"Mike Bloomfield came up to me at the Avalon Ballroom and says, ‘You can’t do that’. I said, ‘C’mon, Mike, you can do it, too. All you gotta do is turn this knob up to 10'": The story of Blue Cheer, the band who invented heavy metal

LSD, rehab, whiskey, fights, and in their spare time Blue Cheer invented heavy metal. This is their twisted tale

Blue Cheer might have been named after a particular batch of LSD produced by Haight Ashbury acid guru Owsley Stanley, but they were unlike any other San Francisco band to emerge in the 60s. They were the sound of the Jimi Hendrix Experience filtered into an elongated, deafening, primitive howl; they were Motörhead 10 years before Motörhead. And in 2009 the band told Classic Rock their story.

They were the bellowing Gods Of Fuck. There were no big ugly noises in rock’n’roll before Blue Cheer. They created sonic brutality, coiling their teenage angst into an angry fist of sludge and feedback and hurling it at stunned, stoned hippies like a wave of mutilation. Everything about them was badass. They had a Hell’s Angel for a manager, they were despised by the other bands in their scene, and they played so loud that people ran from them in fear. Proto-punk, proto-metal and proto-rehab, Blue Cheer took acid, wore tight pants, cranked their walls of Marshall stacks and proved, once and for all, that when it came to all things rock, excess was always best.

Formed by singer/bass player/mad visionary Dickie Peterson in San Francisco in 1966, Blue Cheer – named after the band’s favourite brand of LSD – was at first a gangly, six-piece blues revue with much teenage enthusiasm and little direction. After seeing Jimi Hendrix perform for the first time, the band’s prime movers – Peterson, drummer Paul Whaley and guitarist Leigh Stephens – thinned the line-up and discovered their sound, a wall-shaking throb of low- end beastliness that sounded exactly like the world ending.

Anchored by a sweat-soaked, hell-for-leather cover of Eddie Cochran’s teenage lament Summertime Blues, Blue Cheer’s definitive sonic manifesto Vincebus Eruptum arrived in 1968. It was the blues defined by acid-fried biker goons, and it changed the world. Two years later, the band was effectively over, its members shell-shocked, disillusioned, ripped-off and super-freaked. And it would take 40 years for them to put all the pieces back together.

Blue Cheer’s original and present drummer, Paul Whaley, speaks in a ragged whisper that suggests life done the hard way. Much like his perpetual partner- in-crime, band leader Dickie Peterson, Paul now lives in Germany, far from the psychedelic madness of the US west coast that spawned them.

“He met a girl, I met a girl,” he explains, simply. “I’m much happier here. That American style of life, it just makes me nervous.” Between long and thoughtful pauses, Paul recalls how the Blue Cheer story began.

“Dickie and his brother showed up in Davis, California, in 1966,” he says. “They just showed upon the streets of this small town, these two trolls. These two long-haired freaks.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Paul and Dickie became acquainted, and when Dickie moved to San Francisco to soak up the free-love-and-cheap-drugs atmosphere and form a band, he gave Paul a call. “I was doing nothing at the time, so I agreed, and I moved down there to this commune he was living in. I joined the band he was in and it eventually became Blue Cheer.

It was a 60s blues band. We went to the Monterey Pop Festival and saw Hendrix there, and decided we wanted to be a three-piece. It all happened really fast. Within six months we were signed to Mercury Records and playing loud, aggressive music. The three of us got together and wrote Doctor Please and Auto Focus for the first album, and it sold millions. That Vincebus Eruptum album has brought us to this point.”

As with any revolutionary concept, Blue Cheer had its detractors. Summertime Blues climbed the charts, and Blue Cheer were the toast of the town. Unless, of course, you asked the bands they actually had to play with.

“People thought we were just making noise,” says Dickie Peterson, from his home in Germany. “They thought we were a detriment to the scene. I just knew we wanted to be loud. I wanted our music to be physical. I wanted it to be more than just an audio experience. This is what we set out to try and do. We ended up being in a lot of trouble with other musicians of the time.

"I remember Mike Bloomfield came up to me at the Avalon Ballroom, and he says, ‘You can’t do that’. I said, ‘C’mon, Mike, you can do it, too. All you gotta do is turn this knob up to 10’. He hated me ever since. He was this great accomplished musician and I was this 18-year-old smartass,” Dickie laughs. “We did have a bit of an arrogance, but it was nurtured by people like that criticising us.”

