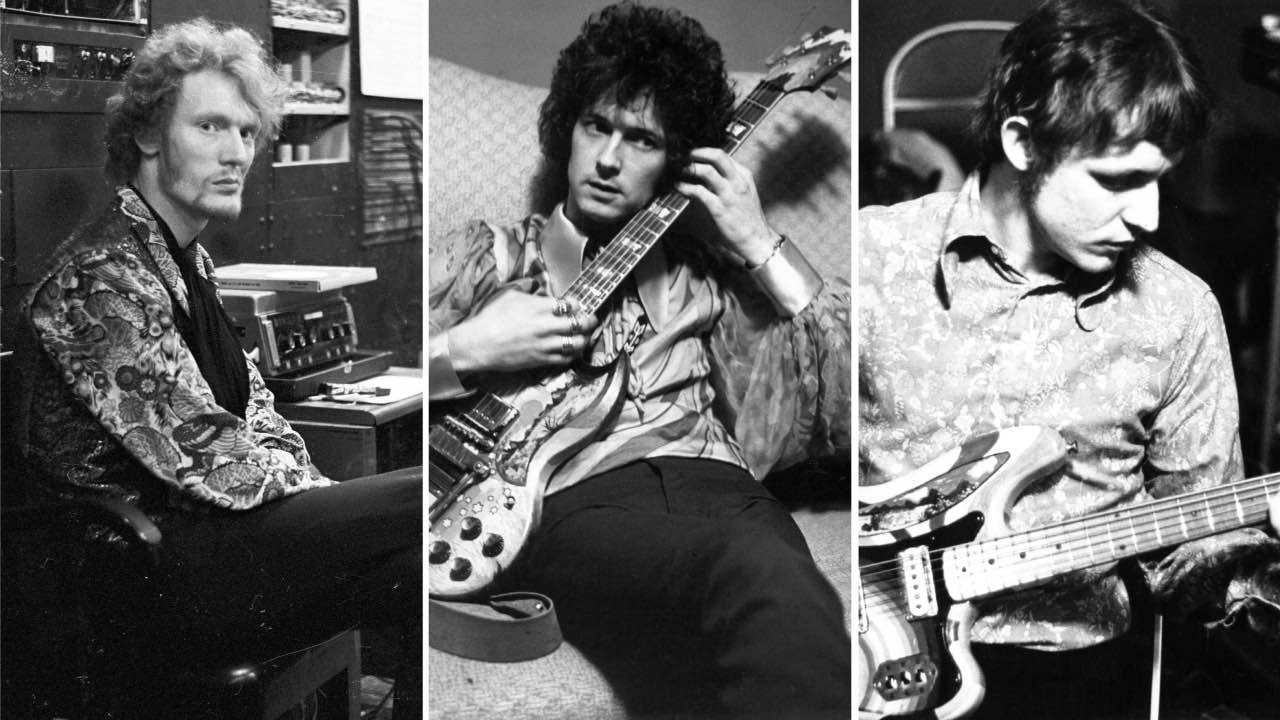

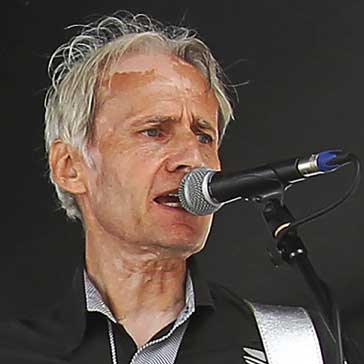

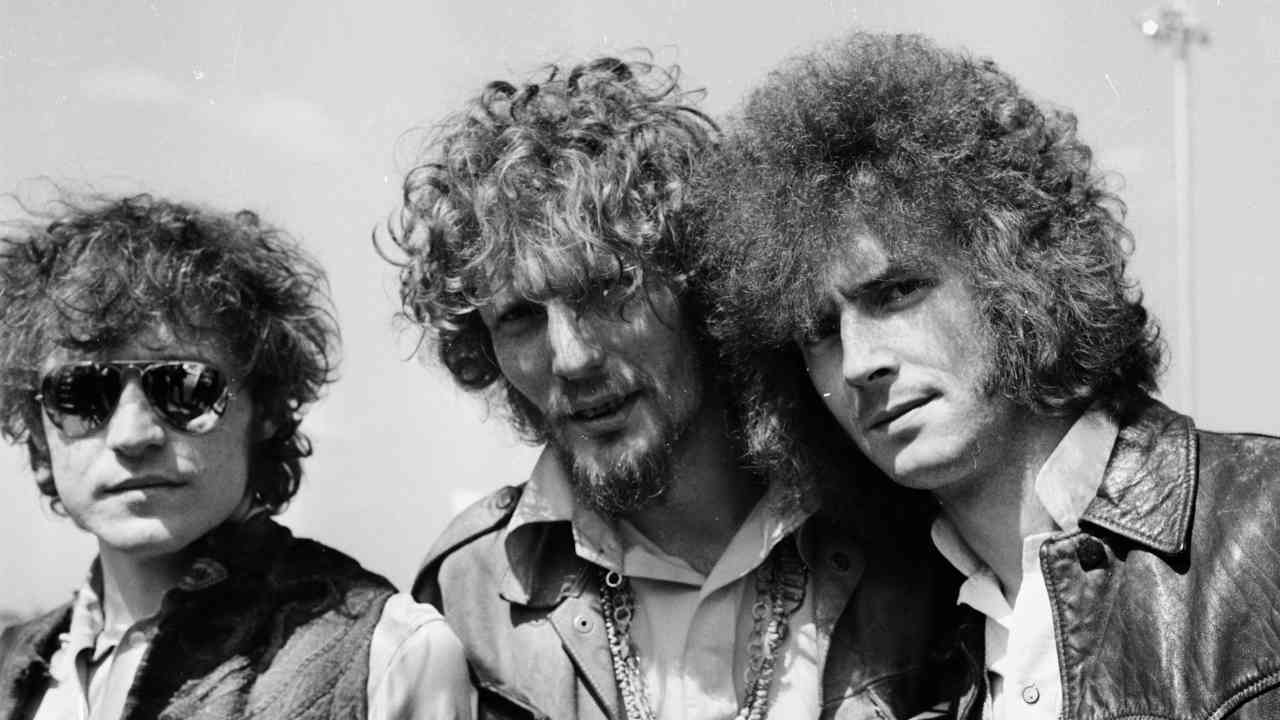

If ever a record stood at the crossroads of rock, it was Disraeli Gears, the second album by Cream. Written, recorded and released in the watershed year of 1967, it was a collection that linked the legacy of the blues to the onward rush of psychedelia. Made in America, yet unmistakably British in sound and sensibility, it captured epic studio performances by Jack Bruce, Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker at the peak of their powers as a group.

With its iconic cover artwork by Martin Sharp, featuring the granite-faced trio staring out across a garish red and pink dreamscape of irradiated flowers, peacocks, galloping horses and amorphous swirls, Disraeli Gears became a touchstone recording of the 1960s counterculture. A massive worldwide hit, it propelled Cream to international stardom and remains the trio’s finest hour. “It’s nice that people remember that album,” Jack Bruce, who died iin 2014, told Classic Rock in 2008.. “It was a lot of fun.”

A lot of very quick fun, to judge by today’s standards. The entire album was recorded in just five days, from May 11 to May 15, at Atlantic Studios in New York. “We worked very fast,” Bruce said. “We didn’t know that you were meant to take months and years to make an album. A lot of the tracks were first and second takes.”

Although Cream had already enjoyed UK chart success with their debut Fresh Cream, released in December 1966, the band had actually been together less than a year when they started recording Disraeli Gears, and had only just signed an American deal with Atlantic Records. The head of the label, Ahmet Ertegun, had assigned them a young American, up-and-coming producer, Felix Pappalardi (who would later go on to become the bass player in Mountain) and the experienced sound engineer Tom Dowd.

