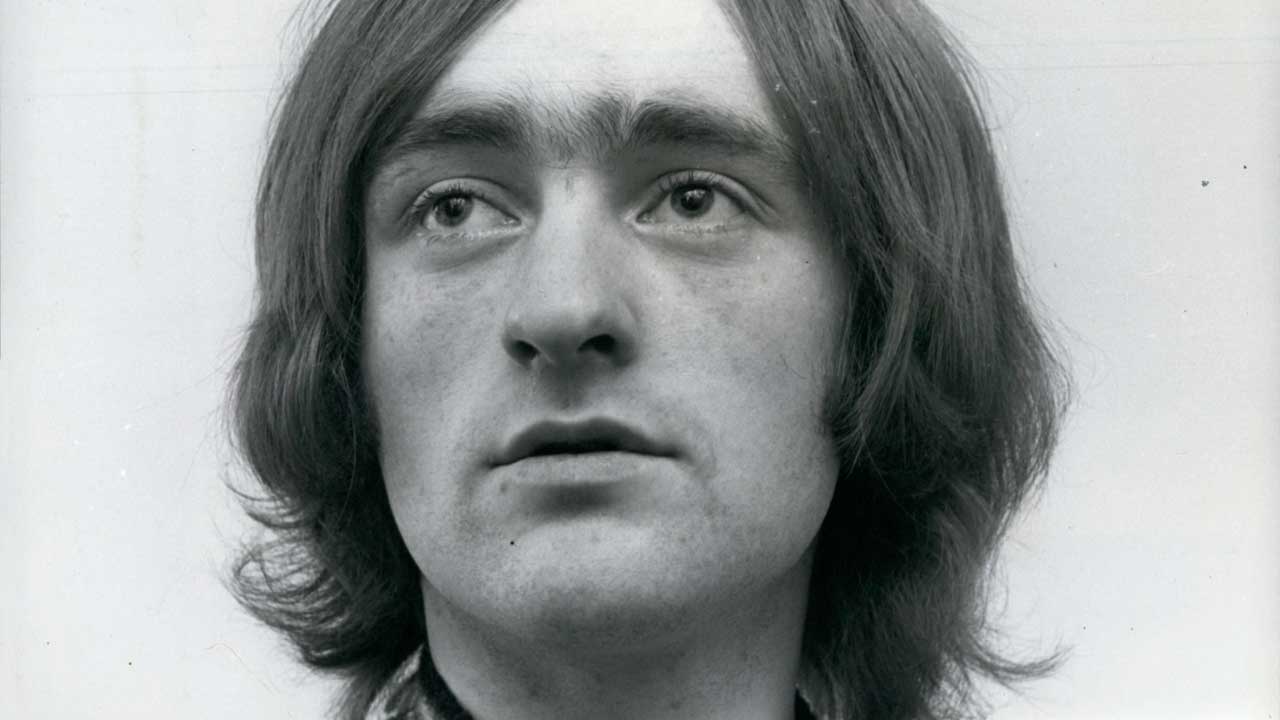

A real-life Mr Fantasy, Traffic guitarist Dave Mason wrote their biggest hit before leaving, only to return with a song that became even bigger. He introduced Jimi Hendrix to Bob Dylan's All Along The Watchtower – and played on his iconic cover version. He joined Derek And The Dominos for one show, was a member of Fleetwood Mac, and played on songs by George Harrison and the Rolling Stones. He even duetted with Michael Jackson. And in 2019, he told Classic Rock all about it.

Almost 51 years ago, Dave Mason was holed up with bandmates Steve Winwood, Jim Capaldi and Chris Wood at Olympic Studios in London. They were there recording their second album together as Traffic, the followup to their Mr. Fantasy debut of a year earlier on which they had crystallised the sound of Britain’s psychedelic-hued Summer of Love.

Guitarist Mason wrote that album’s big hit, Hole In My Shoe, which the others had come to deride, and soon he left the group. He had returned after a restorative sojourn on a Greek island, and brought with him to the studio Feelin’ Alright, which would become a hit and launch what would become the Traffic album. Mason’s signature song, it was also covered by Joe Cocker and American rockers Three Dog Night, but by then Traffic’s perennial odd man out had left the group again.

Today Mason is at his home on the Hawaiian island of Maui, where he is delighted to report that the midmorning sun is out and the sky a denim shade of blue. He headed to the US following his second, enforced, exit from Traffic, initially settled in Los Angeles and has resided in the States ever since. That much explains the peculiarities of his accent, a collision of Californian drawl and the sing-song vowels of his native English Midlands. He’s now seventy-two, but his easy laugh makes him sound decades younger, and he has packed a lot into his musical life.

