Gil Bridges truly is the last of the last of the last. He has endured the deaths of three of his bandmates, the permanent retirement of another two, and the betrayal of yet another. He has experienced racial segregation, record label meddling and indifference, protracted lawsuits, and even the slow and inexorable decline of his band Rare Earth’s once-bustling home town of Detroit.

He has endured because the music has endured. Rare Earth’s twin monster jams, I Just Want to Celebrate and Get Ready, still get people on their feet nearly four decades later. Both songs are laced with a sort of crazy magic; a rock’n’roll mojo that has never ceased to enthrall, intoxicate and elevate. When you hear them you will feel good – guaranteed.

Rare Earth’s music straddles genres and defies categorisation, slipping seamlessly between the two seemingly disparate worlds of classic rock and R&B. This careful balancing act is a rarity even now, and was a near impossibility in the colour-segregated 60s when Rare Earth began their journey. Groundbreakers and pioneers, this post-racial band should have been the first of many. Instead they remained one of a kind.

It seems oddly antiquated to use bluntly divisive terms like ‘too white’ or ‘too black’ to describe a band’s music, but Rare Earth’s early career was often dominated by such unfortunate race-specific labels.

“When we first started playing, Motown Records [whose roster was almost exclusively black] had the radio locked up, especially here in Detroit,” says Bridges. “That’s what we were listening to when we started out, that was our roots. That’s where the R&B came from. People were astounded that a white group could play black music, but that’s where we learned. That’s what we loved, listened to and played. Later on we had to deal with that kind of stuff – “You guys sound too white on this record” – but we never even thought of that back then. We just loved the music.”

In the beginning they were The Sunliners, a teenage garage band. And, frankly, they were kind of square. They formed in 1960 and gigged around Detroit for eight years; they were local heroes, but had yet to make an impact outside the city. Then, in 1968, the ‘dawning of the age of Aquarius’ hit. And The Sunliners decided it was time for a change.

“There was a radical shift in the music,” Bridges remembers. “Bands had these crazy names like Iron Butterfly all of a sudden. ‘The Sunliners’ just wasn’t making it any more.”

They changed their name, choosing Rare Earth because it sounded significantly ‘with it’. The change worked, and the band were soon signed to Verve Records who released their debut album, Dreams/Answers, in 1968. The album flopped, but Rare Earth’s reputation as one Detroit’s preeminent live bands continued to grow.

