When Rainbowman met Gangsterman: The story of the gig that invented glam rock

The crowd at 1970’s Atomic Sunrise Festival in London wasn't much interested David Bowie’s new band Hype, with their lurex outfits and make-up, but one onlooker was: Marc Bolan

We’re having a moment here. It’s March 25, 1971 and this Thursday’s episode of Top Of The Pops, the BBC’s flagship chart show, has reached its finale. So far we’ve had Andy Williams, Gilbert O’Sullivan, Fleetwood Mac, even the Plastic Ono Band. Now it’s time for this week’s No1. Mungo Jerry’s Baby Jump has been swatted from its perch by Hot Love, an insidious little boogie from T.Rex that will stay put for the next month and a half.

It’s a great song all right. And with his satin and curls, a Gibson Les Paul slung across his chest, Marc Bolan cuts a dramatic figure. The most striking thing, however, is the splash of glitter on each cheek. The work of T.Rex publicist Chelita Secunda, who’s already applied a thin caking of mascara to Bolan’s eyes, it fires the imagination of hordes of young viewers. Bolan claims he prettied himself up on the spur of the moment, just for laughs. But his next gig finds him greeted by hundreds of adoring teenage fans, all decked out in various degrees of glitteration. There was no escaping it: Bolan had introduced glam rock to the masses.

But it wasn’t quite as spontaneous as that. A year earlier, Bolan had been in the audience at a London Roundhouse show by Hype, fronted by David Bowie. This was a gig that flew directly into the wind of the times. One that brought colour, playfulness and a hint of self-mythology into what was an overwhelmingly monochrome era.

Then known as the curly-haired creator of Space Oddity, a sci-fi tune that had landed him a surprise hit in 1969, Bowie was looking for a new direction. Everything around him seemed drab and overly serious. Denim was the unofficial uniform of the music fraternity, be it worn by earnest singer-songwriters with acoustic guitars or tribes of unsmiling prog bands. Where was the flash? Where was the fun?

“At that point in time, rock seemed to have wandered into some kind of denim hell,” Bowie recalled in 2003’s Moonage Daydream, photographer Mick Rock’s visual account of the rise of Ziggy Stardust. “Street life was long hair, beards, leftover beads from the 60s and, God forbid, flares were still evident. In fact, all was rather dull attitudinising with none of the burning ideals of the 60s.”

Bowie and his soon-to-be wife Angie Barnett were sparked into action by photographer Ray Stevenson. A comic-book nut and regular visitor to the couple’s base at Haddon Hall in Beckenham, South London, Stevenson recalled an evening spent talking about “supermen and superstars”. Next time he called, Bowie and Barnett were busy with a sewing machine. The idea of flamboyant stage gear had taken hold.

In February 1970, Bowie had brought in guitarist Mick Ronson, largely on the recommendation of drummer John Cambridge, for a new band that also included his producer Tony Visconti on bass. A phone call to Bowie’s manager Ken Pitt sparked a discussion over what to call themselves, with a chance remark – “The whole thing is just one big hype” – providing a name that seemed to suit. “Bowie used to think that everything was hype,” recalls Cambridge today. “It was all shit, in other words. So he said we should just go with it.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

What happened next is still open to conjecture. Pick up any Bowie biography and it’ll tell you that the band’s live debut, supporting Fat Mattress at the Roundhouse, Chalk Farm, on February 22, marked the first occasion that they wore costumes. Visconti even says so in his autobiography, Bowie, Bolan And The Brooklyn Boy. Yet Cambridge, who kept a diary, insists they didn’t dress up until they returned to the Roundhouse a fortnight or so later.

