As a founder member of the Strawberry Hill Boys, Dave Cousins helped move the band through bluegrass and folk until they finally became international prog icons Strawbs, who could count Led Zeppelin among their fans. In 2019 Cousins told Prog about his journey from underground band to the household name that helped give Sandy Denny and Rick Wakeman their breaks.

Having notched up 19 studio albums since Strawbs’ 1969 self-titled debut, Dave Cousins has remained the one constant at the centre of the band, amid various shifts in musical directions and sometimes turbulent personnel changes. And the prolific songwriter and vocalist intends to stay busy. “While I still enjoy it, I’ll keep on doing it,” he says.

In 2019 Strawbs celebrated their golden jubilee at a gala event in Lakewood, New Jersey. Backed by a 30-piece orchestra and a choir of staff members from New York’s United Nations building, the gig covered their lengthy career from start to present day. Cousins recalls: “Tony Visconti, who’d worked with us on our very first records, agreed to come and conduct.

“It was unbelievable to have Tony there. We did our very first single, Oh, How She Changed, with Dave Lambert singing, backed by the orchestra. We also had the choir sing an amazing rendition of Lay Down and they accompanied us on We Have The Power from our 2017 album, The Ferryman’s Curse. That was extraordinary.”

The three-day celebration featured many musicians who’ve played live or recorded with the band. “Strawbs are a family. You can never overlook that. And we all get on very well together. Even though people left the band there was never really any hard feeling. Yes, there might have been aggravation at the time – but by and large, we’ve all stuck together and looked after one another.”

Whether it’s touring on his own or with The Acoustic Strawbs alongside longtime members bassist Chas Cronk and guitarist Lambert, 2020 looks like another busy year. When Prog caught up with Cousins at his home in Kent, he was still at the early stages of working on Strawbs’ 20th studio album.

“At the moment I’ve got ideas and a few scraps of paper with titles on them. I’m going down to my local pub, who’ve agreed to let me have the back room on an afternoon, where I can sit on my own and get on with the writing.”

You started out playing the folk circuit in the early 1960s.

Yes – though we were never a folk group as such. I was the fastest banjo player around, Tony Hooper was the lead singer and we had a double bass player. Before that we’d done a BBC audition which we passed, and I started ringing up BBC producers trying to get us work. One of them returned our call and told us we were recording the next week. The show was broadcast in 1963 and we shared billing on Saturday Club with Chris Barber’s Jazz Band and The Beatles.

Captain Beefheart said, ‘I can’t do this interview without running water.’ He put the tap on. It sounded as if he was having a pee!

At the time, I was the cloakroom attendant at Eel Pie Island Jazz Club in Twickenham; Arthur Chisnall, who ran the club, heard us on the radio and asked if we’d like to do the intervals for a group he had coming in. They were booked for the next six weeks and they were called The Rolling Stones. No idea what happened to them!

A bit later you were a producer on a pop show for Danish radio. How did that happen?

Tom Browne, who was later a Radio 1 DJ, did an interview with me about the Strawberry Hill Boys and he helped set up a tour of Denmark. I got booked for a Danish TV show. Also on there was The Who, promoting I Can’t Explain, and I got chatting to them afterwards. Pete Townshend gave me his phone number and told me to give him a ring sometime.

Anyway, Tom Browne had been asked by Danish radio to do a pop show from London called The London News. He said to me, ‘I know nothing about pop music – will you produce it?’ He and I interviewed all sorts of people: David Bowie, Sandy Shaw, Marc Bolan, Mary Hopkin, Keith Emerson.

We even interviewed Captain Beefheart on his first visit to England. We went up to his hotel off Oxford Street and he said, ‘I can’t do this interview without running water.’ So he went into the toilet, put the tap on, came back in and then we talked. Of course, when we came to edit, it sounded as if he was having a pee throughout the interview!

How did you meet Sandy Denny?

