On the title track of his 1977 album Heroes, David Bowie sang the words: ‘I, I will be king’. He ruled over rock during his lifetime but, if anything, since his death from cancer, at the age of 69, on January 10, 2016, his dominance has seemed even more pronounced. As his former guitarist, John ‘Hutch’ Hutchinson, told Classic Rock, “The reaction to his death, for me, has been greater than for Elvis or Lennon.”

Bowie’s final album, Blackstar, was released two days before he died, and contained lyrical portents of his demise, which seemed to confirm a lifelong commitment to music as transgressive yet populist art. He had been recording, in one guise or another, for almost five decades – and ‘guise’ is the word for this musician, fashion innovator and provocateur, whose ever-shifting nature helped make him one of the biggest stars of the 1970s, and the natural heir to The Beatles.

He was born David Robert Jones in Brixton, South London on January 8, 1947, 12 years to the day after Elvis Presley. He was as revolutionary as his forebear, with his fluid sexuality, alien charisma, and ability to absorb various music styles to create something radical and new. After flirting with mod, musical hall, psychedelia and folk in the 60s, he seemed to come alive at the dawn of the new decade, blazing a trail with his outlandish glam image and startling yet commercial hybrid of Detroit rock and British pop. His performance on Top Of The Pops for the single Starman, during which he slung an arm around guitarist sidekick Mick Ronson’s shoulder, remains one of the most thrilling and pivotal moments in rock history.

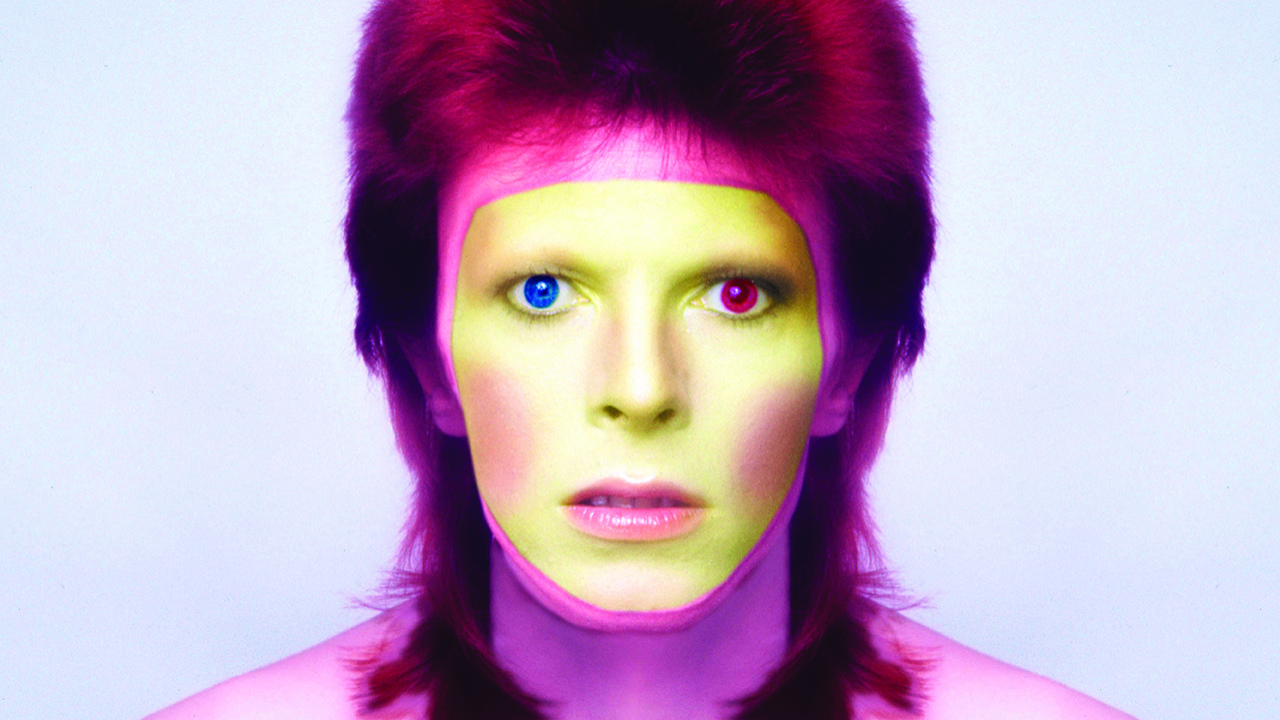

Moreover, his 12-album run from 1970’s The Man Who Sold The World to 1980’s Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) represents the greatest example of sustained creativity and dedication to progression and transformation in all of rock’n’roll. From neo-heavy metal and proto-goth, to glam, white soul, funk, ambient and electronic music and all points in between, Bowie’s golden age of albums covered all bases and invented several new ones. His many phases – Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke, his ‘Berlin period’ – gave countless imitators whole careers.

