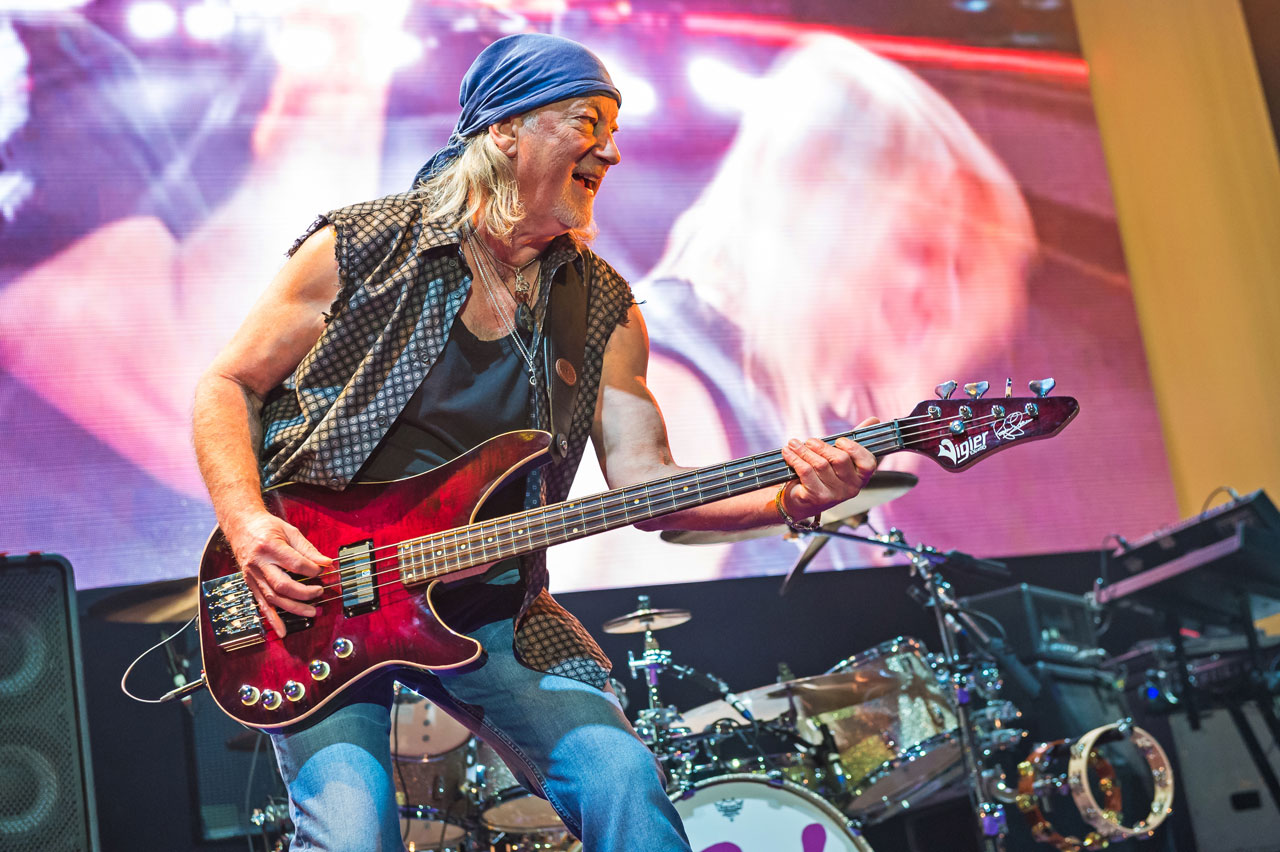

The making of InFinite, Deep Purple’s looming twentieth studio album, is charted in a new Sky Arts TV documentary, From Here To Infinity. In one sense, at least, it marks clearly the span of time that has elapsed since the band formed in far-off 1968. Ian Gillan and Roger Glover, both now 71, the 68-year-old Ian Paice and Don Airey, and Steve Morse, at 62 the baby of the band, each wear the years with their greying hair and reading glasses. Or as Gillan puts it: “We’re all knocking on a bit. I walk down the road and hear a clang on the pavement – something else has dropped off.”

