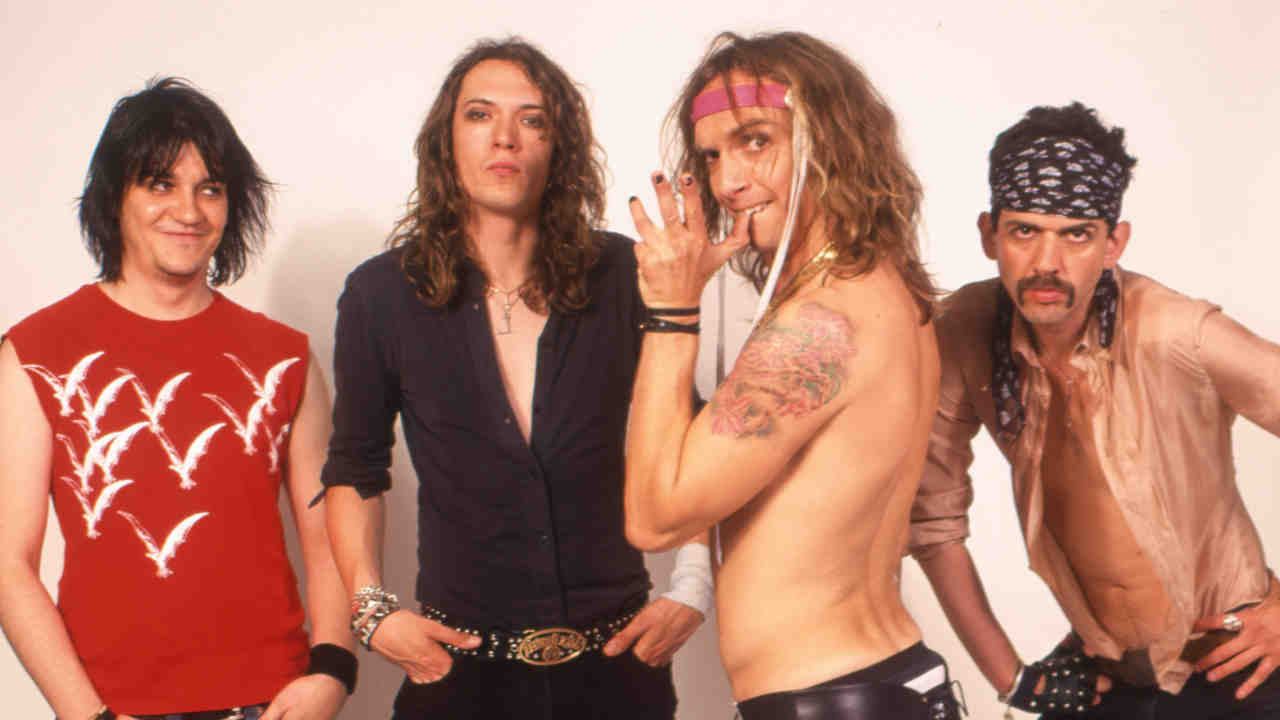

Thanks to the success of their debut album, 2003’s Permission To Land, The Darkness were one of the most unlikely success stories of the early 2000s – and one of the most divisive. In 2013, frontman Justin Hawkins, guitarist Dan Hawkins, bassist Frankie Poullain and original drummer Ed Graham looked back on their dizzying rise and the insanity that came with it.

Ask the members of The Darkness to pick one memory which defines that crazy period in the early 2000s when they went from hopelessly unfashionable no-marks to unlikely superstars in what seemed like 10 seconds flat, and their answer is unexpected.

It isn’t the moment when they heard that their debut album, 2003’s Permission To Land, had gone to No.1 in the UK. Nor is it the wealth and excesses that subsequently came with it. It’s not the time they picked up three Brit awards on one night. And it’s certainly not the ill-fated headline slot at the 2004 Reading Festival that effectively closed the curtain on their imperial period.

No, the thing that truly sticks in the mind of The Darkness is the very first time Justin Hawkins pulled on his catsuit, for a gig in the back room of the Castle pub in Tooting Bec, South London, on November 16, 2001.

“The catsuit was something I wanted to bring into it,” says Justin now. “My mother used to hang around with Brian Jones, and she once described an outfit he was wearing as being a pink catsuit seductively unzipped to a dangerously low area. She’d always reminisce fondly about that. So from childhood I always thought that the catsuit was part of the rock’n’roll theme.”

