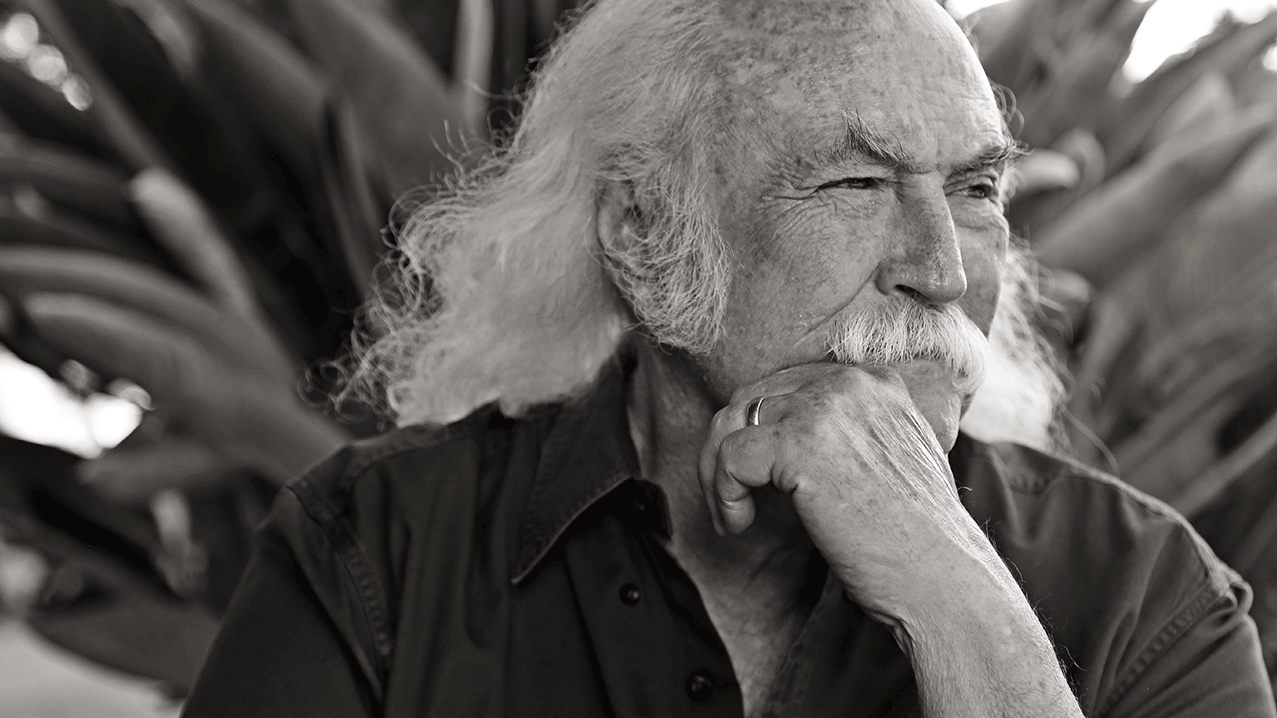

With Crosby, Stills & Nash on permanent hiatus, David Crosby is enjoying something of a solo career renaissance. Obviously, a formidable reputation precedes him, so it shouldn’t really come as any surprise that this co-founder of The Byrds, who either wrote or co-wrote Eight Miles High, Wooden Ships, Teach Your Children, Almost Cut My Hair and many more is still capable of producing exceptional work, especially in today’s early-60s echoing troubled times.

Nevertheless, it’s impressive that his three most recent recordings, made in close collaboration with his son James Raymond (2014’s Croz, last year’s acoustic Lighthouse and his latest Sky Trails album), sit comfortably alongside his very best.

Kicking back in his California home, Crosby laughs loud and long when I observe that he retains possession of a voice of such clarity that women appear to find it impossible to resist, spluttering: “Let that be the headline for the piece, you silver-tongued devil. I want that one out there!”

The Sky Trails song Capitol is laced with a cynicism that seems to extend to politicians of all political leanings. Is corruption an essential element within all those who seek political office, or only those who attain it?