As well, there is the presence of ghosts and elephants in the Nashville rehearsal room where InFinite took shape. Notably and respectively, those of two of Purple’s founding members: Jon Lord, gentleman keyboard player, and Man In Black guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, the perceived villain of the piece. Yet in another regard the film seems frozen in time, ageless. In one scene after another, the band’s five current members hunker down in the room, arranged in a loose circle, and work songs up to tape. All the while, veteran producer Bob Ezrin prowls among them, coaxing and cajoling. This was how Purple made records in the 70s and during their pomp, trying on the fly to capture lightning in a bottle.

It’s the same team that made the band’s previous album, 2013’s Now What?!. That was their first in eight years and a partial return to form. Prior to then, and after Steve Morse had given them a shot in the arm when he replaced the toxic Blackmore for 1996’s Purpendicular, their recorded returns had been diminishing. Better, stronger and more cohesive than its immediate predecessor, InFinite continues the upward curve. Tracks such as High Boots and One Night In Vegas are light-footed and vibrant, while a brace of swaggering epics, The Surprising and Birds Of Prey, could not be the work of any other band.

Gillan’s voice has long been unmistakable. Likewise Paice’s swinging, shuffling drums. And Airey, like Lord before him, summons a squelching Hammond. Put together, and mixed in with the jazz, rock’n’roll, pop, blues and folk influences that were initially stirred into Purple’s pot, these were the trace elements of hard rock at the dawn of the 70s and its bedrock through the next two decades and beyond. Purple’s very being now seems like an act of defiance to the shifting sands of taste, trend and technology.

“I don’t know about defiant, but it’s just what we do,” offers Paice. “Admittedly we had a few years where we didn’t see the point of going in and making a record. But when we did again with Bob [Ezrin] back in 2012, I think for all of us it was the first time in a long while that we actually enjoyed being in the studio.”

“Deep Purple is primarily an instrumental band,” says Gillan. “When we met with Bob, he said he wanted to get us back to where we were, which was to extemporise on musical ideas without any restrictions of time. If an idea justifies itself, then it’s worth stretching. The first three albums I made with Purple only had seven tracks on each. And some of the textures and dynamics on this one are just amazing to me.”

Indeed, as he’s caught on film in the documentary, watching intently as the others lock into one heaving jam after another, Gillan’s appreciation of the band is self-evident.

“For sure,” he agrees. “I remember back in 1969 when Roger and I did our first show with Purple at the Speakeasy. There were only twelve people there; well, twenty if you counted Keith Moon. But I looked at Roger and said: ‘Oh man, this is it.’ It was the kind of band we had both been dreaming of. We had all of us been through the pop thing, so we just thought we would please ourselves and hope that other people liked it. Actually, we didn’t even give much thought to that.”

In the most intimate scene in the film, Gillan, Glover and Paice reflect on the moment, in July 2012, when they learned that 71-year-old Lord had lost his long battle with cancer. At the time, they were also in Nashville and working on Now What?!. Breaking off, the three of them gather round and begin to reminisce, sharing memories of Lord, who had retired from playing with Purple 10 years earlier and was still beloved by them all.

InFinite and the accompanying Long Goodbye tour are being rolled out by Purple’s people with all the solemnity – and branding – of final acts. If they are indeed about to follow Black Sabbath into history, Purple’s passing would truly mark the end of not just one of rock’s most colourful sagas, but also of a once golden age as a whole. Except this being Purple, whose existence has often appeared to be predicated on internal conflict, none of the band seems able to agree on when or how their end will ultimately come about.

“If you want to be literal about it, 1969 was the beginning of the end,” reasons Glover. “The actual answer is we don’t know. The idea of when and where we’re going to stop has been around for the last couple of years, but we haven’t been able to come to any definite conclusion.”

Steve Morse’s response to the same question is rather different. “The way I’ve been told it, this tour is probably our last big one,” he says. “I’m positive the band members will continue to make music in various ways, but the idea is to let everybody know that this is goodbye in the sense that it could be the last time most people will be able to see us live.”

“It’s all a bit haphazard,” concludes Gillan. “One just looks forward to the next show. And our retirement will be as chaotic as the rest of our lives.”

Ian Paice has been there from almost the very start. Born in Nottingham in 1948, he got his first set of drums at 15, inspired to play by such big-band era greats as Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich. His first public performances were with his dad’s dance band, and by the mid-60s he was in a beat group called The Maze. When in 1968 that band’s singer, Rod Evans, was poached to join the fledgling Deep Purple, the 19-year-old Paice went right along with him and hooked up with Blackmore, Lord and bassist Nick Simper.

