He doesn’t remember the exact date that he hit rock bottom. He was drinking so heavily, and doing so many drugs, that the days and nights were slipping past in a blur. What he does remember is the moment of clarity that came to him as another long night was stretching into the dawn. As he sat alone in a darkened room, he placed his crack pipe on the table before him and stood up to gaze at his reflection in a mirror on the wall. What he saw, he barely recognised. He said to himself: “You’re either going to die any minute now, or you’re going to quit this one day and it will be a story you’re going to tell.”

It was 2002 and Dan Reed, at the age of 39, was lost. The promise of his career as a rock singer had come to nothing. In the late 80s his multiracial funk rock band, the Dan Reed Network, had been hyped as the Next Big Thing in rock’n’roll. But now, eight years after the band had broken up, the days of performing in stadiums with the Rolling Stones were just a distant memory.

In Portland, Oregon, where he was born and had lived for much of his life, Reed retained a connection to the music business as co-owner of a nightclub called Key Largo. Rock bands would play in the evenings, before star DJs filled the club with rave music. Reed liked to mix with the rave crowd; he also loved the warm buzz he got from ecstasy. He’d pop a couple of pills each night, mixed with shots of Jägermeister and lines of cocaine. Most nights the party would continue after the club’s doors closed, upstairs in Reed’s private room, with a few friends, more drinks, more coke. But after a while it always seemed to end the same way, with Reed alone in that room for hours on end, out of his mind, and wondering whom he could call to score more drugs from at six in the morning.

There was a guitar in that room. He hadn’t played it in years. Although he had experimented in making electronic dance music, he couldn’t remember the last time he had written an orthodox song – a song with lyrics. But after he’d stared into the mirror that night and faced up to what he had become, he picked up the guitar. And it all came flowing out him: the music, just simple chords; the words, profound.

Reed had written so many great songs in the past. This one was unlike any other. He named it The Rush. What it amounted to was a confession. ‘Go climb your broken ladder to your lowest high/Go do your happy dance pretending you can fly/Go light a candle in the name of your last tear/The rush can be deadly… the rush is your only friend, your lonely friend…’

This was not the end of drugs for Dan Reed. The very next night he was back on the pipe, whacked out of his brain. But he knew he couldn’t go on like this. Writing that song would be the first step on a long road to redemption.

Dan Reed was 12 years old when he realised he could sing, and that this made him cooler than the other kids at his school. “I started impersonating Elvis,” he says. “Kids would pay me a dime to sing a song. I was like a human jukebox.”

It was 1975, and Reed was living with his mother and stepfather on a 200-acre farm in South Dakota. The nearest town was Chelsea. Its population was fewer than 70. “If you wanted to go to a movie or McDonald’s,” he says, “it was fifty miles away.”

Born on February 17, 1963, Dan had been raised in Portland by Elizabeth and her first husband, Edward Morris. When she remarried, to Thomas Reed in 1970, she took his surname, and so did Dan. In those early years in Portland, he was an unruly kid. “I was raising hell all the time,” he says. “Doing crazy shit.” What changed him was the calm authority of Thomas Reed. “He was such a decent man,” Dan says. “He straightened me out.”

This, he explains, was instrumental in how he dealt with the turmoil he experienced at the age of 14. “I didn’t know I was adopted till then,” he says. “I didn’t look like my mom, but I never really questioned it much. But the kids in school were giving me a hard time. They’d say: ‘That’s not your real mom and dad.’ So I asked my mom about it.” He learned that his birth mother was just 19 when she gave him up for adoption, having separated from his father, a Filipino who was serving in the US military. Reed says now that he has since been reunited with his mother. He has never met his father. “My real dad doesn’t even know I exist.” he says, without a trace of bitterness.

By 14, Reed had become obsessed with music. Two years earlier he’d bought his first album – Stampede, by the Doobie Brothers – and attended his first concert when his mother took him to see Johnny Cash and June Carter in Minneapolis. He was also playing the trumpet. Then in 1978 he heard the debut album by Van Halen. And it changed everything. “I quit playing trumpet a week later,” he says, “and ordered a guitar from a Sears & Roebuck catalogue.”

