Whose version of Little Red Rooster is better: Howlin' Wolf's or the Stones'?

It’s the song that has ruffled feathers from the moment it first appeared, but did The Rolling Stones or Howlin' Wolf create version of has the most to crow about?

Little Red Rooster by The Rolling Stones holds a unique place in British music history. It’s the only recording of a blues song that has ever topped the pop chart. It wasn’t there for long, just one week in December 1964, but for a while during that winter you could turn on your radio and hear about a rooster who was ‘too lazy to crow for day’. ‘Dogs begin to bark, hounds begin to howl… Watch out, strange cat people’ – or something like that: we’ll come back to this – ‘little red rooster’s on the prowl.’ All set to swoops of deep Mississippi slide guitar. And all modelled on a three-year-old recording by Howlin’ Wolf.

YOU CAN SAY of the blues, as the News Of The World used to proclaim of itself, “all human life is here,” but you would have to add, “And a lot of animal life, too.” Dogs, cats, pigs, horses – blues singers have always been preoccupied with critters.

Blind Lemon Jefferson had a whole menagerie of them: Black Horse Blues, Balky Mule Blues, Maltese Cat Blues, Chinch Bug Blues (a chinch is a bedbug), Mosquito Moan, Black Snake Moan. Son House had a Shetland Pony Blues, Charley Patton a Jersey Bull Blues, Robert Johnson a Milkcow’s Calf Blues. Barbecue Bob even had a Black Skunk Blues.

There are blues about bluebirds and boll weevils, frogs and alligators, bearcats and black rats, heifers and hound dogs and, thanks to Bo Carter, many about pussy. You could make an entertaining compilation of them, The Bestiary Of The Blues.

It would have to open the gate wide for poultry. In the 20s, Lonnie Johnson’s Crowing Rooster Blues and Charley Patton’s Banty Rooster Blues set the scene of a cocky cockerel and his flock of obedient hens, a farmyard version of the pimp and his hos.

Howlin’ Wolf had heard Patton firsthand and may have remembered Banty Rooster Blues. His own rooster blues had a different melody and mostly different words, but he shared with Patton the idea of a rooster who won’t crow for day. The composer credit, as so often on Wolf’s records, went to Willie Dixon, once again drawing on his vast recall of blues and black folk speech. Chess Records titled it The Red Rooster and issued it as a single in the autumn of 1961.

The song then caught, or was brought to, the attention of Sam Cooke, who recorded it in 1963 as Little Red Rooster and got it, as Wolf had failed to do, into the American charts: Top 10 in the R&B list, even Top 20 pop. Wolf’s stark melody line, drawn in bold felt tip pen strokes by his own slide guitar and Hubert Sumlin’s electric, is on Cooke’s recording thickened by organist Billy Preston. There’s a subtle difference in the storytelling too. Wolf begins, ‘I am the little red rooster.’ Cooke distances himself from the bragging: ‘I got a little red rooster.’

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

But the next recording of the song put the narrator back, front and centre. ‘I am the little red rooster,’ declares Mick Jagger. (No kidding.) Brian Jones finds a different angle on the slide-guitar part, but the Stones’ 1964 recording echoes Wolf’s in its use of space, the singing backed by just a couple of guitars, a drum pattern and the simplest of bass guitar figures. Only at the end does a harmonica take up the story.