“For the first two or three years of Purple I was just a kid in a candy store,” Paice says. “I didn’t think about anything other than playing, drinking, chasing ladies and having a party. The reality and seriousness of what we were doing was totally unimportant to me.

“Sometimes I see pictures from very early on and I know it’s me, but I have no recollection of the moment. I saw something not long ago. There was a film we did in France in 1968, or ’69. It was like an early video for Kentucky Woman and we’re all romping around a garden. I remember the clothes I was wearing, but I can’t recall that day at all. A lot of these things are ancillary. You do them because you’re asked, but not with any great joy, whereas I haven’t ever let go of the music.”

Today, Paice is at his home in the English countryside. Having made a full recovery from the minor stroke he suffered last summer, he’s off in a week’s time to play a date with a Purple tribute band in Germany. This, he notes, is a semi-regular occurrence. He did another in, of all places, Minehead a fortnight back.

“You have to play, it’s no good resting on your laurels,” he says. “It drives me nuts when I see young bands today come off a four-week tour and they’re absolutely shattered. They’ve travelled fairly comfortably and the hotels are decent, and they always get paid. I’m trying not to say ‘in my day,’ but it was that much tougher. You didn’t think about it, though, because you were having so much fun.”

Unprompted, Don Airey hails Paice as “the best drummer in the world”. For sure, he is Purple’s engine. On InFinite, his playing is at the same time liquid smooth and powerful, urging, prompting and driving the band as a whole. It was Paice’s subtle finesse around the kit that made Purple’s best-loved song, Smoke On The Water, skip and bounce along. Tellingly, whenever the song is being played by anyone else it sounds like a dirge.

“Although I’m playing rock and roll, I don’t play like other rock and roll drummers,” he reasons. “Since my early influences were big-band jazz, there tends to be a swing to what I do which most rock drummers have no concept of. The amazing thing with that song, and Ritchie’s riff in particular, is that somebody hadn’t done it before, because it’s so gloriously simple and wonderfully satisfying. And the chorus is brilliant. It’s the whole package.”

Roger Glover shared a flat with Paice for two years in the early 70s but says he didn’t get to know him any better in all that time. “I love Ian dearly, and over the years he’s improved as a socialite,” Glover says. “But he is an inscrutable man.”

Ian Gillan offers another perspective. According to him, Paice is “side-splittingly funny” and the more so after a couple of Jack Daniel’s. Yet Gillan adds that in the long cold winter that set in between Purple’s Perfect Strangers reunion album of 1984 and 1993’s aptly titled The Battle Rages On, and after which Blackmore stormed out of the band for good, Paice went inward, becoming a near-silent presence among them.

- Deep Purple reveal InFinite tracklist

- The Story Behind The Song: Mary Long by Deep Purple

- Deep Purple’s Roger Glover: No one wants to stop

- Deep Purple - InFinite album review

“Towards the end of Ritchie’s tenure, every night there were four people up there on stage who were trying and one who wasn’t,” Paice reflects. “It was very obvious. And the audiences got smaller and the gigs crappier. All this depressive stuff came from one guy who didn’t want to play. And at the moment Ritchie announced he was going, and after a couple of days of: ‘What the hell do we do now?’ it was like a big weight being lifted off our shoulders.”

Jon Lord’s passing hit Paice especially hard. After Purple first flamed out in 1976, the two men had gone on together to form the ill-fated Paice Ashton Lord and then partnered up for several more years in former Purple singer David Coverdale’s Whitesnake. By an odd quirk they were also brothers-in-law, having married twins. Paice recalls Lord now with deep affection, and in particular the older man’s erudite wit and boundless capacity for alcohol.

“God, Jon could drink and drink and never seem drunk,” he says, laughing. “He was a wonderful raconteur, telling stories that you had heard twenty-five times before and would still make you roar with laughter. After nearly fifty years, you end up with a lot of funny stories.”

For his part, Paice says “it’s hard to accept that this thing you helped to create and grew up with will be no more. When we can no longer cut the mustard on stage, then we’ll think about hanging the boots up.

“Go and listen to Made In Japan,” he says of the band’s legendary live album of 1972, “and glory in the fact that there were a bunch of kids who could back then capture all that craziness and still have a measure of control. Now listen to what we’re doing all these years later, and inside we’re still a bunch of kids. You don’t have to lose your love for making music.”

