As some prog giants fell by the wayside or began pondering an uncertain future, the arch, intelligent pop of Supertramp, 10cc, Roxy Music and more helped fill the void.

It’s become a cliché, but is still regarded by many as being true. Punk undermined progressive rock, and brought bands such as Yes and Genesis to their knees. However, a year before punk began its rise in 1976, the progressive world was already showing a natural ability to adapt and change to prevailing circumstances.

“I honestly can’t think back and feel punk hit bands like us too badly,” recalls 10cc’s Graham Gouldman. “But in 1975, ourselves, Roxy Music and Queen were making an impact.”

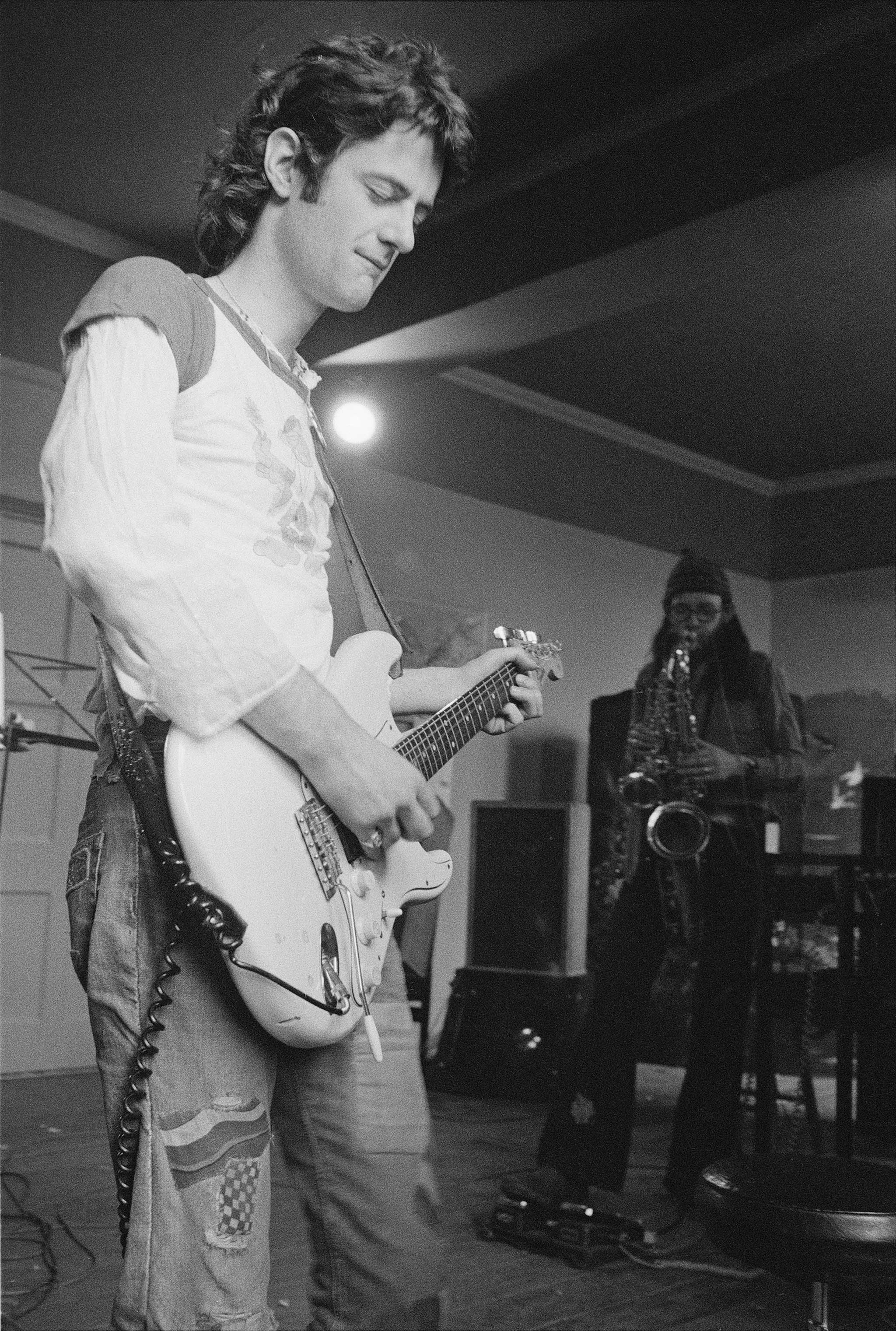

Above: Phil Manzanera of Roxy Music chilling at home, June 18 1975.