Within a few weeks he had started writing songs and had formed his first band, Nightwing, with a bunch of school friends.

By the turn of the 80s, Reed was making regular trips to Minneapolis to see big rock shows – Van Halen, the Doobies, Ted Nugent – and to buy records, including the early albums by local hero and rising star Prince. Reed liked Prince’s androgynous image. “He wore ladies’ panties,” Reed says, laughing. “That was a culture shock for us farm boys from South Dakota.” Above all, he loved how Prince combined hard funk with a rock’n’roll attitude and edge. “I was always drawn to music with a groove, whether it was Aerosmith or James Brown.”

By 1982, Reed’s plan was set: he would create his own funky rock’n’roll band. One thing he knew for sure was that this wasn’t going to happen in a small farming community. And so, at 19, he quit college and left the family home, returning to Portland alone. There he hooked up with a friend from South Dakota, Daniel Pred, who played drums. They formed a band called NoBoy, while Reed also moonlighted as keyboard player in a new wave group, Nimble Darts. “The name was slang for nice tits,” he explains. While gigging around Portland with both bands, he filled a notebook with useful contacts: musicians, promoters, DJs. He called it the Dan Reed Network.

In 1984, Reed and Pred hooked up with Brion James, a shit-hot guitarist, and Melvin Brannon Jr, a bassist who could slap like funk master Bootsy Collins. With two black musicians alongside Reed and the Jewish-American Pred, the new group had an ethnic mix reminiscent of pioneering late-60s outfit Sly & The Family Stone. The music, however, was absolutely contemporary: a blend of funk, hard rock and pop, heavily influenced by the biggest-selling album in America in 1984, Prince’s Purple Rain. “We loved rock and we loved funk,” Reed says. “The natural progression was to mix the two.”

It was Pred’s suggestion to name the band the Dan Reed Network. They played their first gig in December 1984. Six months later they had an EP, Breathless, released on a small indie label. Their rainbow coalition was completed by Japanese-American keyboard player Blake Sakamoto. By 1986 they had the backing of some of the most powerful figures in the music business: their manager was heavyweight concert promoter Bill Graham and they were signed to Mercury Records by Derek Shulman, at a time when one of Shulman’s previous acquisitions, Bon Jovi, were achieving their major breakthrough with the album Slippery When Wet. And the producer of that album, Bruce Fairbairn, was enlisted for the Network’s debut for Mercury.

“Derek Shulman took me to a Bon Jovi show in New Jersey,” Reed recalls. “The whole audience was freaking out, and Derek said to me: ‘Are you ready for this? It’s going to happen to you.’ And at that moment I fully believed in it.”

