Cuttin' Heads: Please Set A Date

Memphis Minnie vs Elmore James vs Erja Lyytinen

Memphis Minnie’s lusty classic has been getting blues musicians hot under the collar for decades, but whose version pops our cork?

It’s all about sex. ‘Baby, please set a date. Don’t set tomorrow – tomorrow is too far away.’ The blues are not known for being tight-lipped about getting it on, but these lovers are unashamedly gagging for it. ‘Now when I wants my lovin’, yes, I wants it bad …’ Even their expressions are contorted by lust. ‘When I get you in my arms, my face gets full of frowns – baby, if you don’t hurry, I’m gonna leave your town …’ In fact, they are losing themselves in each other: ‘I love you so much, baby, I love you better than I do myself.’

Get a room, for goodness sake!

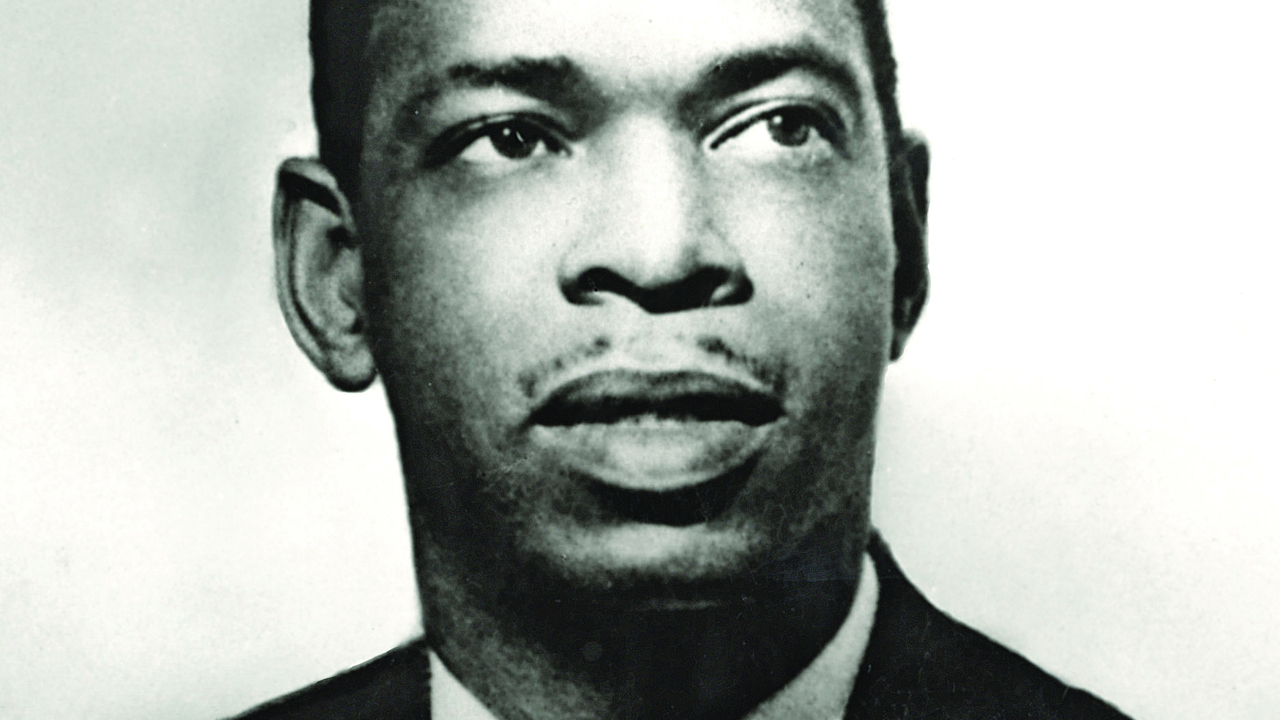

For most blues musicians, Please Set A Date begins with Elmore James in 1959. His swooping, clattering slide-guitar intro prefaces, as it so often does in his music, the testament of a desperate man. But this time he isn’t wailing that the sky is crying, or that he believes he’ll go back home, or that his time ain’t long, or that he’s going to dust his broom. This is the desperation not of loss but of desire, perhaps even obsession. ‘If you ever leave me, baby, I couldn’t love nobody else.’

But this is not where the song began its life. It first appeared 15 years earlier on a record by Memphis Minnie. This skilful operator had been steering her course through the blues for a decade and a half, shifting gears from the intricate manoeuvres of her acoustic guitar duets with Joe McCoy to the hard-driving blues-band sound of the late 30s and 40s. Her 1944 recording of Please Set A Date is bare-bones blues, just an electric guitar, a hardly audible rhythm guitar and drums. You feel the beat, but your attention is directed to the lyrics. ‘Ah, daddy, daddy, please set a date,’ she begins, and the line returns as a refrain after each verse, ending, urgently: ‘Don’t set tomorrow, cos tomorrow’s too far away.’

Ever since she sang, on her first hit record in 1930, about a bumble bee with a stinger as long as her right arm, Memphis Minnie had been a spokeswoman for sex. So, of course, were her contemporaries such as Bessie Smith or Lucille Bogan, but they tended to be declamatory in style, big mamas with attitude. Minnie, in the personality she showed on record, was a little more subtle, sometimes even come-hitherish. In Please Set A Date she doesn’t so much confront her lover as cajole him (‘ah, daddy, daddy …’).