Despite being heavier and louder and more stoned than everyone else, Blue Cheer had a song in the charts, and so they were forced to make the rounds on Top 40 radio shows and prime-time television programs just like any other band. It was not always a perfect fit.

“We were on American Bandstand,” Dickie remembers, “And Dick Clark [AB’s host] didn’t like us at all. My manager was a Hell’s Angel, and we were sitting there smoking a hash pipe, and Dick Clark comes in and says, ‘It’s people like you that give rock’n’roll a bad name’. We looked at him and smiled, and said, ‘Thanks a lot, Dick’. We did the Steve Allen show too, and that was a real kick in the ass. When they introduced us, Steve Allen said, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, Blue Cheer. Run for your life’.”

Media relations was just one of the hard lessons the young band had to learn.

“We were basically street kids,” Dickie explains. “We were never around the kind of money we were getting. There was a lot of financial mismanagement. All the songs I wrote, I lost my publishing for all of those. I didn’t know it when it happened. There was a lot of business – not just with us but with a lot of bands in the 60s – that was just slipshod.”

1968 was still in full-swing when Blue Cheer were marched back into the studio for their second album, and already there were signs of wear and tear in the band. Guitarist Leigh Stephens had quit, fearing deafness if he continued to play with the louder-than-God band. He was replaced by Randy Holden. Vincebus Eruptum was recorded in three days, with very little mixing. For their follow-up, the label demanded some actual production. This proved difficult.

“We had never done a studio production,” Dickie explains. “It was all new to us. We couldn’t turn our amps up the way we wanted to and get the tones we wanted. So the record company rented a pier in New York Harbour, and so we went out there with a mobile unit and recorded all the basic tracks. And then we went back into the Record Factory and did all the sweetening – which was a lot.”

