Creedence Clearwater Revival were about to enter a storm. Seventy-two hours after touching down in London in April 1970, ahead of their first European tour, their press conference was overshadowed by shock news of The Beatles’ split. Reporters, TV crews and distressed fans were gathering in numbers outside Beatles label Apple’s offices on Savile Row; newspapers scurried to prepare competing headlines.

The next day’s NME carried an oddly prophetic interview with CCR leader John Fogerty, conducted en route to customs inspection at Heathrow airport. He explained that his band were now experiencing what The Beatles had gone through a thousand-fold, their records selling in huge quantities worldwide.

“Of course,” he added, “we can never ever hope to emulate the impact made by The Beatles. Nobody can.”

His modesty was understandable. But it transpired that Fogerty was somewhat underplaying the CCR effect. In a little over a year, they had scored half a dozen Top 10 singles and three platinum-selling albums in their native US – a run that was about to eclipse the Fabs in terms of sales. CCR were fast becoming the biggest band on the planet.

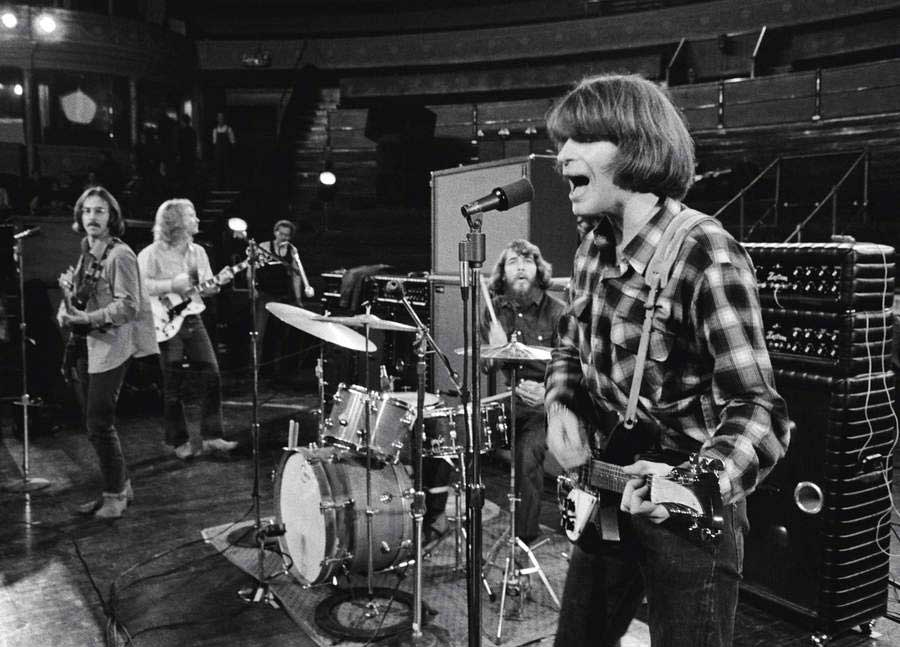

On the night of April 14, 1970, they set out to prove it. Four days on from the Beatles news, CCR played the first of two sell-out shows at London’s Royal Albert Hall. It was an unmitigated triumph, the band powering through a set with explosive force, twisting the basic tenets of rock’n’roll into their own distinct brand of Californian voodoo.

“Right around that time we really started to come into our own,” Fogerty reflects today. “You start to hear that confidence and swagger in the way we perform. That performance was pretty doggone good, pretty solid and strong and full of energy. I was a kid from El Cerrito and, as of two years before that, had never been anywhere. Suddenly I’m touring the States for a year and then experiencing all the musical touchstones of Europe.”

“It was an honour to be there, knowing that we get to play in The Beatles’ house, the Royal Albert Hall,” says voluble CCR drummer Doug Clifford. “I’m an athlete, and always have been, so I’m competitive about when I play to win. I wanted us to do the best possible job. We all felt that way, I’m sure. And I think we pulled it off. I’m pretty sure I saw Eric Clapton [at the RAH], and I think I saw Paul McCartney. Just knowing where we were and what we were doing was a thrill.”

The gig finished with CCR’s customary longform closer Keep On Chooglin’, after which the band received a 15-minute standing ovation.