Looking at what this year meant musically, one first has to appreciate that it was a time of change in the wider socio-political context. The divisive Vietnam War finally ended; the ramifications of the Watergate Crisis reached a crescendo, with many of those directly involved being given prison sentences; Margaret Thatcher was elected leader of the Conservative Party, and Microsoft was founded.

In many respects, this was the year which laid the foundations for a newer, more contemporary world. And it will come as no surprise that progressive rock reflected this by going through its own evolutionary process. Established bands including Pink Floyd, Yes, ELP and Genesis were each, to a greater or lesser extent, going through upheavals. Floyd released Wish You Were Here, the follow-up to their worldwide hit The Dark Side Of The Moon, but the relationship between Roger Waters and his bandmates was now becoming increasingly strained. Yes had released Relayer the previous year to a mixed reception and had taken a break while their members all made solo albums; ELP went on hiatus and Genesis were now uncertain what lay ahead after frontman Peter Gabriel quit.

Above: ELP in ‘75.

“We didn’t know if there was any future for us,” says ex-guitarist Steve Hackett, recalling the mood in the Genesis camp. “Our star had gone, and none of us were convinced we could carry on. It was a really worrying period for all of us.”

What this meant was that the acknowledged progressive rock elite, and the legacy they’d created, were no longer quite the artistic and commercial force they’d been. The rise of art-rock was also happening, as Graham Gouldman explains.

“I wouldn’t say that we were close musically to Roxy or Queen,” he ventures. “But we did have a lot in common with them. In terms of the way we wrote songs and our dedication to getting the best production. At the time, 10cc never thought of ourselves as part of any significant movement. We weren’t aware of what everyone else was doing, because all we concentrated on was making music in our own way. We thought of what we did as being ‘10cc’, nothing else. So, from that viewpoint, we weren’t leading a great crusade to take intelligent music into a modern era. But if we were part of a movement with bands like Queen and Roxy Music, then I’m grateful. Being compared to these quality acts is a massive compliment to us.”

Supertramp’s woodwind player John Anthony Helliwell has no doubt that there were changes happening in the progressive music world, and Supertramp were a crucial part of what was going on.

“I do feel ourselves, 10cc and Roxy Music were all connected, in that we were making what was sophisticated pop music. I would never use the word ‘pompous’ about what bands like Yes and Genesis had done, because I’ve too much respect for them, but let’s just say we avoid those complicated time signatures they had made their trademark.

“All of us involved in the aforementioned bands had come out of the late-60s touring circuit,” he continues, “so we brought our own experiences to the mid-70s success we enjoyed. And I believe it was genuinely progressive because we brought new influences into what we did. But none of us we exactly friends. We didn’t hang out with, say, 10cc. In fact, they rather upset our drummer Bob Siebenberg when one of those guys rudely criticised him in an interview. Bob then referred to them as ‘10csick’! But we appreciated their symphonic sound, the multiple vocals and their overall quality.”

Guitarist Phil Manzanera, meanwhile, views 1975 as actually being a mixed bag for Roxy Music. Although the band enjoyed enormous success, it also marked the end of a constructive period, rather than the birth of a new one.

“We hit our stride in 1975 with the Love Is The Drug and Both Ends Burning singles, and the subsequent tours of the UK, Europe and USA,” he says. However, it was also the end of three strenuous years of ascent, and the cracks were appearing, which led to the first separation, one that lasted two years.”

In contrast, 10cc were reaching new heights of artistic endeavour, as represented by ’75’s The Original Soundtrack album, which featured the band’s biggest hit, I’m Not In Love.

“We didn’t think anything of that song when it was recorded,” Gouldman admits. “Sure, we liked it, but none of us thought it could be a hit single. But when we started to play it to other people – family, friends and people from the label, Mercury – they were the ones telling us it had all the hallmarks of being a huge hit. So, when it finally became a major success story for us, nobody was at all surprised. In fact, it was expected.”

10cc were lucky at the time because they had complete control over what they did, and how they did it. In this respect, they reflected the prog ethic of never being tied to a specific formula, and while Gouldman backs away from defining the band as being ‘prog’, he does admit they were a progressively thinking four-piece.

