Soon after he arrived at my parents’ house in the little village of Lydden near Dover, he acquired a pet. This was a tin can on a long piece of string, which he tied to his belt,” says Robert Wyatt, recalling Daevid Allen’s appearance in his life in 1960.

“Soon after he arrived at my parents’ house in the little village of Lydden near Dover, he acquired a pet. This was a tin can on a long piece of string, which he tied to his belt,” says Robert Wyatt, recalling Daevid Allen’s appearance in his life in 1960. “The tin can, of course, followed him, merrily tinkling away behind as he walked up and down the main road.”

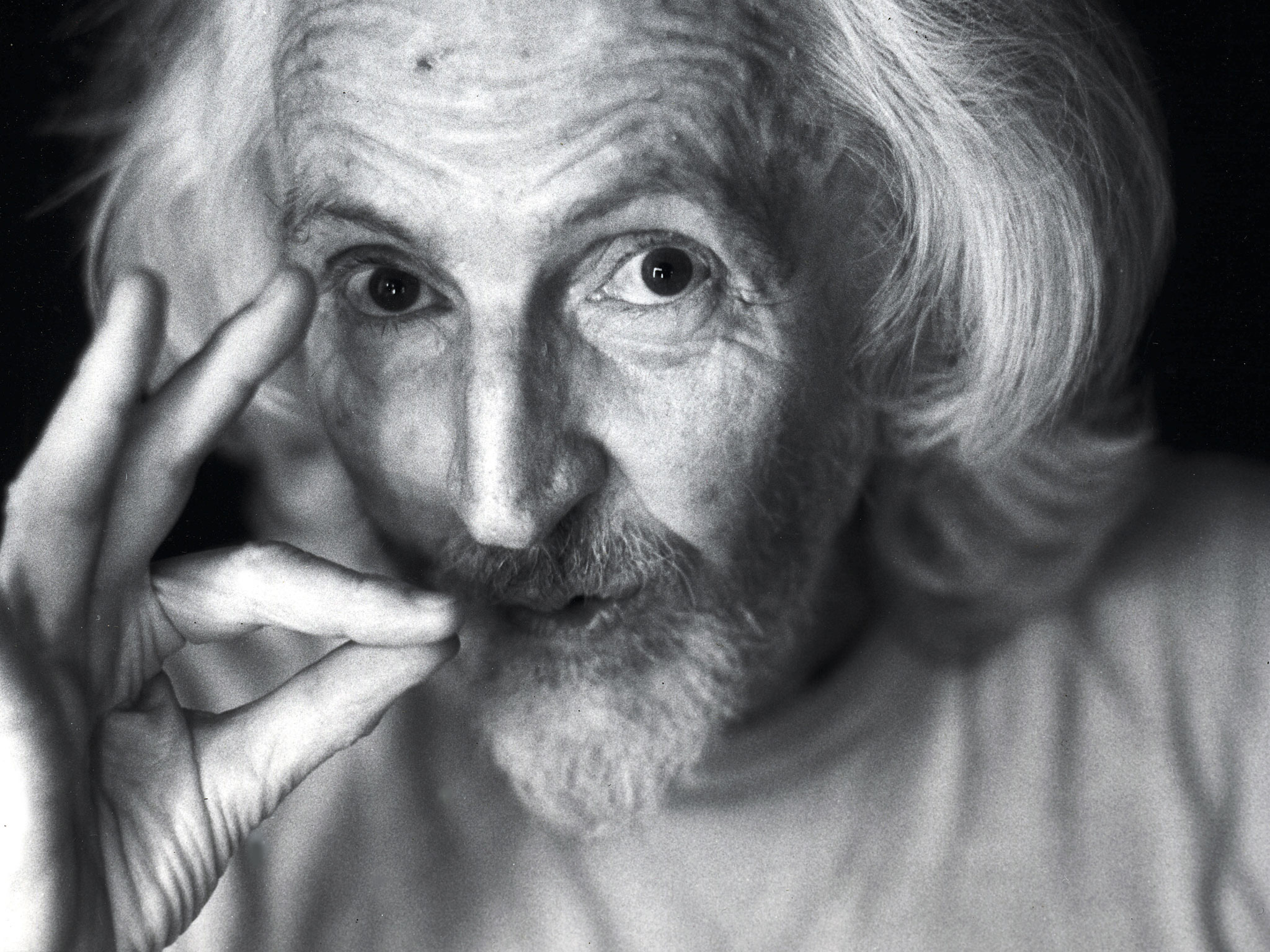

That kind of unconventional and wryly provocative behaviour typifies Allen’s playful yet seditious view of life; a penchant for seeing beyond what’s there or, in this case, what’s not there. Having left his native Australia, an itinerant autodidact on a mission to soak up Europe’s avant-garde counter-culture, first in Greece, then Paris and finally as a lodger in the Wyatt household not far from Canterbury, Allen’s zesty intensity had a liberating effect on many of the people he met.