To Ian Paice, Roger Glover, his foil in Purple’s rhythm section, is “more the hippie now than he ever was. And he was a pretty big hippie from the outset.” Don Airey, on the other hand, describes Glover as the band’s “Mister Dependable”. Glover acted as producer and diplomat during the latter-day Purple’s warring years. He was the one who would try, often as not in vain, to keep everyone else happy, picking up the debris after each bust-up.

At 11am on this late-winter’s morning Glover is at home in Switzerland and having just got out of bed. He has religiously kept a journal for many years, but says these days the entries he records when off the road have a singularity about them.

“It’s pretty boring stuff,” he explains amiably. “‘Got up, had a meal, went to bed.’ Sometimes for a bit of variety I won’t eat. I’m a songwriter, so I go off into a dream world quite frequently.”

Glover was born in Brecon, Wales two months after the end of the Second World War. He moved to London with his family at 10 and by his late teens was playing in a jobbing pop group, Episode Six, who in 1965 brought in Ian Gillan as their singer. Four years later the two of them jumped ship to take over from Evans and Simper in Deep Purple and establish the formidable Mark II line-up of the band. Within another four years Purple had made three epochal albums – In Rock, Fireball and Machine Head, not to mention Made in Japan – and otherwise toured relentlessly. By 1973 they were the biggest-grossing act in America.

“In seventy-two alone we did six separate tours of America, one of Japan and made Machine Head,” Glover says of the frantic pace Purple kept up. “Recently I was looking down a list of every gig we’ve ever played, and it is exhausting – page after page. And every single line represents twenty-four hours that I spent travelling and then getting on a stage. A lot of it is a blur to me now. I can remember coming in to land in Los Angeles one time and looking down at row upon row of houses and wondering how many of them had a copy of our record inside. That was my way of trying to take in the enormity of it, but I never quite could.

“Ian Gillan and I especially are like brothers. Sometimes we fight and fall apart, yet we’ve always loved and respected each other. He’s a very creative man and also an unusual, idiosyncratic guy. We’re not alike at all, but we complement each other. He’s the unpredictable wild man and I’m the poet. I’m the soft one and he’s hard. When we get together it’s to write, and that’s the way it is.”

The ups and downs of Glover and Gillan’s long relationship have been mirrored 10-fold by those in general in Purple. Mostly, the band’s ructions and fractures were sparked by Gillan and Blackmore clashing, each as truculent and unbending as the other. The singer and the guitarist were so at odds during the making of 1973’s Who Do We Think We Are album that they didn’t speak a word to each other. Gillan threatened to quit, and Blackmore contemplated prising Paice away with him to launch a new power trio.

Fearing the loss of their cash cow, Purple’s then-managers intervened. They held clandestine meetings with Glover and Lord, encouraging them to bring Paice on side and keep the band going even without their two frontmen. In the event, Gillan went and Blackmore stayed – but only on the proviso that Glover was also cast out.

“It was real stab in the back,” says Glover. “I felt Purple had let me down, but not so much Ritchie, strangely enough. He at least was honest with me. At the last gig of the tour, in Osaka, Japan, he approached me side-stage and said: ‘It’s not personal, it’s business.’ And he left it at that.

“Not long after, Purple were crowned Number One Act In America in Billboard. The magazine ran the story with a big picture of David Coverdale and my replacement, Glenn Hughes. That was like having salt put in my wounds – horrible. Probably the hardest thing I’ve faced in my life.”

Post-Purple, Glover concentrated his energies on producing, and oversaw albums for Judas Priest, Nazareth and Status Quo, among others, as well as the Ian Gillan Band’s Child In Time and two by David Coverdale: White Snake and Northwinds. In 1979, following a chance meeting with his one-time nemesis at Munich’s Musicland Studios, he accepted an offer from Blackmore to produce Rainbow’s Down To Earth. Soon after, Glover joined the band, indicating either a saint’s capacity for forgiveness or else a coolly calculating streak.

“It was a good opportunity for me, and why should I bear a grudge?” he says now. “I’m a huge Ritchie fan. Some of my biggest influences have come from him, and I can’t think of my life without him being in it, or of course Jon, Ian and Ian.”

Blackmore’s decision to dissolve Rainbow in 1983 was the catalyst for the Mark II Purple to get back together. Glover cites their Perfect Strangers as “a great moment in time, but as an album it doesn’t quite hang together”. Thereafter it was all downhill, and with Blackmore engaged in an internecine 10-year battle of wills with the others.