Bowie embodied the 70s, predicted the 80s, became a role model and technological innovator in the 90s, and spent much of his last decade as a reclusive, if ever-present, observer . He was an actor, a producer, a genuine modern-day Renaissance Man with an ability to surprise right up to his final two albums, 2013’s The Next Day and this year’s Blackstar. He was the ultimate rock star: bold and brilliant, cutting a swathe for others to follow. We will never see his like again.

JOHN ‘HUTCH’ HUTCHINSON was Bowie’s guitarist no fewer than four times between 1966 and 1973 – in The Buzz, Feathers, Bowie & Hutch and, briefly, The Spiders From Mars. Here he looks back on the man before the myth.

The first time I met David, it was at an audition for his new band. He was looking for a replacement for the Lower Third, who had all been sacked, and I was the first one he picked. He seemed very professional, organised and experienced. He looked skinny, more London than me – I was from Yorkshire. If you had to categorise him, he was a mod.

I played with Bowie and The Buzz for about six months. We played places like the California Ballroom in Dunstable, supporting people such as Jon Anderson’s band The Warriors. We also had a residency at the Marquee club.

David, as a frontman, used to dance a lot. Very energetic – like Jagger, only better. He had a great voice. He was protected by his manager, Ralph Horton, who treated him like a precious piece of china and kept him apart from me and the other guys in the band – although we all drove to gigs together in an old ambulance.

After The Buzz, I left for Canada. I came back in 1968, and David and his then-girlfriend Hermione Farthingale asked me to join Feathers, who were a folk group. David and I looked similar with our jumpers and soft haircuts. Feathers played the odd arts centre, and folk clubs where we didn’t get paid. We lasted a few months, and then when Hermione left we became Bowie & Hutch. We did a dozen tracks as demos – Bowie experts on bootlegs will have heard most of them. I was pleasantly surprised that I got a full credit for singing the ‘ground control to Major Tom’ part on the demo version of Space Oddity, which sometimes gets played on the radio. The first time David played me it I thought: “What an unusual song.” I thought it sounded like the Bee Gees. He was very inventive, although I thought it was a bit strange when he brought the Stylophone along. I remember him playing the song at Ralph McTell’s folk club in Bounds Green, with his curly perm and flares. We got some funny looks from the audience.

After Bowie & Hutch I went back up to Scarborough where I knew I could get a job. It was difficult leaving David. Ahmet Ertegun, the head of Atlantic Records, had wanted to sign us as a duo, I found out later.

I was working in the oil and gas industry when I got asked to join the Spiders From Mars as an auxiliary musician. I picked up the phone one day and it was Mick Ronson. He said: “Have you still got your Telecaster? Can you come to America with us?” David had decided to increase the size of his band and he wanted someone to play 12-string. I thought: “That’s the job for me.” One minute I was in a damp bedsit in Scarborough feeling sorry for myself, the next I was flying to New York.

The States was our first tour. I socialised a lot with David in those first few days. I remember him playing me Roxy Music in his hotel room, saying: “Have you heard these guys?” We went to Max’s Kansas City, and we saw Charlie Mingus in Greenwich Village.

None of the band was particularly druggy, but David lived a wilder life than any of the rest of us – he kept it under wraps. By the end of the tour I wasn’t spending much time with him – we’d just nod to each other at soundchecks, or he’d sometimes come to my room in the middle of the night to borrow a guitar.

We stirred the Americans up. In the south they objected to us. We got banned from playing Memphis for being too lewd. Bowie was doing the fellating the guitar thing with Mick – he was a showman.