“Musicians were not very studio-savvy in those days,” Bruce said. “We weren’t knowledgeable at all about the art of recording. I think the sound of the album, you’d have to give most, if not all of the credit to Tommy Dowd. He was a genius of an engineer.”

Ertegun looked on Clapton as the natural leader of the group. Being a traditional record company man, Ertegun was suspicious of a set-up which was designed to split an audience’s attention three ways as opposed to focusing it on one person at the front. So although Bruce and Clapton had shared the vocals on Fresh Cream, Ertegun initially encouraged Pappalardi to push Clapton forward as the lead singer.

“I think Ahmet [Ertegun] really admired Eric,” Bruce said. “He often talked about that. And he had this strange, garbled version about how he discovered Eric and Cream or something. All complete nonsense. But they definitely thought Eric was more marketable, and there was a big move to get Eric to be the frontman and me just to be the bass player.”

Baker was not impressed with this scenario either. “At the start Cream was mine,” he said. “I took a drop in salary to start Cream, whereas Jack and Eric took a step up. Cream was always my baby.”

A power struggle to be the frontman in this trio of giant egos was not in anyone’s best interests, and as things turned out it was Bruce who eventually had most of the songwriting and singing credits on Disraeli Gears. But to begin with it was all about Clapton, who was prompted to take the lead vocals on the album’s opening track – and first single from it – Strange Brew.

The track began life as a cover of an old Albert King number called Lawdy Mama. Pappalardi took the tape of the backing track home after the first day of recordings and returned with it the next day, as Clapton recalled, “having transformed it into a kind of McCartneyesque pop song, complete with new lyrics and the title Strange Brew”. Bruce accepted that the riff is still “a bit Albert King” but preferred to think of it as “a tribute” rather than a rip-off.

