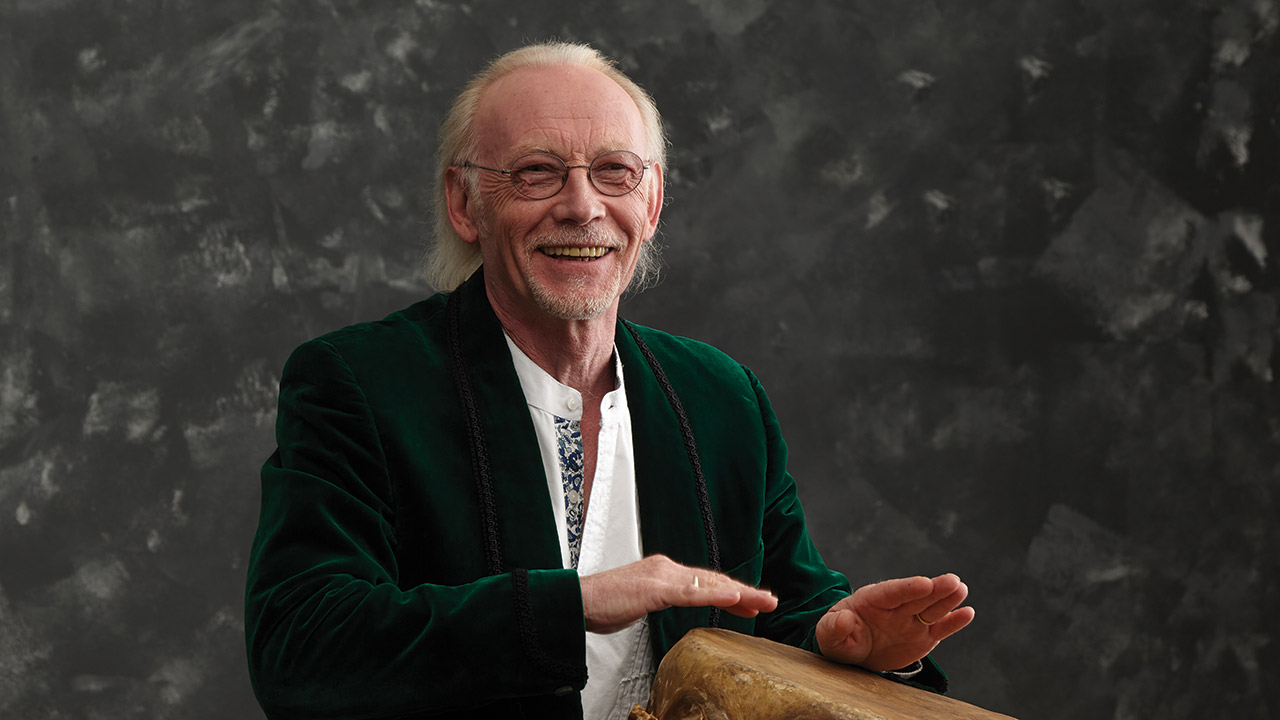

As a founder member of Gryphon, percussionist and vocalist Dave Oberlé was responsible for helping to bring quirkiness and curiosity to the band’s musical output. Inspired by medieval and renaissance music, jazz, rock and folk, he’s remained a constant within the band alongside Brian Gulland. He’s also guested on albums by Steve Howe, Wire and Gandalf’s Fist. In 2020 he looked back on a life that even led to him working on a metal magazine.

Dave Oberlé is mostly known for being one of the founder members of Gryphon, who were among the truly individual bands on the progressive scene in the 70s. Formed in early 1972, they released five studio albums before splitting up in 1977. While they never enjoyed major commercial success, Gryphon’s unique, quirky musical affectations were well received. They also toured incessantly, including the US with Yes in ’74.

The percussionist/vocalist has been part of the reactivated band since their reunion in 2015, during which time they’ve issued two more albums – 2018’s ReInvention and the recent Get Out Of My Father’s Car! And they continue to attract new fans.

Away from Gryphon, Oberlé contributed to the debut album from Wire, 1977’s Pink Flag, adding backing vocals on the track Mannequin. And he was also one of the guest vocalists on 2014 Gandalf’s Fist album A Forest Of Fey. Two years later, the band invited him back to sing on Pastor Simon from the album The Clockwork Fable.

Apart from his musical activities, Oberlé was the first advertising manager of Kerrang! Magazine, playing a key role in establishing it as the premier heavy metal publication in the 1980s. He was also, until recently, one of the directors of Small Blue, a computer software company.

Do you come from a musical family at all?

Well, my mother played the piano, and that had an influence on me. I recall standing next to her as she played both classical and contemporary stuff.

What was the first instrument you played?

When I was four or five years old, I found a pair of meat skewers in a wooden box and started to use them as makeshift drumsticks. From there I was hooked on the idea of being a drummer.

What appealed to you about becoming a percussionist?

You mean apart from the joy of hitting things? I had a good sense of rhythm, which I probably inherited from my mother, and from there I got into how musical sounds were constructed.