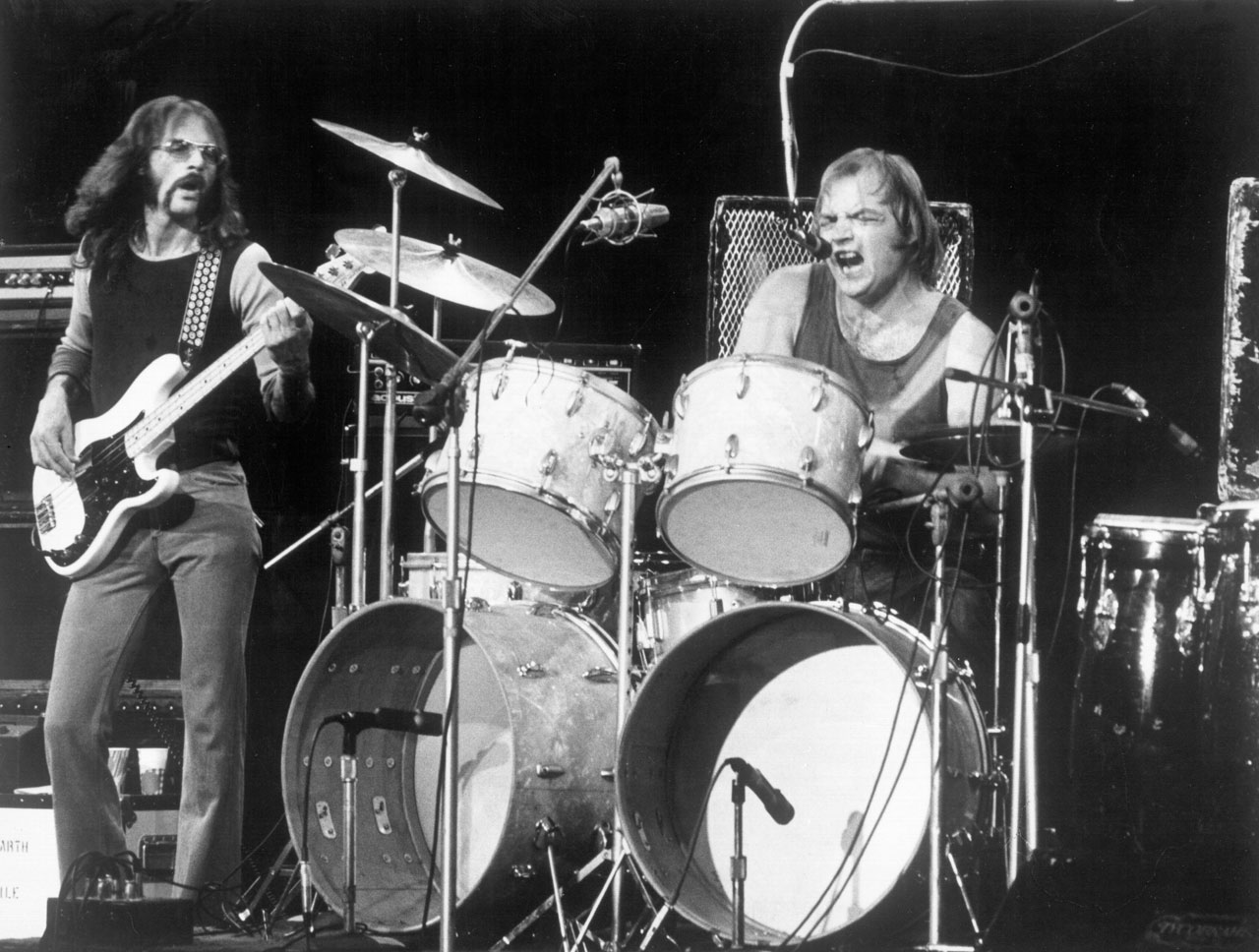

“We always played headlining shows back then,” Bridges says. “Bands like Steely Dan and the Doobie Brothers would open for us. We did a lot of shows with Funkadelic, too. We’d get a real charge out of playing with them. They’d do stuff like perform in diapers. The level of performance back then was astounding, so we always had to be on our toes.”

Rare Earth had a knack for improvisation, and could jam on a song for, literally, hours.

“We hardly ever recorded anything under seven minutes long,” Bridges laughs. “We were a jam band, a street band. Some of the songs on our albums are absolute jams, we created them in the studio on the fly. We took the same approach when we played live.”

Rare Earth soon caught the ear of Berry Gordy, the founder of Motown Records.

“There were other white bands that signed to Motown prior to us,” says Bridges, “but they didn’t go anywhere because Motown had no promotion in the white market. That’s why when they approached us they told us they were starting a whole new division, one that catered exclusively to white acts. They were also planning on bringing on some British bands as well. They didn’t have a name for this new division yet. Jokingly I said: ‘How about Rare Earth?’ And they said okay. That’s when we signed, because we knew they’d be behind us 100 per cent.”

The band got to work on their first album for Motown at the legendary Hitsville USA studios. The result was 1969’s Get Ready, a masterpiece of gritty, bluesy dance music that included covers of Traffic’s Feelin’ Alright and the Nashville Teens’ stomper Tobacco Road, and was anchored by the ecstatic title-track, a 21-minute, ode-to-joy jam on Smokey Robinson’s Motown classic that took up the whole of side two.

“We used to do Get Ready as the finale in our live sets,” says Bridges. “So it already was 21 minutes long. And we figured that since [Iron Butterfly’s] Inna Gadda Da Vida took up one whole side of an album, why couldn’t we? Motown freaked when we told them our plans. It was very much against their nature, but they let us do it. And it worked out great.”

Initially, much like the band’s first album, Get Ready stalled at the gate. “The record didn’t do anything for the first six months, and we thought, ‘Uh-oh, we’ve got a dud on our hands.’ And then all of a sudden a black DJ in Washington DC spun the record. At that time, ‘album-oriented radio’ was just coming out; it wasn’t just three-minute singles any more, the DJs could play longer songs and they had the choice of what they wanted to play.

"The DJs really liked our song because they could take a coffee break or go to the bathroom or whatever, because they had 20 minutes on their hands. People went wild for it in Washington and it just spread out from there. The record broke in the black market first, and the first concerts we played were to black crowds; they were all shocked and surprised when a bunch of white guys got on stage.”

Eventually Get Ready caught on with white audiences as well, and the band struggled to keep their sound as open-ended as possible. Not an easy task when you’re signed to Motown.

“Motown always had writers and producers that they wanted you to work with,” Bridges explains. “At one point they set us up with Stevie Wonder as a producer. He was 17 at the time, and they wanted to try him out. He really wanted to produce us, and it was his first attempt. The problem was that our singer at the time, Pete Rivera, could emulate anybody, and Stevie was making him sound just like him. I didn’t think that was good. Neither did Motown, so they shelved the project.”