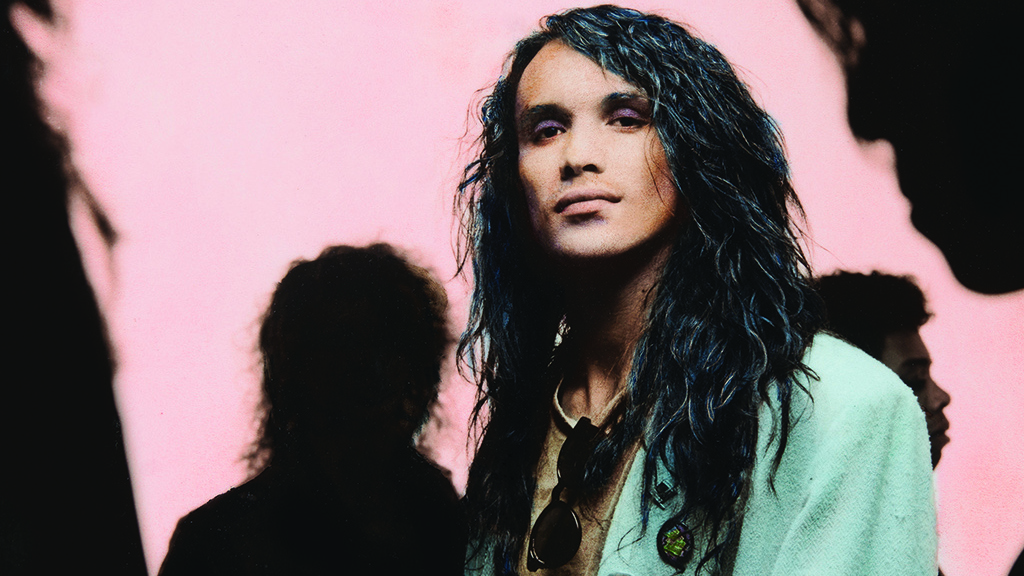

Reed and Shulman would not be alone in thinking that this band was destined to become one of the biggest in the world. When the debut album, Dan Reed Network, was released in 1987, there were other bands playing funk rock: Faith No More had arrived with Introduce Yourself; the Red Hot Chili Peppers were on their third album. Yet these were very much alternative rock bands, at a time when ‘alternative’ was still a byword for underground. Their music was gnarly. What the Network had was a sound built for radio and for arenas – described in Sounds as “Bon Jovi meets Prince”. And in Reed they had a frontman as good-looking as Jon Bon Jovi, with his long hair and high cheekbones – perfect for MTV.

Even when the Dan Reed Network album performed below expectations, peaking at No.95 in the US, Shulman and Mercury remained committed to breaking the band. For their second album, Slam, they had another big-name producer: Nile Rodgers, former leader of disco giants Chic, who had recently done hit records for Madonna, David Bowie and Duran Duran. They had new management in Q Prime, whose clients included Def Leppard and Metallica. And after Slam was released in 1989, the Dan Reed Network supported Bon Jovi on an arena tour.

Moreover, Slam was a brilliant album, with songs such as Tiger In A Dress, Stronger Than Steel and Rainbow Child that sounded like hits. But the Dan Reed Network couldn’t get on the radio – in America or anywhere else. “So many guys at radio told me the same thing,” Reed says. “They didn’t know where we fit. Too rock for R&B radio, too funky for the rock stations.”

As a result, the Network weren’t selling records. In the UK, Slam made it to No.66; in the US it stalled at No.160. Meanwhile, Faith No More and the Red Hot Chili Peppers were selling millions.

In the summer of 1990, the Dan Reed Network’s career hung in the balance. They had another huge tour, opening for the Rolling Stones in stadiums throughout Europe, and Mercury had picked Rainbow Child as a single. It was the best song on Slam, with a beautiful melody and a 60s-inspired hippie vibe. The consensus among those connected to the band was that this song could be the breakthrough hit. But when they came to shoot the video for the song in San Francisco, Reed did the strangest thing. “On the day of filming,” he says, “I woke at six in the morning and decided to shave my head.”

The idea had come from reading the autobiography of India’s former leader Mahatma Gandhi. “Gandhi had said that a monk keeps his hair close to the skin to remain humble,” Reed explains. “And humility was everything I needed at the time.” What Reed also admits now is that the pressure had got to him. “I felt trapped in this image I had.” By shaving his head he felt liberated. But in an era when long hair was de rigueur for rock stars, this spur-of-the-moment decision bordered on career suicide.

This much was spelt out to Reed in a phone call from Q Prime’s Peter Mensch, two hours before the video shoot. “Mensch tore me a new asshole,” Reed says. “He was yelling at me. ‘You’ve totally fucked everything up! Are you fucking insane?’ I said: ‘I may be, but I feel better than I’ve ever felt in my life.’ He told me: ‘You better put something on your head. We’re not having you bald in this video.’ So I ended up wearing this headdress.”

On the Stones tour the Network played to huge audiences, but Rainbow Child was not a hit. In addition, Reed’s new image led to widespread conjecture. “It was weird,” he says. “I went from being the pretty boy to the opposite extreme. I had people feeling sorry for me. Some thought I was sick. ‘Oh, he has cancer.’ ‘He has Aids.’ Other people thought that I’d lost my mind.”

He hadn’t lost his mind. That would come later. What had been lost, with the failure of Slam, was his band’s best chance at making it big.