The Spiders’ last show was the legendary one at Hammersmith Odeon in July 1973. We had no idea it was coming to an end. In fact Bowie’s manager, Tony DeFries, had told us to keep 1974 free “because you’re going to be out of the country a lot”. Anyway, Bowie told me: “Don’t start Rock’N’Roll Suicide before I give you the nod.” He wanted to make the announcement. I thought he wanted to thank everyone for a great tour.

I think RCA wanted to spend less money on the touring band. And maybe David had got tired of doing the same thing, night after night. It was perfectly legitimate, to achieve the effect he wanted. It was a piece of theatre, a sensational retirement. I certainly never held it against David.

I never got the chance to say goodbye. I did see him on the dancefloor at a party at the Café Royal after the show. All the stars were there. I was dancing with Princess Nina of Nina & Frederik, these huge folk hitmakers; David was dancing with Bianca Jagger. He nodded and said: “You alright?” I said: “Yeah, I’m alright.” That was the last time I saw him.

I went to see him play on the Reality tour in Manchester in 2003. I took my wife and daughter. We were going to go backstage, but we got prioritised out by Debbie Harry and her entourage.

I did get an email from him the other week, a Christmas one. It was as if nothing in the world was wrong. It was cryptic, but humorous. I think David knew I was still his friend. We just happened to be separated by his fame. And the Atlantic Ocean.

His death came as a terrible shock. But he must have known it was coming, especially seeing the videos to some of the tracks on Blackstar. They are very much in keeping with the David that I knew: very practical, artistic and determined.

He was probably the icon of our age. He helped people, and changed their lives. The reaction to his death has, for me, been greater than for Elvis or Lennon. It’s been phenomenal. I can’t help thinking he’d have been delighted, that he’d have wanted it – to make his mark, right at the end. I’m chuffed for him.

For RICK WAKEMAN it was a toss-up between joining Yes or the Spiders From Mars. It would be the start of a friendship with Bowie that lasted 40 years.

The first met David when I played Mellotron on the Space Oddity single in 1969, which was such a privilege. I came home that night and told friends I’d just worked on one of the best songs I’d ever been a part of. I also did some piano on Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud and Memories Of A Free Festival, from his second album, which came out the same year.

David then invited me to his house in Beckenham to hear the tracks that became the Hunky Dory album, and those songs were so great that I did that album with him. We became mates and he gave me great freedom when it came to the parts he wanted me to play.

I remember it as a period of tremendous fun. So much so that when he formed the Spiders From Mars, I met up with him and Mick Ronson in Hampstead and David asked me to join. It was a big honour. But how about this for a coincidence: on that very same day, Yes had asked me to join them.

What a decision. It was like being asked to sign for Chelsea or for Manchester City. I ended up choosing Yes. I had already worked with David for a while, and it was pleasurable. I admired him greatly and loved him to bits. He’s probably the most influential person I ever worked with. But of course we’d have worked on David’s stuff alone. Great as it was, there was a limit on how far I could have gone with him, whereas with Yes there was a chance of playing my own music and being part of a bona fide group. So I went to see David and that’s exactly what I told him. His response was that it was absolutely the right decision in every respect.

A few years later, in 1976, we became neighbours in Montreux, Switzerland, and we often met up for drinks, so that subject – me turning him down and joining Yes – came up from time to time. David said I was correct in my choice – two or three years later he changed the line-up of the Spiders anyway.

I worked with him again in the mid-1980s. He called and asked if I would play on Absolute Beginners, for the film of the same name. He said: “Do you fancy doing this for old times’ sake? I need some Rachmaninov-style piano.” We sat in the pub and reminisced for a couple of hours, I did the track and that was it.

He was one person on stage and another off stage – sometimes he was more than one person on stage. But I believe I got to know the real David Bowie, because when I first knew him he was still absorbing all of the influences that made him into David. I consider myself lucky that I knew him during that period. Later on, in the Montreux days, we would meet in a place called the Museum Club and be there for hours and hours, chatting about a variety of different subjects.

Obviously I followed his career every step of the way. He never stood still, he was his own man in every respect. David was utterly priceless. He could turn out to be the most influential musician, artist or performer – call him what you like – of my generation, and quite possibly of any other to come.

