January 1971. There was trouble in outer space. Major Tom’s signal was growing fainter by the day. And Ziggy Stardust was still an undefined blip on the interstellar radar.

Meanwhile, back at ground control, David Bowie was staring at the grey sky outside his Beckenham flat and worrying about his career.

His last single, The Prettiest Star, had been a flop, failing to build on the momentum of Space Oddity. His third album, The Man Who Sold The World, was languishing in the vaults of Mercury Records without a firm release date. His guitarist, Mick Ronson, had moved from London back to Hull to work as a gardener.

Meanwhile, Bowie had fired his manager of five years, Ken Pitt. Although Pitt’s replacement, the cigar-chomping Tony Defries, had offered the age-old promise of “I’ll make you a star”, nothing celestial had yet materialised. In fact Defries’s most significant gambit at that point had been a financial squeeze-play that ousted Tony Visconti, robbing Bowie of both a producer and close friend. Alienated and in serious limbo, Bowie was reduced to gigging at pubs around south London for a few pounds a night.

In an unguarded low moment, he admitted to journalist Steve Peacock that he felt “washed-up – a disillusioned old rocker”.

At 24, with seven years in the business, three albums under his belt and one too many thwarted dreams, Bowie brooded on the sidelines as his friendly rivals Marc Bolan and Elton John ascended the first rungs of the ladder to stardom. When would he get his turn?

But even in his winter of discontent, Bowie refused to quit. “I might have had moments of, ‘God, I don’t think anything is ever going to happen for me,’” he later said, “but I would bounce up pretty fast. I still liked the process. I liked writing and recording. It was a lot of fun for a kid.”

After years of aping R&B and coffee house folk styles, the blond-tressed kid was finally discovering his own sound. Or, as he’d put it so poetically in a song he’d written that December, he was learning to ‘Turn and face the strange’.

“In the early 70s it really started to all come together for me as to what it was that I liked doing,” Bowie tells Classic Rock, “and it was a collision of musical styles. I found that I couldn’t easily adopt brand loyalty, or genre loyalty. I wasn’t an R&B artist, I wasn’t a folk artist, and I didn’t see the point in trying to be that purist about it. My true style was that I loved the idea of putting Little Richard with Jacques Brel, and the Velvet Underground backing them. ‘What would that sound like?’ Nobody was doing that, at least not in the same way.”

This revelation would help create Hunky Dory, the kaleidoscopic pop collection that announced Bowie’s arrival and began a streak of landmark albums through the 1970s – from Ziggy Stardust to Aladdin Sane to Heroes.

Bowie’s artistic vision was doubtless brought into sharper focus by a dose of domestic reality – he was about to become a father for the first time. Ex-wife Angie Bowie says: “I think that changed how he was writing songs. He really started to think about how he was going to have a kid. That was interesting to him. He got along very well with his father, so from that relationship he had an optimistic prognosis on what it was going to be like. It wasn’t a scary thing for him. Changes and Eight Line Poem were about that. And, of course, Kooks.”

David and Angie, the self-described “kooky” couple, lived in an eight-pound-a-week, ground-floor flat in a Victorian-era mansion called Haddon Hall. Furnished with Carnaby Street bric-a-brac, art-deco lamps, Oriental rugs from Kensington Market, and heavy black drapes blocking out the already dim natural light, it was the Bowies’ version of a decadent pop-star pad. Or, as one visitor had it, “It looked like Dracula’s living room.”