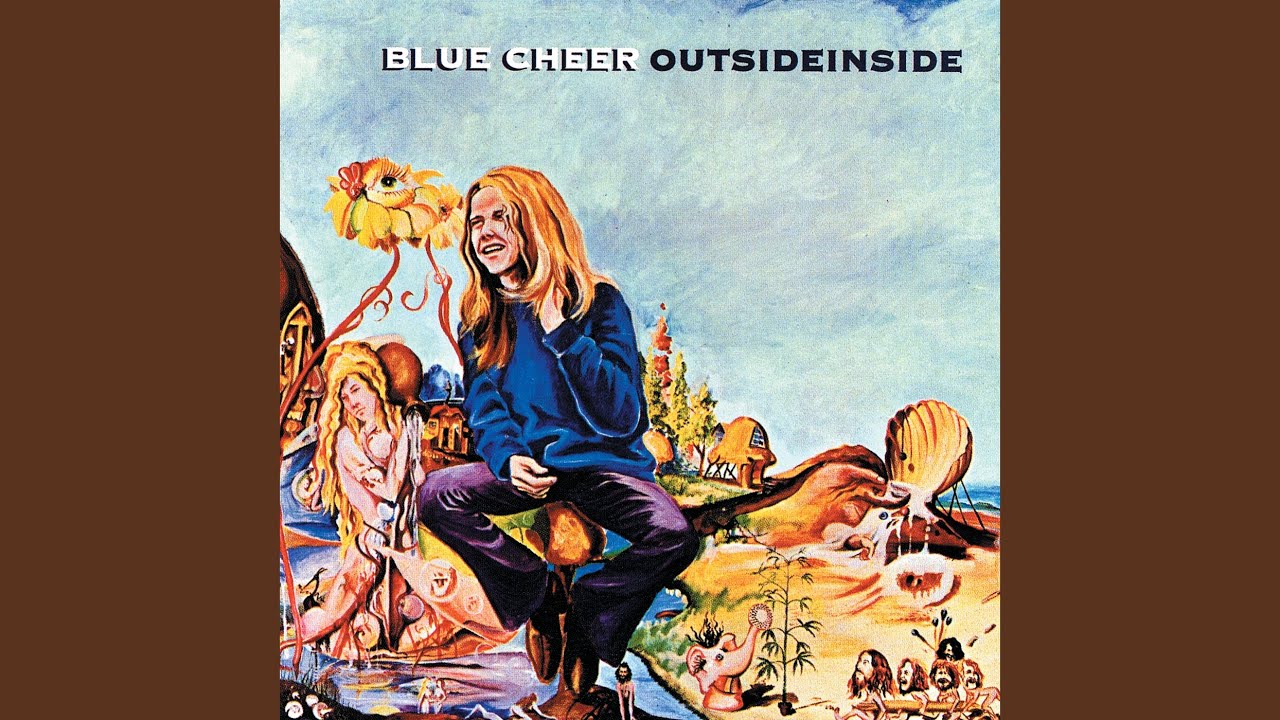

The result was 1968’s blistering Outsideinside, perhaps the only album in existence recorded outside, in New York Harbour, because the band were too loud to play in a studio. “We knew we were doing something that no one had done before,” Dickie says. “We thought it was so absurd, we just had to do it.

Despite being nearly as loud and twice as fuzzy as its predecessor, Outsideinside failed to do the brisk business Vincebus… did. While the band continued full-bore, the atmosphere in San Francisco and in the band were both radically changing.

“You know, there were some sides of the 60s that were absolutely amazing,” Dickie says. “You could go down to Haight Street, and if you were hungry and didn’t have any money you’d be fed. If you were out of money and you had your wits about you, you’d find a place to sleep that night. It wasn’t until hard drugs walked in, around 1969-70, that it started going sour. We were using by then. I don’t hide the fact that I was a heroin addict for 15 years. I’ve been away from that since the late 70s, but that’s when things all went to shit.

There was a lot of desertion from the revolution. There were a lot of people that went back to college or went back to their parents’ real estate agency or selling life insurance, on and on. I see ’em all the time. In one respect, I understand it. Maybe if I’d been educated, I would’ve too, but I’ve never done anything but play music. So I never had anywhere to go to. But another side of me says that it’s desertion in the face of the enemy.”

Paul Whaley quit the band in 1970. “We started screwing around with drugs,” he says. “And the wrong kind of drugs, too. The money was going, there was conflict between me, Dickie, and our guitar player at the time, Randy Holden. The chemistry just wasn’t right. There were arguments, and we just didn’t want to be around each other. So we just decided to break it up.”

Soon after leaving the fold, Whaley was invited to join Brit folk-psych band Quiver. Unfortunately drugs hobbled any chance of the situation working, and Whaley soon after dropped out of the music scene completely. He spent the next decade lost in an endless loop of dope and rehab. Peterson struggled as well, not just with drugs, but with a seven-album record contract that still needed to be fulfilled, despite the fact that his band had already broken up.

“The band sorta dissolved, and I got stuck trying to pull musicians together to try and get stuff done,” Dickie says. “That’s why out of those first six albums, four of them are much different. I don’t think the music is bad, it’s just different.”

Dickie and a motley crew of friends, hangers-on, and studio musicians eventually recorded and released four more ‘Blue Cheer’ albums from 1969 to 1971. They are clearly rushed affairs, jammed with forays into country rock, organ-dominated prog and breezy West Coast jangle. Although each album contains a gem or two, these albums are clearly not the work of the young savages who played so loud they had to record outside. Those mad bastards were already long gone. When the whole trying process was over, Dickie Peterson, addicted, drained and heartbroken, chopped off his freak-flowing mane and vanished.

“I retreated for a while,” he acknowledges. “Like I said, I was addicted. In 1973, I went into rehab, and I stuck with it for four years. At the time, I wasn’t even sure I still wanted to be a musician. When I was finished with that, I was sort of incognito. I would go into places and hear bands cover my songs. I would never identify myself, though. I was in Northern California, just being anonymous.

"Then, around the late 70s, I ran into a friend who knew where Paul was. I called up Paul, who was living in England. I asked him if he was interested in talking about putting the old band back together. He said he was, so I flew over and we talked about it. Two weeks later, we were back together in the states, hashing it out.”

“It was out of the blue,” Paul remembers. “At the time, we had no contact with each other whatsoever.”

“We were just trying to get it together,” Dickie says. “We had gained nothing from our earlier successes. It was like trying to start all over again.”

Andy ‘Duck’ McDonald grew up in Almeida, New York, the same heavy metal hotspot that spawned Ronnie James Dio and Manowar. He’s played in many bands over the decades, from Shakin’ Street to Savoy Brown, but for the past 20 years, he’s been the new guy in Blue Cheer. Besides swinging Cheer’s mighty axe, he also serves as their business manager and, when it’s called for, their historian.