Did you have any lessons?

None at all. I’m completely self-taught. When I was nine my parents bought me a snare, and that was my first proper drum. I recall there were always lots of complaints from Mum and Dad about how loudly I was hitting that snare. Most kids were asked to turn down the stereo or the radio. I was told to dampen the sound of the drum!

When I joined Gryphon I didn’t even know I could sing

Who are your vocal heroes?

I never really had any. To be honest, when I joined Gryphon I didn’t even know I could sing. I mean, I knew I could carry a tune, but I’d never tried it in public before. Brian Gulland was a trained chorister and had perfect pitch, so he seemed the obvious choice as the band’s vocalist. However, it turned out that I had a decent voice, and that’s why I ended up doing most of the vocals on our first, self-titled album [1973].

What was your first band?

I was in quite a few at school. One of them was with Philip Nestor, Gryphon’s original bassist. I was 13 or 14 at the time and we didn’t even have a name. I suppose the first proper band I had were called Juggernaut. That was with a bloke called Ray Rhoades; we played heavy rock with progressive moments. We were together in 1968, so just a couple of years before Gryphon started.

How did Gryphon get together?

Brian Gulland and Richard Harvey [mandolin, keys, recorder] were studying at the Royal College Of Music in London. They had an interest in folk, medieval and renaissance music, which is what inspired them to form the band. Graeme Taylor joined them two or three months later, and they got me involved a short time after that.

You had an unusual sound. How was it developed?

We had no plan – it just happened. You could do that sort of thing in the early 70s. The world was our oyster. We began as a folk band, playing all the usual bars and venues on that circuit. The Gryphon album was mostly made up of folk songs and medieval dances. Juniper Suite was the sole original band composition. That set us off on the path we took.

Do you feel your albums in the 70s captured what the band were about?

The wonderful thing about this band was that we never recorded an album that sounded like its predecessor. So Midnight Mushrumps [1974] didn’t sound like the debut, and Red Queen To Gryphon Three [also 1974] was nothing like the first two. We set out to make every album totally different to what had come before. There was no formula involved.

I believe that was part of our appeal: the ability to make our records self-contained, as it were. Yes, you did run the risk of losing some fans along the way, but you also gained new ones.

You toured the USA with Yes. Was that a career highlight?

Absolutely. We went from playing 1,000-to-1,500-capacity venues to performing in

the biggest stadia around, before 40,000 fans or more. It was definitely career changing. We were promoting Red Queen To Gryphon Three at the time, and it got a really good reception.

It wasn’t a good period for us… we were under pressure to become more commercial, which wasn’t our style

I think the biggest show on that tour was the Houston Astrodome [on December 2, 1974]. Yes headlined, with the Mahavishnu Orchestra second and us as the openers. But the greatest thrill was doing Madison Square Garden [on November 20]. When we came offstage, there was a neon sign flashing across the venue which said, ‘New York Welcomes Gryphon.’ I recall thinking to myself, ‘We’ve made it!’ We did a lot of dates on that tour in a very short space time, and sometimes it would involve travelling a few hundred miles overnight to the next city. It was exhausting but worthwhile.

Why did Gryphon split up in ’77?

To some extent it was down to punk coming along. That was such a game-changer for us. People no longer wanted to see a band all dressed up and with

a big light show – all they wanted were four blokes onstage with one light bulb.

But you’d just signed a new deal with the Harvest label…

Yes, we left Transatlantic, who had put out our four previous albums, and released Treason for Harvest. But that wasn’t a good period for us. We were managed by Brian Lane, who also represented Yes, and were under a lot of pressure to become more commercial, which wasn’t our style at all.

Mike Thorne was the producer for Treason; not only did he produce the Sex Pistols but also effectively discovered them. We could see there was an imbalance between what we were doing and what the Pistols were up to. It hammered home that our time was up.

Looking back, if we had started two or three years earlier, then the band may possibly have established itself more and been able to ride out the storm the way Yes, Jethro Tull and Genesis all managed. We were just a little too late coming to the party.

You guested on the first Wire album the same year. How did that come about?

Ironically, that was through Mike Thorne. He produced the Pink Flag album and asked me if I’d like to sing on it, and I was happy to.

During the 80s, you were Advertising Manager for Kerrang! – how did you adapt to that change in circumstances?

I’d always been interested in keeping up with what the music press was writing. Having come out of a band, it was a big shock to suddenly have to find a job. I worked for Melody Maker, then Sounds and finally I was involved with the launching of Kerrang!. I’m extremely proud of my role on that magazine. We had fantastic success, even if we were treated by the publishers as some sort of pariahs. They never seemed to appreciate how much money we were making for them. There was another big plus in being employed: it meant I got a regular income. Anyone who has been in a band will know how perilous that existence can be, and you can struggle to make any money.

There was no desire to go back to being a full-time musician… I was enjoying having money in my pocket

When the neo-prog movement sprung up, thanks to bands like Marillion and Pallas, did you start to feel like you wanted to play regularly again?