Booker T Jones, the legendary session keyboard player, was one of several distinguished musicians who dropped in to Atlantic Studios during the course of the Disraeli Gears sessions, and Bruce, for one, had cause to be grateful for his support over the matter of Sunshine Of Your Love, a song Bruce co-wrote with Clapton and the lyricist Pete Brown.

“I was very excited by the song,” Bruce said, “But Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler [Atlantic’s head of A&R] weren’t at all impressed by it. Jerry called it ‘psychedelic hogwash’. I was really angry, cos I knew that this was a special thing. Luckily Booker T was in the studio that day, as was Otis Redding, and it was actually Booker T who said to Ahmet: ‘That’s a huge crossover hit.’ He [Booker T] could see it. When it became the biggest-selling single in the history of Atlantic, I think Ahmet finally saw it too.”

With its grinding, step-down riff, war-toms drum beat and dynamic vocal interplay between Bruce and Clapton, Sunshine Of Your Love is arguably the most universally recognised and influential number that Cream ever recorded. The song which launched a generation of heavy rock bands in its wake began life in Bruce’s flat in Hampstead, London.

“Pete and I had been working all night trying to come up with some songs,” Bruce said. “I just picked up my double bass and looked out the window and the sun was coming up. And I just started playing the riff of Sunshine Of Your Love. And Pete looked out the window and said: ‘It’s getting near dawn,’ and he wrote it down, just like in one of those really cheesy biopics. So we played it, and then Eric came up with that really nice turnaround part: ‘I’ve been waiting so long…’”

But Disraeli Gears was not just about the heavy riffs in life. World Of Pain, written by Pappalardi and his wife Gail Collins, was brought in at about the same time as Strange Brew. “It is along the lines of some of the more melodic, less bluesy things that I was writing,” Bruce said. “I thought it was an interesting song.”

Dance The Night Away was another of the more melodic songs, all soaring harmonies and jangling 12-string guitars. “This was a nod towards the Byrds who I really loved at the time,” said Bruce, who wrote the song, again with lyrics by Pete Brown. Brown, a poet who was part of the Liverpool scene in the 1960s, wrote the lyrics to many Cream songs. As well as Dance The Night Away and Sunshine Of Your Love, his contributions to Disraeli Gears included the words to the bizarrely-titled Swlabr (an acronym for She Walks Like A Bearded Rainbow).

If Brown’s trippy flights of fancy about living with golden swordfish and wandering through a wonderland of fantastic colours sound a little quaint in retrospect, they certainly resonated at the time, as did cover artist Martin Sharp’s lyrics to Tales Of Brave Ulysses.

We’re Going Wrong, another of the standout tracks on the album, was written by Bruce and sung by him in an extraordinary, high-pitched “head” voice (“not falsetto” according to Bruce) that was one of the most distinctive elements of Cream’s sound. “Musically, what I always wanted to go for with Cream was to have really heavy instruments with really light vocals,” Bruce said. “Also I liked the idea of the two voices, both in the same register, so that you can’t actually distinguish who is singing what.”

There is also a third voice on Disraeli Gears, which is all too easy to distinguish. Ginger Baker took the lead vocals on his own composition, a rather wobbly dirge called Blue Condition. Asked years later whether he was proud of his singing on Disraeli Gears the drummer responded: “No. I can’t stand my singing. I think it’s fucking awful.”

Bruce, however took a more charitable view: “Well, it’s Ginger, isn’t it? It’s part of the tradition of The Beatles always having a song by Ringo on their albums. It’s probably not the first track you head for. And I don’t think we ever did it live, more’s the pity. But who else could sing like that? Ginger is a rabid sentimentalist. And you can quote me on that.”

The album ends with an unlikely performance of Mother’s Lament, an old music-hall number, sung by Clapton and Baker in a broad Cockney accent; Bruce, who speaks with a distinctive Glaswegian brogue, kept clear of the mic on this occasion.

“I ain’t no Cockney, mate,” he said in 2008. “I was playing the old joanna [piano] on that one. I think it was just our way of saying: ‘This is us. We’re not trying to be what we’re not.’ That was an important part of our attitude. At the time, you had two kinds of people that were playing the blues. You had the John Mayall approach, which was to recreate a Chicago blues sound. But my idea, and I discussed this with Eric quite a lot, was to actually take the blues and apply it to what we were.”

An updated version of Blind Joe Reynolds’ Outside Woman Blues, imported and sung by Clapton, and featuring his creamy ‘woman’ guitar tone was as close to an ‘authentic’ blues song as the album got. “All sorts of singers from Robert Johnson onwards, have used those kind of lyrics,” Bruce said.

But any idea that Cream were some kind of blues revivalists was dispelled by the forceful originality of the songwriting elsewhere on the album and the many highly distinctive performances on a collection that has most surely stood the test of time.

Was Disraeli Gears the best Cream album? “Yes, probably,” Bruce said. “There’s better individual tracks on some of the other records, maybe, but I think it hangs together as a bunch of songs.”

Published in Classic Rock 127