More than half a century later, the just-released At The Royal Albert Hall captures the show in all its verve and glory. It’s accompanied by a documentary, Travellin’ Band: Creedence Clearwater Revival At The Royal Albert Hall, which features the entire show. (CCR’s The Royal Albert Hall Concert, released in 1980, was reportedly from a concert at Oakland Alameda County Coliseum.) Narrated by actor Jeff Bridges and directed by Bob Smeaton, who was responsible for The Beatles Anthology TV series, it represents CCR at their most formidable.

“In terms of the performance, what I’d forgotten was the energy and the passion,” marvels bassist Stu Cook. “I think we went there with the intent to take no prisoners. When I saw the performance, I was kind of surprised by the intensity of it. Woodstock was great, but it was incredibly chaotic and late and stressful. I think that first time we played the Royal Albert Hall was probably the pinnacle for me. If I could relive a night, that would be it."

Despite suggestions to the contrary, CCR were no overnight sensations. Their success was the product of diligence, tenacity and sheer staying power. Initially forged in the suburbs of Northern California in 1959 as an instrumental trio, The Blue Velvets, things first started to move with the arrival of Fogerty’s elder brother Tom on rhythm guitar and lead vocals.

Billed as Tommy Fogerty & The Blue Velvets, the band released three unremarkable singles on a local Oakland label between 1961 and ’62, grounded in the music they’d grown up with: 12-bar blues, rockabilly and doo-wop. But the British Invasion, spearheaded by The Beatles, brought a change in direction.

“These great British groups took over where America left off,” Clifford says. “Rock’n’roll was an American phenomenon, but it had got kind of boring. And the Brits said: ‘Well, we think it can be saved and we like it. We’re going to do it.’ And they did.”

It brought a change of label too. In May 1964, three months after The Beatles’ game-changing first appearance on US TV on The Ed Sullivan Show, The Blue Velvets auditioned for the San Francisco-based Fantasy Records, and were duly snapped up. Label co-owner Max Weiss, seeing an opportunity, encouraged the quartet to embrace the UK beat boom on early singles like Don’t Tell Me No Lies and You Came Walking.

Weiss insisted on releasing these under the name The Golliwogs, in an appallingly misguided attempt to make the band sound British. They made no impact. A further handful of singles suffered a similar fate. 1966 saw the emergence of John Fogerty, now lead singer, as the band’s dominant force on Fight Fire and the howling psych-rock of Walking On The Water. Perhaps thankfully, this run of failure was interrupted by a spell of National Service for Clifford and the younger Fogerty.

On his return in 1967, Fogerty delivered his strongest song to date. Porterville was a pre-echo of the classic CCR sound, conceived on the parade field in the Army Reserve unit.

“During all that marching I would get delirious, and my mind would start playing little stories,” he told Creedence biographer Hank Bordowitz. “They all seemed to be sort of swampy and southern, in the woods and with snakes; Br’er Rabbit, Mark Twain, a great old movie with Dana Andrews and Walter Brennan called Swamp Water. So I ended up writing Porterville while I’m stomping around in the sun.”

Released as the final Golliwogs single, in November ’67, Porterville had Fogerty handling production as well (bizarrely credited as ‘T. Spicebush Swallowtail’). Afterwards, the band rang the changes once more. Coinciding with Fogerty’s decision to sack “sappy love songs” in favour of narratives, the foursome took on a fresh moniker.

Credence Newball, a good friend of Tom Fogerty’s, provided the initial impetus. A TV ad for a brewing company (who prided themselves on “clear water”) gave them added splash, while ‘Revival’ was an indicator of their commitment to the cause, a renewed statement of intent. Porterville was reissued as Creedence Clearwater Revival’s debut 45 the following January.

Perversely, however, it was a cover that reversed the band’s fortunes. A swamp-rock version of Dale Hawkins’s Suzie Q was sent to progressive Bay Area radio station KMPX. The track was the kind of open-ended attack – eight-and-a-half minutes spread across both sides of a single – that chimed with the fluid psychedelia of the times. But it was actually a product of rigorous discipline and endless rehearsals; CCR were no jam band. Instead, and unlike many of their San Francisco contemporaries, some of whom mocked them for their straight-up aesthetic, they were a totem of rootsy economy.