There’s more at stake here than simply a hot date. Despite the eroticism of the song – ‘when I wants my lovin’ … when that feelin’ strikes me …’ – Minnie is realistic about how the affair is likely to play out in the long-run. ‘We first left home, we’s sworn not to part/But the way you’ve been doin’ is really breakin’ my heart.’ It’s as if she can foresee a time when she’ll ask him for a date and all he’ll get out will be his diary.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

So in Minnie’s hands this becomes an emotionally ambivalent song. She may get what she needs right now – tomorrow, remember, is too far away. But when tomorrow comes it may find her rueful, reflecting, like another articulate woman who had no illusions about men, Dorothy Parker: “I doubt if this will get me much.”

Elmore James may have heard Minnie’s record, or caught her singing Please Set A Date around the clubs when he first came to Chicago. However he came by the song, he made something simpler of it, stripping it down, dropping a couple of Minnie’s verses and adding one of his own. But some of those rejected lyrics show up in later recordings of the song, even ones by musicians who must have heard Elmore James’, so we must look for someone else who might have remembered Minnie’s text. Someone like Elmore’s cousin Homesick James.

Homesick evidently liked Please Set A Date, since he recorded it several times over more than 40 years, first for a small Chicago label, Colt, in 1962, and last on his 2004 album My Home Ain’t Here. His slide playing was always less tempestuous than Elmore’s, closer in a way to that of their common model, Robert Johnson, and that 1962 single (issued in the UK on Sue three years later) has a pleading quality, less bang-on-the-table demanding than Elmore’s.

Another recording made around this time dispensed with slide guitar altogether. In 1960 BB King filled a studio booking for Modern Records that would result in an album on the budget-priced Crown label called My Kind Of Blues. Accompanied only by a trio of piano, bass and drums – the pianist the dependable Lloyd Glenn – BB sailed through a setlist of what either were or would become blues standards, creating one of his most perfectly realised albums. As he liked to recall with amusement in his later-life interviews, BB never acquired the skill of playing slide guitar; arguably it was his inability to do so that helped to form his own highly vocalised guitar style. So he gives us a Please Set A Date that sidesteps the Jameses and recalls Memphis Minnie, whose version it reproduces undeviatingly, verse by verse.

Nevertheless, it was the readings of the song by Elmore and Homesick James that were its points of reference in the later 60s. Minnie’s recording was known only to collectors, and in the UK that was also true of King’s, but in any case they both lacked the appeal of a propulsive slide-guitar figure. It was that steely shimmer that caught the eye of Fleetwood Mac, who cut it at a 1967 BBC session, featuring the vocal and slide guitar of Jeremy Spencer, a devotee of Elmore. Another Jamesian version of the song is the one by George Thorogood on Move It On Over (1978), the second of his miraculous Rounder albums. In the hands and mouths of personable young men such as these, Please Set A Date became a manifesto of machismo, a summary summoning of the accommodating girlfriend: ‘When I wants my lovin’, yes, I wants it bad.’ Or, as Kinky Friedman put it, get your biscuits in the oven and your buns in the bed.

But there were other ways of putting the song across than as a mating call for the young and randy. James Cotton, for example, reimagined it as a genial chant with stabbing horns and a shuffle beat. You don’t hear a lot about Cotton these days, but in the late 60s and 70s he was a favourite on the college and hippie blues circuits and some of the music he made then has more durability than you might expect. The 1968 Vanguard album Cut You Loose!, though it boasts no big-name sidemen and has a definite whiff of its time as distinctive as patchouli oil, has been described as “approachable and uncomplicatedly enjoyable”, and we certainly approve that judgement. Among its tracks is Set A Date, and it’s the most upbeat and easygoing of all the versions we’re listening to.

Robben Ford, too, has visualised Please Set A Date without its familiar slide-guitar figures; his version on the 2009 live album Soul On 10 gets a couple of verses out of the way and settles into a long sequence of solos on keyboards and then guitar before seguing into Jimmy Reed’s You Don’t Have To Go. By this point – and this is something that happens to a number of blues standards – not much of the original survives beyond a title phrase.

But not long afterwards came another and more by-the-book version, which is no more than you would expect of Elmore James Jr, who, like Mud Morganfield, has made a decent career out of stepping carefully – and, to be fair to both men, adroitly – in his father’s footprints. James Jr’s Baby Please Set A Date was the opening and title track of his 2010 Wolf album.

Four years later, the Finnish singer and guitarist Erja Lyytinen added another version to the portfolio. It came on her album The Sky Is Crying, an all-out tribute to Elmore James, but her Baby Please Set A Date breaks daringly away from the master’s model. Though lyrically she tracks his recording faithfully, just adding a few repeats of the title verse, the mood she creates is quite different from what went before, a sultry, if unspoken, promise of silken sheets. It is insinuating, sexy, yes, all of that – but also empowered. When the narrator holds her lover in her arms and her face gets full of frowns, they will be frowns not of dissatisfaction but of concentration on the job at hand. It’s the song of a woman who knows what she wants and how to get it, and is straightforward about saying so. In short, Erja Lyytinen reclaims the song as Memphis Minnie would recognise it, but she gives us something more than Minnie, or Elmore James, could have offered: a Please Set A Date for the modern woman. ‘Tomorrow is too far away.’ You could use that line on Tinder.

A music historian and critic, Tony Russell has written about blues, country, jazz and other American musics for MOJO, The Guardian and many specialist magazines. He has also acted as a consultant on several TV documentaries, and been nominated for a Grammy three times for his authorship (with Ted Olson) of the books accompanying the Bear Family boxed sets. He is the author of Blacks, Whites and Blues (1970), The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray (1997) and Country Music Originals: The Legends and the Lost (2007).