Cream albums: the essential guide

Cream's albums showcased three mercurial talents who blew the stuffy, traditional British blues scene apart and exported the results back to America

“Blues ancient and modern,” was how Eric Clapton described Cream’s music when the trio were launched in an orgy of expectations in the summer of 1966. Bassist (and classically trained cellist) Jack Bruce spoke of “re-writing the blues” while awesome drummer Ginger Baker talked about the “fantastic sound we were all part of”.

Clapton already had impeccable blues credentials, courtesy of his stint with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. Bruce and Baker had arrived from the progressive R&B-based Graham Bond Organisation. The chemistry that these three mercurial talents produced blew apart the stuffy, traditional British blues scene that had demanded faithful note-for-note reproductions of American blues.

Cream took the two-note riff of Howling Wolf’s Spoonful and expanded it from two and a half minutes to six and a half, jamming with an intensity that had not been seen outside jazz. Behind them a host of bands from Fleetwood Mac to Chicken Shack followed them into the breach.

It was the same when they got to America. The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane prided themselves on their musicianship but Cream simply blew them away. They increasingly focussed on breaking America and by their third album, the double Wheels Of Fire in the summer of 1968, they had done so. But they had also broken themselves.

Their volatile mix could not withstand the incessant touring and they broke up after a final show at London’s Royal Albert Hall in November 1968. They had pioneered the changes however. When they started it was all known as pop music. When they finished they were spearheading rock music.

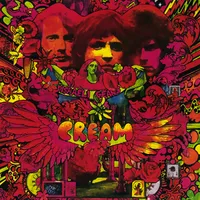

Cream’s raw, dynamic debut, characterised by Bruce’s jazz-influenced bass, Baker’s thunderous rhythms and Clapton’s searing solos.

The group’s deconstructed versions of Spoonful, I’m So Glad and Rollin’ And Tumblin’ have awesome power, while the prototype heavy rock riffs of their self-written NSU and Sweet Wine add another dimension. Now includes their first two singles: Wrapping Paper and I Feel Free.

In 2017 Fresh Cream was issued as a four-disc set with mono and stereo remasters, single and EP remixes, early versions, BBC sessions and a 24/96 Hi Resolution Audio on Blu-ray.

Epitomising the spirit of 1967 from the sleeve to the grooves, Cream blaze their way though a range of material, from the swirling, atmospheric Strange Brew, Dance The Night Away and We’re Going Wrong to the fierce riffs of SWLABR and the grinding wah-wah of Tales Of Brave Ulysses.

Capping it all is the future metal classic Sunshine Of Your Love. Deluxe Edition includes BBC sessions and alternative takes.

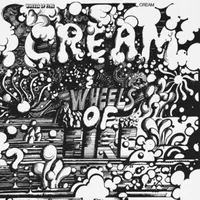

In the studio: the anthemic White Room, the biting funk of Politician and Born Under A Bad Sign, the blues power of Sitting On Top Of The World and the high-flying Those Were The Days.

Live at The Fillmore: 17-minute versions of Spoonful and Baker’s drum solo Toad, plus the concise, blistering Crossroads that crams Cream’s essence into an astonishing 4min 14sec. Released as double, and a single studio album.

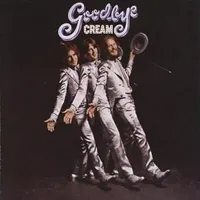

The goody bag at the end of the party, condensing studio tracks and live material from the farewell tour onto one album, and highlighting the schizophrenia at the heart of Cream.

They each have a studio track, and Clapton brings in George Harrison to supply the bridge for Badge, which became a hit single. The live I’m So Glad is nascent grunge. The album gave Cream a posthumous UK No.1.

In 2019 Goodbye was also issued as a 4-CD set featuring live shows from their farewell tour at Los Angeles, Oakland, San Diego and London’s Royal Albert Hall.

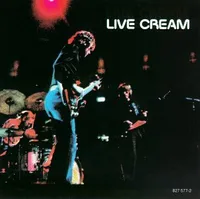

Four songs from their Fresh Cream debut album (which formed the bulk of their live set throughout their career), with NSU weighing in at a monstrous 10 minutes and Sweet Wine a turgid 15 minutes.

Meanwhile, Sleepy Time Time and Rollin’ And Tumblin’ are modestly kept to under seven minutes. There’s also a studio version of Hey Lawdy Mama – the song that got psyched into Strange Brew on Disraeli Gears.

A last trawl through the 1968 live tapes box (sadly there are no official Cream recordings from 1967) that comes up with uninspired versions of Wheels Of Fire tracks including White Room and Deserted Cities Of The Heart.

It’s rescued by a heavy-metal Sunshine Of Your Love and the howling, 13-minute instrumental Steppin’ Out that Martin Scorsese used for the memorable climax of his 1973 movie Mean Streets.

A four-CD set, with every track from their six albums along with non-album singles, rejected tracks for the first album, intriguing out-takes from the second, a couple of unreleased songs resurrected for Bruce’s solo debut, Sunshine Of Your Love recorded for the Glen Campbell TV show, and a Falstaff beer commercial.

22 tracks laid down between late 1966 and early 1968, and catching Cream on the spot during their most creative period.

Only two tracks clock in at more than four minutes, and some are even shorter than the studio album versions, but it’s amazing how inventive they can be within such confines. More illuminating than either volume of Live Cream – and less likely to cure your insomnia.

Royal Albert Hall London May 2-3-5-6 2005

Thirty seven years after their farewell concert at the Royal Albert Hall Cream were reunited at the same venue. They’d spent three weeks reconnecting with themselves and the music, working out how to present their legacy without relying on nostalgia.

This time around the songs were shorter, the solos more concise and their playing now had a maturity that gave the songs a different kind of sparkle. Finally the legend could be laid to rest.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.