“Our peers laughed at us, called us the boy scouts of rock’n’roll,” Clifford told West Virginia’s Herald Mail in 2015. “They said we’d never make a thing out of the music that we were playing, said we were not cool, not hip like they were. And it was kind of funny.”

Suzie Q stalled just outside the Billboard Top 10 in the autumn of ’68. By then Fantasy had seen enough to warrant an album. CCR’s self-titled debut did well enough that year, peaking at No.52 in the US, although its other standout song (besides Porterville) was a further cover: a dynamic revival of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’s old creep-show classic I Put A Spell On You.

CCR may have finally found some traction, but they were still a band in search of an identity. It was a challenge that John Fogerty resolved to meet head on.

“I had kind of taken stock at the end of 1968, and looked around at my situation,” he remembers. “We had a hit with Suzie Q, but also, at least to my way of thinking, I realised it was kind of a novelty hit. It didn’t necessarily announce a whole big career in an important cultural turn. I didn’t have a manager, didn’t have a publicist and we were on a very tiny jazz label. I said: ‘Man, I’m going to just have to do it with music.’ And I gave myself that directive and Istuck to it. I figured I had to do it, otherwise it wasn’t going to happen.”

It didn’t look like much from the outside, but the vacant garage warehouse at 1230 5th Street in industrial Berkeley, just a few blocks over from the interstate, was Creedence’s hothouse. Thanks to John Fogerty’s demanding work ethic, the band rehearsed there almost daily. It was enough for Doug Clifford to refer to it as The Factory.

In the preamble to the Royal Albert Hall show, Bob Smeaton’s film offers a rare glimpse of life inside the rehearsal space.

“We had a smaller factory in Doug’s backyard at first,” Stu Cook explains. “It was just a little tool shed, and we managed to stuff us and our small amplifiers and a drum set in there once the lawn mower and brooms and rakes were all taken out. And that’s where we went every day from ten until two or three in the afternoon.

“When we got enough money where we could actually lease a proper rehearsal space, then it became the real factory,” he continues. “It was basically just a large warehouse-type building with a couple of floors, and all the way in the back is where we carpeted and put up the blue velvet drapes, turned that red carpet down and turned it into The Factory.”

“It was a great place to be,” Clifford adds. “We had our music area, but at the same time we had a basketball hoop at one end of the space and ping-pong tables and foosball tables. It was kind of our home away from home. We were working in there, all trying to achieve the same goals, all of us in our different roles. It was a very productive place to be.”

The Factory was where CCR became a proper band, refining their technique and locking in as an extraordinarily tight unit. They reached deep into the history of rock’n’roll – hard-charging blues, R&B, swampy soul, a little country – to fashion what Fogerty once called “a corruption of what has happened before”, made fierce by a burning intensity.

As the quartet progressed, so did Fogerty’s songwriting. He may have been a Californian kid, but his chosen milieu was the Deep South and its attendant mythology. The region’s psycho-geography, and rich storytelling traditions, lent themselves to his new songs. Proud Mary, released in early 1969, was the first manifestation, written two days after Fogerty was discharged from the National Guard. It told the tale of a jaded city boy who leaves it all behind to hitch a ride ‘on a riverboat queen’, the Mississippi paddle steamer of the title.

“One of my favourites that Leiber and Stoller wrote was a Coasters song called Idol With The Golden Head, because it was so colourful and kind of a complete story about an event,” Fogerty explains of his immersion in narrative-driven pieces.

“Another person very much like that is Chuck Berry. All his songs seem to tell a story with pictures. Bo Diddley had a song called I’m Bad and he talked about knocking some guy’s legs out of place. Or Who Do You Love?, where you had a ‘chimney made out of a human skull’ and a ‘cobra snake for a necktie’. Pretty graphic and scary imagery for a middleclass white boy. And very exotic too. Those were things that showed you the possibility of just using your imagination.”

Driven by its freedomriding gospel motif ‘Rollin’, rollin’, rollin on the river’, Proud Mary spoke to something timeless within the American psyche. The single became CCR’s first million seller, stalling just shy of the No.1 spot in the States and going Top 10 internationally.

Another single, Bad Moon Rising, another instant classic, followed in April. It lifted Scotty Moore’s guitar lick from Elvis Presley’s I’m Left, You’re Right, She’s Gone, and Fogerty sang of a looming apocalypse, stuffing the song with ruinous images of hurricanes, floods and earthquakes. Its ringing rhythm and upbeat melody provided a delicious contrast.

