David Bowie's Changes: the story behind the song

How a young David Bowie’s artistic manifesto was captured in the three and a half perfect minutes of Changes

In the spring of 1971, when David Bowie wrote the now classic line ‘Turn and face the strange’, he created a mission statement for the next decade of his career. At the age of 24, seven years into that career, three albums and ‘a million dead end streets’ behind him, Bowie had been brooding on the sidelines as friendly rivals Marc Bolan and Elton John started to find stardom.

Determined not to be left behind, he pooled his creative strengths and began writing songs that were “more immediate”.

“In the early seventies it really started to all come together for me as to what it was that I liked doing,” Bowie told me in 2003. “After I came back from my first trip to America, I had a new perception of songwriting, and it was about a collision of musical styles. I found that I couldn’t easily adopt brand loyalty, or genre loyalty; I wasn’t an R&B artist, I wasn’t a folk artist, and I didn’t see the point any more in trying to be that purist about it.

"What my true style was is that I loved the idea of putting Little Richard with Jacques Brel and the Velvet Underground backing them. What would that sound like? Nobody was doing that. At least not in the same way."

Changes began, he once said, as “a parody of a nightclub song”. But it quickly became one of his new hybrids, fusing cocktail jazz, boogie woogie and beat poetry to a Beatlesque chorus.

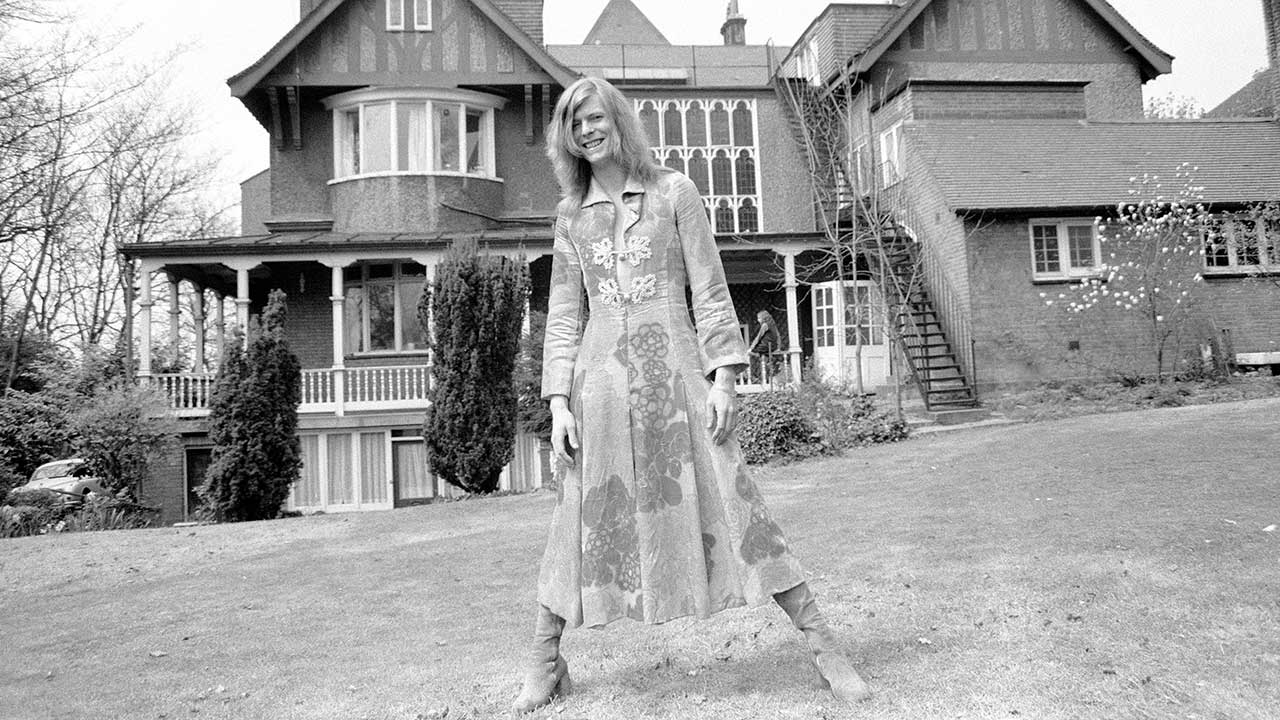

Significantly, as Bowie worked on the song – and all the material for the Hunky Dory album – he would often swap his usual instrument, a Harptone 12-string acoustic guitar, for the ancient grand piano at Haddon Hall where he lived.