I’d gone to The Troubadour in Earl’s Court, and there’s Sandy down there wearing a long white dress and a straw hat playing a Gibson Hummingbird, singing the Gaelic song Fear a’ Bhàta. I introduced myself after she came offstage and asked if she wanted to join my group. ‘What’s the name?’ she asked. ‘Strawbs,’ I told her, and she said, ‘Yeah, okay.’ It was as simple as that!

“It was in 1967. She was 20 at the time and living at home with her mum and dad. She joined us and we were booked to play in Denmark. We really got to know Sandy on the ferry from Newcastle to Aarhus where we sat up all night, rehearsing and drinking every bottle of beer that was on the ship.

Sandy joined Fairport Convention – which I didn’t mind. We were still the best of friends. She was an absolute icon

We got signed to Sonet Records, run by Karl-Emil Knudsen, and made a record in Copenhagen in an old cinema. We could only record during the day because people had to be let into see the film in the evening. So we’d go off and play in Tivoli Gardens with Sandy singing.

It was the only time we performed on stage with her, really. She came back to England and, after three months, I hadn’t been able to get anybody in England interested in releasing it. By then Sandy had joined Fairport Convention – which I didn’t mind. We were still the best of friends. She was an absolute icon.

And you were the first British act to sign to A&M Records, weren’t you?

Yes. That was through Knudsen, who distributed A&M in Denmark. He played them the recordings with Sandy; and although they were disappointed she wasn’t with us anymore, Jerry Moss – the M of A&M – phoned to tell me they were excited to have us and wanted a single. We were in the studio with Gus Dudgeon as producer, who shared his office with Tony Visconti.

A&M had sent $15,000, which at that time was a colossal amount of money, and it was all spent on that first record because Gus Dugeon wanted to prove himself with orchestras and Christ knows what. So when they said they wanted another album we asked for more money. They told us the cash they’d originally sent was to be spread across three albums!