The band settled in with producer Norman Whitfield, a pioneer of ‘psychedelic soul’, and together they scored another US hit in 1970 with (I Know I’m) Losing You, which had already been a hit for Motown royalty the Temptations. But Rare Earth’s most enduring triumph occurred a year later – although it almost didn’t happen at all.

“I Just Want To Celebrate was written by these two Greek white writers, Dino Fekaris and Nick Zesses, who worked for Motown,” Bridges explains. “They had staff writers and writing rooms, with a piano in each room, and these guys were going all day long, every day. They were writing material for all of Motown’s acts. And we happened to walk into the studio one night and they played …Celebrate for us. We were there to record something else, but we scrapped it right there and did …Celebrate instead. We recorded the whole song, vocals and everything, in one day.”

Perhaps the ultimate party anthem, I Just Want To Celebrate encapsulated everything that was great about Rare Earth. It had groove, energy, a wicked hook, and it lasted for days. It remains a near-constant presence in television, films, and parties the world over. It was also the high-water mark for a band that had achieved little real fame; they had, however gained some notoriety for being put down in the lyrics to Gil ScottHeron’s poem The Revolution Will Not Be Televised, which included the line: ‘The theme song [to the revolution] will not be written by Jim Webb, Francis Scott Key, nor sung by Glen Campbell, Tom Jones, Johnny Cash, Engelbert Humperdinck or the Rare Earth…’

They scored another hit with punk/funk classic Hey Big Brother a year later, but as the 1970s wore on the band began their slow downward spiral. Willie Remembers, in 1972, was the first Rare Earth album written and produced solely by the band. Motown thought it was ‘too white’ and refused to promote it. The follow-up, 1973’s infamous Ma, was written and again produced by Norman Whitfield. Motown also had problems with that album, and were prepared to allow it to wither and die.

The band continued to record and tour, but a follow-up worthy of I Just Want To Celebrate never materialised. In 1974 vocalist Pete Rivera left the band, having had major personal and business disagreements with their manager, Ron Strasner, and seen the other band members join Strasner’s corner. Rare Earth never fully recovered from the split, and despite a short-lived re-formation in the early 80s, Bridges and Rivera were never able to resolve their differences.

“Peter Rivera is the reason Rare Earth isn’t together today,” says Bridges, matter-of-factly. “After the break up in ’75 we went to court over the name. I won the name and he was out. He wanted to fire everybody, including me. He had Lead Singer Syndrome.”

- Cult Heroes: Starz - The Band Who Grabbed Defeat From The Jaws Of Victory

- Cult Heroes: Blue Cheer - the band who invented heavy metal

- Cult Heroes: The Godz - the crazed story of America's great lost biker band

- Cult Heroes: Man - the Welsh jam band who won't stop playing

Rivera – who declined to be interviewed for this story – went on to join the Classic Rock AllStars, a touring ‘supergroup’ that also features members of Sugarloaf and Iron Butterfly. As the decades wore on, Rare Earth lost members to death and career changes, but Bridges soldiered on. Although the band spent a good portion of the 70s in Los Angeles, he also moved the band back to its roots in Detroit, where he remains to this day.

“It’s a much different place now,” he says of the then-legendary Motor City. “It’s really tough here now, because so many people have lost their jobs. Once the car companies closed down, things really went downhill. It was a booming city when we were coming up, though. You should have seen it. The car industry was going full steam ahead, Motown was happening, everybody had jobs. It was good times.”

Rare Earth never returned to the hit making status they enjoyed in their early-70s heyday, but they never stopped filling rooms or rocking crowds either. Although Bridges remains the sole original member, most of the current line-up, including guitar player Ray Monette who joined the band in 1971, have been with him for 20 years or more. In 2008 Rare Earth self-released A Brand New World, their first album of new material in over 30 years. A true-to-form collection of R&B-tinged rock, the album won the band critical acclaim and has quickly become a fan favourite.

“We’ve still got the Rare Earth sound and feel,” Bridges says. “That was the most important thing, for me, when we decided to do a new record. I wanted to make sure it sounded like classic Rare Earth. And it does.” While they no longer keep the punishing tour schedule they did in the 1970s, the band still regularly play casinos, fairs and festivals, and the 68-year-old Bridges sees no end to the band he’s kept together for nearly 50 years.

“I just feel totally blessed to still be here,” he emphasises. “To see generations of families coming out to see us, it’s just a great feeling. Black, white, all kinds of people. I would never have expected it. I remember back in the early days, people were always saying to me: ‘What are you going to do when it’s all over?’ I’d say: ‘I dunno. I’ll figure it out.’ Luckily I haven’t had to worry about that yet.