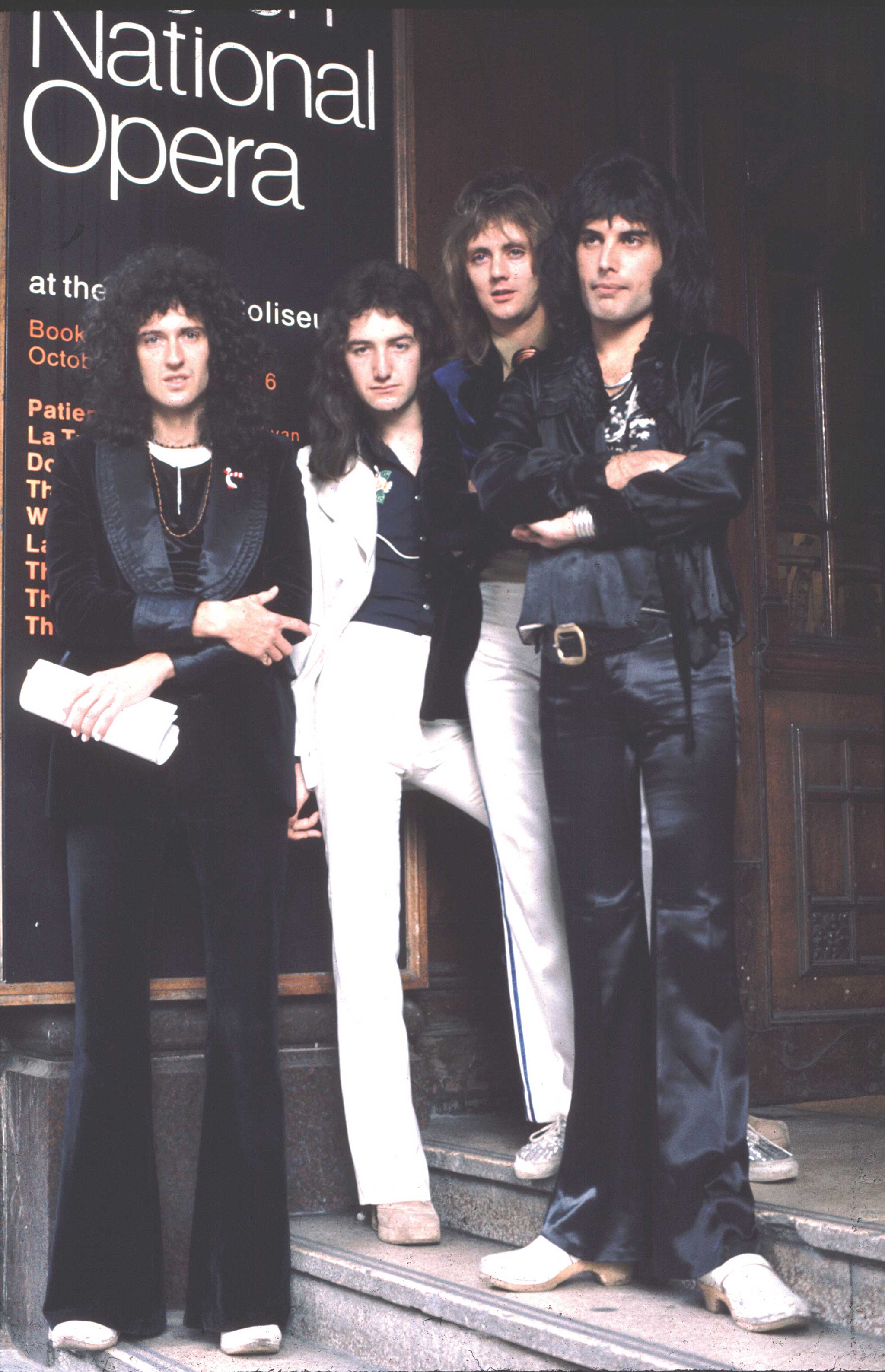

Above, clockwise from back left: Paul Thompson, Eddie Jobson, Phil Manzanera, John Wetton, Bryan Ferry Andy Mackay.

“We refused to allow anyone from Mercury to have access to us while we were recording. We were very much a self-contained unit. The four of us did all the writing, all the singing, played all the instruments, we worked in our own studio and produced everything. And Eric [Stewart] took care of the engineering side of things most of the time. So, we left no room for anyone else to to come in and interfere with what we were doing. It meant we could be as creative and experimental as we wanted, without worrying that business people would insist on a certain approach.”