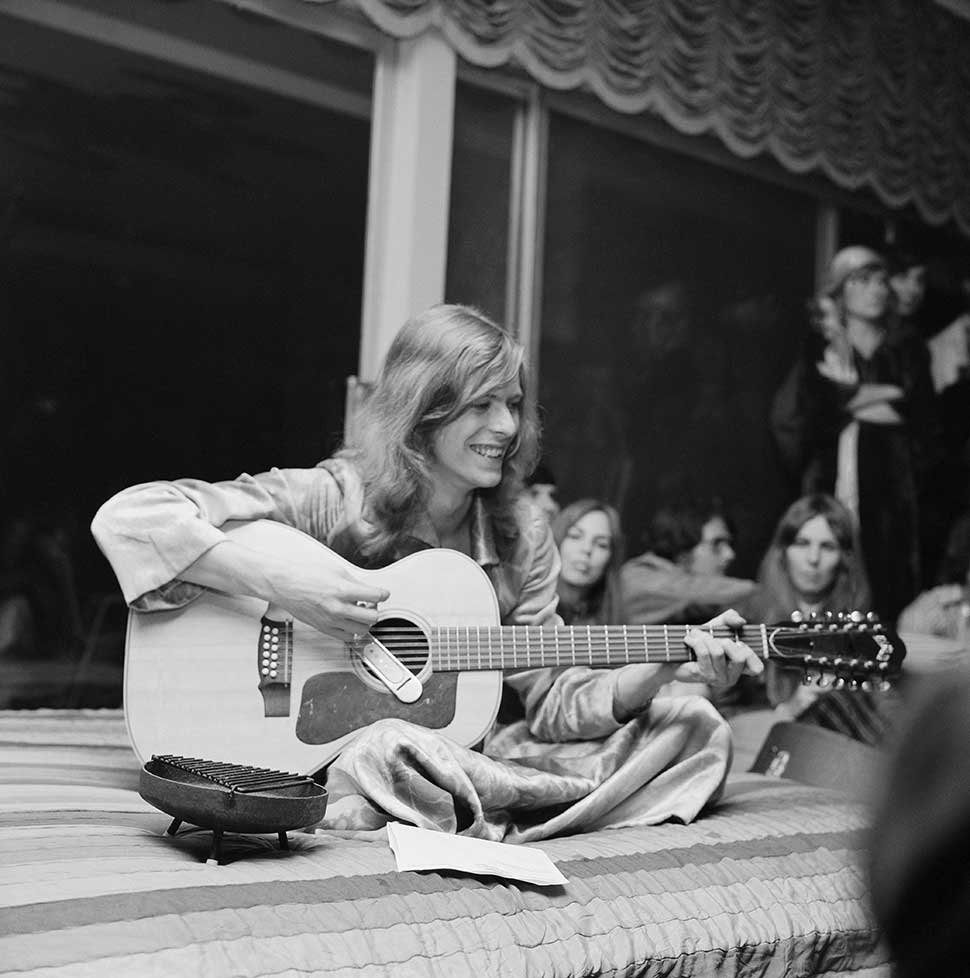

In those early months of 1971, Count Bowie could often be found hunched over Haddon Hall’s centrepiece, an ancient grand piano. Swapping his usual instrument, a Harptone 12-string acoustic guitar, for the less-familiar keyboard had a galvanising effect on his songwriting.

“He loved that piano,” Angie remembers. “David is a fantastic musician, because his approach is not studied, it’s by ear. He has an ability to pluck a song from those first moments when he plays with an instrument. Writing on the piano opened up his possibilities, because of its association with so many kinds of music – classical, cabaret, every style.”

Bowie was also discovering interesting possibilities at his new favourite nightclub, a gay disco in Kensington called the Sombrero. Enchanted by the sexual freedom and outré hair and make-up on display, he found inspiration for both his songs and his own appearance. “Oh, You Pretty Things came directly out of David observing that scene, as did his [Ziggy] look,” Angie says.

Excited about his growing cache of songs and ideas for a new direction, he rang Mick Ronson, saying: “There’s nothing doing up in Hull, is there? Why don’t you come back here? You can stay with me and Angie.” With the promise of recording sessions and a place to crash, Ronson, with drummer Woody Woodmansey and bassist Trevor Bolder in tow, moved into Haddon Hall.

Woodmansey, who had played on Bowie’s The Man Who Sold The World was immediately struck by Bowie’s new material. “I think he focused more as a writer and managed to keep his unique approach, especially lyrically, while streamlining everything,” he says. “The songs were more structured. Honestly, I didn’t think he had these songs in him.”

Bolder, who’d been playing with Ronson and Woodmansey for about eight months in the band Ronno, was also surprised. “I had an impression of Bowie as a bit of a folkie. I didn’t realise how good he was until we started doing Hunky Dory.”

In the makeshift studio at Haddon Hall or in a practice room above the nearby Thomas A. Becket pub, Bowie and the future Spiders From Mars began working up arrangements for songs such as Changes and Oh, You Pretty Things (which had already been covered and taken to No.12 in the UK singles chart by Peter Noone), as well as Ziggy tunes like Hang On To Yourself, Suffragette City and Moonage Daydream.