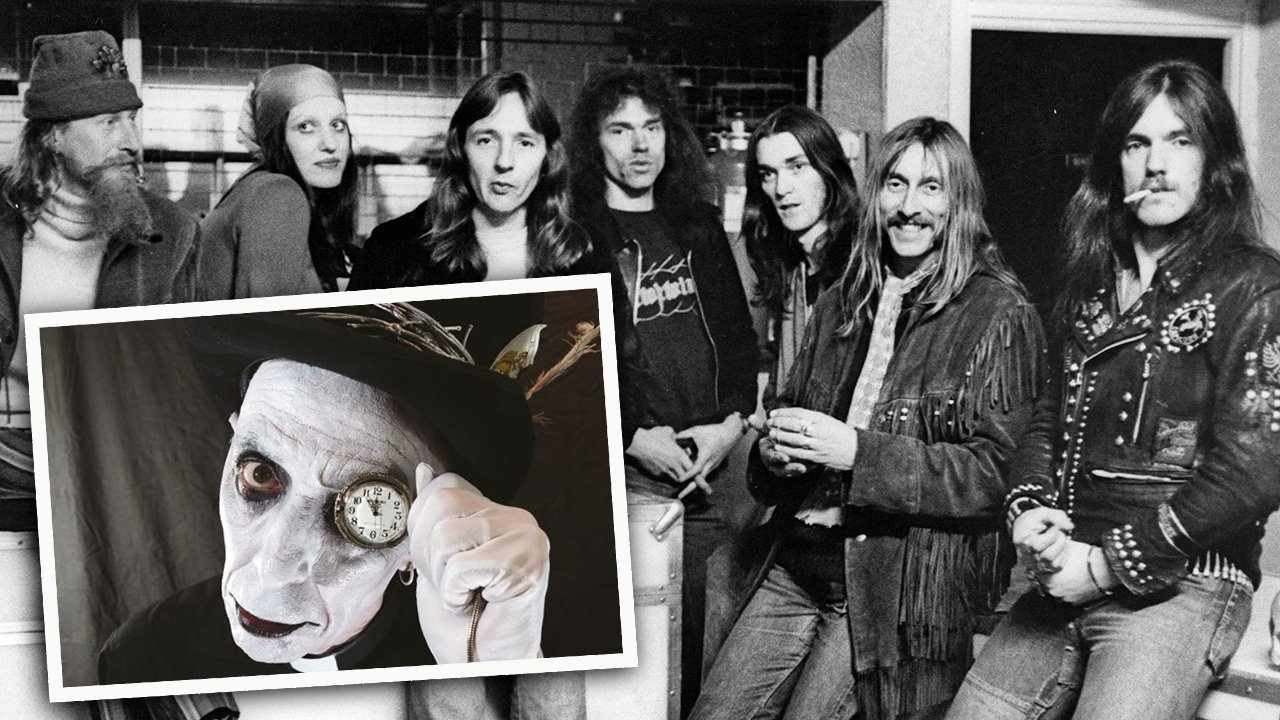

The group must have heard Wolf’s record, though they would have had to go to some trouble to do so, since it hadn’t been issued in the UK (and, oddly, wouldn’t be for many years). An imported copy of Chess LP 1469, Wolf’s famous “rocking chair album”, might have been their source. But they may also have been prompted to consider the song by an encounter with its composer. Their then-manager Giorgio Gomelsky (who died earlier this year) recalled for Willie Dixon’s biographers how the big man used to distribute his songs among the British R&B community, and even demonstrate them.

Gomelsky, the owner of the Crawdaddy Club, later remembered “Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy [Williamson II] and Willie Dixon, the three of them sitting on this sofa… Willie was just singing and tapping on the back of the chair and Sonny Boy would play the harmonica and they would do new songs. To a degree, that’s why people know those songs and recorded them later. I remember 300 Pounds Of Joy, Little Red Rooster, You Shook Me were all songs Willie passed on at that time… Jimmy Page came often, The Yardbirds… Brian Jones.” If Gomelsky’s memory was accurate, this would have to have been in October 1964, when all three bluesmen were in the American Folk Blues Festival troupe that passed through the United Kingdom. But the Stones had begun recording Little Red Rooster almost two months earlier, so the Dixon–Stones connection must go back farther. The AFBF, with Dixon always present, had been visiting the UK since 1962, and Jones, at least, would have been in the audience every year.

Many of Dixon’s songs included southern black phraseology that would have been exotic to the young British musicians contemplating covering them: mojos, hoochie coochie men, tail draggers, wang dang doodles.

Which brings us back to those ‘strange cat people’. This is what Jagger appears to have heard in Wolf’s second verse: ‘Watch out, strange cat people’ – or maybe ‘strange kinda people’ – ‘little red rooster’s on the prowl.’ But in Wolf’s recording it sounds more like ‘strange kin people’, whatever that might mean.

