Billy Duffy first clapped eyes on Ian Astbury in the grounds of Keele University. “He was going through the bushes, wearing buckskin chaps that he’d made himself, a blanket loincloth wrapped up like a nappy, and these moccasins with bells on,” says Duffy. “He looked like Daniel Day Lewis in The Last Of The Mohicans, except he jangled when he walked. I thought: ‘That’s a bit interesting.’”

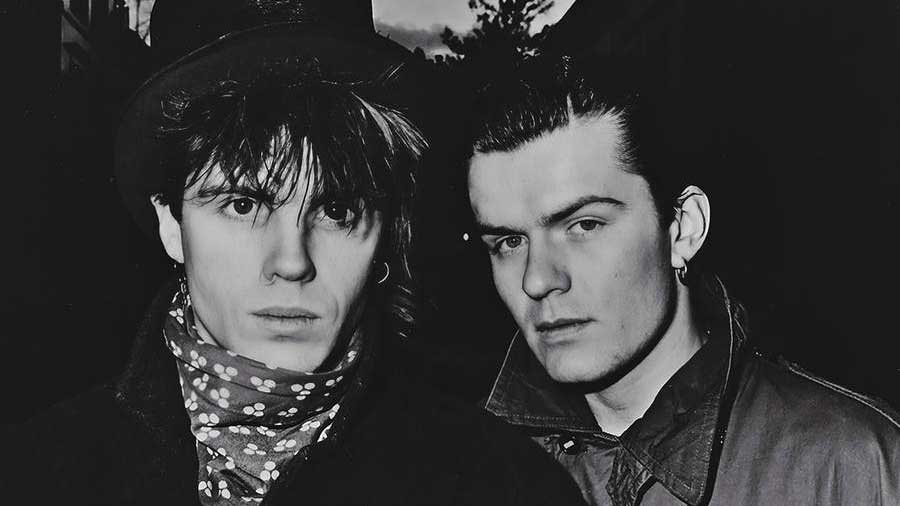

It was February 23, 1982. Duffy was the black quiffed, white Gretsch-wielding guitarist with post-punk gunslingers Theatre Of Hate, who had just edged into the UK Top 40 with the pulsing, Spaghetti Western-edged single Do You Believe In The Westworld. Astbury was the mohawked singer in rising Bradford ‘positive punks’ Southern Death Cult, who were opening for Duffy’s band on their current run of dates, including Keele.

Duffy had heard the name Southern Death Cult, but didn’t know anything about their music. The two men got talking pre-show. “We bonded over Embassy cigarettes,” says Duffy. “In that I had them and he wanted one.”

That evening, the guitarist watched the support band’s set. “They’d start playing this song called The Crow, building up this atmosphere, and then Ian would boogie across the stage doing his Indian dance,” he says. “And then this voice appears.”

Duffy didn’t know it at the time, but that voice – Jim Morrison by way of UK punk – would soon be intertwined with his guitar. Less than a year after that first meeting, both he and Astbury were out of their respective groups and plotting a musical future together. That initial connection sparked a blaze of creativity that has burnt for most of the last 40 years, briefly under the name Death Cult and, more prominently, as simply The Cult.

Billy Duffy and Ian Astbury were born a year and two days apart, the former in Manchester in May 1961, the latter in Birkenhead in May 1962. Both came from working-class backgrounds and both were children of punk. Duffy’s first band were local Wythenshawe heroes The Nosebleeds, briefly fronted by future Smiths singer Morrissey. He eventually moved to London and got a job working at fashion boutique Johnsons. Then the call came in the autumn of 1981 to join Theatre Of Hate.

Astbury was equally all-in. He fell in with the anarcho punk scene, following Crass around on tour and living in various dilapidated squats. By 1981, he was living in Bradford and put together Southern Death Cult with like-minded musicians. Duffy had stayed in vague contact with Southern Death Cult after their brief run opening for Theatre Of Hate.

“I remember socialising with them and sensing that there was a bit of separation between Ian and the rest of the band,” he says. “Looking back, it seemed like he wasn’t digging the interpersonal relationships.”