The arrival of those bands didn’t really have much impact on me. I was playing drums for local acts in pubs ; nothing too serious, but it meant I was keeping my hand in. However, there was no desire from me to go back to being a full-time musician. As I said, I was enjoying having money in my pocket.

Your old Gryphon pal Richard Harvey became a very successful composer for films and TV shows. Did that ever appeal?

Not at all. It’s a lonely existence. You sit in front of a computer composing the music for images you see on the screen, and you’re all alone. The only time you’ll get to hear what you write being performed is when an orchestra play it in the final version of the movie or TV show. Richard works alongside Hans Zimmer a lot these days, and he’s taken to doing live performances to break the monotony of being cooped up composing. That sort of life could never have any appeal for me.

What prompted the one-off Gryphon reunion for a show at Queen Elizabeth Hall, London in 2009?

At the time we had a Gryphon page on the internet; it was our only media outlet. Someone in Portugal set it up for us, and we were amazed to find it had more than 200,000 hits. We had no idea the band were still so popular – for us it was a revelation. So, as there was never the chance to do a farewell gig once we’d decided to call it a day in 1977, it was felt we should get back together and see how it went.

Was it hard work to get back into the Gryphon mindset for the gig?

We’d booked the Queen Elizabeth Hall, and immediately wondered if it was a bad mistake. Would anyone actually buy a ticket to see Gryphon? To our delight we sold out the venue. But we had to work very hard to make sure the band were up to the task.

We brought in Jonathan Davie, who played bass on Treason, and Graham Preskett to help us out: two excellent musicians. And we spent a month rehearsing. It was really like being in boot camp – but it was necessary, because our music is very complex and it had been so long since we last played together. However, it was all worthwhile, because the gig was a massive success. Better than we could ever have expected. And as a result, there were discussions about doing a new album. That seemed to all of us to be a logical move. The enthusiasm we all felt for the band was undeniable and the plan was to take it to the next stage.

Why didn’t it go any further at the time?

The simple answer is that none of us had the time to devote. Richard was doing his musical scores and the other guys also had projects taking up their time. But there were no problems between us at all, and we kept in touch regularly.

You had a computer software company, didn’t you?

My partner Sally had the company, really. I was a director, but very much in the background. I never got actively involved. It takes all my ingenuity just to turn on a computer – ha!

Gryphon properly reformed in 2015. How did that happen?

We were all suddenly available. As I said, all of us had been talking anyway, so as soon as the opportunity arose we were in complete agreement it should happen.

You’ve also guested on two albums from Gandalf’s Fist. How did that come about?

I was asked by Dean Marsh from the band if I’d do some vocals for them. As it turns out, Dean is a big fan of Gryphon. I like Gandalf’s Fist and the way they operate, so was happy to help them out. It was a fun thing to do. I get on very well with Dean and also Stefan Hepe. They seem to be very self-contained and understand how to make the band financially viable, and in this day and age that’s vital.

Have you had any other offers to guest on albums?

I did guest on Martin Orford’s solo album, The Old Road [2008]. It was nice to be asked alongside others such as John Wetton, John Mitchell and David Longdon. I’m on the title track. It was Martin’s last album before he retired from music. Honestly, he’s a kid compared to me, so I hope he’ll return to action before too long. Look, if I can still do it at my age, then there’s no excuse for him to remain inactive!

Away from Gryphon, what else are you working on?

I don’t do anything aside from work on Gryphon stuff. It takes up all of my time, because there’s so much to do these days.

Gryphon are now very much a cottage industry, aren’t you?

We are. We’ve formed ourselves into a limited company, and do everything ourselves. In the 70s, bands had managers, labels and booking agents – for better or for worse. The prog world was very different back then, and there was so much money involved. Of course, having all these people working on your behalf meant you could sometimes lose track of where all the money went.

Now we have it all under our own control. We put out albums on our own label. We manage ourselves and book all the gigs. This way we know what’s happening and when. Is it better for the band than the way it was all those years ago? Yes, it is. Why would we need anyone else to look after our affairs? It would have been impractical in the 70s, but the more experience you get being in a band, the more you appreciate having the ability to make your own decisions. There were some terrible choices made on our behalf in the past. Now, we only have ourselves to blame if anything goes wrong.

We’re mainly an instrumental band and that means there are no language barriers

You have a global fanbase. Why do you think you appeal to so many different nationalities?

Because we’re mainly an instrumental band, and that means there are no language barriers. You’re right; we have fans everywhere – that’s something social media has highlighted. Looking at our Facebook page, it’s amazing how far our reach is. It would be wonderful to play in countries we’ve never been. That sort of thing keeps us all fresh. A new challenge.

What would you say is Gryphon’s biggest achievement?

I would have to say the fact we’ve been able to make every album different and individual. A lot of bands were bigger than us, but few can claim to have such

a diverse catalogue of music. When I look back at that alone, I know it’s all been worthwhile. I may not have a mansion or a yacht, but in Gryphon we’ve always been truly creative.