Traffic began in the far-off spring of 1967, when Winwood jumped ship from the Spencer Davis Group – having made his name as a teenage prodigy-genius – and into a new, more expansive collaboration with three local musicians he had encountered over after-hours jam sessions at boho Birmingham club the Elbow Room. In short order, Traffic encouraged an exodus of English bands to ‘get it together in the country’ when the fourpiece moved into a tumbledown cottage in rural Berkshire and jammed Mr. Fantasy into being. They went on to establish themselves as sonic adventurers and virtuosos, their sound ranging from folk, prog and blues to jazz flourishes and Middle Eastern drones.

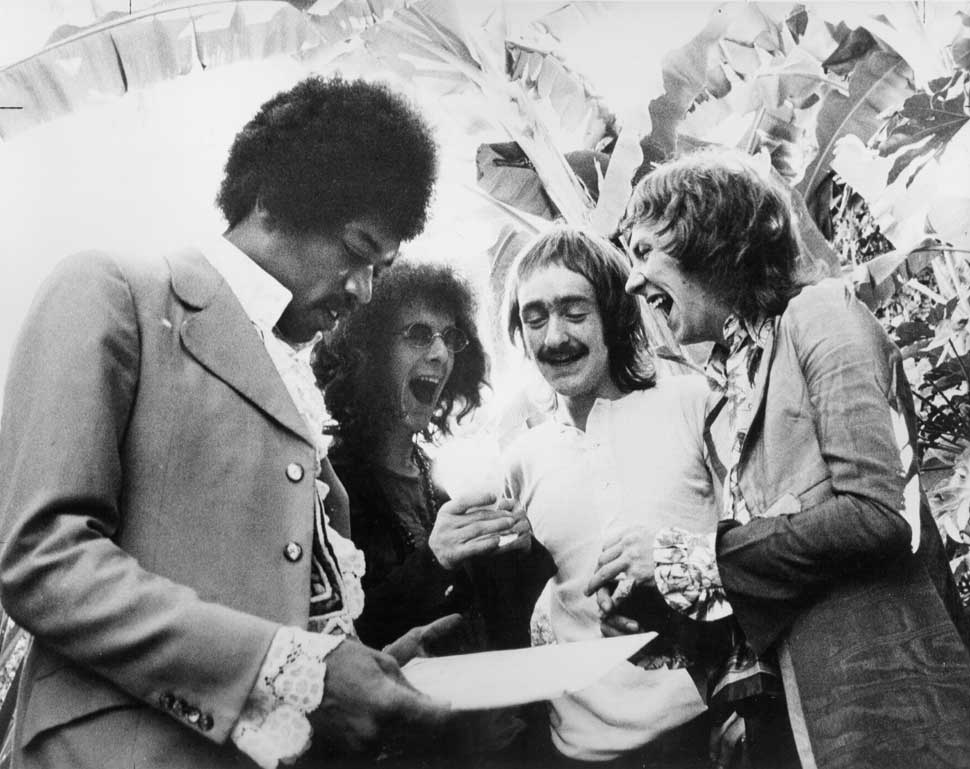

Mason returned briefly, for a third stint in Traffic in 1971. In between times, he introduced his friend Jimi Hendrix to Bob Dylan’s All Along the Watchtower and played on the coruscating version on Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland masterpiece, and guested on two more seminal albums of the period: the Rolling Stones’ Beggars Banquet and George Harrison’s sprawling post-Beatles bow All Things Must Pass.

At the Stones session, Mason met and befriended Gram Parsons, who subsequently courted him around the 70s LA rock elite. He toured with Delaney and Bonnie And Friends. Eric Clapton was among the other Friends, and afterwards invited Mason into Derek And The Dominos. A lone wolf, Mason stayed in that band for just one gig.

After that he threw himself into a solo career that has yielded 13 studio albums, which have variously featured contributions from Mama Cass, Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson and each of Crosby, Stills and Nash. In the 90s he did a couple of years of filling Lindsey Buckingham’s shoes in Fleetwood Mac, before going back out under his own name once more. Today he tours regularly with Dave Mason Band, racking up around 100 gigs a year.

“Making records these days to me is just an exercise in futility,” he says, his so-laid-back-its-horizontal speaking voice competing against the barking of his dog. “There’s no music business left and no record sales, and so sadly I don’t focus on that side of things any more.”

Growing up in Worcester in the 1950s, what first turned you on to music?

I was in the school choir, but for me it was the same as everybody else back then: Bill Haley and Rock Around The Clock, Buddy Holly, and the rest. Then I went to America when I was eleven to visit my sister. She was living in San Diego, and there was just so much more music – so much more of everything. Growing up in England back then we had one TV station, black and white.