Their third album, The Heat, was released in 1991. It included some great songs: The Salt Of Joy was Reed’s Purple Rain. Reed had also grown his hair back, albeit cut short. But in ’91, grunge was the new thing in rock’n’roll, and The Heat got lost in the shuffle. “The grunge scene flipped the whole music business on its side,” Reed says. “I loved a lot of those bands – Soundgarden, Alice In Chains – but I saw that we weren’t anywhere near that.”

Reed was already thinking about splitting the band when, in 1992, he spoke to an influential friend, Bob Guccione Jr, the publisher of US rock magazine Spin. It was, Reed says, one of those existential conversations. They talked about music as a force for social change; what Bob Geldof had achieved with Live Aid; how Reed had always seen his band as a symbol for unity. But as he told Guccione: “It’s people like the Dalai Lama who are really changing the world – using compassion as a weapon instead of war.” For Reed, the Dalai Lama’s teachings were as powerful as they were profound. “His constant example that joy is attainable even against a wall of negativity that hits us daily was just as powerful as the decisions that politicians make – if not more so.”

At the end of their conversation, Guccione made Reed an offer: “Get an interview with the Dalai Lama,” he said, “and I’ll put him on the cover of Spin.”

Reed made an approach via the Tibetan government. To his astonishment, his request for an interview was granted. He travelled to Dharamsala in Northern India, where the Dalai Lama was living in exile. “I spent two hours talking to His Holiness,” Reed says. “I came back from that trip with a completely different perspective,” Reed says. “I just felt that what I was doing for a living really didn’t have much purpose.”

On a more pragmatic level, Reed knew than the Network had run its course. “We’d been together so long,” he says. “And it just wasn’t working any more. It didn’t feel a family.” In 1993, the band broke up.

The great irony in Dan Reed’s story is that what he experienced in 1992, meeting one of the world’s great spiritual leaders, was followed by a descent into the soul‑destroying madness of drug addiction.

After disbanding the Network, he briefly joined another group, Adrenalin Sky, which under its previous name of Maggie’s Dream had been fronted by Lenny Kravitz. Reed attempted to break into the film business: acting, writing screenplays. He landed the lead role in a low-budget thriller called Zigzag, released in 1997. But he wasn’t making any money. With the offer of joint ownership of the Key Largo club in Portland came the promise of a fresh start. The club had sentimental value to Reed, as it was where the Network played many early gigs. He invested $40,000, all the money he had left from his music career.

Several years earlier, his parents had sold the farm in South Dakota and moved back to Portland. His father was now in his 90s and in poor health. Reed lived at their house, but was rarely home, spending all of his time at the club. He had never been the wildest of rock stars. “I screwed around,” he says. “But I’d never been a drinker, and never done cocaine, only pot.” At Key Largo he had no inhibitions. “It was crazy. Sometimes a bunch of us would do a little crystal meth and some liquid acid – you lick it from the palm of your hand – and then we’d go out in the woods and just go fucking nuts. Those were good times.”

The bad times began after Reed’s nose became so sore from snorting cocaine that he took to smoking crack instead. None of his drug buddies at the club would touch the stuff. Crack was considered a dirty drug: highly addictive and ruinous. It was something Reed did in isolation, his dirtiest secret. “I was a crackhead but working every day,” he says. “The first three months of doing crack, I loved it. Then I started getting paranoid.”

Reed says now that his parents must have known what he was doing, but it was never mentioned. “My mother would say: ‘Are you okay? Do you want some food?’ I was super-thin. I didn’t look anything like my real self. You just don’t know it when you’re doing it.” Reed knew on the night he wrote The Rush that he had to get clean. Ultimately, what brought him to his senses was the news that his mother broke to him one day at their home, that his father had been diagnosed with cancer. “In that moment,” he says, “I realised that I was not the man my father raised me to be.”

For three months, Reed spent his days caring for his father. “I was shaving his face and helping him get to the bathroom, putting diapers on him. You could see him decaying slowly.”

Each night, Reed would return to the club, attending to business before retreating to that little room to numb himself with booze, pills and coke.