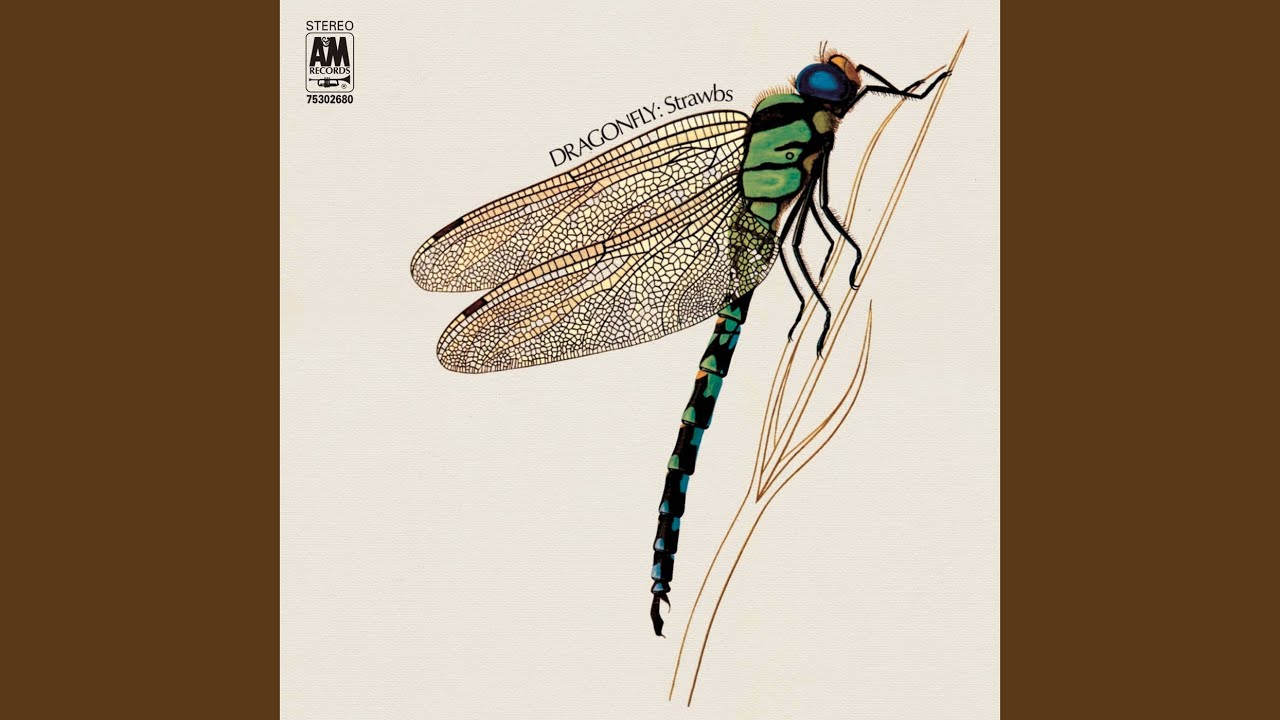

So we went from London back to Denmark, but we took Tony Visconti with us because Gus had buried my voice on the first album. So Tony produced Dragonfly [1970].

How did you hook up with Rick Wakeman?

We’d been asked to do a session for the John Peel show and we wanted to do a piece called The Battle, but we didn’t have a keyboard player. Tony suggested he bring Rick along, and it was great – we got on famously. When it came to Dragonfly we had him play on The Vision Of The Lady Of The Lake.

I asked Rick where he was going for the honeymoon. He said, ‘We can’t afford one’ … So he came to Paris with us and had his honeymoon there

I put his name on the sleeve notes, and when it came out sent him a copy. He said he was thrilled – that was the first time he’d had his name on the back of an album.

We met up and had a beer and I asked him to join the group. Our first gig with him was to be in Paris a fortnight later, but he said, ‘I can’t do that; I’m getting married.’ I asked him where he was going for the honeymoon. He said, ‘We’re not; we can’t afford one.’ So I said, ‘Well, I’ve got an idea…’ He came to Paris with us and had his honeymoon there!

After Dragonfly your music shifted towards a more electric sound. Was that deliberate?

We’d been using acoustic bass but it just wasn’t working for what we needed. At the time I had a folk club and then an arts lab in Hounslow and I’d booked Elmer Gantry’s Velvet Opera. It had guitarist Paul Brett, who’d guested with us on Dragonfly; and Richard Hudson and John Ford on drums and bass respectively. I thought they were great and invited them to join.