From my early teens my dream had been to go into the RAF, but my maths skills weren’t up to par. Music and all these bands were just starting to happen for me, so I decided I’d rather play guitar. It was a wing and a prayer. Jim Capaldi lived just down the road from me in Evesham. Robert Plant was twelve miles away and Mick Ralphs was nearby too. Jim used to have a band called The Sapphires. He was the lead singer and very much an Elvis impersonator. The pair of us put a couple of incarnations of bands together, The Hellions being one of them. We played school dances and the pubs and clubs up in Birmingham, that kind of nonsense.

Obviously, we were fans of the Spencer Davis Group and this fifteen-year-old kid Winwood, but it was at the Elbow Room that we struck up a kind of musical admiration society. Chris Wood was an art student, and the four of us basically hung out, got high and listened to music. Eventually Steve got tired of being ‘the young Ray Charles’ with Spencer Davis, and that’s how Traffic developed.

Was the reality of the four members of Traffic living together at the cottage as idyllic as it sounds?

Yeah, it was great. We just wanted to isolate ourselves and figure things out, because we really didn’t know what the hell we were going to do with Traffic. Traffic was probably one of the original alternative bands. God knows, we were a jam band before that phrase even got coined.

I was the one who went: “Let’s start writing and see what we can come up with.” I had never written songs before. I was brought up in an upper-middle-class English family and had zero street smarts. Most of my early attempts, I look back and they’re a little trite and very naive. But the weird thing was, the first song I ever wrote was Hole In My Shoe, and that became Traffic’s biggest hit. Therein also lay the seeds of the break-up of the band.

Were you aware at the time quite how much the other three reviled that song?

That didn’t become apparent until after the second Traffic album. We were just trying anything and everything on that first album, it was the era of us all experimenting. Everything seemed possible at that age ,and we made it that way with how it was that we lived. I left after that first album not because of any aggravation at all with the band, I couldn’t deal with our success. The way people’s attitudes toward me changed was not normal for me.

Returning to the band with Feelin’ Alright must nevertheless have felt to you like a validation?

Again, with the second album all my stuff was picked out as singles, and that became the straw that broke the camel’s back. Steve later gave a quote that I was nothing more in the band than an uninvited guest. See, I always looked at Traffic as it being our differences that together made us great, but it just wasn’t going to go that way. The three of them made it pretty clear that I didn’t fit any more in a band that I had started. Jim and I even came up with the name.

It’s just very odd to me that someone with that much talent should take that stance. I’ve written a few things, and I’m not necessarily the best interpreter of them. Feelin’ Alright has never stopped, but it’s because Joe Cocker did it. When I heard Cocker’s version of that song I was like, “Oh, yeah!”

Where did you first meet Hendrix?

I met him one night in a club in London, Blazes. He was sitting by himself, so I just went and sat down and started talking to him. He was a fan of Traffic’s, and of course I was a huge fan of his. As many incredibly good guitar players as there are today, there are no more Jimi Hendrixs. He was something utterly unique, and like in any business I wanted to be around the best to learn from them. The two of us hung out quite a bit. At one point I was going to take Noel Redding’s place in the Experience, because there was a rift happening in the band.

You’re credited with playing the shehnai, an Indian oboe, on the Stones track Street Fighting Man. How did that come about?

That kind of stuff happened a lot back then. There were only so many studios, and everybody would be in London at some point, so you were bound to run into people. Chris Blackwell [Island Records head] had brought Jimmy Miller over from the States to produce Traffic, and Jimmy also ended up recording the Stones. Brian Jones I had also got to know. I just happened to be there at the session, and it was like: “Do you want to sit in and blow on this and bang some drums?” “Sure, why not.” It was just the lifestyle. You don’t know you’re making history when you’re doing it.

Next thing, you were living in LA.

When it was obvious that Traffic was a dead deal for me I just thought to hell with it, I’m going. Also, income tax was nineteen shillings in the pound [95 per cent]. It was insane. You could make more money on the dole than working. Screw that, I was heading west, young man. I took a bag of clothes and a guitar and left. There were still hippies on Sunset Boulevard when I got over there. I had no idea what was going to happen, but I met up with Delaney And Bonnie’s management, and through them got signed to Blue Thumb Records.

I cut my first solo album, Alone Together, with a lot of the Tulsa musicians from Delaney And Bonnie’s band. That was a great fucking band. That record also had Leon Russell and Rita Coolidge on it. At the same time, Clapton and Steve put Blind Faith together, and Delaney And Bonnie became the opening act on most of their American tour and I was the guitar player in that band. That’s how Eric got to find most of the people who went with him into Derek And The Dominos.

You were in Derek And The Dominos for just the one gig, at London’s Lyceum theatre, and then left.

