“Hello little schoolgirl! Good morning, little schoolgirl! Can I go home with – can I go home with you?’ The singer, aptly enough, was called Sonny Boy: John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson. It was May 1937, and he was making his first record. It would turn out to be the song most closely associated with him, but it would also become a blues standard, covered by contemporaries such as Smokey Hogg, John Lee Hooker and Lightnin’ Hopkins, and in the next generation by Paul Butterfield and The Yardbirds, and it is still a well-thumbed page in the blues songbook.

Today, a song about chatting up a schoolgirl could be a high-risk item, so let’s be clear about it: this is not a dirty-old- man scenario but a meeting of equals, chirpy and innocent. ‘Now you can tell your mother and your father,’ the singer continues, ‘that Sonny Boy’s a little schoolboy too!’

He was, in fact, 23, but in early recordings like this he sounds engagingly boyish, sometimes stammering in his enthusiasm, so that repetitions like ‘Can I go home with – can I go home with you?’ make his blues feel a little like children’s songs, going round and round like the wheels on the bus.

Taking their cue from that opening verse, either Sonny Boy or Bluebird Records titled the song Good Morning, School Girl. (No Little on that first recording.) And yet, mystifyingly, having been gifted with what may have been the best idea of his life – the neat and, so far as blues are concerned, original setting of school kid courtship – Sonny Boy throws it away. He never mentions school again.

The next verse is a blues commonplace about waking up in the morning feeling ‘all messed up in mind’. The two that follow are addressed to a girlfriend, but in very different terms. Be my baby, he wheedles her; be my baby, and I’ll buy you a diamond ring. And in the next verse he says he’s going to buy an airplane so that he can fly around until he locates her. We’re not in school any more. These purchases are not coming out of his pocket money.

Perhaps the song isn’t quite as disjointed as it seems. Maybe we can read it as a compressed story about growing up, from schoolboy crush to adolescent angst (‘messed up in mind’) to adult decision-making (the diamond ring) to aspiration (the airplane). If so, the tale ends in uncertainty: ‘I don’t know hardly what in this world to do.’ The airplane tumbles out of the sky and crash-lands on the solid ground of what Sonny Boy could expect out of life.

A citizen of the unfree state of black America, he was unlikely ever to have the money for diamonds, even if he lived long enough to save it. In fact he died at 34, mugged and stabbed with an ice pick on the short walk home from the Chicago club where he was playing.

The year before, in 1947, his signature song had been revived by an admirer, the Texan singer and guitarist Smokey Hogg. He began with Sonny Boy’s opening verse, then jumped to the airplane, then took off on a new flight, steering the song somewhat back towards its core idea: he calls his girl his ‘baby child’, and the last verse begins ‘Remember way back?’.

To many blues enthusiasts today, Hogg is a puzzle. His songs are often loose and unfocused. As a guitarist his pitch was unreliable, his playing angular and awkward, his timing shaky. The musicians accompanying him are often audibly at a loss. Yet none of this can have mattered in his own time. He was courted by several labels and made dozens of records. Little School Girl, as his version of Sonny Boy’s song was titled, reached the Top 5 on the Billboard R&B chart.

That would have helped to settle the song in the blues repertoire, and by the end of the 50s it had become a standard. It was one of many that John Lee Hooker recalled while making his acoustic “folk blues” albums for Riverside in 1959. His Good Mornin’, Lil’ School Girl is, by his lights, remarkably faithful; he uses four of Sonny Boy’s five stanzas and even preserves some of the rhyming, a device he dispensed with in his own compositions.

School Girl was embraced by numerous blues singers of Hooker’s generation, though some of them had to wait longer to have a chance to record it, such as James “Son” Thomas and Eddie Cusic from Mississippi or Frank Edwards from Georgia. In Chicago, Smokey Smothers recorded a Hello Little School Girl (1962) but discarded almost all of Sonny Boy’s original lyrics and performed it in the dead-slow, zonked-out style of Jimmy Reed. Junior Wells cut it on his album Hoodoo Man Blues in 1965, and Lightnin’ Hopkins did a characteristically free-spirited version in 1969.

The song was also taken up by the first wave of white bands in the 60s. The Paul Butterfield Blues Band gave it a very brisk run-through during a 1964 session for Elektra that wasn’t issued until 30 years later in Britain.

But before we go there, let’s take another look at this song that isn’t what it seems.

For Sonny Boy Williamson it begins with the winsome picture of kids eyeing each other up on the way to school. But, as we’ve seen, the image is frozen there; the rest of the song time-shifts into adult life. Still, it’s a strong hook, and virtually everyone who’s recorded the song has kept hold of it. But, for a long time, no one seemed to have thought about strengthening it. Given the setup, it would be an obvious next step to have the boy carrying the girl’s books for her (Lightnin’ Hopkins did think of that), then maybe sitting next to her in class, buying her a soda at break time – in short, writing it as a Chuck Berry song. But that would scarcely have been possible in 1937.

The teenager, as Chuck – or we – would understand the term, did not exist. Most black children in the south (Williamson grew up in Jackson, Tennessee) were barely into their teenage years before they were out of school and into work. Education that continued through high school, the underlying premise of Berry’s songs like School Day or Oh Baby Doll, was a luxury affordable only among middle-class African-Americans, whose family income was not dependent upon their children labouring in a cotton field.

Perhaps, too, a fully developed song about school-age romance wouldn’t have caught on with the people who then bought blues records. The blues is many things, but it is seldom romantic and never cute. Chuck Berry’s vision of soda fountains and high-school dances was only made possible by change: change in African-American life, but also change in the larger society, where teenagers as a group now constituted a viable market for music attuned to their lives and interests.

