You wouldn’t use the word ‘prolific’ to describe David Gilmour, at least not when it comes to putting out music. His new album, Luck And Strange, comes nearly nine years after its predecessor, Rattle That Lock, which itself ended a nine-year wait (although to be fair, he had been working on the posthumous Pink Floyd record The Endless River, which came out the year before). Gilmour has never been one to ‘crank ’em out’, of course, and since Floyd’s final tour, in 1994, he’s released just three studio albums.

“I don’t have a huge ambition any more,” Gilmour, now 78, told us during the Rattle That Lock campaign. “In past years there was a lot of thinking about the career and wanting to achieve success. It’s sort of turned into something more calm and less ambitious in my later years. I’ll get round to doing something again before too long, I hope, but I have no idea. I haven’t planned anything.”

Fair enough. But we’d like to disagree with the ‘less ambitious’ part. When Gilmour does release a record, it is the product of great ambition and invention, and of a good deal of work that’s gone on even before he and his collaborators get into the studio. It perhaps hasn’t produced a substantial amount of music over the years, but it’s always resulted in work that is vital and compelling, something new and interesting each time.

Luck And Strange is the latest case in point. It’s Gilmour’s fifth studio album overall. His first, self-ftitled, came out in May 1978 while Pink Floyd were on a break prior to making The Wall, and had Gilmour producing and leading a core trio that included bassist Rick Wills and drummer Willie Wilson from his pre-Floyd band Jokers Wild. About Face, in 1984, helmed by Gilmour with The Wall cohort Bob Ezrin, had a rhythm section of Toto drummer Jeff Porcaro and journeyman bassist Pino Palladino, with Steve Winwood and Deep Purple organist Jon Lord among its guests. The latter record also set Gilmour out on his first solo tour.

After a Pink Floyd resumption (without Roger Waters) during the late 80s and 90s, Gilmour took his own counsel again on 2006’s On An Island, with Floyd keyboard player Richard Wright, Roxy Music’s Phil Manzanera, David Crosby, Graham Nash, latter-day Floyd bassist Guy Pratt, Jools Holland and others among the illustrious company.

After Gilmour’s wife, Polly Samson, contributed to Floyd’s The Division Bell, she became his chief lyricist on six of the 10 tracks on On An Island, and provided piano on one and backing vocals on another.

Gilmour teamed up with The Orb for the 2010 electronica set Metallic Spheres before making The Endless River and Rattle That Lock, again co-producing with Manzanera on the latter and with many of the same collaborators, and Samson writing five more sets of lyrics.

Gilmour’s Floyd-like live extravaganzas were released on album and video packages such as Live At Gdansk and Live At Pompeii. The sale of some of his guitars at Christies in June 2019 made £16.5 million.

Music was still being made at home when the pandemic hit in 2020 and turned the world upside down. But it was a fruitful time for Gilmour, who, in helping Samson promote her novel A Theater For Dreamers, began doing virtual performances. Those helped bring their daughter Romany and sons Gabriel and Charlie into the musical mix, too. When lockdowns lifted and Gilmour turned his attention to a new album, he was ready to rattle any locks that had become part of his creative world.

To that end, he and Samson worked for the first time with co-producer Charlie Andrew, an award winner whose credits include working with indie rockers alt-J (including their Mercury Prize-winning An Awesome Wave), Matt Corby, Marika Hackman, James, Bloc Party and more. He’s of a different generation and a different sensibility; Gilmour has admitted that Andrew even questioned the need for guitar solos.

“I did start by saying: ‘Do we need another guitar solo here?’” Andrew acknowledges. “I just want what’s best for the song.” That said, Andrew agrees that it’s nice to have a big solo, “because that’s what he does. I definitely came at it with an angle of: ‘We don’t need to have things if they’re not essential to the song.’ Obviously, saying that, David is a truly exceptional guitarist, and it was lovely to have moments in the studio when he was trying to work out a part and all I had to do was sit there with my coffee and listen. I definitely have a greater love for guitar solos now. Well, David’s guitar solos.”