To get to the bottom of the mystery, we called blues vocabulary expert Chris Smith, and after poring over the sound files and consulting dialect dictionaries, we have what may be a solution. What Wolf actually sang was ‘Watch out, straying kinpeople’ – “kinpeople” being a widely documented southern variant of “kinfolk”. (Sam Cooke sang “kinfolk”.) The rooster is giving notice to his extended family – the hens – not to go wandering off by themselves. Big Daddy is doing his rounds.

It wasn’t only the Stones who were thrown by the unfamiliar word “kinpeople”: almost every subsequent recording of Little Red Rooster – and there have been many – has undergone a rewrite. Big Mama Thornton, in her 1965 London recording, sang, ‘Watch out, all you girls,’ while Luther Allison, on his 1969 debut album Love Me Mama, opted for ‘Watch out, all you good people’. Hubert Sumlin and Willie Dixon, who were closer to Wolf than most (and were on the original recording), evaded the problem by recasting the line entirely. Otis Rush’s 1977 version has ‘Watch out, all you kinfolks’, because Rush was remembering how Sam Cooke had sung it. But we do find confirmation of Wolf’s “straying kinpeople” in the 1993 recording by Big Daddy Kinsey.

Wolf himself revisited the song several times, first in 1969 for the infamous freakout LP The Howlin’ Wolf Album – the one that said on the sleeve, “This is Howlin’ Wolf’s new album. He doesn’t like it. He didn’t like his electric guitar at first either” – and next in 1970 during the recording of his London Sessions. The timing of The Red Rooster as Wolf does it is tricky, with extra beats in what would otherwise be a straightforward 12-bar blues, so he demonstrates to Eric Clapton and the other British musicians present how it’s done, and they urge him to play on the recording itself so that they can follow him. “I doubt if I can do it without you playing,” says one of them, maybe Clapton himself. “Oh, man, come on!” Wolf genially replies.

Although Wolf invested all his recordings of the song with huge personal presence – you can really believe in him as a red rooster, and not a little one at that – this did not deter other singers from reshaping it to their own designs. From the 70s, there’s a dead-slow, brooding version by Luther “Snake Boy” Johnson and Johnny Shines, and a more edgy one by Willie Kent.

Several pianists have adopted it – Henry Gray, who played with Wolf (though not on The Red Rooster), Big Joe Duskin and Willie Mabon, who uses it for a Sam Cooke tribute. More recently there have been versions by Chicago blues singer Demetria Taylor, Mississippi throwback T-Model Ford and Robin Trower (on his 2010 CD Roots And Branches). It’s been done, too, by The Doors and the Grateful Dead. Although the first time round it didn’t really fly, the song now roosts in the spacious chicken coop of blues standards.

For that the Stones must surely take some of the credit. But do they also take the biscuit? Which is the winner in this cockfight? It’s a tough one. Wolf lends the song gravitas; in comparison, the Stones sound like cheeky youngsters. But then, of course, that’s exactly what they were, and they were never the sort of blues fans-cum-musicians who wanted to sound like senior citizens before their time. Their Little Red Rooster is all about being young and sexy, the cock of the walk. Wolf’s rooster is an older and scarier entity, forever on the prowl – very much like a wolf, in fact, but shapeshifted from fur to feathers. Some ears will resonate naturally to this expression of raw animal magnetism, others to the slinkier charms of The Rolling Stones.

Call it a draw.

The 5 Best Howlin' Wolf Songs, by Black Stone Cherry's Ben Wells

A music historian and critic, Tony Russell has written about blues, country, jazz and other American musics for MOJO, The Guardian and many specialist magazines. He has also acted as a consultant on several TV documentaries, and been nominated for a Grammy three times for his authorship (with Ted Olson) of the books accompanying the Bear Family boxed sets. He is the author of Blacks, Whites and Blues (1970), The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray (1997) and Country Music Originals: The Legends and the Lost (2007).