The rest of the band were less keen on this sartorial extravagance. “I remember having a pint with Dan [Hawkins, guitarist and younger brother of Justin] after the suit had become a regular fixture,” says drummer Ed Graham. “We were going: ‘You text him about it!’ ‘No, you text him about it!’ We both ended up texting him to say: ‘We’re not sure about these catsuits.’ His response was: ‘Fuck you, x [kiss].’”

It was an early example of both the shameless flamboyance and the bloody-minded stubbornness that would define the band in general, and their frontman in particular. Although in the case of Justin’s debut appearance in a catsuit, things didn’t exactly pan out as hoped.

“He wanted a white one but they got the material completely wrong,” laughs Dan Hawkins. “And as soon as he started sweating, it turned into a naked suit, a bit like Shakira. He had jeans on, and he started taking them off for the big reveal and realised he’d left his shoes on, and he was literally on his back while the song started. We were trying to keep it going while he was on the floor. Someone in the audience managed to prise the jeans off for him. A total fucking shambles.”

Little did the people in the audience realise what the future held for the man wriggling around on stage as his dignity took to the hills. Though it’s fair to say that half of them wouldn’t have lost sleep if they’d never seen the band again.

“That was a defining moment,” says bassist Frankie Poullain. “Some people thought we were really sad because we were playing a pub and thinking we were 70s rock stars, but then other people were coming up to say they hadn’t seen anything that entertaining in years. We divided people right from the start.”

For a year or so in the early 2000s, The Darkness were the biggest band in Britain. Permission To Land had crested the charts on its release in July 2003, a gloriously anomalous splash of colour amid the grim monochrome wasteland of the early-2000s music scene. Making no secret of their love of AC/DC, Thin Lizzy and Queen, they weren’t rock’n’roll’s future so much as a souped-up, tongue-in-cheek reboot of its past. More importantly, they brought back something that had long been missing in music: fun.

The Hawkins brothers had left their home town, the sleepy seaside enclave of Lowestoft, six years earlier. While Justin headed off to Huddersfield University, 16-year-old Dan opted to forego higher education entirely and decamped to London, where he formed a band, Empire, with French-born, Scottish-raised bassist Poullain. They were eventually joined on guitar and keyboards by Justin.

“We had a good singer, but he wasn’t right for us,” explains Dan. “At that time we were quite progressive. We’d just got into ridiculous time signatures, that I don’t think anyone could have sung on.”

Going nowhere slowly, Empire decided to call it quits. Dan became a session player, Frankie went off to become a tour guide in Venezuela, and Justin carved out a small niche for himself writing music for films and adverts (the nagging ditty for Ikea’s The Shlomp campaign was his).

Fortuitously, the brothers both returned home for Millennium Eve. It was while in Lowestoft that Justin entered a karaoke competition, performing Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody. He astounded his brother not only by successfully aping all of Freddie Mercury’s vocals, but also by throwing in several star jumps for good measure. That’s when Dan realised the man he was after was right under his nose. “I knew he could be the band’s singer then,” says Dan, “so I gave up trying to work with good musicians and scrabbled together a band with my brother and my best mates.”

Poullain gave up his job as a tour guide and returned to London, and they persuaded Ed Graham, an old school friend, to ditch his current band and play drums for the band they’d just christened The Darkness. But they still had an awful lot of work to do. At the turn of the decade, record labels were still trying to milk the Britpop scene, despite the fact it had long since curdled. Camden in North London had been Ground Zero during the heady days of the 90s, and A&R men continued to flock there in the hope of finding some of the old magic still hanging in the air.

So did The Darkness. In August 2000 they bagged an unofficial Saturday night residency at the Monarch, a pub-cum-venue opposite Camden Market. They would open the show for whoever was playing that night, taking the stage at 8.30pm sharp. The following April they graduated to a midweek slot, but their regular monthly Saturday night gig would be a mainstay for the band for the best part of two years.

“In the past we’ve said we wanted to do those Saturday night shows because we didn’t want to play in front of the industry, as they only came out in the week, and that we wanted to build a fan base,” says Dan. “The truth is that we played those slots because no one else would book us. But it worked for us. It wasn’t long before we were filling it out.”

Many of the songs that would end up on Permission To Land were already fully formed. I Believe In A Thing Called Love and arch power ballad Love Is Only A Feeling were featured in the set as early as their fifth gig. “In that earliest period we wrote some of our strongest songs,” says Justin. “We started working out who we were early on.”

That was more than could be said for the record labels. The band’s unapologetically retro influences were out of step with prevailing trends, while their frontman’s outrageous posturing – part Freddie Mercury, part Angus Young, part Catwoman – put as many people off as it drew in.