What’s clear is that Andrew made Gilmour think fresh, and more new faces – drummers Steve Gadd, Adam Betts and Steve DiStanislao and keyboard players Roger Eno and Rob Gentry, as well as old-hand bassist Pratt – brought energy and an ensemble sensibility that made Gilmour even more excited about the proceedings at Mark Knopfler’s British Grove studios.

The freshness fills Luck And Strange’s nine tracks, from the brief instrumentals Black Cat and Vita Brevis to a cover of the Montgolfier Brothers’ Between Two Points, sung by daughter Romany and featuring a couple of Gilmour’s trademark majestic solos. The title track dates back to 2007 and the jams Gilmour held with the band that had toured to support On An Island, including Wright. A lengthy “barn jam” version included on the album reveals how the track evolved from much broader ideas at the time.

Most of the songs are at a measured, mid-tempo pace, with Yes, I Have Ghosts in acoustic-folk territory. The compact Dark And Velvet Nights is the album’s most upbeat track. And despite any of producer Andrew’s reservations, Gilmour happily solos throughout, taking flight on tracks including The Piper’s Call, A Single Spark and Scattered.

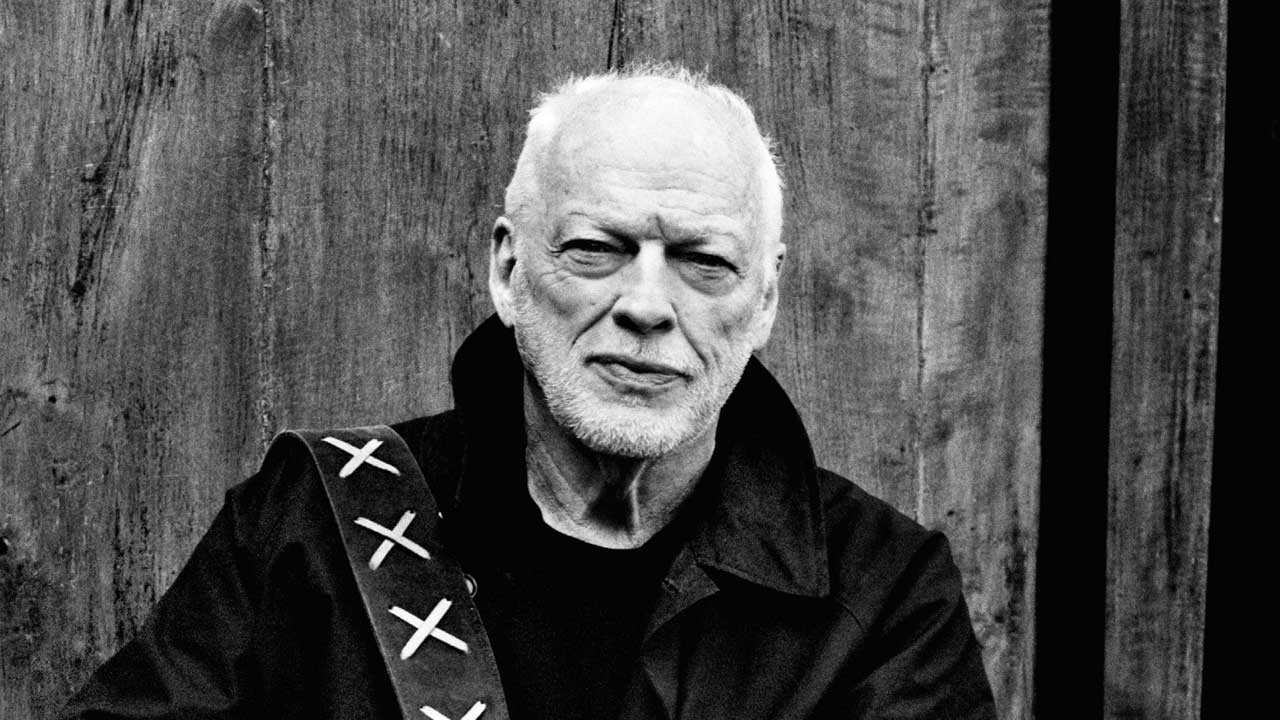

Luck And Strange has given Gilmour a great deal to talk about, of course, including a selection of shows at London’s Royal Albert Hall and others in New York and California. When we catch up with Gilmour it’s on board the Astoria, his houseboat on The Thames. He bought it in 1986, outfitted it with a recording studio and made the final three Floyd albums and some of Rattle That Lock there. Today his T-shirt is black, his tightly trimmed beard is white, and his satisfaction with Luck And Strange bubbles over throughout our chat as he considers this latest chapter in his long and illustrious career.

It’s been a while since you made Rattle That Lock. Do you feel the passage of time, and does it affect how you approached Luck And Strange?

I don’t know if it’s the passage of time, but there have been lots of things that have gone on in our world in the last few years that have definitely impacted my thinking and approach to where this album grew out of.

Some of those things seem obvious…

Well, I mean, first of all I’d have to say covid and the lockdown, being locked at home with my family, with the thought, and the general, broader thought of experts, that old folks like me were liable to get wiped out any minute by covid, and some vast percentage of the population was going to die [grins]. Those were real thoughts, real sort of semi-accepted ideas in 2020. Which proved to not be quite as dangerous as we thought at first.