“I met Dickie through Carl Canedy,” Duck remembers. Canedy, the drummer/producer/visionary behind New York raunch n’ roll institution The Rods, served as producer on Blue Cheer’s first ‘comeback’ album, 1984’s The Beast Is Back. McDonald was also in the same Rochester studio working on Canedy’s star-spackled solo album, Thrasher Supersessions.

“So, we were both in the studio at the same time,” Duck explains.

“I was a drinker at the time, and so was Dickie. I had a bottle of Jack Daniel’s in the studio, and I made the mistake of leaving it there. Dickie happened to find it. We’re talking 10 in the morning here. So I walk in the studio about noon, ready to work, and Dickie’s in there, and my bottle’s half gone. I go, ‘What are you doing? That’s my whisky!’ But he was so cool and so innocent about it that I said ‘Fuck it’, and we just finished the rest of the bottle together.”

Dickie doesn’t remember the meeting in such friendly terms.

“We got in a fight over whisky,” he says. “So I went and bought another bottle, because he’s much bigger than me. I mean, I’m no idiot.”

“I really liked his attitude,” Duck says. “He wasn’t a jerk or a rock star. We went our separate ways after that. They went on tour and did The Beast Is Back record, and I did my own thing. It was a few years before I heard from him again.”

Released on New York’s Megaforce Records, one-time home to thrash metal juggernauts like Metallica and Anthrax, 1984’s The Beast Is Back was to be Blue Cheer’s comeback record. It was their first album in more than a dozen years, and arrived near the peak of heavy metal’s stranglehold on American pop culture. The only problem was, Blue Cheer may have spawned the whole genre, but they weren’t a heavy metal band.

“I wasn’t too surprised that they ended up on Megaforce,” Duck says, “Because there was a resurgence at that time. Heavy metal was huge, so it was a good time to bring back Blue Cheer. Of course, the guy they had then, Tony Rainier, was a heavy metal guitar player. It’s just what you had to play at that time. As well as, you know, the puffed-up hair and tight pants. Dickie even had a perm at that point.”

“Tony, who was our guitar player in the early 80s, this was his concept,” Dickie says. “I was pretty much against it. Not because I think heavy metal is a bad thing, because I don’t, it’s just not us. We’re a heavy, low-end, hardcore rock’n’roll band.”

Mottled with bad ideas – including a screech-metal remake of Summertime Blues – the noodling The Beast Is Back was greeted by fans as a curiosity, at best. Still, the band was together again, tenuously or not, and Dickie wanted to make the best of it. Blue Cheer spent the next few years slogging it out in the heavy metal trenches, waiting for the spandex kids to come around to their way of thinking.

“In 1989, Dickie wanted to go to Germany,” says Paul Whaley, “and Tony didn’t want to fly. He was afraid Blue Cheer would jinx him, and the plane would crash. So Dickie gave Duck a call, and he went to Germany with Dickie and another drummer. I didn’t want to go to Germany, either. I thought there was a jinx against Blue Cheer at the time, as well.”

Duck agreed to do the tour, and the band recorded a live album, 1989’s Blitzkrieg Over Nuremberg, just two nights in. Although this line-up was short-lived, Duck would return to the fold again and again over the next few years. Paul Whaley finally got over his fear of flying and joined Dickie in Germany, where they would eventually put down roots. Meanwhile, back home, a certain kind of metal died an embarrassing death at the hands of Seattle’s flannel mafia. Time for the Cheer’s second comeback.

“Here was an opportunity, “ says Duck, “With all these grunge bands. Blue Cheer had a heavy influence on a lot of those bands.”

“They liked us because we didn’t write songs about devil worship,” Dickie says. “We wrote songs about drugs and sex, just like them.”

Clearly, Blue Cheer’s downer-fuzz and proto-punk holler were pronounced influences on bands like Green River, Soundgarden and Nirvana, so it seemed like the perfect fit. In 1990, the band recorded a new album, Highlights And Lowlives, with grunge superproducer Jack Endino. Despite its grunge-ready, doom-washed excess, the album fizzled, as did grunge.

The band retreated to Germany, where they tinkered and retooled. Unhappy with the German management, Duck quit, and was replaced with a German flash metal guitarist Deiter Saller. The resulting album, 1992’s Dining With The Sharks, was another misfiring foray into metal. “I was very displeased with the record company, with the production, with the whole thing,” Dickie remembers. “All I wanted to do was it get it done and get out.”