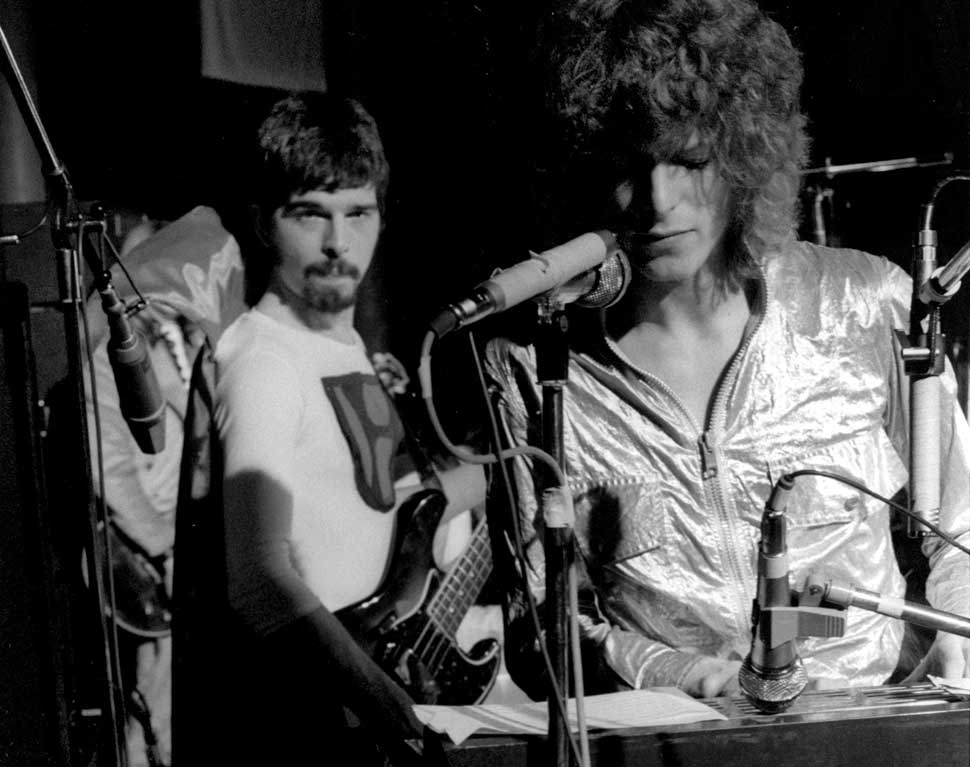

With Barnett and Visconti’s girlfriend Liz Hartley as seamstresses, each member had been assigned the role of a spoof superhero. Bowie had a blue cape, Lurex tights and thigh boots in his guise as Rainbowman. Visconti, in green cape and white leotard, a giant ‘H’ emblazoned on his chest, was the Superman-styled Hypeman. Ronson borrowed Bowie’s suit from a recent awards show – the singer had been voted Disc And Music Echo’s ‘Brightest Hope For 1970’ – and became Gangsterman. While Cambridge, in frilly shirt and 10-gallon stetson, was Cowboyman.

It was a transition that wasn’t merely sartorial. Positing himself as a psychedelic folkie, Bowie’s previous work had been mostly acoustic. Now he was fronting an electrified rock’n’roll band. They didn’t go down well at all. Fans of the headline act made no secret of the fact they didn’t go in for post-hippie songs like Memory Of A Free Festival or the Velvet Underground’s I’m Waiting For The Man.

Bowie’s new band weren’t actually billed as Hype at the Roundhouse. It wasn’t until they played Basildon Arts Lab, six days later, that he finally decided on using the name, if not the clothes. Though for their next major engagement, back at Chalk Farm on March 11, they most definitely did break out the faux-superhero gear.

Appearing as part of the venue’s Atomic Sunrise Festival – Seven Nights Of Celebration, organised by the Living Theatre collective – Hype took their place alongside Quintessence, Graham Bond, Hawkwind, Third Ear Band, Kevin Ayers and Arthur Brown.

“Danae Brook, who was associated with the Living Theatre, wanted to do this mad week at the Roundhouse,” recalls DJ and scenester Jeff Dexter. “So she and I organised it. I booked all the bands and Allan King Associates decided to film it all. They had two or three cameramen at the festival.”

Hawkwind’s Nik Turner was there for the duration. “I knew the people who ran the venue,” he says, “so they’d let me come and go. It was all pretty casual and LSD was the drug of choice. People were either giving it away or spiking each other with it. The acts were really cool and everything was very mystical and magical. I remember David Bowie playing with his guys, all dressed as superheroes.”

Bowie headlined on the Wednesday night. Opening the show that evening were Genesis, then a relatively unknown band, testing out songs from their soon-to-be-recorded second album, Trespass.

“We were trawling around the country,” recalls ex-guitarist Anthony Phillips, “and the festival did have the feel of being something pretty big. I don’t think there was a large audience, though. I would’ve thought that Bowie might’ve pulled in a bigger crowd, because he’d had a hit with Space Oddity. But he was nowhere near the Bowie that we all know. We weren’t thinking superstar, we were thinking quirky guy who’d had that hit.”

Phillips’ memory of the night remains fuzzy, but Genesis keyboard player Tony Banks has a sharper recollection. “I remember Bowie quite well,” he offers, “because I was a big fan already. I’d bought an early single of his, Can’t Help Thinking About Me [1966, with The Lower Third]. So I’d followed him since then and Space Oddity had brought him into the public eye. He and the band were all wearing costumes, and I hadn’t really seen that kind of thing before. It was pretty interesting.”

Not every Hype member was keen on the get-up, though. Dressing up was one thing, but cosmetics was another. “Both me and Mick [Ronson] went: ‘There’s no way I’m doing that!’” laughs Cambridge. “Cowboys don’t wear make-up. But compared to Visconti, in his cape and tights, me and Mick got away lightly in the end.”

They certainly looked the part. Bowie’s outfit consisted of a silver jacket with metallic belt, silver tights, billowy satin cape and thigh-high leather boots. Visconti was similarly spacey in his Hypeman ensemble, while Ronson’s borrowed Gangsterman suit was given added zing by his appropriation of a loud tie with giant dots.