But I was locked down with Polly and with some of my kids, and the topic of discussion was often toward the aging process and the dangers of this covid thing. So those topics are things that have surfaced, through Polly, in a lot of the lyrics on this album. And of course the other thing is family, working with family, indulging in a nice bit of nepotism.

Which we got a first taste of in the virtual performances you did during lockdown.

Polly’s book A Theater for Dreamers was supposed to come out the week we had lockdown in England, and that was tricky for her, because the whole sale and promotion of her book was put in jeopardy. And she wants people to read her book, of course, as you do. It’s a brilliant book.

Anyway, Charlie, our son, when we had to cancel some shows we were going to do around England – semi-literary, partly music – Charlie said: “Why don’t you stream them from home?” This is not an idea we were used to, but we went there, and it started pretty much only on Polly’s book as a focus. But then it became broader. I was singing songs every week – usually Leonard Cohen covers, becauses he’s a character who appears in her book.

Then we got our daughter Romany to sing along and play with me, and that showed me that we have got that lovely sort of family tonality that happens – the Beach Boys, Everly Brothers and other people. These are things that we loved in the past. So all these things came together to create a different mood and a different feeling for the making of this album.

Kind of a clean slate, or a new palette?

Liberated. Liberated from the past. These things, the covid and the aging and the family, all these things left me feeling that I don’t need to stick with any rulebook or anything that’s gone before. I can be freer, liberated to do anything I feel like. I’m not tied to it sounding like this or that. That sort of became emphasised for me.

How did that manifest itself in the album itself? You worked with a lot of new people, producer Charlie Andrew included. What did that allow you to do differently from before?

That’s all there in the music, and they’re there in what Charlie brought to it and my acceptance of what he was showing me and the direction he was proffering. It all just helped move things in a different direction that felt like a liberation to me.

This is a guy you’ve said was asking if there had to be guitar solos. You’re David Gilmour. How do you answer something like that?

That’s a very interesting thing about the whole situation. He’s forty-three or forty-four or something – he’s not a tiny kid or anything – but in his passage through music Pink Floyd wasn’t one of those influences. Amazingly enough there still are people like that [chuckles]. But he liked the music that I was working on, and I liked him. Polly liked him very much. She found him, really, and I thought it was an interesting and exciting way for us to move forward.