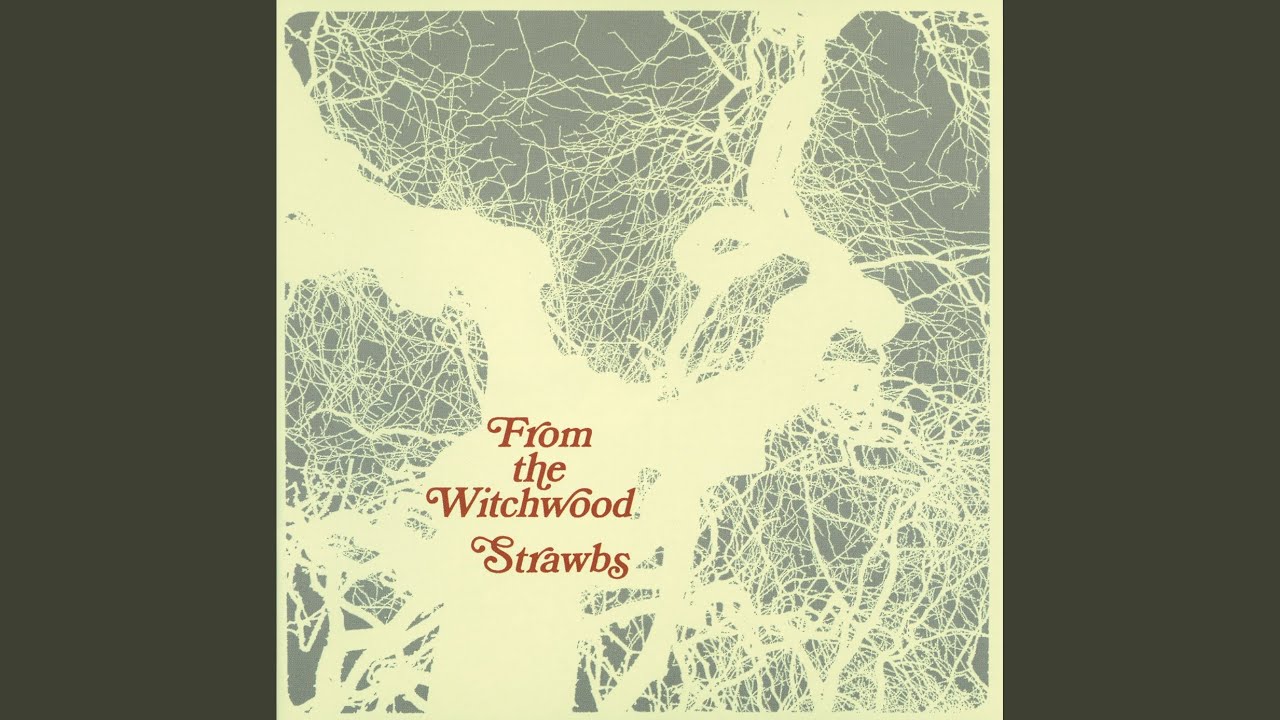

I still viewed us as a folk group, so the fact that Richard played percussion rather than a regular drum kit is what attracted me. It was only when we made From The Witchwood [1971] that we brought drums in for the first time, but they were very much mixed down because I didn’t want them to overwhelm the songs.

From The Witchwood has quite an eclectic mix of sounds and instruments, doesn’t it?

Yes, it does. On A Glimpse Of Heaven you’ve got multi-tracked voices to create a choir, Rick steaming in with a ferocious Hammond organ solo, and me playing bluegrass banjo behind him. Witchwood has me playing dulcimer and Rick playing clarinet – his second instrument at college. The Shepherd’s Song has that great Mellotron part as well as Rick’s great synth solo.

That was the first time we used a Mellotron. Also in the studio was a Moog synthesiser, the really big one. Rick sat with Tony and they got a sort of piccolo trumpet sound which Rick overdubbed. I’d been influenced on that song by Alone Again Or by Love. I adored that song and still do. So Rick dubbed that Moog on top of the strings.

We recorded a version of Part Of The Union that was far more left-wing, but that wasn’t released

You must have been really sorry to lose Rick to Yes.

Well, of course – but we’d been paying Rick £25 a week and Yes offered him £100, so it was understandable really. Funnily enough history repeated itself, because we had Oliver, Rick’s son, playing with us for a while, and he left us to join Yes as well!

1972’s Grave New World had a grander, more dramatic feel to it, and of course it had that fantastic triple fold-out sleeve which must have been very expensive to produce at the time.

The sleeve was immensely powerful. We’d become quite a significant band so A&M didn’t mind spending the money. We went from selling 5,000 copies of From The Witchwood to selling 98,000 in the UK with Grave New World.

A&M did the artwork and we had no involvement, other than me writing the sleeve notes and choosing the bits of text from the Egyptian Book Of The Dead and the Tibetan book of the dead [Bardo Thodol].

I had no idea what was going to go into the artwork until I saw the finished thing. I was staggered. The William Blake painting The Dance Of Albion [also known as Glad Day] is an immensely powerful picture as well. As for the middle picture, I’ve got that hanging on my wall at home.

You had an unexpected hit single in the UK with Part Of The Union, which got to No. 2 in 1973. Was that a blessing or a curse?

