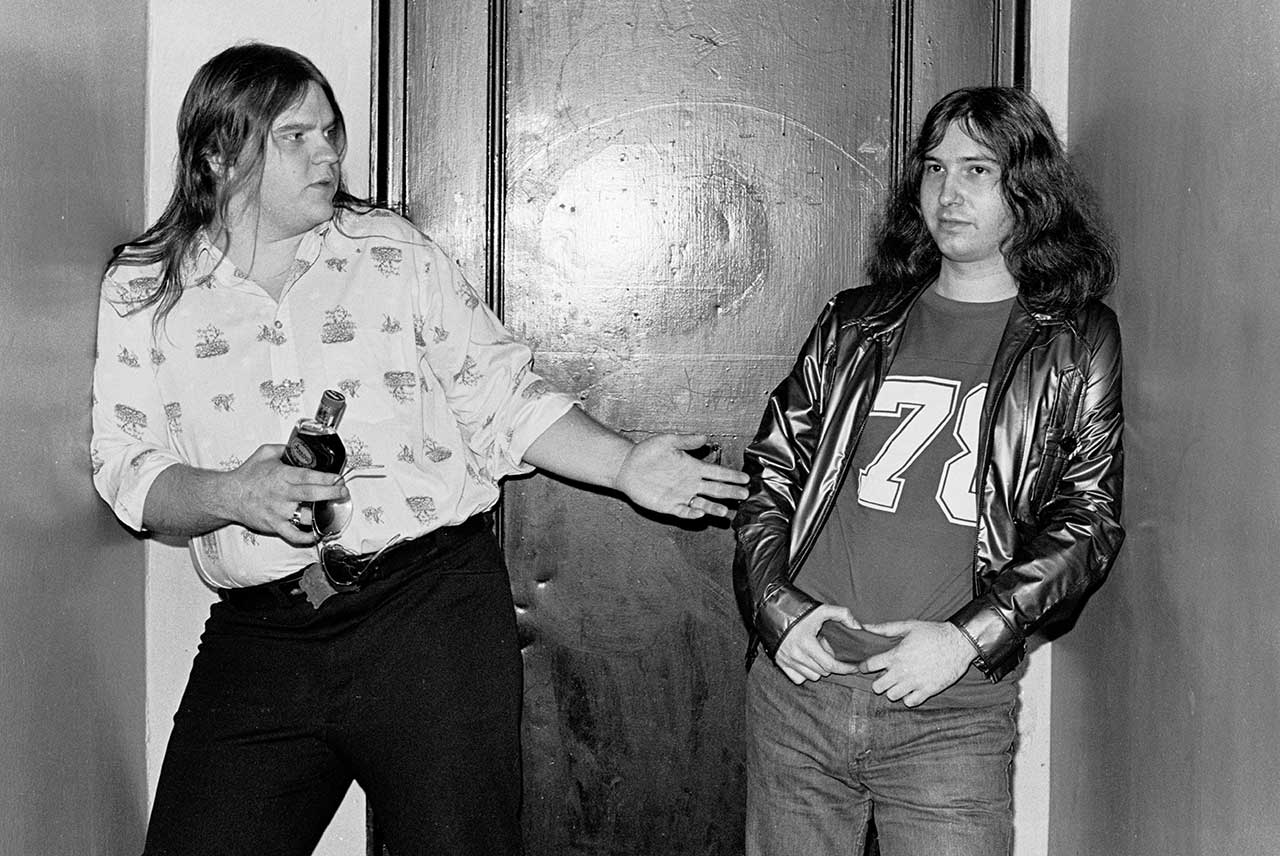

"Meat was the most mesmerising thing I'd ever seen," remembers Steinman. "He was much bigger than he is now, he was fucking huge, and since I grew up with (German composer Richard) Wagner, all my heroes were larger than life. His eyes went into his head, like he was transfixed. [At the audition], he sang "You gotta give your heart to Jesus"… I can seem arrogant at times because I'm certain of things and I was certain of him."

Meat Loaf: "When I first met Jim he was sharing an apartment on 102nd Street with I don't know how many people. His bed was in the kitchen. Its headboard was the refrigerator. I said, 'Jim, what if anyone wants something from the refrigerator?' He said, 'Believe me, no-one does'."

More Than You Deserve enjoyed modest success, but is significant as the starting point for the classic Tonight Is What It Means To Be Young and for the show-stopping title number, which appears on Meat Loaf's 1981 album Dead Ringer.

Steinman returned to another of his lyrical obsessions, Peter Pan, for his next project, Neverland, in 1975, by which time both he and Meat were touring with the National Lampoon show (in which they had replaced Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi). Three of the songs in Neverland – Bat Out Of Hell, Heaven Can Wait, and Formation of the Pack (All Revved Up With No Place To Go) – were exceptional, the pair felt, and Steinman began to develop them as part of a seven-song set they wanted to record as an album.