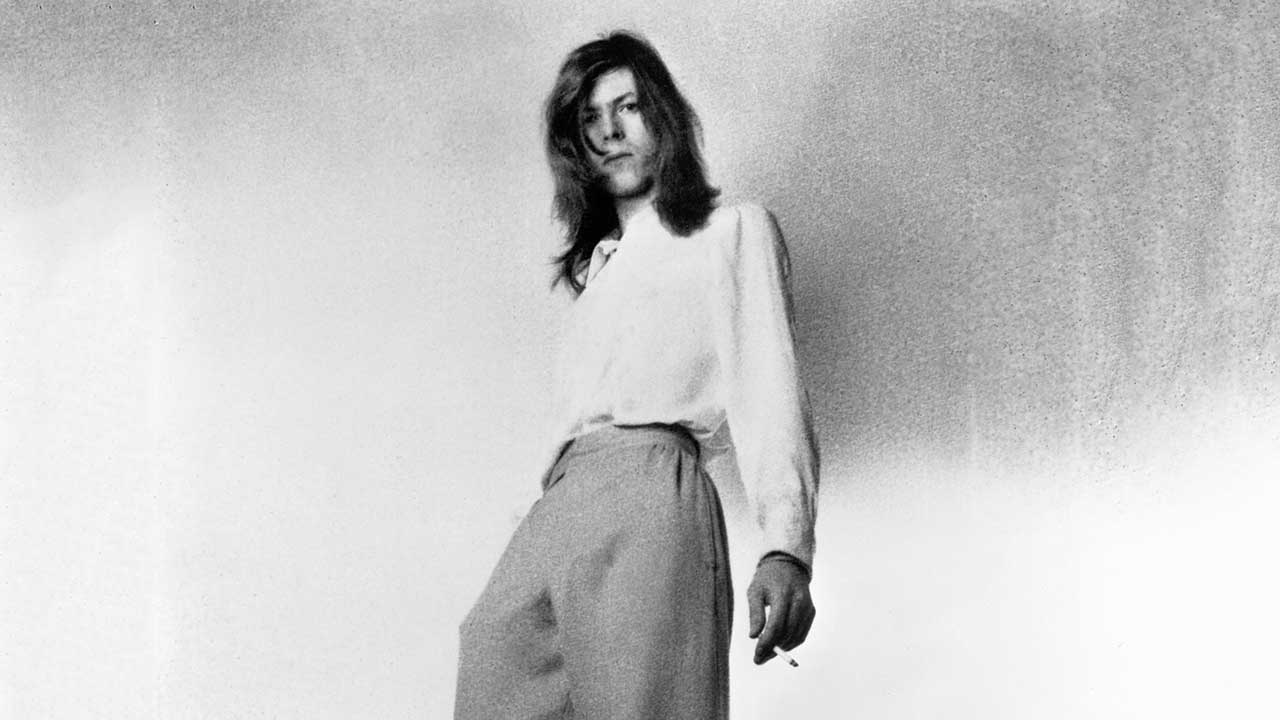

At the end of January, Bowie departed for a promotional tour of america, his first-ever visit. he was greeted at customs by a snarling dog, and an official who detained him for over an hour. Maybe it was the full-length purple suede coat and white chiffon scarf Bowie was sporting. Or his suitcase, which was packed with six dresses by designer Mr. Fish. The customs official finally sent the long-haired singer on his way with a mumbled parting shot of “fag’.

But Bowie was too excited to let that get him down. at last he was in the land of his heroes Jack Kerouac and andy Warhol. Over the next two weeks, he crossed the country, chatting up radio DJs and journalists about The Man Who Sold The World (the UK sleeve, featuring Bowie lounging in one of his dresses, was replaced in the US with a pop-art drawing of a cowboy). at night Bowie indulged, swallowing as many pills and bedding as many women as he could. But what fascinated him most about america were two artists and kindred spirits-to-be: Lou reed and Iggy Pop. Bowie scrawled down an idea for “an ultimate pop idol” who would combine reed’s urban songwriting with Iggy’s cartoon stage persona. But before Ziggy Stardust was born, reed and Iggy would etch their way into the grooves of Hunky Dory.

“The whole Hunky Dory album reflected my new-found enthusiasm for this new continent that had been opened up to me,” Bowie said in 1997. “It all came together because I’d been to the States. That was the first time that a real outside situation affected me so one-hundred per cent. It changed my way of writing and changed the way that I looked at things.”

Before he flew back to London, Bowie made his artistic resolve clear to Rolling Stone magazine: “I refuse to be thought of as mediocre. If I am mediocre, I’ll get out of the business.”

Upon his return, rehearsals resumed – by now Ronson, Woodmansey and Bolder had rented their own flat in nearby Penge – and plans were made to record an album, which Tony Defries would then use to secure a new label deal. But first a producer had to be found.