That song has been an albatross round our necks since it came out – in this country anyway. It was No. 1 in Germany because it’s an oom-pah song. In America nobody heard it. The first song we recorded for what became Bursting At The Seams was Lay Down and that was very much in my style.

At the same time, Hud and John had recorded a demo of Part Of The Union, and were going to put it out under the name of The Brothers. The publicity we got from the song at the time of the miners’ strikes and the three-day week and so on, was colossal.

But the problem was we didn’t come out and say whether we were left-wing or right-wing; we kind of sat on the fence. I think, unfortunately, that clouded the judgment of us for a few people. We recorded a version that was far more left-wing, but that wasn’t released. I have that on a cassette still.

The album title Bursting At The Seams was very apt. Things in the band had become quite acrimonious, hadn’t they?

Yeah. I was taken to one side by our manager, who said, ‘The band have decided to fire you. ‘We’re going to keep you on as a solo artist and they’re going to carry on as Strawbs.’ I said, ‘Over my dead body.’ There was a bloodbath in Hollywood, where we were at the time, and so John and Richard went their separate way and had some success as Hudson Ford.

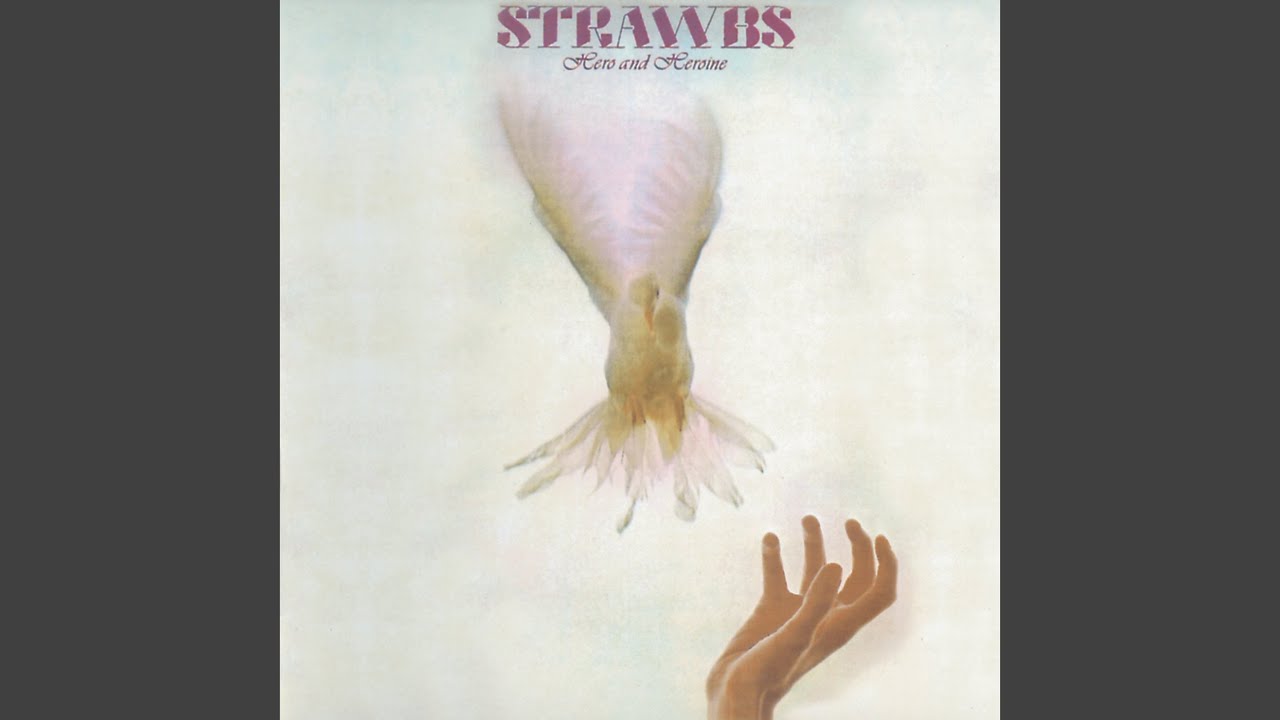

Your next album, 1973’s Hero And Heroine, is regarded as a classic, featuring John Hawken from the original Renaissance on keyboards.