“We did have lots of A&R men walking out and being reprimanded by senior A&R guys,” says Poullain. “They’d literally be led out of the venue after we’d done a couple of songs, almost as if we’d played an April Fool’s joke on them.”

If the band were going to succeed, they had to make it happen themselves. Their debut EP, I Believe In A Thing Called Love, got the attention of sections of the music press when it was released in 2002 on the tiny independent label, Must Destroy!. The media attention in turn made the labels think again.

“I think we had to go to a certain level ourselves before they’d jump on board, and then everyone tried to jump on board,” says Dan.

By the spring of 2003 The Darkness had been picked up by Atlantic Records. That April they sold out the 2,000-capacity Astoria in London.

“We had this tiny bank of lights either side of the stage, which we made sure were the same colour as Queen’s,” says Dan. “The DJ from the night before had left some of his tables out and we made a riser out of them, but it was all gaffa‑taped together and wobbling like fuck. It could have gone horribly wrong. What a way to go though.”

Happily, all four members of the band made it through the gigs with limbs, and dignity, intact. Suddenly this most unfashionable of bands was in serious danger of becoming trendy.

For all their frontman’s peacocking, The Darkness had a reliably British earthiness to them. Fittingly, Permission To Land was made on the sort of budget that would barely cover the catering bill on many bigger records.

“It was all done fairly cheaply,” says Dan. “The producer, Pedro Ferreira, was my best friend, and we had our own production room, which was part of a studio in Willesden in North London. The good thing was that we could go into the main studio when it wasn’t being used.”

Unlike many bands on their first album, The Darkness eschewed the ‘in and out’ ethos, preferring to pore over their songs, piling on layers of guitars and vocals that would have done Freddie Mercury proud. But the approach had its downside. “We took so long that we ran out of money,” says Dan. “After six months we only had four or five songs done. It had all gone a bit Def Leppard.”

Scrabbling together a budget to record the rest of the songs, they relocated to Chapel Studios in Lincolnshire, where they finished off the record in seven days with the help of a sleep-deprived Pedro Ferreira. “That’s why some of it is really raw in some places and then over-produced in other places,” says Dan. “But I think we nailed it.”

By the time the record was released in July 2003, The Darkness had plenty of wind in their sails. Previous single Get Your Hands Off My Woman had given them their first Top 20 hit, and the band were building a reputation as one of the best live acts around. Even so, no one anticipated just how well the album would do – it entered the UK chart at No.2, and climbed to the No.1 within a few weeks.

With hindsight, the fact that The Darkness were so outlandish counted in their favour. Record companies were hedging their bets by signing Coldplay clones and Dido soundalikes, while nu metal had given way to the middle-of-the-road stylings of Linkin Park and Evanescence. Only a new wave of garage rock spearheaded by The Strokes and the White Stripes provided a glimmer of excitement. No one was performing star jumps, let alone rocking a catsuit.

“It was all so dull during that period, musically,” says Ed Graham. “We were an antidote to what was happening. When we supported Robbie Williams at Knebworth [on August 1-3, 2003], that’s the thing that put us in The Sun and helped us cross over. We each had a look, and there were all these girlies who had their favourite Darkness member. Obviously, my appeal was more selective.”

But not everyone embraced them. Justin Hawkins’s shriek and OTT stage antics polarised opinion like few other frontmen. The band were even viewed with suspicion by a large section of the heartland rock audience, who saw them as some sort of elaborate conceptual joke.

“It made people nervous that we were smiling and enjoying what we were doing,” says Dan. “People get uncomfortable around that. It’s as if you’re not taking it seriously, so why should they?”

“James Dean Bradfield once said we were a vaudeville band,” adds Poullain. “I thought that was quite astute. What was it Adam Ant said? ‘Ridicule is nothing to be scared of…’ And a lot of people are scared of being ridiculed. We weren’t.”

Though the band were now proper pop stars, they were still skint. When they’d supported Def Leppard at London’s Brixton Academy earlier in the year, a broke Dan Hawkins had to take three buses to get to the gig. Even then he’d had to walk the last bit of the journey. “We had a meeting with management after the album had charted, and said: ‘Is there any way we can avoid public transport? It’s starting to get a bit embarrassing. That’s when we were finally put on a wage.”

Their ship truly came in at the end of that year, when Permission To Land was well on its way to selling an eventual 1.5 million copies in the UK alone. The band went from worrying that they couldn’t afford to eat, to being able to afford to buy a house.

