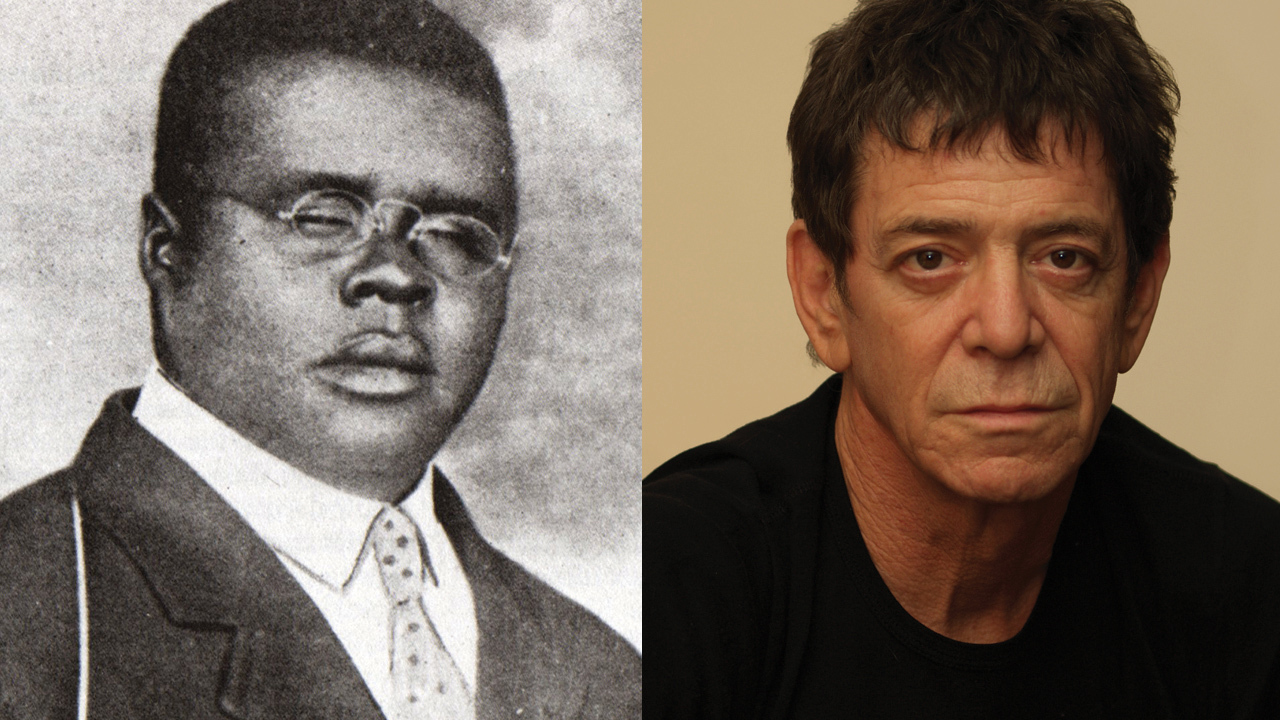

Though the title has the admonishing tone of a moral message, more plausible from a preacher than from a blues singer, See That My Grave Is Kept Clean is a blues with a history spanning nearly 90 years, from Blind Lemon Jefferson to Lou Reed. In its original version it’s a compilation of 16-bar blues verses about death, burial and commemoration: the two white horses that take the body to the cemetery, the grave dug with a silver spade, the body lowered on a golden chain, the sound of dirt falling on the coffin, the toning of the church bell. The central message is delivered in the opening verse: ‘It’s one kind favour I ask of you – see that my grave is kept clean.’

Blind Lemon Jefferson first recorded See That My Grave Is Kept Clean for Paramount Records in late 1927, then again in February 1928 in superior studio conditions. (It’s the second version that’s generally chosen for reissue.) He’s often credited with writing it, though he receives no composer’s credit on the original 78s. One line, at least, he certainly did not write, for it occurs in a song published in 1876, when Jefferson was only in his teens: See That My Grave’s Kept Green by Gus Williams, a German-American actor, comedian and songwriter. Most of the song is commonplace Victorian verse from the dying bed – ‘Thinking of days that have been… leaving forever this scene’ – but there is a recurring refrain, ‘This one little wish I ask of you – see that my grave’s kept green.’ This is all that Jefferson, or someone before him, took from the published song, and in the process “green” became “clean” – maybe because grass doesn’t retain its colour long in a southern climate, or perhaps because there’s a folk belief that it’s disrespectful not to give a gravestone a regular sweeping.

At any rate, Jefferson’s “clean” has been echoed by all his legatees. Surprisingly for a song that sold well on records in the 20s, See That My Grave Is Kept Clean was not covered by any contemporary artist. Son House claimed he had cut it at his one Paramount session in May 1930, but there was no evidence that such a recording had ever been issued. However, for years there had been a tantalising entry in an old catalogue: Clarksdale Moan coupled with Mississippi County Farm Blues, sung by Son House on Paramount 13096. Few copies of any of House’s 78s have survived, and this one appeared to have gone permanently missing – until a copy showed up in 2005, whereupon it was revealed that Mississippi County Farm Blues was set to the melody of See That My Grave Is Kept Clean.

Much of House’s song is a hard-time jailhouse blues, but he seems to run out of inspiration and spends a couple of verses just moaning. Then, in the final stanza, he recalls the song at the back of his mind and signs off with Jefferson’s verse about the toning bell, though it may not be a church bell he’s thinking of, but a prison bell summoning him to work. House’s performance on this track is extraordinary. Little more than two years had elapsed since Jefferson’s record was issued, but his Mississippi contemporary had mastered the jittery Morse code of his guitar style. House still remembered some of it a dozen years later when he recorded a different County Farm Blues, though with the same melody, for Alan Lomax, collecting for the Library of Congress. Compared with the earlier recording, though, it’s sedate. On Mississippi County Farm Blues, House produced the fastest and most explosive guitar playing he ever committed to record. But for the survival of that lone 78, we might never have guessed he could do it.