Duffy was having his own issues. He was been unhappy with what he calls “the toxic atmosphere” in Theatre Of Hate. Frontman and driving force Kirk Brandon was having none of it. Following an awkward conversation in the van on the way back from a gig, Duffy was asked to leave the band. “I’d given up a cushy job and having somewhere to live, spent all my money on a Gretsch and ended up penniless and homeless,” he says.

He wasn‘t quite homeless. He shared a flat with Theatre Of Hate’s merch guy in Brixton, South London. It was a rough area but rents were cheap, and it was a magnet for musicians and artists. People would regularly crash on Duffy’s sofa. “Imagine a gothic Laurel Canyon,” he says.

His abrupt exit from Theatre Of Hate hadn’t dented his desire to be in a band. There was just one problem. “I was sitting there in my flat in Brixton, scratching my head, thinking, ‘I don’t even know if I can write,’” he says. “I was always the guy who got hired because I looked good. I was always in bands with other people who wrote the songs.”

That situation changed in early spring 1983 when Ian Astbury turned up on his doorstep. “He was wearing a top hat and had a carrier bag full of clothes,” Duffy recalls. “He said: ‘I’m leaving Southern Death Cult. Do you want to form a band?’ And I thought about it for half a second and went, ‘Yeah, sure, I’m in.’”

Ian Astbury saw the writing on the wall for Southern Death Cult well before he rocked up at Billy Duffy’s flat in Brixton. His band appeared on the cover of the NME in October 1982, before they’d even released a single. The CBS label, home of The Clash and Adam And The Ants, had offered them a deal worth $100,000. It was too much for the singer. “The pressure was immense,” he said in 2019. “It was going to explode.” And so here he was, crashing on Duffy’s sofa in the spring of 1982 while the two plotted out a mutually beneficial future.

“Me and Ian weren’t concerned with what other people thought we should play – all this pre-post-positive-punk-newage-psychedelic-gypsy stuff,” says Duffy. “We just wanted to be a guitar-orientated rock band.”

The first thing the pair wrote together was Brothers Grimm, based on a riff Duffy had come up with for a band he’d been talking about doing with former UK Decay singer Abbo that never happened.

“One of us would have an idea and we’d just do it,” says Duffy. “There was nobody telling us: ‘Oh, you need an eight-bar thing there or pre-chorus there.’ It was just three chords and an attitude.”

They brought in Sierra Leone-born drummer Ray Taylor-Smith, aka Ray Mondo, from proto-goth band Ritual. He bought along his former Ritual bandmate, Jamie Stewart, who swapped from guitar to bass, gifting Duffy his old effects pedals in the process. “He said: ‘I won’t be needing these any more,’” says Duffy. “And then we were up and running.”

But they still needed a name. They didn’t want to call it Southern Death Cult, but they couldn’t think of anything else. “I was, like: ‘Fuck it, let’s call it The Brown Shoes,’” says Duffy. “That might have actually been a genius idea considering The Smiths were about to happen. In the end we just decided on Death Cult.”

Martin Mills, founder of influential independent label Beggars Banquet, agreed to release their self-titled debut EP via Beggars offshoot Situation Two. The latter had released the ill-fated Southern Death Cult’s sole single late the previous year.

“I’m sure the last thing he wanted to hear was that Ian had left Southern Death Cult, but I must have convinced him that we weren’t lunatics,” says Duffy. “He took us seriously.”

The four song Death Cult EP, recorded in London’s Wessex Studios with producer Jeremy Green, was released in July 1983, just over four months after Astbury and Duffy started working together. Its four songs – Brothers Grimm, Ghost Dance, Horse Nation and Christians – shared DNA with Astbury’s previous band, not least via the singer’s lupine howl. But their sound was defined, too, by Duffy’s chiming guitar and Ray Mondo’s African-inspired rhythms.

The EP’s cover featured a shot by Vietnam war photographer Tim Page taken from inside a US helicopter gunship. It tied in with the band’s early visual aesthetic: all army surplus style combat jackets, para boots and, in Duffy’s case, a green beret.

“I was obsessed with Vietnam because it was a rock’n’roll war,” says Duffy. “The Doors and Hendrix were on the Apocalypse Now soundtrack, which had come out a couple of years earlier. It was escapism from dreary old London.”