And now we can come to the UK. It is 1964, the era of the beat boom and the R&B explosion. Musicians in their teens and early twenties are poring over American discs bearing the labels of Chess and Vee-Jay, or sampling vintage sounds of the 30s and 40s, as captured that very year on the UK release Big Bill & Sonny Boy, an LP assembling recordings by the two artists. Sonny Boy’s best-known song was not among them, but it had been reissued on a French EP a year earlier. But when The Yardbirds – among them Eric Clapton – recorded Good Morning Little Schoolgirl, it was a version created in 1961 by an obscure R&B duo, Don & Bob, which paid almost no attention to the original but buried the melody and Berryfied the lyric.

Here are Chuck’s school hops and the soda shops, and dance crazes like the twist and the stroll. But though the references are American, the ambience is authentically English, the London of Carnaby Street and Twiggy. The 1964 schoolgirl comes home, takes off her gym slip, wriggles into a miniskirt and becomes a dolly bird. That evening, when The Yardbirds play the Marquee, she’ll be in the audience, personifying the girl implied in the song.

People talk about bringing the blues up to date, giving it contemporary relevance, but attempts to do so are often just paint jobs. The Yardbirds’ Good Morning Little School Girl is a transformation. The song has been hauled out of its original, southern, pre-World War II setting and restyled for mid-60s swinging London, overalls and gingham dress exchanged for kipper ties, bell-bottoms and platform soles.

For the time, it was a brilliant redefinition. But it was so much of its time that it has dated, and today it’s more of a museum piece than the original. So our vote goes to Sonny Boy Williamson’s Good Morning, School Girl, with its irresistibly jaunty tune and its implicit invitation to take the lyrics in whatever direction you want to go.

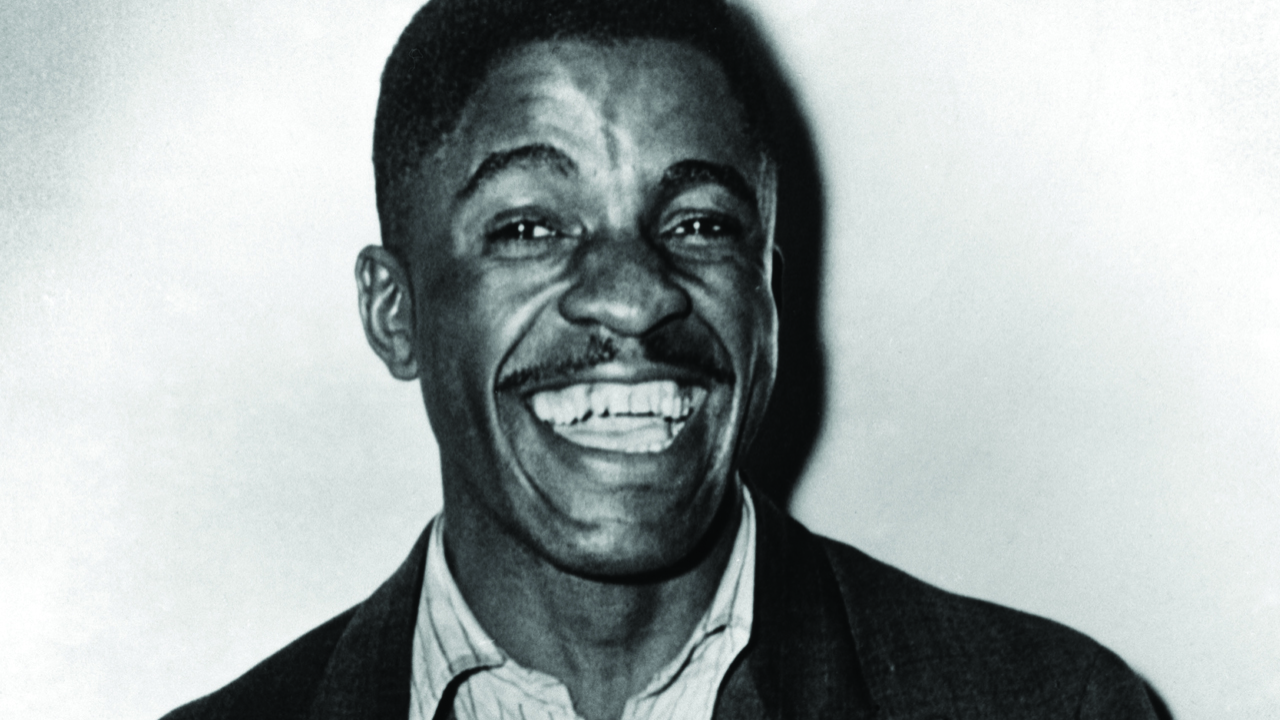

Boxout: The original Sonny Boy…

Sonny Boy Williamson was the primary influence on the northern-based blues singers and harmonica players of the next generation such as Little Walter, Junior Wells and Billy Boy Arnold. So it’s a little disconcerting to listen to the recordings from his first few sessions and find them sounding so southern.

On the original School Girl his voice and harmonica (unamplified, of course) are backed by the guitars of Big Joe Williams and Robert Lee McCoy, and the sound is almost rural. Williams and McCoy, with guitarist and mandolinist Yank Rachell, appear on many of those early sides. But from 1940, when he began recording with drums and bass and pianists like Blind John Davis, his sound became tougher and more urban, and his recordings from this period and later provide templates for the Chicago blues of the 1950s.