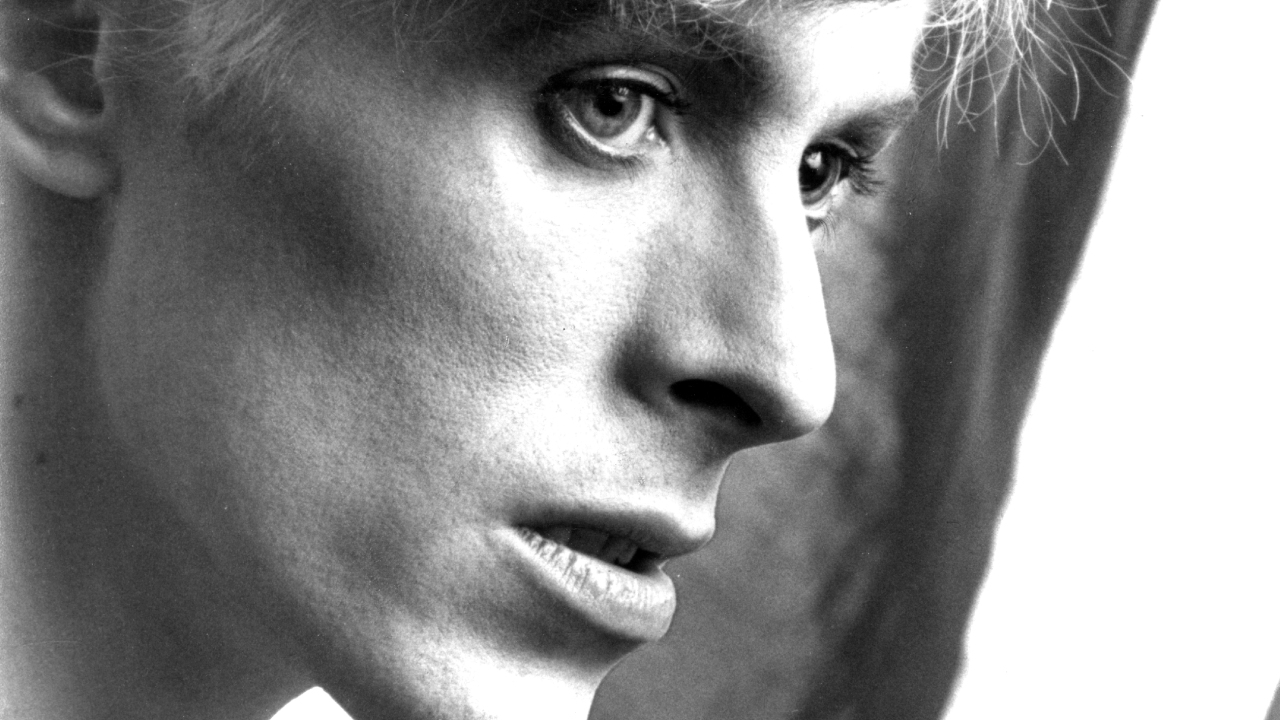

“I’ve still got that same thing about when I get to a country or a situation and I have to put myself on a dangerous level, whether emotionally or mentally or physically,” said David Bowie in 1977.

“Living in Berlin… forcing myself to live according to the restrictions of that city.”

At the end of 1976 David Bowie was in West Berlin finishing two albums: his own Low, and the solo debut by his friend Iggy Pop, The Idiot. Having left Los Angeles to escape both the American music business and his own cocaine habit (which had in turn fuelled his paranoia and an interest in the occult), Bowie was keen to approach some sort of normality. He chose to do so in Europe’s most surreal location, a former capital city populated on one side of a big wall by secret police, Communists and imprisoned locals, and on the other side by junkies, misfits and artists.

For many people in Britain 1977 was a pretty exciting year; if you weren’t wrapping bunting around a trestle table for the Silver Jubilee, you were wondering about putting a safety pin through the cat’s ear. Everyone said they were bored but nobody really was.

And Bowie was far from an exception. He began 1977 celebrating his 30th birthday in a nightclub drinking with Iggy. He ended it on American television crooning Christmas songs with Bing Crosby. Along the way he said farewell to his first serious rival and best friend, Marc Bolan, spent a lot of time in the studio, and changed the course of popular music for ever.