Another version of Jefferson’s song was caught, again by the roving song-scouts of the Library of Congress, actually on a “county farm” – in other words, state prison facility – in Brazoria, Texas, south of Houston, in 1939. One of the inmates was an extraordinary singer with a deep, brooding voice and a touch on guitar that perfectly complemented it. Smith Casey’s Two White Horses Standing In A Line uses five of Jefferson’s seven verses, repeating the ‘Did you ever hear that coffin sound?’ line to replicate the sound with a vroom on his slide guitar.

A dozen or so years later, another singular bluesman recalled See That My Grave Is Kept Clean. He was a man who had known Jefferson and, living in Houston, could conceivably have known Casey. But Lightnin’ Hopkins’ One Kind Favor, even more than House’s prison restagings, shifts the scene away from the graveside. ‘One kind favour I ask of you,’ he begins, only to swerve into ‘See that my love will come through.’ ‘Bowed down last night on my bended knee,’ he continues, ‘no peoples in the world seem to care for me.’ No longer a meditation on the end of life, this has become a song about the end of – what? Love, perhaps? Or hope?

Meanwhile, the germ of the song had a parallel existence in bluegrass, as Six White Horses, a 12-bar blues that was first recorded by Bill Monroe & His Blue Grass Boys in 1940. The group’s singer, Clyde Moody, like Hopkins, relocates the piece in the world of the living rather than the dying, the horses – which in the original song pulled the hearse – are now symbols of the forces that pull lovers apart.

The 60s blues revival hadn’t much time for Blind Lemon Jefferson. The thumping duple rhythms of the great Mississippi bluesmen like House and Charley Patton seemed more magnetic than the Texan’s dancing triplets. But there’s something peculiarly gripping about the sombre scenes and chiming guitar figures of See That My Grave Is Kept Clean, and this piece from his repertoire, at least, commended itself to practitioners such as John Hammond, who recorded it on his first, eponymous LP in 1963, and later to Kelly Joe Phelps.

To anyone familiar with Phelps’ brooding sound-world, See That My Grave Is Kept Clean would seem a natural choice for him, and on his 1996 album Roll Away The Stone, he takes it on. Amid shimmering slide guitar figures, he moans and murmurs the story of the one kind favour, the silver spade and the church-bell tone. As so often in his work, the tone colours seem to echo the music of another great predecessor, the gospel singer Blind Willie Johnson – like Jefferson, a Texan. Typically, though, his sources and influences are shaped to produce a finished piece that is wholly individual and wholly absorbing.

Highly personal though it is, Phelps’ interpretation remains in a recognisable mould. You could hardly say that of another 90s reconsideration of See That My Grave Is Kept Clean, by Diamanda Galás. To the pulse of a repeated low organ note, the Greek-American singer shrieks and snarls Jefferson’s death chant like a distraught mourner at the graveside. A skeletal organ figure, eerie and wavering, also introduces our last and, perhaps, most unexpected recording. It was made for Wim Wenders’ The Soul Of A Man, the second of the films in the 2003 US TV series Martin Scorsese Presents The Blues. Though Wenders was preoccupied with other figures than Jefferson, such as Blind Willie Johnson and Skip James, he did commission a performance of See That My Grave Is Kept Clean – from Lou Reed.

Let us stop for a moment and look squarely at this song, for it looks squarely itself at the last thing anyone will experience, the journey from which no traveller returns, “The anaesthetic,” in the words of Philip Larkin, “from which none come round.”

So naturally See That My Grave Is Kept Clean summons a special intensity from everyone who performs it. At first, Reed’s delivery is calmer than Diamanda Galás’ distraction, less inward than Kelly Joe Phelps’ monk-like contemplation, but gradually the tempo becomes more insistent, the guitar creaking like a door in a draught. The song is getting to him. Its bleakness sinks into his bones. (The issued recording lasts around five minutes, but a full version more than twice as long can be found on YouTube.)

From Blind Lemon Jefferson to Lou Reed is a long and winding journey. Those two, or six, white horses will be exhausted, but given what this song is about, we know they’ll be called into service again, for this is a song for all time. And although it has drawn an extraordinarily mixed and gifted gathering of reinterpreters, and will surely go on doing so, we feel that the master version, the starting point for any revisionary, is still Blind Lemon Jefferson’s concentrated, undramatic and compelling one. His own grave in his hometown of Wortham, Texas, was unmarked for a long time, before finally being acknowledged with a stone in 1997. The stone, in turn, acknowledges in its inscription what may prove to be his most lasting song: “Lord it’s one kind favor I ask of you – see that my grave is kept clean.”

Death records

The uncertainty of black American life was constantly reflected throughout the lyrics of black music. Today we’re far more squeamish about illness and death, but for Blind Lemon Jefferson, the first southern guitar playing blues singer to make a name on records, they were everyday concerns and therefore they were material for songs. Among his recordings are ’Lectric Chair Blues (the reverse side of his 1928 See That My Grave Is Kept Clean), Hangman’s Blues, Pneumonia Blues and Gone Dead On You Blues.

In addition, there were many passing references to death in the lyrics of many of his other songs. A blues hit of the late 1920s was by a fellow Texan, the singer and pianist Victoria Spivey, who recorded the track TB Blues. Meanwhile, the record-star preacher Reverend JM Gates sold nearly a quarter of a million copies of his Death’s Black Train Is Coming.