Was there an ensemble sensibility around Luck And Strange that was different from what you’d had on your other albums?

This feels like a team in a way that the other solo albums didn’t. On those albums, I felt like there was a bit more of a burden on my shoulders in the writing and in the execution of the whole thing. I started off in a pop group, and I found myself eventually in the position of leading that group – not a position I was hoping for or looking forward to.

And being a solo artist, also not what I asked for. I always preferred being part of something, and this album feels much closer to that than anything I’ve had over all those years. It all felt much more like a family, much more like a group of people working toward a common end, than I’ve felt in quite a while. And it’s exciting. It’s fun.

You’ve said you feel this is the best thing you’ve done since The Dark Side Of The Moon. That’s a pretty weighty comparison. What makes it feel that way?

The album feels like a solid body of cohesive work that is a reflection of some of those things that I’ve tried to describe to you. It’s the cohesiveness of the whole thing – the writing, the work, the thrill it still gives me to listen to it all the way through as an album. We’re not talking concept album here, but there’s a consistency of thought and of feeling that runs through it that excites me in a way that makes me make those sort of comparisons.

You’ve produced your previous solo albums, or co-produced with familiar company such as Bob Ezrin and Phil Manzanera. What was it like turning it over to someone new and younger?

Charlie’s lack of being overawed by my reputation was a big plus for me. Obviously in the position that I find myself there is likely to be too much… sycophancy, if you like; too many people saying: “What you’re doing is wonderful.” It’s just a natural way that things tend to work out. But Charlie didn’t have any of those particular, specific problems, and that was very refreshing. So when he’s firm in his convictions on the way we should try to do something a certain way, you give it a go and you give it some time, and if you don’t think it’s right you try a different approach. You can go to these things and try them one way, try them another way.

What directions did he push you in that felt new, or maybe even uncomfortable for you?

There’s things to do with the sound, the way he wanted to record, and how long I’d be willing to keep going at something until we got whatever it was he was searching for out of me or the other musicians. He worked us very hard, all of us. It was very good for me to be there while he worked some of the other musicians on the tracks before I got to the singing parts. I knew what was coming for me, and it was the same thing he’d done with Steve Gadd and people. So the sound was what he was going for.

The demo for the song A Single Spark is one of the extras that’s on the bonus CDs, and you can hear the difference that he brought to that. With that track in particular, it took me a little while to get used to the radically different approach he took from my version of the song, but now I couldn’t love it more. So those things that he brought to us went right through the process, from the beginning of the album to the end.

Did he develop a little awe for you by the time it was finished?

I think he did learn to love guitar solos more by the end of the album than he did at the beginning [laughs].

Let’s talk about solos, then, and how you approach them. Did having someone else doing some of the heavy lifting in the production allow you to approach your playing, especially the solos, more unconsciously?

In guitar soloing, you want to be detached from too much brain work. You want it to flow freely, like a spirit, and find exactly the right sort of mood for playing things. For some of the solos on it, that approach worked really well. There are other songs where you’ve got a plan for the solo and you’re gonna work in a specific way toward achieving something that you’ve already got in your head.

Sometimes when you’re working on a guitar part or a guitar solo, you can already have the idea for it in your head and you really have to work at it. And there’s another approach where you empty the head and you don’t think, you just let the track take you wherever your brain, your fingers and the muse take you.

When you listen to the album now, what are the surprises?

I don’t know that I can answer that. I mean, every time I listen to it I’m surprised anew at how much I love it and how satisfying it feels to me.

When Rattle That Lock came out, you mentioned that you still had a lot of ideas left that you planned to explore further. Did any of those ideas show up on Luck And Strange, or is it mostly newer material?

I’m a bit of a magpie. I have lots of pieces of music, and I pick and choose between things. Sometimes out of nowhere I’m thinking of one piece of music, and then I think of another one that’s completely disconnected that’s at the same tempo and same sort of feel, and I think: “Well, could they work together?”