As engineer on Beatles classics from Sgt. Pepper to Abbey Road, as well as on Bowie’s previous two records, Ken Scott seemed a logical choice (Bowie would later call Scott “my George Martin”).

“I was getting fed up with engineering,” Scott told EQ magazine, “and I happened to say to David: ‘I want to start moving into the production side.’ he said: ‘Well, I’ve just got a new manager and I’m about to start a new album. I was going to do it myself but I don’t know if I can. how about working with me?’ and that was Hunky Dory, which then led to the other three albums.”

Sessions began at Trident Studios in London’s Soho in early June 1971. In the world outside, US president nixon ended a 21-year-old trade embargo on China; Russia launched the Soyuz 11 craft for the first-ever rendezvous with a space station; Frank Sinatra announced his retirement; and topping the pop chart in Britain was Tony Orlando & Dawn’s Knock Three Times.

Inside Trident, however, none of that registered. Working from 2pm to midnight, Monday to Saturday, with quick breaks for tea, sandwiches and the occasional bottle of wine, the band were swept up in a colourful world of bipperty-bopperty hats, Garbo’s eyes and homo superiors (the album’s recurring theme of children ch-ch-changing into enlightened beings was influenced by Bowie’s love of the occult writings of Aleister Crowley, and sci-fi novels by Arthur C Clarke).

Bolder recalls the excitement: “Hunky Dory was the first recording session I ever did in my life, and just to be in a studio was amazing. Our approach was very off-the-top-of-our-heads. We’d go in, David would play us a song – often one we hadn’t heard – we’d run through it once and then take it. no time to think about what you’re going to play, you’d have to do it there and then. In some respects it’s nerve-racking, but it gives a certain feel. If you play a song too many times in the studio it can become stale, and I think David wanted to capture the energy of it being on the edge.”

Woodmansey agrees: “There was incredible pressure in getting a track recorded right. Many times, we’d go in with a track to record, and at the last minute David would change his mind and we’d do one we hadn’t rehearsed! We would be panicking, as he didn’t like doing more than three takes to get it. nearly every track I recorded with David was first, second or third take, usually second. he knew when a take was right.”

This was a change from the sessions for the previous album, where Bowie was reportedly distracted and undisciplined. Tony Visconti later complained that during the recording of The Man Who Sold The World David had spent more time in the lobby cuddling with Angie than worrying about finishing the tracks. But the Bowie on Hunky Dory was a man with a mission

Ken Scott: “With David, unlike the Beatles sessions, it was very much him knowing what he wanted right from the get-go. I think he knew all along what was going to happen, but he didn’t always tell you. you had to be ready. and with David almost all of the lead vocals are one take.”

A late addition to the team was keyboard virtuoso Rick Wakeman, who had played Mellotron on Space Oddity and was now drafted in to dress up Bowie’s piano parts. “he told me to make as many notes as I wanted,” Wakeman once said. “The songs were unbelievable – Changes, Life On Mars?, one after another. he said he wanted to come at the album from a different angle, that he wanted them to be based around the piano. So he told me to play them as I would a piano piece, and that he’d then adapt everything else around that.”

If Wakeman was a featured performer so too was the 100-year old Beckstein piano he played. Scott: “It was the same piano used on Hey Jude, the early Elton John albums, Nilsson, Genesis and Supertramp, among many others. That was one of Trident’s claims to fame – the piano sound. It was an amazing instrument.”

Nowhere was that piano better featured than on the kitchen-sink ballad Life on Mars? The song has often compared to Sinatra’s My Way (the album liner notes even say: “Inspired by Frankie”), and for good reason. In 1968 Bowie was asked by a publisher to submit English lyrics to a popular French chanson, Comme D’Habitude. his version, titled Even A Fool Learns To Love, was rejected in favour of another by former teen idol Paul Anka.

Bowie: “There was a sense of revenge in that, because I was so angry that Paul Anka had done My Way. I thought I’d do my own version. There are clutches of melody in that [Life On Mars?] that were definite parodies.”

A week before the sessions began, on May 30, Duncan Haywood ‘Zowie’ Jones was born, cracking his mother’s pelvis in the delivery. Bowie greeted his boy with Kooks, a charming ditty meant as both a paternal tribute and a warning. In the 1971 press release for Hunky Dory, he explained: “The baby looked like me and it looked like Angie and the song came out like, ‘If you’re gonna stay with us you’re gonna grow up bananas.’”