If the guitarist fancied himself as Charlie Sheen’s Captain Willard, then his bandmate was Crazy Horse. Astbury’s interest in Native American culture had been sparked when he moved to Canada with his family in his teens. Southern Death Cult took their name from anthropological term for a group of tribes located near the Mississippi river, while the Death Cult songs Ghost Dance and Horse Nation both traded in indigenous imagery – the latter lifted its lyrics almost verbatim from Dee Brown’s 1970 non-fiction book Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee.

“I had no personal connection to it, but it appealed to me,” says Duffy. “It was an underdog point of view. It’s still quite timely to this day: take care of the Earth. If you don‘t have water and oxygen, there ain’t nothing else matters.”

Death Cult played their first gig on July 25, 1983, at Rat’s Bar, a punk rock biker dive in Oslo. “We thought: ‘When Led Zeppelin started, they went to Scandinavia to play their first gigs under the name the New Yardbirds. Why don’t we do a few of those then come back?” Duffy says.

In October 1983, the band released a new seven-inch, God’s Zoo, and recorded a session for BBC DJ David ‘Kid’ Jensen. The latter was produced by Dale Griffin, formerly drummer with Duffy’s childhood idols Mott The Hoople. “He was like a grumpy old man who spend most of his time in the pub,” says Duffy. “It broke my heart. I just wanted to ask how he got that drum sound on Mott The Hoople Live.”

By that point, there had been a drummer swap. Unwilling to play straightforward rock beats, Ray Mondo had left to join Sex Gang Children, whose drummer Nigel Preston had come the other way to Death Cult.

“Nigel was an excellent drummer, very professional, but mad as a box of frogs,” Duffy says of Preston, who died of an overdose in 1992 at the age of 28. “He always wore a suit in every single one of our photos.”

But the biggest change wasn’t in personnel. Duffy and Astbury decided to truncate their name. Death Cult became The Cult. It was, says Duffy, a purely commercial decision.

“There were a lot of bands coming up who were being lumped together in some kind of gothic post-punk scene – Ghost Dance, Skeletal Family, Specimen,” he says. “We felt that having Death in our name would get us lumped in with that, and we didn’t want to be. I didn’t think it had longevity.”

The rechristened band made their debut appearance on Channel 4 music show The Tube on January 13, 1984. Vintage YouTube footage shows Astbury looking striking in a red military jacket and with face paint, while Duffy is clad neck-to-toe in black, brandishing his beloved white Gretsch. Their short, five-song set kicked off with a brand new song, Spiritwalker, another example of the singer’s fascination with Native American culture.

Spiritwalker was released that May as a single, the first to bear The Cult’s name. Their debut album, Dreamtime, followed three months later (Duffy refutes Wikipedia’s claim they had an album titled Flowers In The Desert while still called Death Cult). The guitarist has mixed feelings about Dreamtime today.

“We weren’t quite making the music we felt we wanted to,” he says. “Killing Joke, Bauhaus, The Danse Society, they’d all been on Top Of The Pops, but we hadn’t. We were playing the same size gigs as these bands, so there was a fuckton of pressure to come up with a hit. And that’s when She Sells Sanctuary just dropped into our world.”

She Sells Sanctuary was a tipping point in The Cult’s career. A patchouli-shrouded psychedelic-goth dancefloor filler, the 1985 single marked the point where the band stepped out of the margins and into the spotlight.

“To me, that’s the end of the first chapter,” says Duffy. “It goes Death Cult to She Sells Sanctuary and then She Sells Sanctuary to everything after.”

Duffy and Astbury recently revisited the Death Cult days, playing a sold-out UK tour focusing on material from their earlier years (“It won’t happen again, it was a one-off,” he promises). Today, he looks back with fondness at that overlooked period of what Duffy calls “the cartoon pirate ride” that is The Cult’s career.

“A lot happened in such a short time back then,” he says. “We were really just punk fans who learned to play and found our own musical voice. We rolled our sleeves up and started scheming forty years ago, and we haven’t stopped scheming ever since.”