Corruption’s endemic in politics. There are exceptions. The law of averages – the law I respect the most – tells me there are occasional politicians who are honest and trying to serve the people that elected them, but most are blatantly corrupt. They’re pretty scummy people.

In the United States right now it’s as if we’re a failed country. We’ve stopped being anything other than a bad joke. If I come to Europe I’m going to sew a maple leaf on my shoulder!

What do you make of the rise of the political right in the wake of Donald Trump’s ascendancy into presidential office?

It’s scary because it’s happening in a lot of places. It’s happening in Poland, they tried to drag the UK to the right, they tried it in France and Holland without success. You see it a lot and it’s been encouraged by the rise of right-wing fanaticism in this country, which has been unquestionably encouraged by this asshole we have for a President. Please quote me!

Many of the songs with which you were involved during the first decade of your career are evocative of a time when change was swift, protest achieved much in the field of civil rights, the anti‑war movement shortened the Vietnam war and environmental concerns were being voiced. The future looked incredibly bright. So what went wrong?

The Democratic Party failed us. The Republican Party stooped to levels even we, who felt them capable of really awful stuff, couldn’t believe. The problem in the United States always goes back to money. Corporations spend billions of dollars buying elections and own the people they gave the money to. Then they call up and say: “Quarterly report’s down, we need a nice little war. Why don’t you send some people back to Afghanistan?” And that’s a very bad situation. The United States is, at best, in a lot of trouble.

Do these troubled times add fuel to your fire? Do you find that you’re writing more?

I’m certainly trying to. I’ve been saying for a while that we need a song for our times. A song as strong as Ohio or We Shall Overcome. A song for our people out there in the street. And we don’t have it yet. I’m trying to write it myself, and trying to get anybody else to write it. I don’t care where it comes from, I just care that there is one.

Do you think the optimism of the 1960s has a place in today’s cynical society?

Yes. You need to have optimism and hope in order to function. I have to, anyway. Okay, this guy’s a terrible president and we’ve got terrible people showing up doing awful things, but it’s making us look at them. Racism was always here in the United States of America. We just weren’t looking at it. Now they are marching down the street with torches in their hands, and it’s real. It’s ugly and it’s not fun, but America needs to look at this so we can deal with it. We can’t deal with it if we pretend it isn’t there.

During the early eighties you were in the grip of a debilitating cocaine addiction. At that point, freebasing seemed to have reached epidemic proportions. Did its prevalence within the rock community come in the wake of the apparent death of sixties idealism?

I don’t know if they were linked, but certainly the advance of the drug culture and the debauch of idealism happened at roughly the same pace and would seem to be connected. I don’t know if you can prove the causality, but they’re definitely connected. We didn’t know the drugs were going to get us addicted, sap our will, ruin our lives, pick up our families and destroy us, but it’s exactly what they did. It happened at the same time our leaders were getting shot – King, Kennedy. There were a lot of factors in losing, or damaging, that idealism, and drugs was only one of them.

Drugs messed us up and did great harm, and we lost a lot of people to them, but I don’t think it’s as simple as the one caused the other. There are a whole multiplicity of variables there affecting it.

One event that’s emblematic of those changing times was the assassination of John Lennon, which compelled you to arm yourself for self‑preservation. It was a decision that saw you fall foul of the law more than once. Where do you stand now on the right to bear arms?

I grew up in a different time. Where I grew up we raised lemons and avocados, and when you turned twelve years old you got a two-two [rifle], and shooting rifles was just a part of how everybody lived. It’s a completely different thing to the gang-fuelled, ‘automatic weapons in their back pockets’ approach to guns. The gun itself isn’t the problem, the problem is in the operator.

Talking about trying to reduce gun ownership in the United States, as they did in Australia, is just nonsense, man, because two-thirds of households in America have got guns and nobody’s gonna give them back. You’re never going to get rid of them. It doesn’t mean I approve of them. I’d love to live in a world where we didn’t have to have them.

What did you discover about your fellow man during the time you were incarcerated in 1983 for possessing drugs and a firearm?