Why? The problem for me was that Jim Gordon was the drummer in that band. He’s the guy who got Eric into heroin. Eric had just started on that path. We were all staying at Eric’s house, and there were a lot of days when nothing would get done. I eventually said: “You know what? This is great, guys, but I’m going back to the States.” As it happened, it turned out for the better for everybody. They went on with Duane Allman and cut Layla, which is a great album.

And you played on George Harrison’s album All Things Must Pass.

I kind of knew George. I had gone along to some of the Sgt. Pepper’s sessions and hung out with both Paul and George at different times. At George’s session I was one of a number of musicians, and if you asked me now what songs I played on I couldn’t tell you. I played acoustic guitar on two or three things, but I don’t know which ones.

What made you decide to go back to Traffic in 1971, and why did that reunion last only for six shows?

I went in thinking it would be the beginning of something and maybe that everybody had calmed down. There were a couple of other players in the band – Ric Grech on bass and Jim Gordon again – but nothing had really changed. The gigs seemed to have gone fine, but it was obvious that it wasn’t going anywhere. Or at least that’s how it was represented to me.

Back in LA, you made an album with Mama Cass.

That was an odd collaboration, let’s put it that way. It happened because when Gram Parsons introduced me around LA, he took me up to Cass’s house. It turned out that a couple of my best friends from London were also living there, so I spent most of that summer of 1969 at Cass’s. People would drop by like crazy.

By the time I came to make that album in 1971 The Mamas And The Papas were not happening, and Cass and I had been hanging out for so long we decided to try recording something together. Cass could have been another Sophie Tucker, she had a wicked sense of humour. But they never developed her that way in The Mamas And The Papas. She got cast as the big girl with the pretty voice, and she was so much more than that.

Cass, Parsons, Hendrix and Brian Jones – they had all died by 1974. How did that affect the way in which you viewed the business you were in and the lifestyle you were living?

Ah, I don’t think I ever thought much differently to the way I always had, to be honest. To lose that talent so young was obviously a great loss, but we’re all going to go at some point. That’s all part of us being here, and you just have to take life as it rolls and move on.

Let’s talk about some of the other people you had on your own albums. Each of Crosby, Stills and Nash independently popped up on your seventies records.

I knew Graham Nash. He and I had tried to do some writing back in England when he was still with The Hollies. When I moved over to LA, Graham was getting it together with Stephen and David. I was around the whole time that was going on. The three of them rented the house of Peter Tork from The Monkees, way up on the top of Mullholland Drive. They were all living there, kind of doing what Traffic had with the cottage. There was some loose talk of me coming on board with that at the beginning. Stephen and I also tried out a couple of things, but that didn’t pan out either.

How did Stevie Wonder come to play harmonica on The Lonely One on your 1973 album It’s Like You Never Left?

The two guys who were producing Stevie’s Innervisions album at the time were Bob Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil, and Malcolm was also working on my record. My sessions would sometimes follow on from Stevie’s, so I’d go down to the studio early to watch him work. One day I just asked if he would be up for playing on my track, and he was like: “Sure, absolutely.” He nailed it in two takes. The guy is amazing, a true genius.

And your duet with Michael Jackson, Save Me, on your 1980 album Old Crest On A New Wave?

Same deal. We were working in the same studio. I was in one room, Michael was in the other. He was on a break one day, and I had a song that I needed someone to sing a high part on. So I walked over to his room, introduced myself and asked him. He was actually stood in the doorway. He looked at me for a minute and then said: “You know, when I was twelve-years-old I did this TV special with Diana Ross, and at the end of the show we both sang this song together called Feelin’ Alright. So yes, I will come and sing on your song.”

All I wanted was for him to sing the one part, but he just went off and sang the whole track. He was dancing away behind the microphone.

Did anybody you asked to appear on a record ever say no to you?

Traffic. Ha!

How many fond memories do you have of the time you were in Fleetwood Mac?

The Fleetwood Mac cover band you mean? Mick Fleetwood I knew, and it was an interesting experience, but also very convoluted because there were three different managers, so it took forever to get anything done. We did that album [1995’s Time] that nobody even knows about, and Warner Brothers certainly didn’t promote; there were a couple of tours of Europe and the US and that was the end of that. It wasn’t one of the most productive times. Nowadays Mick is a neighbour on Maui and we’ve gotten to be very tight. I like him a lot.

Looking back over the whole span of your life’s work and many amazing experiences, could you possibly pick out a single highlight?

Good God, that’s hard, because there have been so many. I suppose if I have to choose one moment it would be sitting across from Hendrix, facing him with my acoustic guitar, Mitch Mitchell next to us, and laying down the track for All Along The Watchtower. That would rate up there.

Dave Mason's Traffic Jam tour is currently on the road in North America. This interview originally appeared in Classic Rock 259, published in January 2019.