Gouldman believes that 1975 was a great year for musicians who had a leaning towards the more experimental side of music.

“We had two long tracks on The Original Soundtrack, namely I’m Not In Love and Une Nuit A Paris. Both Kevin [Godley] and Lol [Creme] wanted to have these take up the whole of one side of the album, as they felt they would stand up strongly. But Eric and I were a little concerned this would seem rather pretentious for what we wanted to do. With hindsight, I think Kevin and Lol had a point, but the final decision was down to us four, nobody else.

“Like all of our albums, The Original Soundtrack was unique and different to anything we’d done before. That was part of the challenge we faced with every album: how to make them individual enough to keep us interested as much as anything else. We hated the idea of following a set style.”

Can’s keyboard player Irmin Schmidt agrees that 1975 was a time for healthy musical agitation, and Can made huge strides as they sought fresh avenues of artistic expansion.

“We’d just signed to Virgin at the time,” he recalls. “But while you might think this could have restricted what we could do musically, it did the opposite. Mind you, this was only after a fight with them. They wanted us to get more commercial, which was inevitable, but we were sticking to our guns and being as experimental as we wanted.”

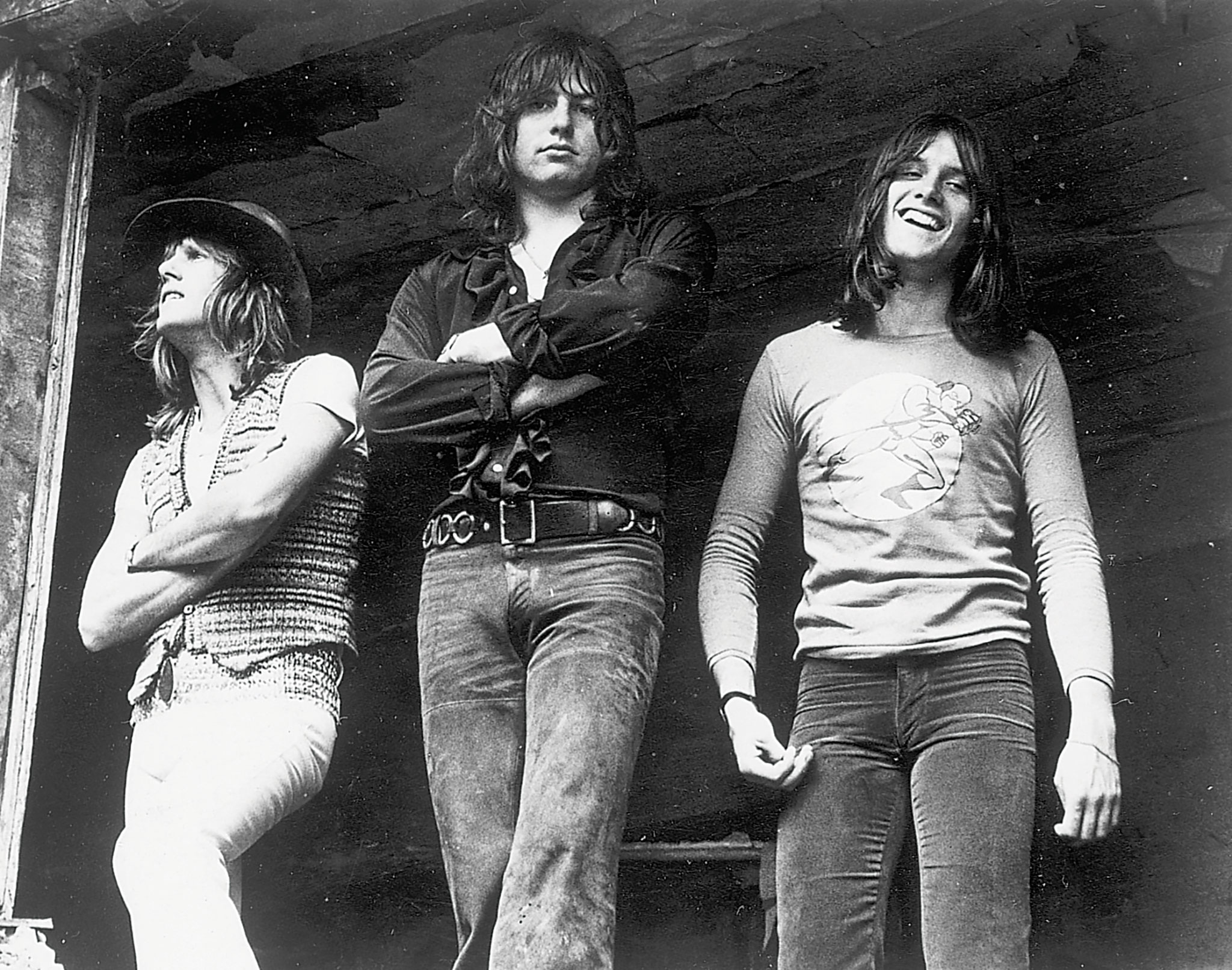

Above, l-r: Eric Stewart, Lol Creme, Graham Gouldman and Kevin Godley of 10cc. Denmark, 1975.

There are those who criticised Can’s 1975 album Landed for being too influenced by the prevailing glam rock scene. But Schmidt claims such opinions as being very wide of the mark. As far as he is concerned, the album betrayed no such impulse.

“For me, anyone who says we suddenly became glam hasn’t listened to the album at all,” he stresses. “I’d admit we sounded a little less aggressive here than we had previously, but that wasn’t because we were chasing what was popular at the time. It was because we wanted to try out different approaches. Maybe it superficially seemed a little more glamorous, but we never wanted it to come out that way. As a band we embraced all opportunities to sound different to everybody else.”

Graham Gouldman remembers 1975 as a time when bands could use modern technology to leave their individual mark.

