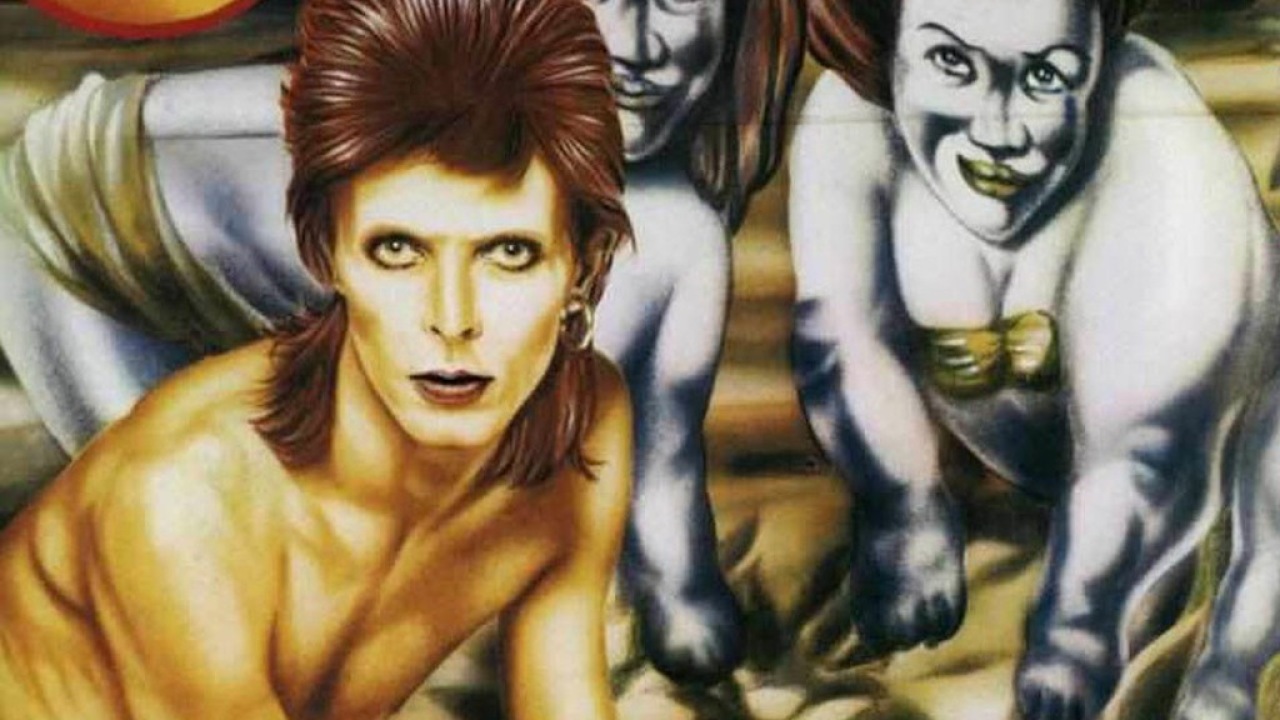

Once deemed a pretentious grand folly by the less imaginative, Bowie’s first real post-Spiders album is now recognised as a moody masterpiece of visionary rock. Released on this day (April 24th) in 1974, it gave him another UK number one and broke him in the States, reaching number five there as he toured in Cracked Actor mode.

As Bowie biographer David Buckley has written, it is “cinematic in scope, breathtakingly audacious in execution.” It also brought the curtain down on Glam’s first wave: its spooky, stuttering, shuddering sci-fi apocalypse was the final word in flamboyant melodrama, and Bowie was already dreaming of his plastic soul epiphany.

Liberated as, effectively, a solo artist again, he wrote, arranged and produced, playing distorted guitar and sax startlingly well. Tony Visconti came in for mixing and the string arrangements on “1984”. It was that Orwell novel which inspired the album, albeit in a nebulous way. Bowie – always an avid, impressionable reader - had intended a 1984 stage musical, but Orwell’s widow denied him the rights. He thus found himself with a group of songs discussing totalitarianism, all dressed up with nowhere to go. So he created his own futuristic nightmare-scape, Hunger City, and peopled it with his lyrics of disenchanted, post-nuclear looters and lovers. As with many Bowie “concepts” – see also Ziggy Stardust – it doesn’t quite hang together narratively. And it doesn’t matter, because the songs are so powerful.

He’d also recently met William Burroughs for the first time, and his book The Wild Boys, with its gangs of feral youths rustling through sexualised scenes of urban decay, was another key influence. As was Burroughs’ use of the “cut-up” technique, the words whirling and spiralling through chants, shrieks and the singer’s phenomenal croon.

Future Legend sets the scene and tone, Bowie’s chilling voiceover warning us of corpses, red mutant eyes, giant fleas and rats and “ten thousand peoploids” split into small tribes in the shadow of sterile skyscrapers. Then we lurch into the title track, at heart a bog-standard rock piece which in ’74 perhaps reassured listeners there was nothing to get too worried about here in Love Me Avenue. For now, this wasn’t genocide, this was rock’n’roll. And then, the double twist. Because then “Sweet Thing/Candidate/Sweet Thing (Reprise)” saunters in, all artful lighting and matinee-idol insouciance, to deliver Bowie’s greatest ever nine minutes. Nicholas Pegg in The Complete David Bowie hails it as “a stunningly bleak glimpse into the abyss…(which) remains one of the most comprehensively imagined and dramatically performed of all Bowie’s recordings”. It’s indeed a performance, a movie: The Wanderers in Metropolis,+ featuring Brecht, Charles Manson and Cassius Clay. So intimate and nuanced is Bowie’s voice (until it explodes) that we’re anxiously pacing the starving, needy streets along with his character. The triptych shifts from baroque ballad to ultra-decadent recitation (Candidate, with its spitfire rhyming, isn’t far off being the first rap record) then back to a snowstorm of romantic yearning. Throughout, lines like “we’ll buy some drugs and watch a band” and “when it’s good it’s really good and when it’s bad I go to pieces” offer themselves up as generational touchstones, infinitely more significant to Seventies British teens than anything Dylan or Lennon had coined.

If that was the centrepiece to listen to at home with the lights out, Rebel Rebel (that riff!) was the Stones-trumping, gender-bending floor-filler. Side Two then upped the ante on Gothic gloom and noir with Rock’n’Roll With Me and We Are The Dead, took Isaac Hayes’ Shaft into dystopia with 1984 (which, musically, foreshadowed the Young Americans album) and addressed Orwell’s themes both head-on and tangentially in Big Brother. Its hovering sonic segue into the exhilarating Chant Of The Ever-Circling Skeletal Family is one of the all-time great rock moments, of which this album has an abundance.

Diamond Dogs clarified that Bowie could outlive Ziggy and Aladdin and confirmed that he was bigger than either. More ambitious, daring, and ridiculously gifted: as a singer, as a musician, as an ideas man. As a star, he was set on another plane from his peers by its strangely affecting mysteries. That fact established, he elected to burn it all down and go disco. Nobody foresaw then that he had so many more restless chameleons within him.

In 2014, Diamond Dogs still prickles with scale and ingenuity. With hindsight, it wasn’t just the last great flourish of Glam Rock, but the beginning of something else: the sound of an artist surprising himself by how far and wide and deep he was ready to go. “I’ve found a door”, he sang, “which lets me out”. If only today’s rock’n’roll stars would look behind that door once in a while.[](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BdobGDTdJfo)