When John came in he’d never touched a Mellotron or a synthesiser. ‘What do I do with this?’ he said. But he was such a useful piano player with such a wonderful touch. I’d first heard him on that first Renaissance album [1969] when I was producing my Danish radio show. Hero And Heroine was when we became a proper progressive rock band. It was probably our biggest album worldwide, especially in America.

The most satisfying shows we did at the time were the double-header shows with King Crimson. Both bands liked one another’s company. There was a sympathy between Hero And Heroine – tracks like The River and Down By The Sea – and King Crimson, who were doing a lot of Larks’ Tongues In Aspic at the time.

Led Zeppelin would fly out to wherever they were playing, come back on their private jet and watch our last set

Life on the road can take its toll in terms of relationships and personal health. How did you cope with it?

We weren’t into drugs. We loved a good old drink, you know? Yes, we occasionally smoked a few joints, but not coke or anything like that. It’s only when we met up with Led Zeppelin in Hollywood that I had coke with John Bonham, which was an extraordinary experience. He kept pushing my head down to the table, saying, ‘More, more, more!’

Our first gig in the States was a week-long residency at the Whiskey A Go Go. Zeppelin would go flying out to wherever they were playing that day, come back on their private jet to the Go Go and watch our last set. They did that two or three nights running. Our audience were astonished that Led Zeppelin were there watching us.

Your 1976 album, Deep Cuts, was given the deluxe reissue treatment last year. How you think it stands up?

It’s probably the best-sounding Strawbs album of the lot – but we were rushed into doing it. I didn’t have any songs. I’d just sold a cottage in Devon that I was about to move out of, so it had no furniture in it. I invited Chas Cronk to come down.

We went down the pub first and then went back, sat on the floor with two guitars, and in less than five days we’d written six or seven songs. It turned out to be more of a pop album due to the pressure of management saying we really needed a hit single.

Were you pleased by the reception for your 2017 album The Ferryman’s Curse?

Yes! It went into the prog rock album charts and I was thrilled. It wasn’t easy to make that album. I had a terrible hernia and it made singing a lot of the songs incredibly painful. I was also suffering from kidney problems; I was in and out of the hospital a lot of the time.

It was well-received by fans and critics so that was great. Some of the joy was taken from it, however, because our producer, Chris Tsangarides [Colosseum II, Brand X] sadly died a month later, which really broke my heart.

I asked Universal if they could get Steven Wilson to remix Hero And Heroine, but they weren’t keen

What’s the Strawbs album you would point to and say, ‘This is what you need to listen to?’

Grave New World. There’s one thing wrong with the studio version – we put it right in the live recording from our 50th anniversary show, which we’re going to release soon. We reprise Grave New World in a different key and suddenly the whole thing goes circular, comes to a resolution and makes sense.

Rolling Stone magazine listed Hero And Heroine as one of the 50 greatest prog rock albums of all time. Universal owns the masters of the biggest albums on A&M. When Steven Wilson started remixing all the classic albums by King Crimson, Yes and others, I wrote to Universal and asked them if they could get Steven to remix it to 5.1, but they weren’t keen on the idea.

Yet 50 years on our albums are still selling. We repaid our advance from A&M 20 years ago and we’ve been receiving royalties ever since. They’ve totally recouped. Now, for argument’s sake, say the royalty is 10 per cent and we’ve been paid over £100,000 – that means Universal has grossed a million pounds over the last 20 years. There aren’t many bands from that era still selling those kinds of quantities.