“This was a time before synthesisers were prevalent. When nobody had heard of sampling. So you were forced to be inventive. That’s what we did on The Original Soundtrack. If we wanted to get a specific sound, then we had to come up with a method of obtaining it, and this could take ages. Now, all you need to do is press a button and you get what you want. But everyone has the same sample programmed in, so they all sound exactly alike. The advantage we had was that because there was no set method of getting anything, we had to literally invent a way of doing it. You could be sure what you got wasn’t repeatable for other bands. It was unique to us, and that gave it an extra value.

“Listen to some of the sounds on The Original Soundtrack, and you won’t hear anything else like these on other albums,” he insists. “Technology had reached a level where things were possible, but it also encouraged you to be creative, because things hadn’t moved on to the point where everything was available. That’s what made it so exciting for musicians like us who loved to challenge themselves, and that’s why bands like us, Queen and Supertramp could all be totally out on our own, while also being part of a broad movement. The bottom line with all of us, though, was that we had a healthy respect for melodies. However clever we might try to be, it was never at the expense of the tune.”

Above: Queen in August 1975.

Across the Atlantic, there was also a caucus of progressively minded bands breaking through, led by pomp rockers Styx and Kansas in the US and Rush in Canada. Each one had their own musical motif, and were also proving that the influence of the original prog giants had taken root and reached far and wide. However, former Kansas guitarist Kerry Livgren doesn’t believe that it was a unified collective. “We didn’t really know any of those other bands,” he says. “We had met some of the guys in Styx, but only early on. So we weren’t on any sort of linked mission musically. Besides, I don’t think there were any bands like Kansas, then.”

John Anthony Helliwell also believes that this new breed were individual and strong enough to stand on their own.

“All of us were bringing different inspirations into the music. From us, you got a mix of big-band jazz, bebop, jazz from the 50s and 60s, surf music, The Beatles. On top of that we all loved Traffic, Spooky Tooth and Procol Harum. I’d say what you were getting from Supertramp was a blend of jazz and classical music, but without being superior. If any band of that time was in danger of being arrogant it was Queen. Don’t get me wrong, I loved what they did, but there were times when they became just a little too overblown.”