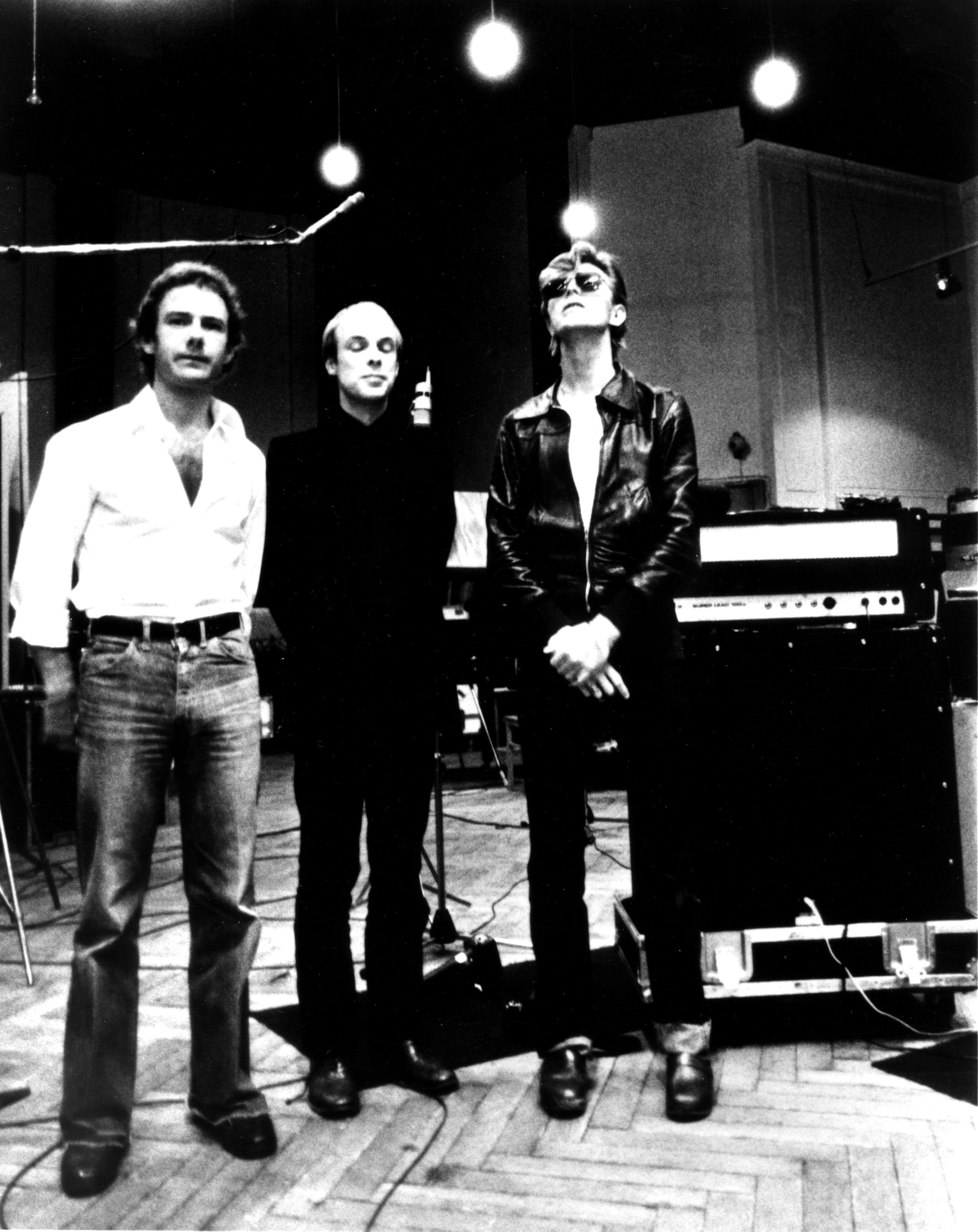

Having recorded Low mostly in France with Tony Visconti – possibly the only album ever made with contributions from Brian Eno, Iggy Pop and Eurovision singer Mary Hopkin (Visconti’s then wife and an Apple Records hit-maker with Those Were The Days) – Bowie had found a new way of working and a new music (Low’s working title was New Music Night And Day).