Like its predecessor, Bad Moon Rising peaked at No.2 on the Billboard chart, although it topped charts elsewhere, most significantly in the UK. Eventually it also followed Proud Mary into the lexicon of popular music, inspiring covers by Jerry Lee Lewis, Bruce Springsteen, Bo Diddley, Nirvana and many more down the years.

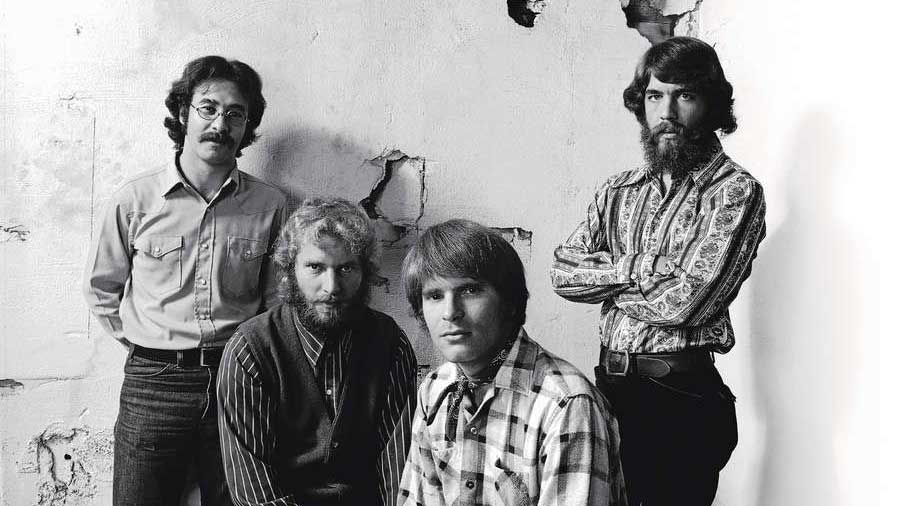

Creedence Clearwater Revival ascended steeply. Bayou Country, the first of an incredible three studio albums in 1969, was a major hit at the turn of the year. It drew much of its symbolism from a fetishisation of the American South. As did its follow-up, Green River, released in the first week in August. The band appeared on the sleeve posed in a dappled glade, like backwoodsmen reluctantly coaxed into the open.

The immaculate title track, another huge hit single, played directly into the same idea, introducing characters such as Old Cody Junior against a backdrop of catfish, bullfrogs, and barefoot girls dancing under the moon. But Fogerty was pulling obliquely from his own childhood, transposing family visits to a Sacramento Valley creek on to an imagined bayou. Green River was the name of a favourite lime syrup. Fogerty never seemed to rest. Songs poured out of him at an astonishing rate, the product of extreme focus and self-will.

“I was really busy, but I liked that,” he recalls. “I was almost addicted to that. It might be some form of a drug produced naturally, like endorphins when you’re jogging. The best part for me was sitting down and trying to write a song and maybe not coming up with anything right then, but at some point, pretty quickly, coming up with a song that wasn’t there before. And it was all such a sort of mysterious process.”

As Creedence’s star continued to rise, demand grew. In between recording sessions, rehearsals and American dates, they swiftly became staples on the burgeoning festival circuit. They played to 200,000 people at the Newport ’69 Pop Festival in June, on a bill that also included the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Eric Burdon and Jethro Tull, among others. Within weeks they’d appeared at major festivals in Atlanta, Denver and Atlantic City.

“It was a rocket ride, definitely,” says Cook. “Once the start button had been pressed, we might have thought we had some control over it. I guess we had a modicum of control day to day, but the larger arc of our career was pretty much out of our hands.”

CCR were also one of the first acts to sign up for the Woodstock festival. As the hottest band in America, Cook believes they were used as bait to lure others. Their planned Saturday night headline slot didn’t quit take place, as it turned out, due to bad weather and technical difficulties throughout the day. With the schedule already running late, CCR instead took to the stage after midnight, following the Grateful Dead.

“I think we did connect with the crowd,” Cook suggests. “It was hard to tell. The audience had just suffered through the worst day of probably most of their lives with the rain, mud and lack of food, just the whole thing, the overcrowding. But they were apparently making the best of it, so it was up to us to do that as well.”