John Cambridge recalls how his own outfit came together: “I remember meeting Visconti at his offices on Oxford Street one day. We were crossing the road together and saw this cowboy hat in a store. He just went in and bought it. I’ve still got it actually, it’s been up in the loft.”

The setlist that night included Bowie originals Memory Of A Free Festival and The Supermen. The latter, with its allusions to Nietzsche and HP Lovecraft, was soon to find a home on The Man Who Sold The World, his third album, issued later in the year. Among the covers played were I’m Waiting For The Man and John Lennon’s Instant Karma.

“We’d always do a couple of covers,” explains Cambridge. “We’d play Canned Heat Let’s Work Together, which was in the charts in 1970. I remember Bowie saying to me, ‘I really like that lyric, “Together we’ll stand/Divided we’ll fall”. I wish I’d written a song like that.’ I said, ‘You know it’s in another song as well? Brotherhood Of Man have got a single out called United We Stand.’ He went, ‘They haven’t! Oh shit!’”

All parties remember the crowd as convivial, if largely indifferent. Cambridge likens it to audience footage of the Woodstock festival, albeit on a micro scale, full of people in headbands, waving their arms about, “stoned out of their heads”.

But there was at least one attendee who was paying full attention: Marc Bolan. Bowie and Visconti had no idea that he was even there. It was only much later, when going through Ray Stevenson’s shots of the gig at the back end of the 70s, that the discovery was made.

“There is a photo somewhere and Marc Bolan is at the very front of the stage,” confirms Cambridge. “The photo is taken from the back of us, looking out at the audience, and Marc’s there. This was when he was still doing Tyrannosaurus Rex. Woolworths used to sell these plastic shields, like copies of armour, and he had it strapped to the front of him, just to be different. You can see him looking up at Bowie with all this make-up on and his Lurex tights. And his eyes are saying: ‘Ahh, I’m gonna have a bit of that!’ So he took it on. When it comes to this big debate about whether it was Marc Bolan or Bowie who started glam rock, it was definitely Bowie.”

Visconti has credited both Bowie and Bolan for having “simultaneously kind of invented” the glitter movement. Though in his autobiography he states that that Roundhouse gig “will always be the very first night of glam rock”. The most hyperbolic assessment, however, belongs to Mick Rock: “If David Bowie was the Jesus Christ of glam. Then Marc Bolan was John the Baptist!”

Bowie, himself, has mixed feelings about that first night of glam. “It was really just the most depressing night of our lives,” he recalled later. “We thought we were kind of smart, but nobody even looked at the stage. So it was all to no avail. But that was a wonderful show in as much as I knew that theatre was for me after that.”

It certainly wasn’t a new idea. Little Richard had camped it up in sequinned vest and mascara, Elvis and Billy Fury had their gold suits, the Rolling Stones and The Kinks had flounced around London like foppish Edwardian dandies. But what was fascinating about Bowie was that he was beginning to take it further.

Dressing up at the Roundhouse was the first manifestation of the rock star as a projection; adopt a fictional persona and play it out on stage. Design your own future, then will it into being. "So inviting, so enticing to play the part," he would later sing on Star. "I could play the wild mutation as a rock’n’roll star."

Ziggy was still a couple of years away, but the seed was sown.

Hype wasn’t designed to last. Two nights later, after a show at Sunderland’s Locarno Ballroom, they ditched the costumes. Bowie carried on with the name until the end of March, when John Cambridge played his final gig at the Star Hotel in Croydon. A week later, he was replaced by another ex-member of The Rats, Woody Woodmansey. Cambridge had at least played a part in the birth of Ziggy Stardust, which in turn would signal the arrival of Bowie the superstar.

“I always say that I wasn’t in the Spiders,” he says, “but I helped weave the web.”

The reconstituted version of Hype backed Bowie on sessions for The Man Who Sold The World in April and May 1970. Though by the time it was in the can, he’d acquired hard-nosed businessman Tony Defries as manager. One of his first conditions was to drop the band. “Defries only saw David as the star,” says Visconti. Ronson and Woodmansey, for the time being at least, also headed home to Hull.

The footage from the Roundhouse lay on a shelf for two decades after Allan King Associates went bust. In 1990, it was bought by producer Adrian Everett, though the original soundtrack had long been lost. An edited version, Atomic Sunrise Festival 1970, was finally screened in the Roundhouse’s Studio Theatre on March 11, 2013, exactly 33 years since Bowie and Hype rocked the place.

It remains a defining moment in the trajectory of Bowie and, by extension, 70s rock. Just around the corner were T. Rex, Roxy Music, Sweet and a host of glittery glam icons. Plus, of course, Ziggy. “I just stopped after that performance [at the Roundhouse],” Bowie told NME years later, “because I knew it was right. I knew it was what I wanted to do and I knew it was what people would want eventually.”

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.