He had left behind Ziggy, Aladdin Sane and, more importantly, The Thin White Duke – the mildly fascist, somewhat Kabbalah-influenced rock demon which was his most dehumanised persona yet. Low also left America behind, its synth washes, disinterested vocals and brittle funk owing little to rock and soul and a lot to the future. Right to the fore was Visconti’s new acquisition, the Eventide H910 Harmonizer pitch shifter, which the producer famously sold to Bowie and Eno with the phrase: “It fucks with the fabric of time.”

Duller critics sometimes call Low soulless, or empty, as though not actually crying while singing makes music emotionless. Bowie himself said: “There’s oodles of pain in the Low album. That was my first attempt to kick cocaine, so that was an awful lot of pain.”

The Idiot was even further. With Pop’s brilliant lyrics, songs like Sister Midnight and Nightclubbing were both sexy and sinister, ominous and exciting, while Dum Dum Boys provided a dark eulogy for The Stooges, and China Girl (‘visions of swastikas in my head’) became a worldwide pop hit when Bowie covered it in 1983. Most remarkably, Bowie and Iggy – a man who in many ways is American rock at its most extreme – created one of the great European albums (although, as Bowie put it” “Poor Jim, in a way, became a guinea pig for what I wanted to do with sound.”)

In 1976 Bowie had toured the world with Station To Station, introducing Iggy to life in stadium rock. In ’77 Bowie became Pop’s on-stage keyboard player on a UK tour beginning at Aylesbury Friars Hall and visiting Newcastle, Manchester and Birmingham before ending in London, where Bowie met up with his old friend and rival Marc Bolan. They went for several drinks and were spotted in the King’s Road shouting: “I’m Bowie!” and “I’m Marc Bolan!”

After a brief American tour, Iggy and Bowie returned to Berlin where, incredibly, they made a third album in ’77, Lust For Life. This time Pop was holding the reins; Lust For Life, as its name suggests, is rock, albeit a new kind of rock. “See, Bowie’s a hell of a fast guy,” said Pop. “I realised I had to be quicker than him, otherwise whose album was it gonna be? The band and David would leave the studio to go to sleep, but not me.” Guitarist Ricky Gardiner wrote the brilliant riff for The Passenger, while Bowie worked out the title track on the least futurist instrument available, the ukulele. Again Bowie was to have a hit with a song from the album: Tonight (minus Iggy’s terrifying spoken intro but plus Tina Turner).

After a brief break for, possibly, coffee and sandwiches, Bowie, Visconti and Eno reconvened to make another album. Heroes is a less sketchy, more focused album than Low and in the title track contains one of Bowie’s greatest songs. With a lyric that Visconti claims is about his affair with singer Antonia Maas, the track Heroes features Robert Fripp, whose guitar playing was matched only by his fondness for obscure sexual similes like “waving the sword of union”. Bowie’s desire to experiment continued with his use of Eno’s randomising Oblique Strategies cards and, as with Low, a side of instrumental tracks.

After the completion of his fourth album in 12 months, Bowie appeared on Marc Bolan’s TV show Marc (Bolan fell off the stage during the recording, prompting Bowie to enthuse: “Oh, that’s really Polaroid!”). The pair’s reunion was short lived. Bolan was killed in a car crash the same month. Bowie also recorded Peace On Earth/The Little Drummer Boy with Bing Crosby for a TV special. “I was wondering if he was still alive,” Bowie told me in 1999. “He was just… not there. He was not there at all. And he looked like a little old orange sitting on a stool. It was the most bizarre experience.” In November there was a Kenyan safari with his son, Best Man duties for his driver in December, and that was it. Oh, apart from doing the LP narration of Prokofiev’s Peter And The Wolf, making it technically five albums recorded in a year.

And that was it for 1977. In those 12 crammed months Bowie had gone from being a recovering LA rock star stuck in an eternal Sunset Boulevard of the mind, to someone who would change popular music for the next 10 years. The introspective music of Low, Heroes and The Idiot was in fact a way of bringing Bowie out of himself. And a man nearly wrecked by drugs and success was saved by, of all things, art and intelligence. Best of all, a radical change of scene from a man who’d claimed he was always crashing in the same car resulted in four of the greatest albums of all time. What most artists would be able to call the fruits of a long and successful career took David Bowie a year. And what a year.

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #173.

For more on Bowie and the story behind the song Heroes, then click on the link below.