He certainly made the then 15-year-old Wyatt sit up and take notice. “It was Daevid’s assumption that you could make some kind of life for yourself, outside the ‘straight world’, that inspired me most. Nobody talked about insipid concepts like having a career, or thinking sensibly about our future.”

Poet, artist, aspirant musician with a yearning for free jazz as well as being fully conversant in the works of Beat Generation writers and the psychological and intellectual absurdities of Dadaism, Daevid Allen quickly became a pivotal figure in what was later to be called the Canterbury Scene.

When the opportunity came in 1966 to form a band with Allen, Robert Wyatt, Hugh Hopper, Kevin Ayers and Mike Ratledge jumped at the chance and became Soft Machine. In 1967 after returning from a gig in Europe, Allen was refused re-entry into the UK. With no choice but to remain in France, his charismatic personality once again ensured he became a magnet for adventurous musicians. His next musical collective would eventually coalesce into Gong.

He was often too self-deprecating about his guitar playing. Daevid had a brilliant talent for snatching an almost impossible, angular, wacky, but also catchy, melody.

Steve Hillage

While 1971’s Camembert Electrique marks Gong’s first mature manifestation, Allen’s most enduring legacy is the Radio Gnome Trilogy of _Flying Teapot _(1973), Angel’s Egg (1973) and You (1974).

Alongside the political and spiritual allegory of the Pot Head Pixies and the adventures of Zero The Hero, Allen’s glissando guitar haunts the supple grooves of these albums. Luminous and mysterious, former Gong bassist Mike Howlett believes this aspect of Allen’s contribution has been overlooked. “Whatever else Gong did, at a certain point when you’ve got the groove going and the glissando flying over the top and someone like Didier Malherbe or Steve Hillage soloing, _that _is the defining sound of Gong. That was magical, mystical and it was Daevid’s thing.”

He didn’t play all the clichéd licks. When you heard him let rip on a solo he was everything you could want.

Mike Howlett

In concert Flying Teapot’s cathartic potential was given physical manifestation by the sight and sound of Allen, eyes agog in beatific rapture, and flailing arms frozen in the stark flickering strobe lights intoning, “Flying saucer! Flying Teacup from outer space! Flying Teapot!” Captured in those shuddering black and white poses, looking not unlike some extraterrestrial shaman calling home, he provided the band with a dramatic focus.

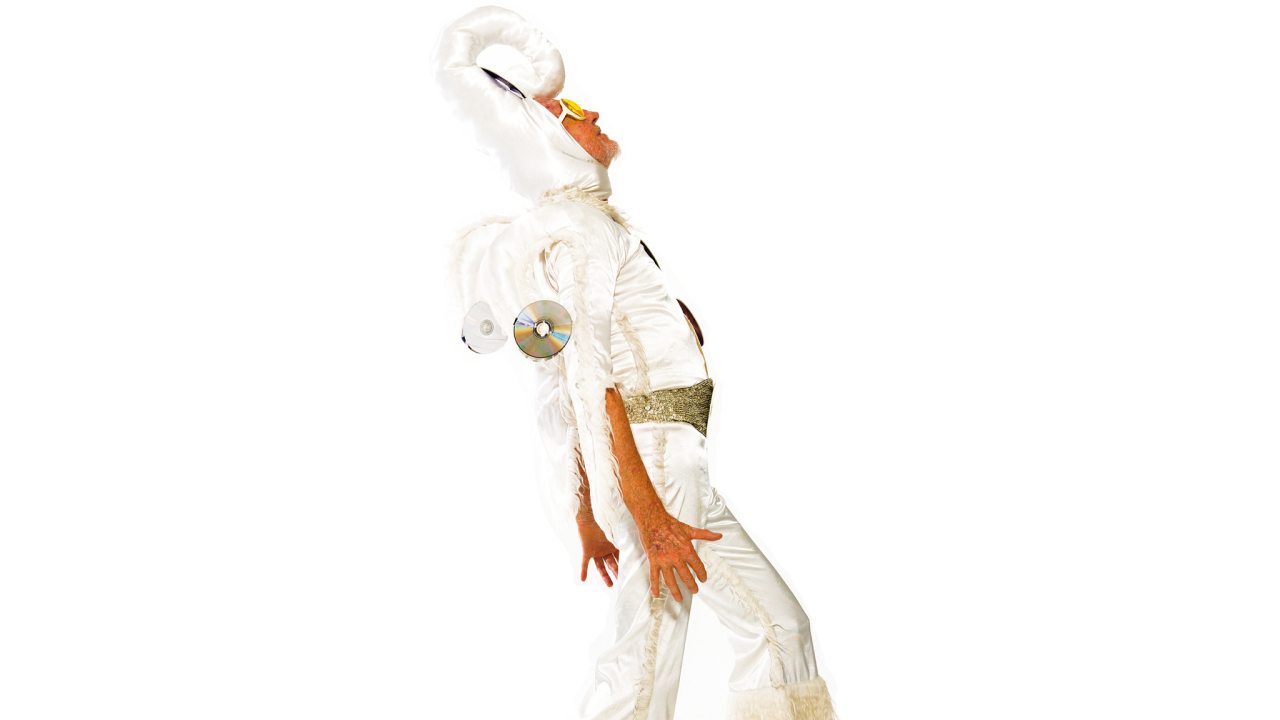

Having the extra musical firepower of Hillage and Howlett in Gong enabled Allen to develop a greater on-stage presence, utilising costumes to heighten and highlight the Zero The Hero mythos and narrative

he envisaged running from Teapot through to You; an idea he admitted was in part validated by seeing Peter Gabriel’s performance in Genesis. While these enhancements provided an outlet for his theatrical bent, their real significance was that they enabled him to define his own unique role within the group. It might sound surprising to anyone who has seen Allen as a larger-than-life presence on stage with or without Gong, but he suffered from doubt about his abilities.