“He loved that piano,” Angie Bowie told me. “David was a fantastic musician, because his approach was not studied, it was by ear. He had an ability to pluck a song from those first moments when he played with an instrument. Writing on the piano opened up his possibilities, because of its association with so many kinds of music – classical, cabaret, every style.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Listening to Bowie’s home demo of Changes, the song is all there, although his playing is a bit plodding. That’s why he brought in session ace Rick Wakeman to play piano and embellish and add more of a nuanced touch to the recording.

“David knew what he wanted to do,” Wakeman tells Classic Rock. “He knew how the music needed to be and he would pick musicians that he felt could achieve what it was he was after. I went to his house, and he had his guitar and he played all of the songs, and every single one was a winner.

"I took some manuscript paper and I was writing stuff down, and I stopped and said: ‘Do you know what you’ve got here? This is the finest collection of songs, and I tell you what, I don’t have any money but if I did I would put it all on saying that this particular record – which he already told me was going to be called Hunky Dory – will still be around and important long after you and I are gone.’

"And he laughed. I said: ‘I’m serious.’ He gave me total freedom to play what I liked, really. The vamping bit in Changes was his idea because that’s how he wrote the song, so that’s how it stayed. Sometimes when there’s something simplistic, if it works then keep it.”

Sessions for Hunky Dory at London’s Trident Studios ran through June and July 1971. Bowie, his musicians and producer Ken Scott worked from two p.m. to midnight, Monday to Saturday, with quick breaks for tea, sandwiches and the occasional bottle of wine. There was a sense of excitement on the sessions, fuelled by Bowie’s new material.

“Honestly, I didn’t think he had these songs in him,” recalled drummer Woody Woodmansey. “They were more structured. He’d obviously focused more as a writer, yet he’d managed to keep his unique approach, especially lyrically, while streamlining everything.” “

Hunky Dory was the first recording session I ever did in my life, and just to be in a studio was amazing,” the late bassist Trevor Bolder said. “Our approach was very off-the-top-or-our-heads. We’d go in, David would play us a song – often one we hadn’t heard – we’d run through it once and then take it. No time to think about what you’re going to play, you’d have to do it there and then. In some respects it’s nerve-racking, but it gives a certain feel. If you play a song too many times in the studio it can become stale, and I think David wanted to capture the energy of it being on the edge.”

“There was incredible pressure in getting a track recorded right,” Woodmansey agreed. “David didn’t like doing more than three takes to get it. Nearly every track I recorded with David was first, second or third take, usually second. He knew when a take was right.”

Changes was released as a single in January 1972, but failed to chart in the UK, and in the US it made it only to No.66. But it became a staple of FM radio, and in Bowie’s live sets, evolving through different arrangements as his stylistic calling card. As the lyric says, he was always ‘much too fast to take the test’ of being pigeonholed.

The song, which has become an anthem of youthful freedom, has been covered by several artists, perhaps most creatively by Seu Jorge in Wes Anderson’s film The Life Aquatic. It was also a preamble to John Hughes’s teen movie The Breakfast Club.

Did Bowie know back in 1971 that he was making a career-defining single?

Putting it in context of the album that it kicked off, he told me: “Hunky Dory gave me a fabulous groundswell. First with the sense of: ‘Wow, you can do anything.’ You can borrow the luggage of the past, you can amalgamate it with things that you’ve conceived could be in the future, and you can set it in the now.

"Then the record provided me, for the first time in my life, with an actual audience – I mean people actually coming up to me and saying: ‘Good album, good songs.’ That hadn’t happened to me before.

"It was like: ‘Ah, I’m getting it. I’m finding my feet. I’m starting to communicate what I want to do. Now… what is it I want to do?’”

Bill DeMain is a correspondent for BBC Glasgow, a regular contributor to MOJO, Classic Rock and Mental Floss, and the author of six books, including the best-selling Sgt. Pepper At 50. He is also an acclaimed musician and songwriter who's written for artists including Marshall Crenshaw, Teddy Thompson and Kim Richey. His songs have appeared in TV shows such as Private Practice and Sons of Anarchy. In 2013, he started Walkin' Nashville, a music history tour that's been the #1 rated activity on Trip Advisor. An avid bird-watcher, he also makes bird cards and prints.