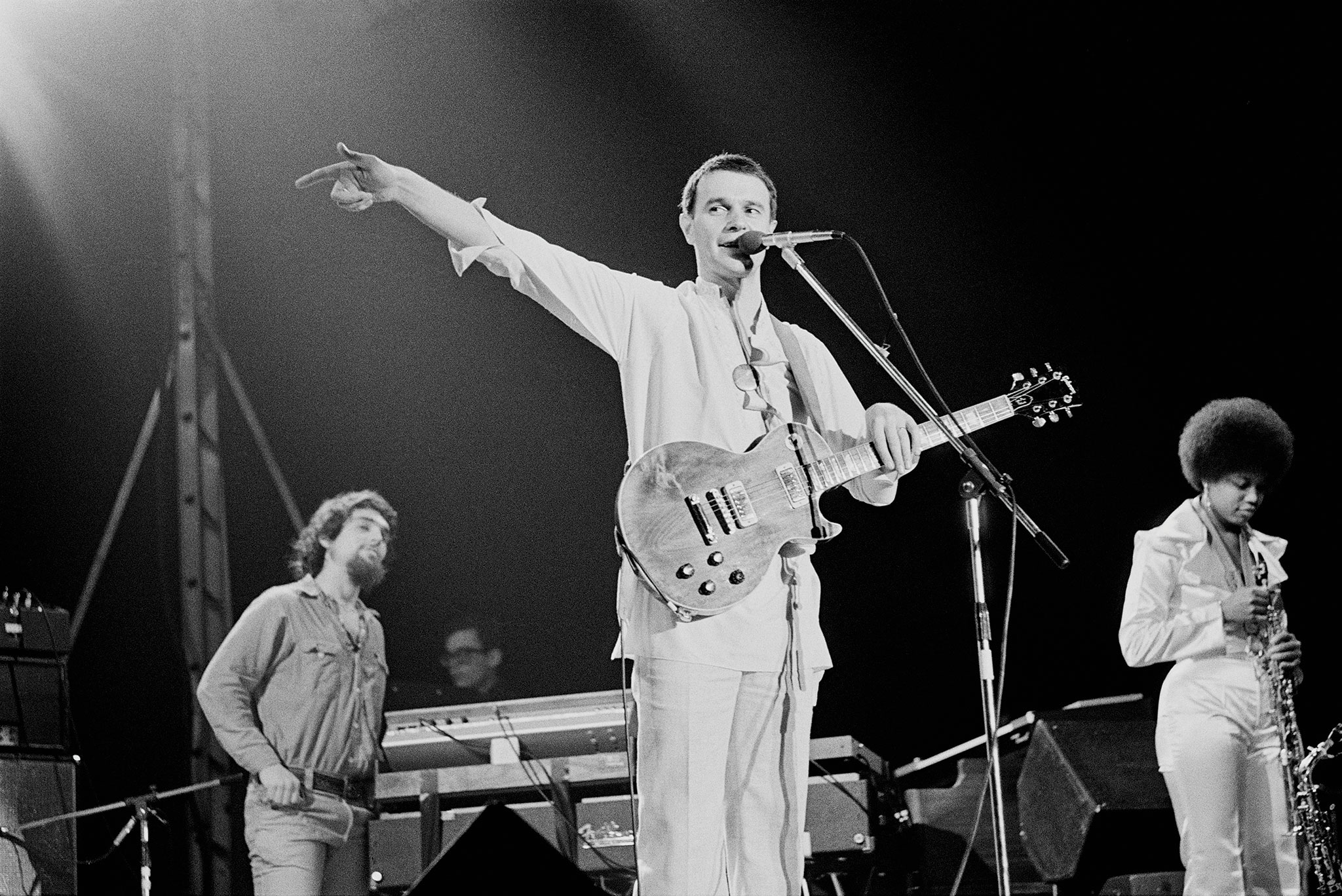

Above: John McLaughlin from the Mahavishnu Orchestra performs live on stage in Hartford, Connecticut in May 1975.

While 1975 saw the rise of a new wave of progressively minded bands, some of the older names were far from finished. The Mahavishnu Orchestra, for one, were definitely trying to adapt their approach to new demands, as guitarist and bandleader John McLaughlin explains.

“By 1975, I had reduced the 11-piece Mahavishnu [the second version] to a quartet,” he says. “I was looking for more essentials and a lighter formation. For the first nine months of that year, Mahavishnu was definitely at a peak, but I could see conflict coming over the horizon.

“This was coming in the form of the group Shakti which I’d formed in 1973. My musical goals at that time were becoming more and more linked to the Shakti form, rather than the Mahavishnu form. That said, the fact that Mahavishnu consisted of drummer Narada Michael Walden, bassist Ralphe Armstrong and pianist Stu Goldberg, was what gave a very creative aspect to the group, especially with Narada. In 1975, he was exploding with creativity, and made a wonderful contribution to Mahavishnu. But by the autumn I’d closed the Mahavishnu chapter and gone to India for several reasons – one as a spiritual journey, and secondly to find a replacement second percussionist to make Shakti a permanent group.”