"I never intended to do music, I didn't think I was a good enough musician. I was gonna do film and theatre, but I figured, 'This is fun, let's do this,'" Steinman said. "I didn't want it to be just a bunch of songs. I wanted it to feel like you were entering a cinematic or complete theatrical environment. No one could deal with it. They couldn't figure out what it would sound like finished."

As he reminisced, Steinman wore an expression somewhere between baffled and amused. He found it almost impossible to 'get' real life. "I never thought of the songs as being personal songs in terms of my own life... but they were definitely personally obsessive songs," he admitted. "They were all about my obsessions. I mean, none of them takes place in a normal world, for me. They all take place in very extreme worlds, very operatic again. The key word is really 'heightened'."

Steinman's imagery was, like The Dream Engine, revved up and testosterone-fuelled. Songs like Paradise By The Dashboard Light, Two Out Of Three Ain't Bad and For Crying Out Loud echoed the textbook teenage view of sex and life: irrepressible physical urges and unrealistic romantic longing, written by a man who'd never been nagged for leaving the toilet seat up.

"I was a teenager right when sex was going from being overly repressed in the early 60's to totally free in the 70's and it was very confusing," confessed Steinman. "Shit, I remember shaking like a leaf the first time I was having sex. Terrified I was doing everything wrong, and a little bit horrified."

The essential innocence of his vision, though, was his saving grace.

"All I can say is that thank God we knew nothing about making albums, because otherwise it couldn't have happened. I wanted to make an album that sounded like a movie."

The process of landing a deal for the completed songs was to prove even more tortuous than the conception, which itself took two years. Steinman and Meat Loaf would make appointments at record companies, and then Steinman would take a seat at a piano and play the entire album, in sequence, while 300 lbs of Meat Loaf sang along. Sometimes Ellen Foley would accompany them to perform the duet on Paradise By The Dashboard Light. Aside from the bizarre spectacle the pair presented, the music was unlike anything anyone had ever heard.

The closest point of reference – and an ironic one given some of the musicians later involved in the recording – was Bruce Springsteen's passionate and epic Born To Run album, released in 1975. Lengthy, piano based songs like Bat… and For Crying Out Loud were echoed in Springsteen's Thunder Road and Jungleland.

After CBS boss Clive Davis rejected the project, Meat Loaf almost cracked. They were saved by the man Steinman has called "The only genuine genius I've ever worked with," the Canadian musician and producer Todd Rundgren. On hearing the Bat… songs, Rundgren claims he "rolled on the floor laughing. It was so out there. I said, 'I've got to do this album…"

Rundgren took the pair to Bearsville Studios near Woodstock in New York State, and brought in bassist Kasim Sultan and Roger Powell (keyboards) and Willie Wilcox (saxophone), who played with his band, Utopia.

In addition, Steinman recruited drummer Max Weinberg and pianist Roy Bittan of Springsteen's E Street Band. But it was one man who was to bring the project together. It was a time for heroes, and Steinman and Meat Loaf had found one.

"One of the most mind-blowing moments in my life," Meat Loaf, said, "was watching Todd Rundgren play the guitar and do it in one take, and one take only. In 15 minutes he played the lead solo and then went back and did the harmony guitars at the beginning. The whole thing didn't take him more than 45 minutes! Then Todd mixed the record in one night. He started at six o'clock and finished about four o'clock in the morning."

Initially, the tapes interested one of Bob Dylan's first managers, Albert Grossman, who took the record to Warner Bros' head honcho, Mo Ostin. Much wrangling ensued, with Steinman and Meat Loaf fearing the record would never be released, when another E Street Band Member 'Miami' Steve Van Zandt (also known as Little Steven and later a star of cult US TV series The Sopranos) got Cleveland International plugger Steve Popovitch to front a deal.

Almost four years in the making, Bat Out Of Hell was finally released by Cleveland International on October 21, 1977. Cleveland International's parent label was Epic Records, and almost everyone there hated it.

Inevitably, the outrageously overblown Bat Out Of Hell inspired extreme reactions.

Jim Steinman: "I describe it as feverous, strong, romantic, violent, rebellious, fun and heroic."

Meat Loaf: "I think Bat Out Of Hell is more real than 95 per cent of the records ever made."

Ellen Foley: "There are just some things that touch an emotional core that I think people are going to want to listen to for a long time. This record is one of them."

Max Weinberg: "I think Bat Out Of Hell will probably last forever."

The album proved the classic 'sleeper'. Six months after its release, the Old Grey Whistle Test took the ambitious step of airing a film clip of the live band performing the nine-minute title track. Response was so overwhelming, they screened it again the following week. As a result, in the UK Bat… became and unfashionable, uncool, non-radio record that became a 'must-have' for everyone who heard it, whether they 'got' Steinman's unique perspective or not.

Eventually every track on the album became a hit single and the album became a phenomenon, selling an estimated 50 million copies worldwide. It was also the most profitable release in history, beating even Michael Jackson's Thriller, which had cost ten times as much to make.