The Blue Cheer story effectively goes dark for the rest of the 1990s. At the tail end of the decade, Duck McDonald returned to the fold for a successful – if slightly Spinal Tap-esque – tour of Japan. Over the next few years, the trio of Peterson, Whaley and McDonald solidified into perhaps the most stable and creative line-up so far for the constantly embattled band. The next step was to write and record that next great album, the one that could stand up beside Vincebus Eruptum as a definitive document of Blue Cheer’s mastery of fuzz and volume. It took them nearly a decade, but eventually, they did.

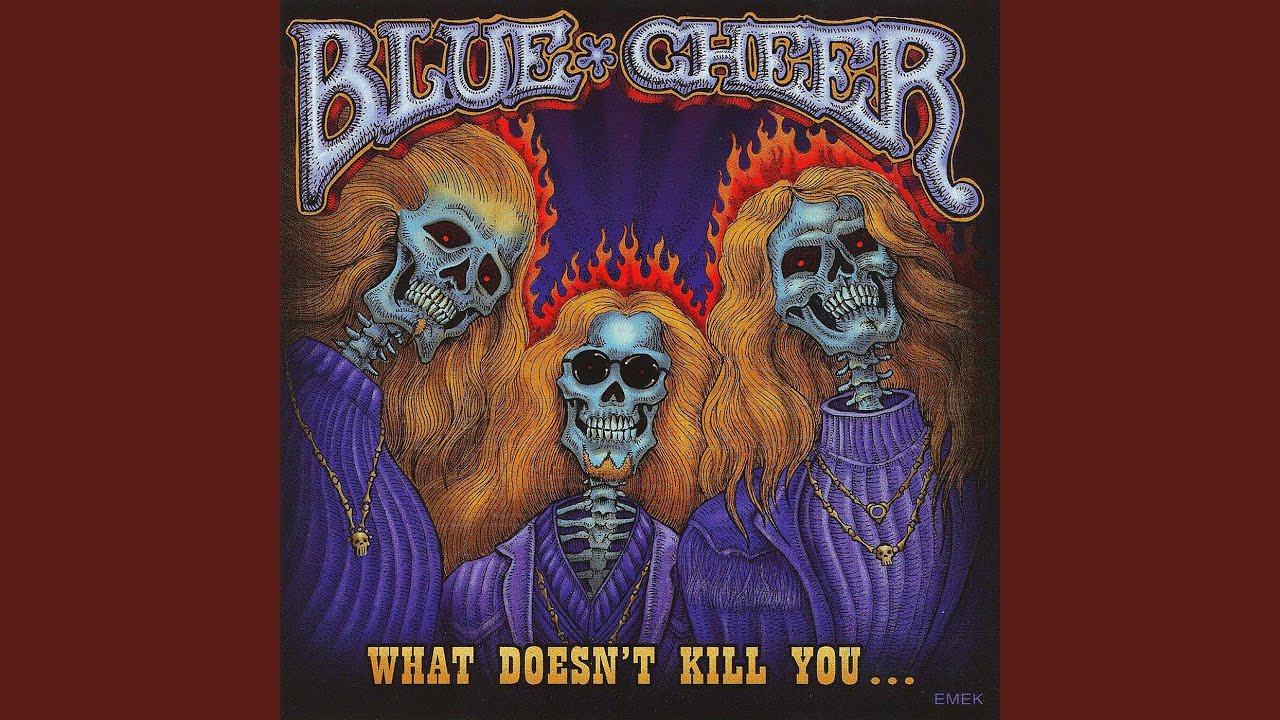

In 2007, Blue Cheer released the overwhelming What Doesn’t Kill You, a 12-ton punch to the snot-locker that sounded less like a creaky 60s band reliving fuzzy, ancient memories than a vital new force of dope-rock motorcycle crazies on a village-pillaging rampage. Ear-searing scuzz-rockers like I Don’t Know About You and Rollin’ Dem Bones combine jungle-beat primacy with stoner-rock crunch and Blue Cheer’s patented low-end elephant stomp in an orgy of manlyswagger and pill-shovel excess. It is clearly their best record since 1968’s Outsideinside, and that is entirely the point.

“It was an attempt to combine everything we’ve been,” says Dickie. “And bring it up to date.”