There’s another track, Sings, for example. I wrote the basic music for it not long ago – five years ago maybe – but I didn’t have a chorus. I eventually remembered a chorus I’d done many, many years ago, in 1997 in fact. The chorus comes from then, from a demo I did on a Minidisc recorder, with my son, who was then two, telling me to sing – “Sing, daddy, sing!” And we actually put that demo on that track. He’s now nearly thirty. So I’m certainly not against digging back through the hundreds of pieces of music that I’ve got stashed away somewhere.

On Luck And Strange there’s a “barn jam” version of the title track, which has Rick Wright playing on it. How did the song transform from that to what we hear on the album?

At the end of the On An Island tour [in 2006], I thought the band was really sort of hot and playing great together. So I took the core of the band – four guys: drums, bass, guitar and keyboards – and we set up in a barn at my house and recorded for two weeks, just jams. This was the first one we did on the first morning. I just started playing that little guitar piece and they all joined in.

And then, quite a while ago – I suspect it was some time before the Rattle That Lock album – I wrote and recorded bridges and choruses to that backing track. And again, I puzzled myself: I don’t know why in 2015 or 2014 I didn’t listen to that track and go: “Yeah, let’s go!” But this time it demanded to be heard and worked on, so we did.

Does it mean a lot to you to still have Rick in your musical world in some way?

Yeah, it’s wonderful to have a track that he’s actually a part of. Rick’s unusual playing style pours out of it, and makes me sad that he’s not around to take more part in what I’m doing.

Returning to Luck And Strange’s lyrical theme, especially on the title track, what is that idea about?

It’s the luck of the very strange moment that me and baby boomers in general – all of us who were born in the postwar period – have lived through, to have had such a fortunate moment, with so many positive ideas that we thought were moving us forward. This is a conversation that Polly and I have had and she has written about in those lyrics.

It’s really a question: what’s normal? Was that baby boomer era – what some people call a golden age – was it normal? Or is it these darker times – the wars and the politics, and the lunatic Trump that you’ve got, and the lunatic Putin over in Russia – is that the norm? That’s the conversation, between which moment is the norm and what have we got to look forward to in the future.

Writing song lyrics with one’s wife seems like something that could be a bit… dangerous?

[Chuckles] Polly and I really are a team. We’ve been writing songs together for over thirty years now. We are very much in sync with each other in what we want to do, and this album is the result of that reaching a firm… er… better point in that process.

Polly’s just a great person to work with, and having been a professional writer most of her adult life she’s extremely good with words. Her influence goes as far as which pieces of music go on the album, to some extent. If there’s something that she really likes and wants to write to, then obviously it stands a better chance of being on an album.

She used to try very hard to imagine herself as me and to be writing things for me, but I think she’s liberated herself a bit from that view and now realises she can write for herself and it will still – because we share so many views, political or philosophical – work perfectly well for me. I’m singing them, so they come out sounding like me. I’ve got a lot of experience singing other people’s words, but with Polly it’s working really well as a partnership, and I’m thoroughly enjoying it.

Will we have to wait another nine years for your next album?

My intention is to gather some of these people together and get back and start working on something else in the new year. What you want is a few things to get started with and hope it all starts flowing, and that’s what I’m hoping will happen.

Pink Floyd — dare we ask?

I put the whole Pink Floyd thing to bed many, many years ago. I mean, it’s impossible to go back there without Rick, and I wouldn’t want to. It’s all done. I’m very happy and satisfied with the little team I’ve got around me these days. We had a lot of offers to go and tour and so on and so forth, but I’m in this selfishly lucky position of having more than enough money and having had more than enough fame.

I just don’t need that stuff these days. I wouldn’t want anyone to get the impression that I am not a hundred per cent happy and satisfied with the work I’ve done with Pink Floyd over the years, which were productive and satisfying and joyful, mostly. It’s fantastic. But my focus is different right now.