But success came with turmoil. Even Meat Loaf's mighty voice was broken by the touring schedule required and the attendant pressures. As a result, he was unable to record Steinman's Renegade Angel, which Steinman eventually cut himself as Bad For Good in 1981.

This was the period in his life that Meat Loaf now describes as his "darkest hour". Famously, Steinman had spliced together Meat's vocals from separately recorded phrases and one-liners to complete the wonderful Dead Ringer album after the singer had claimed to be experiencing a mental block.

"Yeah, I had a mental block, but not the kind of block you're talking about," Meat told Classic Rock on 1999. "My block was because Bad For Good was trying to be a copy of Bat Out Of Hell. Dance In My Pants was trying to be a copy of Paradise By The Dashboard Light and Lost Boys And Golden Girls was trying to be a copy of Heaven Can Wait.

Afterwards, they split, apparently for good. "I was upset at everyone trying to rush the follow-up out," said Meat, recalling their disagreement. "Jimmy and I had spent four years of our lives putting together Bat Out Of Hell. Yeah, Jimmy wrote, because he was a better writer than I was. But we worked together on those songs. I said, Jim this is not how we did Bat Out Of Hell. We need to sit down and work together. And he just, like, shrugs. And I just lost it. I said, that's it. I went back to the house we were staying in, packed the car, took my wife and split."

The differing characters and expectations had ultimately driven a wedge between the two. Steinman draws a line between Meat the man and Meat the character who sung his songs. But the famous court case that ensued over the album's profits left the singer floundering. In 1983, he was sued to the tune of $85 million by Steinman and former manager David Sonenberg and was forced to file for bankruptcy.

While Steinman's vision continued to provide hits for artists as diverse as Bonnie Tyler, Barbra Streisand, Air Supply, the Sisters of Mercy and even Boyzone, Meat Loaf drifted without him through a succession of half-baked efforts like Midnight At The Lost And Found ('83), Bad Attitude ('84) and Blind Before I Stop ('86).

Ultimately, as we now know, they would reunite for the hugely successful sequel Bat Out Of Hell: Back Into Hell in 1993. It's lead-off single I Would Do Anything For Love (But I Won't Do That) demonstrated that the old magic was still there and the follow-up netted them a genuine fortune as it topped the charts in over 25 countries, but for both, the original would mark a peak of different sorts.

For Meat Loaf, it marked the beginning of his transition from nonentity to huge star. A slimmed down, short-haired Meat returned two years later for the patchy Welcome To The Neighborhood which featured just two Steinman tunes and the inevitable Very Best Of album in '98, but by then he was talking about dropping music altogether and concentrating on successful screen roles in movies like Everything That Rises. During the press tour for the latter, the singer was quietly fuming about having to turn down the chance of starring with Nicolas Cage in a new Martin Scorsese movie in order to be in London to talk to the media.

"Movie critics love me, but rock critics just brutalize me," he told our own Mick Wall. "With Steinman and his manager and lawyer, there's too much baggage. Nobody will let it go and everybody has to have a piece. So it's a shame."

Nevertheless, during the same interview, Meat also told Classic Rock that the possibility of a third Bat Out Of Hell album remained [Bat Out of Hell III: The Monster Is Loose was released in 2006, although Steinman was not involved in the production], although the long mooted idea of turning it into a movie or a Broadway musical was now never likely to occur [the musical version of Bat Out Of Hell debuted in 2017].

"It'd never end up as a stage show," he stressed. "It can't. I mean, it just won't. As for the movie, as much as I've tried to help Jimmy put it up and as much as I've tried to make the film go, it's just too much of a struggle. There's people who wanna do it, but…"

When it was suggested that Steinman felt rancour over being less famous than Meat Loaf, the latter clearly felt there was nothing he could do about the situation.

"Why do you think Jimmy still wears all the gear?" he retorted rhetorically. "It's like, you get U2, you get Aerosmith, you get Steinman. You get these guys, they dress the part. They want to get noticed! Whereas me, I cut my hair, I got these suits. People think I'm a friggin' accountant when I walk in the room now."

Nevertheless, the significance of Bat Out Of Hell continues to loom spectre-like over Meat Loaf's life.

"These two professors who are head of their departments at these Ivy League universities in the States did this psychological test in the US Medical Journal to determine the subject's state of mind," he claimed.

"They've started to use the Bat… album as a sort of Rorschach test. Basically the bottom line is this: if you don't like Bat Out Of Hell, then you have a problem. Now psychologist and psychiatrists all over America are giving it to their patients, having them listen to it and then come back. Now they say that if you know anybody and they don't like Bat Out Of Hell, you'd better be careful – they could snap at any moment. It's a medical fact now, and I see it as my redemption."

For Steinman, Bat Out Of Hell was more than just a spectacularly successful album: it was a validation of his inner life, of his imagination.

"I think it is a heroic record, ultimately, in content and execution," he concludes. "There is a sense of heroism which you definitely don't find in most pop music. Even today, every time I finish a record, I always play it back-to-back with Bat…"

This feature originally ran in Classic Rock 19, in September 2000.