Actually, Zowie (now known as Duncan Jonesand an acclaimed film director) turned out fine, despite a mostly absentee father and being raised by a revolving cast of nannies and grandparents. Bowie confesses: “I might have written a song for my son, but I certainly wasn’t there that much for him. I was ambitious, I wanted to be a real kind of presence. and I had Joe very early. and with that state of affairs, had I known, it would’ve all happened a bit later. Fortunately everything with us is tremendous. But I would give my eye teeth to have that time back again, to have shared it with him as a child.”

Drawing on the “collision of musical styles” idea, Hunky Dory ricochets playfully through its 11 songs. From the lounge-meets-boogaloo gear shifts of Changes and the glam-ragtime stride of Oh, You Pretty Things, through the Tony newley-does- the-blues of Eight Line Poem to psyche-Dylan swirl of The Bewlay Brothers, it’s a thrilling hybrid.

“It was like, ‘Wow, this is no longer rock’n’roll. This is an art form. This is something really exciting!’” says Bowie. “I think we were all very aware of George Steiner and the idea of pluralism, and this thing called post-modernism which had just cropped up in the early 70s. We kind of thought, cool, that’s where we want to be at. Fuck rock’n’roll! It’s not about rock’n’roll any more, it’s about how do you distance yourself from the thing that you’re within? We got off on that. I think certain things had been done that were not dissimilar, but I don’t think with the sensibility that I had.”

That sensibility was abetted by the album’s secret weapon: guitarist and creative foil Mick Ronson. “What I’m good at is putting riffs to things, and hook-lines, making things up so songs sound more memorable,” the guitarist (who died in 1993) once said. and the proof abounds: his spare, searing licks on Eight Line Poem; the explosive acoustic on Andy Warhol; the nasally distorted power blast on Queen Bitch. all electrifying moments.

“I would put him up there with the best I’ve ever worked with,” said Ken Scott. “I think Ronno was better than any of The Beatles as a guitarist. his playing was much more from a feel point or melodic point of view.”

Woodmansey: “Mick didn’t really know how good he was. he would do a solo, first take, never played it before, and it would blow us away. David would always get Ken to push the record button without Mick knowing. he would do another six solos, but it was always the first or second one that we kept.”

Ronson’s gifts extended beyond his guitar playing. In the months prior to the sessions, he had been studying music theory and arranging with a teacher back in Hull. That bit of knowledge, combined with his innate musicality, made for the stunning string arrangements on songs like Life On Mars? and Quicksand.

“Ronno was great the way he’d go down to just one or two violins, then have the others come slowly but surely,” says Scott. “he didn’t quite know what he was supposed to do, so he was much freer. Much like The Beatles. he would do things other arrangers would never do.”

Angie Bowie says of the communication between her ex-husband and Ronson: “They were two Yorkshireman chatting away. Very full of respect for each other. They were young and very sweet, well-mannered, trying to be as professional as they could. I know that sounds boring, but it’s the truth. There were no drugs. They were just doing this wonderful album and everyone was thrilled at having a chance to participate instead of having to work horrible jobs.”

Side Two of the album featured a trio of “hero songs” inspired by Bowie’s visit to America. Queen Bitch was an exhilarating nod to the Velvet underground (Lou reed later said he “dug it”). Bowie says he had been fixated on the Velvets since the first time he heard their single Waiting For The Man. “It was like, ‘This the future of music! This is the new Beatles!’ I was in awe. For me it was a whole new ball game. It was serious and dangerous and I loved it.”

For this coded tale of seduction, Bowie taps into reed’s style of urban poetry, even tossing in new york-isms like ‘you betcha’. as the only electric guitar-dominated track on Hunky Dory, it also previews the shapes of things to come on Ziggy.

Of Song For Bob Dylan, Bowie said in 1976: “That laid out what I wanted to do in rock. It was at that period that I said: ‘Okay, Dylan, if you don’t want to do it, I will.’ I saw that leadership void. even though the song isn’t one of the most important on the album, it represented for me what the album was all about. If there wasn’t someone who was going to use rock’n’roll, then I’d do it.”

As for the song Andy Warhol, Bowie wrote what he thought was a tribute. That is until he returned to New York in September 1971 and played it for Warhol. “he hated it,” Bowie recalls with a chuckle. “Loathed it. he went [imitates Warhol’s blasé manner] ‘Oh, uh-huh…’ then just walked away. I was kind of left there. Somebody came over and said: ‘Gee, andy hated it.’ I said: ‘Sorry, it was meant to be a compliment.’ ‘yeah, but you said things about him looking weird. Don’t you know that Andy has a thing about how he looks? he’s got a skin disease and he really thinks that people see that.’ It didn’t go down very well.