In February 2003, Thomas Reed died at the age of 94. On the night he died, Dan Reed did drugs for the last time.

A week later he drove back to South Dakota to spread his father’s ashes on the farm. On his return to Portland, he sold his shares in the club, recouped his investment and gave half of the money to his mother. “Then,” he says, “I had to figure out what I was going to do with my life.”

It was a year after his father’s death that Reed decided he should get back to making music. “The way it happened,” he says, “was kind of funny.”

At that point he wasn’t thinking in terms of a career. On the contrary, he had returned to Dharamsala to study Buddhism at a monastery. He learned from the monks how to meditate. In exchange he taught them the words to a Western pop song they had heard: Queen’s We Will Rock You. He also had an acoustic guitar with him. He’d written more than 20 songs since The Rush, and while at the monastery he wrote another, On Your Side. “Two of the monks asked me to sing that song for them,” Reed says. “Afterwards they told me: ‘You should play music.’ When they said that, it just felt right.”

Even so, it was a long time before Reed was back in public view. He lived for two years in Israel, where he built a recording studio and made demos. In 2008, after relocating to Paris, he started playing low-key one-man shows around Europe. His comeback was eventually completed in 2010 with the release of his debut solo album, significantly titled Coming Up For Air. In the same year he moved again, to Prague, and promptly fell in love with Katka Blahova, the real estate agent who found an apartment for him in the city. And in 2012, there were two key events in his life – things that he never dreamed were possible 10 years previously. He and Katka had a son, his first child, named Joshua Thomas Reed in memory of Dan’s father. “He’s such a happy kid,” Reed says. “That makes me very proud.”

And on New Year’s Eve 2012, the Dan Reed Network reunited for a gig in Portland.

Since then the band have played a number of shows in Europe, including an appearance at the Download festival in 2014. Reed has also made two more solo records: Signal Fire and Transmission. And now, 25 years after The Heat, a new Dan Reed Network album, Fight Another Day, is imminent. The band includes four members of the classic line-up. Only Blake Sakamoto is missing, replaced by new keyboard player Rob Daiker.

“Making a new record with the band felt so good,” Reed says. “I never thought it would happen again. My solo stuff is my feminine side, the Network is more about male energy. And to exercise those muscles again at the age of fifty-three, it feels great.”

Fight Another Day is true to the style of the band’s previous albums – what Reed describes simply as “a mixture of rock, funk and electronic music” – but with a fresh, modern sound. And on the deepest level, it represents what Reed thought he had lost in his darkest days. “This,” he says, “is music that celebrates life.”

FUNK BROTHERS

Dan Reed wasn’t the only one mixing hard rock and funk in the late 80s.

Extreme

The shtick: If Aerosmith were the Bad Boys From Boston, Extreme were the Nice Boys.

How funky were they? As Queen fans, they knew where Freddie Mercury was coming from on Hot Space.

Key track: Get The Funk Out

Electric Boys

The shtick: The Stockholm Boys nailed their colours to the mast with the title of their 1989 debut album, Funk-O-Metal Carpet Ride.

How funky were they? For white guys, pretty fly – and they mixed it with a side of psychedelia.

Key track: All Lips ’N’ Hips

Stevie Salas Colorcode

The shtick: Native American guitar hero Stevie Salas launched his Hendrix-inspired power trio in 1990, and went on to play for Mick Jagger on the Stone’s solo tour.

How funky were they? Salas had the chops, but he was more Steve Stevens than Prince.

Key track: The Harder They Come

Bang Tango

The shtick: An LA hair band that looked like they were auditioning for The Cult and sounded like GN’R jamming with the Chili Peppers, while drunk.

How funky were they? What groove they had was a little hamstrung by singer Joe Lesté’s nails-on-a-blackboard screech.

Key track: Attack Of Life

Kingofthehill

The shtick: They came from unfashionable St. Louis, but sounded like a Sunset Strip band – and looked like one too.

How funky were they? Their self-titled debut album was like a funky Poison – in 1991, a bad career move.

Key track: I Do U