“I went to a cashpoint and I thought I had about ten quid left,” says Dan. “I saw something that looked like 100 there instead. I thought, God, I’m overdrawn again. Then I looked at it and saw it was 100 and a few noughts after it, and that I was in credit. It was Christmas, so the first thing I did was buy the most expensive sledge I could find for one of my friends who’d just had a kid, and went straight round his house and said: ‘Merry Christmas’. That was wild.”

Things would get a lot wilder than spontaneously purchased festive presents. As the band’s success grew, so did their consumption of booze and, in the case of certain members, other substances. Asked now if there was a specific point when the wheels came off the wagon, Dan Hawkins laughs.

“The wheels were never on,” he says. “It was always carnage. We partied on the road all the time, then I’d get home and see my friends and start the party all over again. It got to the point where I thought, “If this carries on, I might die.’ That’s when I left London and moved to the countryside.”

But amid the booze and drug-fuelled chaos, there was still work to do. With an unexpected No.1 album in the UK, Atlantic were keen to push the band Stateside. America, the label reasoned, would embrace The Darkness’s classic rock’n’roll stylings, if not their flamboyance. And so it proved – at least initially.

“The first time we went to America we couldn’t get out of the car without being recognised,” says Justin. “At one point they said it was the biggest-selling debut album in America since the Spice Girls, which is a lovely statistic – I want that on my headstone. But we were just touring and touring, and we ended up going back there with no second hit single to play to the same people, when it would have been nice to stop and concentrate on where we were heading next.”

In August 2004 The Darkness brought the Permission To Land campaign to a close with a headlining appearance at the Reading Festival. It was an under-par performance by their standards – the band looked lost on a big stage, they padded out the set with unfamiliar new songs, and even Justin seemed to have left his confidence in the backstage Winnebago. In retrospect it was the point at which things began to turn for The Darkness – their crueller critics suggested that the emperor had been found stark bollock naked in the street.

The problems at their heart truly manifested themselves on their second album, One Way Ticket To Hell… And Back. Recorded at great expense with Queen producer Roy Thomas Baker, it found the band tearing themselves apart at the seams.

“Certain narcotic-based elements exacerbated present tensions,” says Justin. “All of us changed in an unpleasant way. It was only a matter of time before we stopped communicating entirely.”

Frankie Poullain was the first victim of these tensions. The bassist was fired halfway through the sessions, and replaced by roadie Richie Edwards.

“I think I was quite abrasive,” says the bassist now. “I guess it was my job to be the one who questioned things, and I got carried away with it. There was the drinking, some of us were on the powder, some of us were just hopping from bed to bed… I guess you grow apart, don’t you?”

Ed Graham calls One Way Ticket… “the million-dollar failure”. It lacks the charm of its predecessor, and its overblown excesses certainly sound like the work of a band on a lot of cocaine, but it wasn’t the musical disaster it has been painted as. Commercially it was a different matter. Released in November 2005, it failed to dent the Top 10.

There was worse was to come. In September 2006 The Sun announced that Justin Hawkins had completed a three-month stint in rehab and was leaving The Darkness. The brief but glorious burst of fun was over.

Today, the success of Permission To Land feels like a strange dream. Not only did it turn a gloriously OTT band from Lowestoft into A-list superstars, it did so at a time when the sort of music they were playing couldn’t have been less cool. It also feels like the last time a rock band properly made an impact on the wider world. You couldn’t imagine it happening now – more’s the pity.

The Darkness reunited in 2011 after a six-year hiatus in which their respective solo projects (Dan and Ed’s Stone Gods, Justin’s Hot Leg) failed to set the world alight.

The band’s most recent album, last year’s Hot Cakes, was a fine comeback effort, even if the band were aware that it could never replicate the freakish success of their debut. “Permission still has that zeal and energy of a gang,” says Dan. “And we stopped being that gang. So it’s no wonder the records never sounded the same after that.”

“I think,” adds Justin, “if you want to be interested in what you’re doing, you have to realise how precious it is. I don’t mean the success, I mean the art of it. Because that’s what’s enjoyable – the process of it. These four men, who have nothing in common, really kicking ass together. It’s a hilarious experience.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 191, November 2013

![The Darkness - Get Your Hands Off My Woman (Official Music Video) [HD] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/hI9eVW4cTR8/maxresdefault.jpg)

![The Darkness - I Believe In A Thing Called Love (Official Music Video) [HD] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/tKjZuykKY1I/maxresdefault.jpg)

![The Darkness - Growing On Me [Live at Knebworth 2003] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/t7oOlqD3VGY/maxresdefault.jpg)