“I got to know him after that. It was my shoes that got him. They were these little yellow things with a strap across them, like girls’ shoes. He absolutely adored them. Then I found out that he used to do a lot of shoe designing when he was younger. he had a bit of a shoe fetishism. That kind of broke the ice.”

The album’s cryptic closer, The Bewlay Brothers, with its images of ‘mind warp pavilions’ and ‘grim faces on cathedral floors’, has been one of the most analysed of all Bowie’s songs, with interpretations finding everything from a gay manifesto to an account of Bowie’s relationship with his schizophrenic half-brother, Terry.

Angie: “It’s always a good idea to get a two-fer: write a song and get your therapy. I always teased him about that one, because it was a big, autobiographical confessional song. all folk singers have to write a few of those.”

Ken Scott offered a different take: “That was almost a last-minute song. Just down the street from Trident, there was a tobacconist which apparently gave him the inspiration for the name. He’ll probably deny this to death. as I remember, he came in and said: ‘We’ve got to do this song for the American market.’ I said:, ‘Okay, how do you mean?’ he said: ‘Well, the lyrics make absolutely no sense, but the Americans always like to read into things, so let them read into it what they will.’”

In 2000 Bowie said of the song: “It’s another vaguely anecdotal piece about my feelings about myself and my brother. I was never quite sure what real position Terry had in my life, whether Terry was a real person or whether I was actually referring to another part of me.”

From start to finish, the album took two weeks to record and two to mix. Defries shopped the acetate to labels in New York, and got Bowie signed, with a $37,500 advance, to RCA, who were keen to hip up their roster beyond country music and Elvis.

Released on December 17, 1971, Hunky Dory was hailed by Melody Maker as “the most inventive piece of song writing to have appeared on record in a considerable time”. NME said it was “Bowie at his brilliant best”, while the New Yorker dubbed Bowie “the most intelligent person to have chosen rock music as his medium”. With a sleeve image suggesting a George Hurell portrait of Veronica Lake, Bowie seemed ready for his close-up.

Despite glowing reviews, first-quarter worldwide sales barely reached 5,000. Not that Bowie noticed. The man who’d sung ‘I’m much too fast to take that test’ was already back in the studio with his Velvets-meets-Iggy-in-outer-space masterplan, recording the album that within six months would transform him into a Martian messiah and worldwide glam rock superstar: Ziggy Stardust.

Because of Ziggy Stardust’s rise and all-encompassing effect on Bowie, Hunky Dory has remained in its shadow as the quiet, talented brother. But those close to Hunky Dory, while acknowledging its vital role in opening the space hatch and clearing the way for Ziggy, secretly prefer it as the stronger work.

Angie Bowie, divorced from David in 1978, now runs an electrical contracting company in Tucson. “David had interesting songs and important subjects to talk about,” she says, “and Hunky Dory shows that he had the kind of range and versatility as a writer to handle anything.”

Woody Woodmansey, who worked with Bowie up to 1973’s Aladdin Sane, says: “Hunky Dory was the album where David’s ability as a songwriter came through. It showed us all what it took to create quality products, how you had to tick all the boxes, from good song ideas, arrangements, rhythmically, sound-wise, emotionally and the rest. It was the start of David’s career, really.”

Bassist Trevor Bolder stayed with Bowie until 1973’s Pin-Ups. He has been with Uriah Heep since 1983. “It’s my favourite Bowie album, hands down,” he says. “I put it on constantly, and I will play it forever. a lot of musicians in the business that I’ve met were young kids when that album came out and it’s one of their favourites too. It’s got great songs, his singing is brilliant, and the lyrical content is superb. I don’t think you could’ve wished for a better album.”

Reflecting on its place in his five-decade-spanning catalogue, Bowie sees the album as the springboard to all his chameleonic changes.

“Hunky Dory gave me a fabulous groundswell. First, with the sense of ‘Wow, you can do anything!’ you can borrow the luggage of the past, you can amalgamate it with things that you’ve conceived could be in the future and you can set it in the now. Then, the record provided me, for the first time in my life, with an actual audience – I mean, people actually coming up to me and saying: ‘Good album, good songs.’ That hadn’t happened to me before. It was like, ‘ah, I’m getting it, I’m finding my feet. I’m starting to communicate what I want to do. now… what is it I want to do?’”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #156.