I’ve so many anecdotes about David. Among my favourites comes from the time I ran a little folk club in Acton, west London, called Booze Droop, back in ’69. We owed the landlord… crikey, it was about 40 quid, a fortune in those days; I only earned 18 quid a week from the Strawbs.

I knew that David had been a folk singer as Davy Jones and after we’d done Space Oddity. I was telling him about the nightmares we were having. He said: ‘I’ll come and do a night for you. It’d be fun to dust down the acoustic guitar. I haven’t done that for years.” When I asked him about a fee, he said: “Oh, just give us a fiver.”

So I took out a big advert in the Melody Maker – which I couldn’t afford – and we put up posters all around Acton. What I hadn’t counted on was a particular trick that the folk clubs were pulling at the time. They’d advertise a huge name that they hadn’t even booked. The punters would get inside and the announcer would say: “We’re sorry, Fairport Convention can’t make it tonight. But we have got Peter And The Snotbags.” By then it was too late, the club had your money.

So the big night comes. David Bowie at Booze Droop… and 12 people turned up, because everyone thought it was a con. Word spread like wildfire, and as he finished his last song people began cramming in through the doors. But they were too late. David thought it was hilarious.

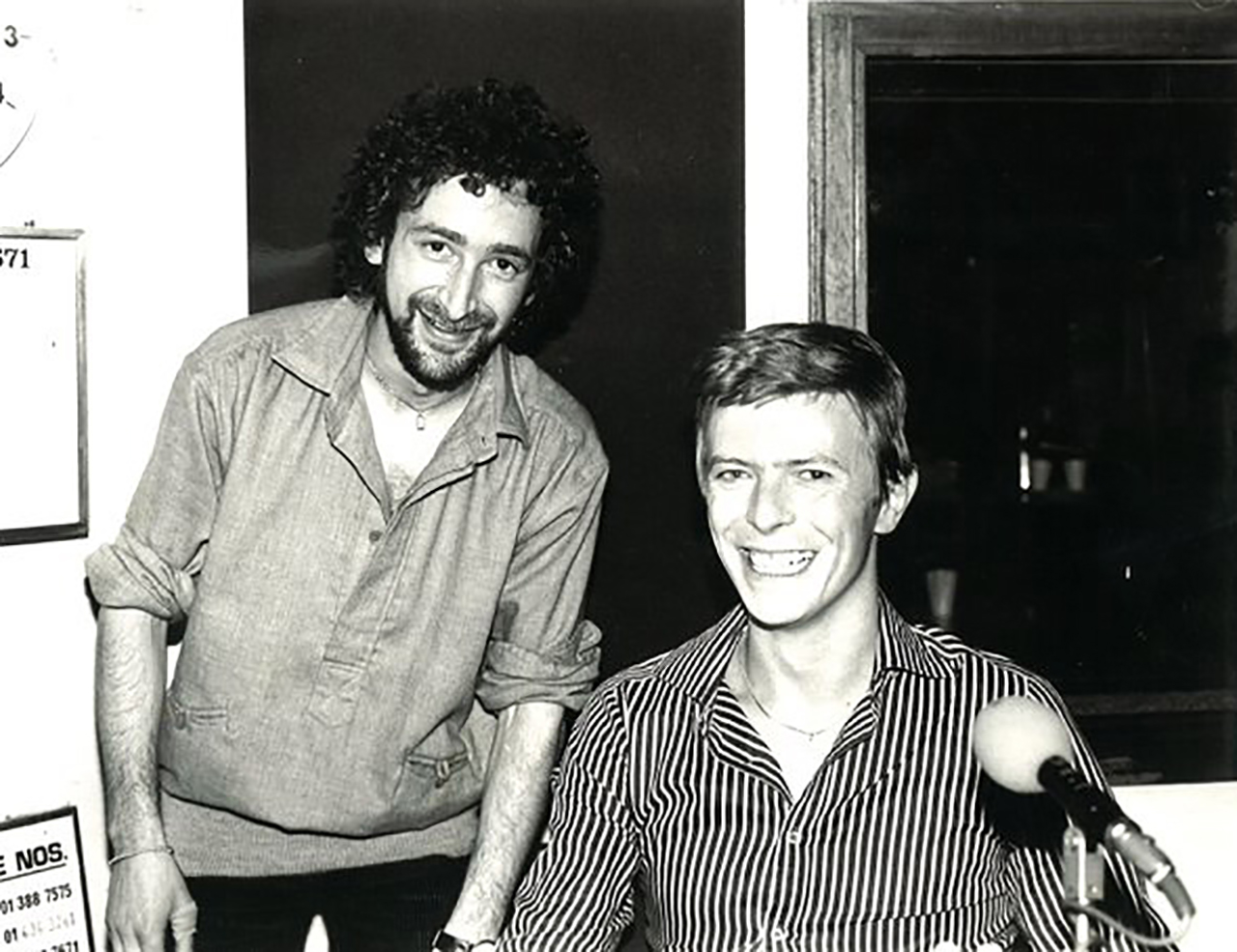

The Classic Rock Radio Show’s NICKY HORNE interviewed Bowie several times in the 1970s. And he’s the only DJ who the singer nearly got fired.

My first encounter with David Bowie was in 1972 as a cub reporter for Radio 1. Every week I would go to Top Of The Pops and knock on dressing-room doors. For each interview that was broadcast I received the princely sum of seven pounds, seven and sixpence.

So I was at Television Centre for the famous clip for Starman, which had the homo-erotic incident with Mick Ronson. It was the first time that many people had actually seen Bowie. I spoke to David and Mick together in their dressing room, and also witnessed the rehearsal when Bowie leant his arm nonchalantly on Mick’s shoulder, so it was all pre-planned.

A couple of years later I was working at Capital Radio, and David’s label, RCA, asked whether I would like to go to Toronto for the Diamond Dogs tour. My programme director was a bit jealous, but he eventually said yes. That night on their air, really stupidly, I announced that the following week I was going to Canada to bring back an exclusive interview with David Bowie.

It had all seemed to be going well. A stretch limousine took me to a five-star hotel suite. But I was told David was not in a good way and wouldn’t be able to do the interview the following day as planned. It might, they said, happen the day after. That didn’t happen either.