I learned about racism. I’d met and worked with black musicians who were some of the greatest people on the planet. Odetta and Josh White were my mentors, people I learnt how to be a folk singer from. So I had this great picture of who black people were.

Then I was suddenly in prison with people who couldn’t read a comic book and had nothing left but attitude. They were the bottom end of the Texan prison system and not a good advertisement for people of colour in this country. So I had to wade through that and realise that, no, though some people were pretty terrible, the full range of people was also there. There were angels and demons, and in any group of people bigger than a hundred I was always going to find both. That was a big lesson.

Five years for a quarter of a gram of pipe residue seems like an awful lot of jail time. Do you feel that the various agencies of law enforcement already had their eye on you as a representative of the counterculture and that your position was reflected in the severity of your sentence?

Yeah, sure, they were trying to make an example. I only did a year, but they were trying to make an example. And probably rightly so.

- Our TeamRock+ offer just got bigger. And louder.

- The Top 10 Best David Crosby Songs

- Roger McGuinn: Hendrix, Clapton, Lennon, The Byrds and me

- David Crosby, Ted Nugent in war of words after White House visit

And what did you discover about yourself during the time you spent in jail?

I discovered myself again. When I woke up from the long drug nightmare, I woke up in a prison cell, and while it’s not a great place to wake up, at least you wake up. And I discovered I could live without the drug, which was something I didn’t know. I thought I couldn’t.

I discovered I could manage my life there and stay out of trouble long enough to survive day to day. I learned that I could still write if I went back to it. Because I had done drugs to the extent that they’d wiped out my ability to write completely, and I wasn’t even really awake as a human being. Then I wake up in prison and start reading again, start thinking again and started writing again. That was the big joy, that the writing was going to come back.

Do you write for specific projects as they arise, or is writing an ongoing process?

I just write. I’m always picking up the guitar to see where it’ll take me. When Joni Mitchell and I were going together and I was producing her first record, I said something to her and she said: “Write that down.” And I said: “Write what down?” “What you just said. It was something good, and if you don’t write it down it didn’t happen.” And that stuck in my head. Ever since that day, if I get four words in a row that I like I write them down.

Prior to your liver transplant in 1994, when you were first diagnosed with hepatitis C, the prognosis looked pretty grim. How did you react to your diagnosis?

I didn’t believe it. The first diagnosis was at Johns Hopkins [an academic medical centre in Baltimore] and I didn’t believe them. So I went to UCLA, and they said: “Yeah, it’s absolutely true, you have hepatitis C, your liver is very close to failing. As a matter of fact, we were going to give you a pager and send you home, but we don’t think we could keep you alive at home, so you’re checking into the hospital right now. Seventy-two days in the hospital. It was absolutely terrifying, man.

In 2010, If I Could Only Remember My Name was voted the second‑best album of all time by L’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican’s official newspaper. Did you have any idea that you were quite so Pope‑friendly?

No I didn’t! The next one on the list was Dark Side Of The Moon, so I beat Pink Floyd. As soon as it came out, I got an email from David Gilmour saying: “Damn you, you bastard.” We laughed about it a lot, thought it was funnier than shit. There has to be somebody in The Vatican that’s got really good taste in music, I guess. I’m a huge fan of this Pope. He’s the best thing to happen to the Catholic church in a thousand years. A fine human being who, instead of just talking the talk, walks the walk. I’m not Catholic, I’m not religious at all, but I think he’s terrific.

You’re obviously a passionate man, driven to distraction by injustice and corruption, but you seem to find perfect peace in performance. Do you find the process of making music beneficial to your physical and mental well‑being?

Absolutely, man. Singing for me is a joy. Just as war drags humanity downward, brings out the very worst in humanity, music is a positive, lifting force that brings out the best in us. I love singing. It’s the other twenty-one hours a day that beat the crap out of me – the bad food, no sleep and cheap hotels. But the three hours I’m on stage with the band, that’s heaven to me, man. I’m doing what I was put here to do.

This is taken from the pages of Classic Rock 242. Read more of the issue’s highlights by signing up to TeamRock+ right now.