Duck elaborates: “I said to Dickie, for this album, we have to go full circle. We have to tie the first two albums with this new album, and everything in between, well, that just kinda disappears. We had to tie up the beginning and the end. I say that because I don’t know how many Blue Cheer records Dickie’s got in him. Maybe another one, I don’t know. This could be Blue Cheer’s last record, and that’s the way we looked at it.”

Despite the new album’s virility, it did not make the back-in-black splash the band had hoped. Surely it will gestate, and five decades from now, way-out teenage freaks will form biker gangs and sex cults based on its teachings. That, however, does not help the band now. Fortunately for them, the albums have always been incidental. The real proof of their menace and might occurs onstage.

“I think when we play them live, it’s a better representation of the songs than what’s on the album,” says Paul Whaley.

“When we play them live, people go fuckin’ crazy. We’ve done tours with a lot of heavy young bands in the past few years, and we stand right up next to ’em, if not surpass them. Blue Cheer is a really heavy band, man,” he says, with obvious pride. “It’s a great feeling to play so aggressive and loud again.”

Paul and Dickie both live in Germany full time now. Duck lives in upstate New York. You’d think that would make playing live difficult, but it is evidently a trifling matter to these everlasting behemoths.

“It’s not as difficult as it seems,” Dickie says. “We just have to figure out where we’re supposed to be, oil the gears, and hit it.”

“What we do is we headline small clubs and we get all these great new bands to open for us,” Duck explains. “Mostly from the stoner rock scene. Bands like Dead Meadow, Buffalo Killers and The Suplecs. We love these bands because they’re heavy and cool, and they like us because we’re not assholes or rock stars. It’s wonderful to be able to tour in that atmosphere. I mean, we’re 60-year-old men moving our own equipment, touring in a van, just like these kids are. They see us doing it and they can’t believe it. We’re back in the garage,” he says, “And that’s where we like it. That’s where we belong.”

As Blue Cheer vault past their 40th year in rock’n’roll, it is easy to see why they’ve endured, despite all the dirty deals, lost decades and bitter disappointments. They are part of a very exclusive cabal of 60s and 70s cult rockers who never, ever lost their street cred – streetwalkin’ cheetahs and lightning smokers who maintained their aura of teenage cool even as they enter their sixth decade and beyond.

Bands like The Sonics, The Stooges, the MC5, Steppenwolf, Hawkwind, the New York Dolls, and Blue Cheer will never find themselves on the bottom-rung of some creaky oldies revival show. They all remain vital conduits to rock’s primal source and still attract as many with- it kids as they do greying, freak-flag holdouts. It’s 40 years later, and Blue Cheer still know how to kick out the jams, motherfucker.

“If we were ever considered nostalgic, we’d quit,” says Dickie. “I really mean that. Because that would mean we could no longer do what we do. See, it’s not like fathers and sons at the shows, it’s grandfathers and grandsons that are coming to see Blue Cheer. It’s unbelievable. We’re living testimony that it’s not over after 30.”

Certainly, the touring may have slowed, and it’s entirely possible that What Doesn’t Kill You will remain Blue Cheer’s final album. But the story is far from over. The band is still playing European festivals and taking on shorter US club tours. There’s a live DVD in the works, and Dickie Peterson is hard at work on his first solo album. The odds are, Blue Cheer will be bringing their devastating low-end to some town near you soon. And you probably won’t even believe it.

“Half the time, when people see a Blue Cheer show advertised, they don’t believe it,” says Duck. “They think it’s got to be some kind of Blue Cheer cover band. They just don’t really don’t believe it’s possible.” Duck laughs. “People just figure, ‘Those guys can’t possibly still be alive.’”

Dickie’s been hearing rumours of his demise for years now, and so far, they’ve all been false. “Not only am I not dead,” Dickie chuckles, “I remember every second of the 60s. LSD does that for you.”

The feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 134, Summer 2009. Dickie Peterson died later that year, and Paul Whaley in 2019.

Classic Rock contributor since 2003. Twenty Five years in music industry (40 if you count teenage xerox fanzines). Bylines for Metal Hammer, Decibel. AOR, Hitlist, Carbon 14, The Noise, Boston Phoenix, and spurious publications of increasing obscurity. Award-winning television producer, radio host, and podcaster. Voted “Best Rock Critic” in Boston twice. Last time was 2002, but still. Has been in over four music videos. True story.