While some of the older names on the prog scene realised this was a time for change and adaptation, one band decided to return after a three-year lay off in ’75. Van Der Graaf Generator reunited, only to face a very tough period.

Above: Van der Graaf Generator’s Peter Hammill jamming with saxophonist David Jackson, March 25 1975.

“It was a mad year for us,” explains frontman Peter Hammill. “A lot of it was spent on the road, and for the first time in our career we actually played songs live before recording them. When there was a break from the road, we had to go to France to rehearse and then record the Godbluff album. Looking back, we packed all of human life into 1975. The work load was so intense, and we had a lot of bad moments, which included getting our truck stolen in Rome.

“One thing I am glad about was that we were still at the cutting edge of music,” he adds. “A lot of that was because [Van der Graaf Generator keyboard player] Hugh Banton designed and built his own organ, which meant we sounded like nobody else. And because of everything we had thrown at us, we emerged a lot stronger as a band. It brought us together.”

Similarly, Steve Hackett feels that the crisis Genesis faced following Peter Gabriel’s departure actually helped to drive them forward. A lot of the credit for his own more positive outlook was due to the fact that he released his own solo album.

“Doing Voyage Of The Acolyte was very therapeutic, because I knew I could no longer rely on Genesis and had to become more self-reliant. The [Top 30] success of Voyage… helped me to think a lot more clearly. It gave me the confidence in my ability that I lacked previously. I could no longer be the guy in the corner strumming guitar and hiding in the shadows. I had to come out of my shell, and when I did I knew Genesis could move forward without Peter.”

Above: Supertramp, l-r: Rick Davies, Dougie Thomson, John Helliwell, Roger Hodgson and Bob Siebenberg.

“We got the songs together for what became A Trick Of The Tail in the summer of ’75. And we were all united by then on moving onward. For me, this was the year when the band blossomed, because we had no choice.”

With hindsight one can see the way in which the prog world was evolving and changing – as it had to or face death through stagnation – but few of the musicians vital to the scene could actually see this happening.

“We were too involved in getting together what we were doing to worry about other bands and their situations,” says Irmin Schmidt. “Obviously we came across them sometimes. But it never bothered us what they were doing. The only people we were in competition with was ourselves.”

Peter Hammill also admits to being cocooned from the outside world.

“We had such a tiring and constant schedule that we hardly had the time to look up and see what anyone else was releasing. But I’m glad we were so cut off, because it meant our creativity wasn’t diluted by other influences.”

This sense of being musical hermits also spread beyond what was going on in progressive music. John Anthony Helliwell admits that Supertramp were unfazed by global events.

“It may seem strange to anyone not in a band, but even though we toured a lot in America at the time, and also lived around the Venice Beach area of California, we didn’t write any songs about our environment or major happenings for [September 1975 album] Crisis? What Crisis?. In fact, the title of the album itself was our way of expressing the way we’d been cut off from the news.”

Above: Party on: Eric Stewart (left) and Lol Creme of 10cc hold promotional balloons in New York, October 1975.

“All we did during this period was play live, write and record,” agrees Graham Gouldman. “We never even hung out with other bands in social situations. And we never thought of bands like Roxy and Queen as rivals. Maybe it was because we were virtually living in each other’s pockets that we couldn’t see the cracks beginning to appear between Kevin and Lol on one side and Eric and I on the other. This wasn’t an issue until 1976, but if we could have been a little more open the previous year, the split [when Godley and Creme left the band] might have been avoided.”

“For me, bands like Yes and ELP went too far,” attests Helliwell. “What they were doing was becoming clever for its own sake. That was counter-productive. I would never argue about the validity of what these bands had done earlier in the decade, but there was a need for us, 10cc, Roxy Music and others. The giants of prog had alienated the next generation of fans who found their approach off-putting. They warmed to us because our music was welcoming.”

Perhaps John McLoughlin best sums up the prevailing mood at the time:

“For me, 1975 was a year of division. Not only in musical but sociological terms. Bands such as Supertramp and Roxy Music were in the ascendant, although personally, I would have put Yes with these artists, rather than opposed to them. In a way Roxy and 10cc had an element of ‘glamour’ about them, which was something new for prog. Don’t misunderstand me, I always liked Supertramp, Yes and bands like that, but they weren’t at all part of a radical movement, either socially or musically. It was evolution that was happening, not a revolution.”