“I think he had a little bit of an inferiority complex about his playing because he was a poet really in his own mind,” says Howlett. “He always felt he wasn’t musical enough. He always felt he had to have somebody like Steve [Hillage] in the band, but I always thought he was a remarkable guitarist and highly original. You look at something like Camembert Electrique, before Steve and I joined, and you’ll see

it wasn’t just us throwing in all the funny time signatures. He didn’t play all the clichéd licks. When you heard him let rip on a solo he was everything you could want – raw power, expression, melodic and fairly angular.”

It’s a point with which Hillage readily agrees. “He was often too self-deprecating about his guitar playing. Daevid had a brilliant talent for snatching an almost impossible, angular, wacky melody - virtually out of thin air. I loved his lead guitar playing. He had a bit of a love-hate relationship with jamming and improvising, but, in fact, he was a great improviser and someone who had been strongly influenced by free jazz. This contrast is reflected in a lot of Gong’s music which oscillates from improvisatory passages to tightly arranged sections.

“I think a good example of Daevid’s qualities is the second half of side two of You, loosely titled You Never Blow Yr Trip Forever,” Hillage continues. “Both for the impossible vocal melodies and for a wacky guitar solo that was often a totally legendary moment in a live Gong set. I have always seen Gong as a collaboration, so I’ve always been happy when Daevid found ways to express himself on track ideas that might have originated through me, either with his vocals or with his glissando guitar. This is also true for Angel’s Egg where a lot of the tracks originated while Daevid was out of the band on a sabbatical in spring 1973.”

Despite those times when he walked away from the industry, Allen’s ability to play in the moment and be a catalyst to those around him was a quality he never lost. Keyboard player/vocalist Yumi Hara played alongside Allen and Henry Cow’s Chris Cutler in a trio, you me & us, in 2013. “Chris and I accompanied him with different rhythms and harmonies,” she recalls. “Usually, it is tricky to change chords spontaneously when improvising in a tonal context, but with Daevid, one could change chords at will. He was always in tune with my accompaniment, from the very first gig. Daevid’s guitar playing and vocal improvisations were so inspirational that I found myself playing things I didn’t know I was able to play.”

Mike Howlett remembers Allen saying in 1974 that his vision for Gong was to create a band that wouldn’t need him or [co-founder, poet/vocalist] Gilli Smyth for its impetus, but that it be a thing of itself that would carry on for generations, what Allen believed was a constructive and ultimately progressive force.

Exactly 40 years later, when Allen spoke to _Prog _in 2014, knowing his time was limited, his view was unchanged. “My greatest wish is that Gong can become a musical tradition and continue to give pleasure, excitement and positive uplift for a long time after I am gone,” he said. With members of the current incarnation vowing to carry on, it looks like Allen’s memory and his music will indeed live on as he wished.

Dear Daevid

Robert Wyatt wrote an email to old friend Daevid Allen just weeks before he died. He shares that last communication with Prog.

Recently, Robert Wyatt came across a collection of clips on YouTube from a 1964 Spanish film, Playa de Formentor, on which he and Daevid Allen had worked as extras. “A couple of hungry young vagrants who’d do anything for enough money to eat on the day,” says Wyatt of their brief scenes together. In one scene, we see the pair talking at a party as a local beat combo plays tame rock’n’roll. In another, as the lead actors get off a ferry, Daevid Allen is in shot, playing a bamboo flute and looking every inch the beatnik. Watching these fleeting appearances of their younger pre-Soft Machine selves prompted Wyatt to send an email to his old bandmate; though the initial impulse was overshadowed by the news that Allen had decided to refuse treatment for his cancer.

**February 23rd 2015 **

Dear Daevid my oldest friend,

Did you see that rather extraordinary little glimpse (on YouTube) of us two but mainly you on this old presumably Spanish film, (Playa de Formentor) – I don’t remember it AT ALL. 1964.

Cor blimey guv, we so brushed up and shiny.

The thing that I also liked so much was a good longish video of one of your groups, a trio.

Your playing is immaculate and your voice so cool in both modern and ancient sense. Riveting. A good reminder of why you have such a mesmerised following.

That was going to be it, but then I heard your most recent news, and your philosophical take on that.

No words when it really matters but I think we’ve shared a lot of memories and love, n’est ce pas?

So thank you for all that inspiration … … . . can’t imagine my life without it.

X Robert