The gig was fucking amazing, just astonishing. But the morning afterwards, word came back that David had headed off to the next show. I was with the head of RCA Promotions, and even he couldn’t get anywhere near David. So I returned to London with my tail between my legs. When my director learned what had happened he went apeshit. Partly through jealousy, I believe, but also because I’d said on air that it was going to happen. I’d made the station look bad, so he came close to firing me.

A couple of weeks later I was at home and the phone rang. “Is that Nicky? This is David.” “David who?” “David Bowie.” I told whoever it was to fuck off, but it really was David Bowie. He’d heard that I’d got into trouble over Toronto, and promised that next time he was in London he’d give me an exclusive interview. So about a month afterwards he came in and spoke to the listeners on the phone. The programme was so good it actually ran overtime.

We did several other interviews. And after a particularly good one, David asked whether I did ‘private stuff’ – projects away from the station – because he had a new album coming out, it was to be called Low, and he wanted to try a different kind of promotion. The idea was to get together lots of his fans in a room, play them the album, and he would field questions. This was because Low was a different album for him, so he preferred to do just one interview as a promotional tool, and to supply it to radio stations around the world.

And that’s what happened. He explained the mechanisms behind Low, why it was less accessible than the others and sounded the way it did. It was a great success. Some of the questions were really dumb and others extremely intelligent, but David handled them all in a classy, friendly manner. It was broadcast by Capitol Radio, and also became an album called Conversations With David Bowie.

What amused and amazed me the most was that David and his producer Tony Visconti, who had been so knowledgeable about recording studios, yet were gobsmacked when they saw me working with quarter-inch tape, editing and dubbing from one tape to another. These were very simple techniques in radio, but I found it amazing to have David Bowie asking questions about how a radio show was produced.

In 1999, I also did a live webcast with him – one of the first of its type, which became the second-most popular of its era, behind one that Tony Blair had done. It’s another example of David staying ahead of the game.

Listening again to the new album Blackstar now that he’s gone, a track like Lazarus takes on a completely new meaning. It’s so profound.

You can talk all day long about David being a shapeshifter, from Tin Machine to the Thin White Duke. But for me, I will never forget that he called me up when I’d got into the shit. He was a fascinating, warm, incredibly intelligent guy – in fact, along with John Lennon the only other person I interviewed with a ‘not quite of this world’ quality about them.