John Fogerty, however, felt that CCR underperformed, leading to his insistence that the band were omitted from both the Woodstock album and Michael Wadleigh’s subsequent film.

In the meantime, Creedence’s hot streak continued. Fogerty had two new hit gems that appeared on a double A-sided single in October: Down On The Corner and Fortunate Son. The two couldn’t have been more different. The former was a funky feelgood tune, freighted with autobiography, about a struggling four-piece (Willy And The Poor Boys) jamming on street corners.

Fortunate Son was a raging commentary on elitism, reflecting the widening schisms in American society due to the ongoing Vietnam War. Fogerty was incensed that sons of the affluent political class were allowed to dodge the draft, while ordinary men were shipped off to South East Asia in their thousands. It remains one of his greatest songs.

Both tracks appeared on the Willy And The Poor Boys album a month later. It was another huge success, selling half a million copies within six weeks. Rolling Stone hailed CCR as the Best American Band. It was reward for an almost impossibly productive year.

“John’s theory was that if we’re ever off the charts, we’ll be forgotten,” says Clifford. “The industry tells you don’t put a single out unless you’re releasing an album with it. But we did that several times, to have something on the charts at all times, and that’s how we did it. And it didn’t seem to hurt our album sales at all. Not only did we do three albums in sixty-nine, but we also toured behind all three and some other things too, like Woodstock. We were at warp speed, but we were always straight and sober when we worked. We couldn’t have done it otherwise.”

The advent of a new decade seemed primed for Creedence. They started with a habitual flurry, releasing another double whammy 45 in January 1970. Travelin’ Band was Fogerty’s exuberant homage to the rock’n’rollers who’d first inspired him: Elvis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry. The flipside, Who’ll Stop The Rain, was more contemplative, a politically pointed song about failed promises and dashed ideals. It was another platinum seller across the globe, and CCR toasted its success with a hometown show at Oakland Coliseum at the end of the month.

By April, with the Willy And The Poor Boys album peaking in the UK Top 10 and two fresh classic singles in the shops – Up Around The Bend and Run Through The Jungle – the band set out to conquer Europe. The eight-date trip involved sold-out gigs in France, Germany, Holland, Denmark and Sweden, with the show at London’s Royal Albert Hall undoubtedly the most prestigious.

“For me, performing live was the best part,” states Fogerty. “Born On The Bayou was pretty good to play; I loved Keep On Chooglin’ too. I also always loved Suzie Q. Those were songs where I got to stretch out a little. It just seemed like everything was working out well.”

The only thing that could stop Creedence, it seemed, was themselves. Director Bob Smeaton points out that: “When those guys walked off the stage at the Royal Albert Hall they were a band of brothers. Tight as friends and tight as a band.”

But within the group, cracks had already started to form. John Fogerty’s iron grip on the band had been evident in his decision to veto their inclusion in the Woodstock album and film. Now, with a full house at the Albert Hall screaming for more, there was another autocratic call.

“We got a fifteen-minute standing ovation from the British crowd and we didn’t go out and do an encore,” Doug Clifford rues. “That was one of the things that I thought was John’s type of leadership, where you punish instead of helping to change the situation or make something better. It was disingenuous. John does encores now, but that was something he took away from the band.”

Creedence Clearwater Revival would reach their commercial peak in the summer of 1970 with their fifth album, Cosmo’s Factory, named after the band’s rehearsal space. It was compounded by another one, Pendulum, in December, by which time there was real dissension within the band. While Stu Cook, Doug Clifford and Tom Fogerty wanted more of a say in the studio, John, the younger Fogerty, stood firm. By early 1971, Tom had quit. A year later, Creedence were done completely.

The story of CCR’s fall-out and collapse is a whole other tale. Ultimately, they’re a band best celebrated rather than mourned. As the At The Royal Albert Hall album proves, theirs was one of the defining sounds of the counter-cultural era, even if they actually occupied a place somewhere closer to the popular culture.

“We were number one in the world in record sales in 1969 and 1970,” says Clifford, still immensely proud of the band’s many achievements. “We were the first band to outsell The Beatles and to take their place. In fairness to The Beatles, their career was starting to fade and go the other way and ours was going up like a rocket ship. But we wanted to be number one. That meant a lot to us.”