“That was an altogether ugly time of politics, disputes and arguments,” Glover readily admits. “I can remember George Harrison once talking to me about the Traveling Wilburys. He said the five of them would stand around in the studio and someone would say: ‘Let’s do something with a Bo Diddley beat,’ and they would all grab acoustic guitars and a song would be done in ten minutes.

“That was the kind of band I wanted to be in, but I thought I would have to leave Purple to do it. Then Steve joined us, and I found myself in a studio in Orlando one day to make Purpendicular, and literally the five of us were stood there and exchanging ideas. The band blossomed again.”

Describing himself as an incorrigible optimist, Glover, like Paice, believes Purple could carry on yet for three, perhaps four more years, and also that InFinite will not, in fact, be their final album. “It’s the old James Bond thing,” Paice says, ‘“never say ‘never’ again.”

“The record company came up with that title anyway,” Glover defers. “They’re hedging their bets. The idea of announcing a final show, like Sabbath has just done, none of us wanted that. So we thought sod it, let’s just keep going. But then no one knows what’s around the corner. It seems the fashion these days is to drop dead. Which is kind of frightening when people younger than you are suddenly gone.”

More times than he can count, Don Airey has been asked how hard he has found it to fill Jon Lord’s shoes. So often, in fact, that not so very long ago he took an actual pair of Lord’s shoes along to a press conference. Lord had left his brogues in Purple’s wardrobe, and Airey meant to whip them out and try them on when the inevitable line of enquiry came up. Of course, on that one occasion the question wasn’t asked.

It was while Purple were making InFinite last summer that Airey eventually got the opportunity to gauge the seamlessness with which he has assimilated into the band – and all thanks to an air-conditioning engineer.

“The air-con had broken in my hotel room in Nashville, and this guy came up to fix it,” he recalls. “He had no idea who I was. But I was playing back our rehearsal tapes at the time, and he said: ‘That sounds exactly like Deep Purple.’ I mean to say, I’d be very hurt if they felt they had to get someone else in now, which Paice-y is always threatening to do – in the nicest possible way.”

Sunderland-born Airey, these days resident in a village near Cambridge, has now been Deep Purple’s keyboard player for 15 years, which is more than three times longer than the Mark II line-up originally lasted. He first encountered the band when he was a student at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester, when a girlfriend took him along to see them play at a local club.

“I went in one person and came out another,” he says. “God, I’d never heard such a racket, and especially coming from Jon Lord. And that’s all I wanted to do with my life from that moment on.”

By the time he got the call to join Purple, Airey had racked up an impressive CV as hard rock’s other go-to keyboard player. Beginning in 1971 with Cozy Powell’s band Hammer, his list of credits includes stints with Jethro Tull, Gary Moore, Whitesnake and both Sabbath and Ozzy. From 1979 to 1981 he was with Glover in Blackmore’s Rainbow.

“When I was about to join Purple I braced myself for what I call ‘all the old bollocks’,” he says. “That is to say the dark moods and people turning up late, playing badly on purpose and being rude to everyone. Lo and behold, all that had gone, and it’s been a pleasant experience for everybody. The hard thing about replacing Jon wasn’t just the playing aspect. He was kind of a mentor to everyone and the life and soul of the dinner party, which I’m not exactly. I’m more of a football hooligan.”

The other ‘new man’, Steve Morse has been Purple’s lead guitarist for 22 years now. A native of Hamilton, Ohio, Morse developed his chops with 70s fusion-rockers Dixie Dregs and in the mid-80s joined pomp-rockers Kansas. His first contact with Purple was as a teenager growing up in Georgia.

“I was listening to the radio, and Purple’s version of Hush came on,” he says. “The guitar, organ and that beat were the things I remember. Later I played part-time in a covers band while composing my own weird music. We did the rock hits of the day, and Smoke On The Water was a big one for us. The first time I played it was in a bar near the little airport in Augusta, Georgia.”

Morse, presently on a vacation cruise around the Gulf of Mexico and contactable only via email, is perhaps the member of Purple racing most against the clock. As revealed in From Here To Infinity, he suffers with osteoarthritis in his right hand. The condition makes it painful for him to play and is also degenerative. Airey, meanwhile, says he’s not the man to ask about Purple’s future plans.

“Groups are funny things,” he says. “And this one’s not so much a band of disparate as desperate characters. I could be wrong, but I don’t think any of us has an exit strategy. For me the essence of Purple is the final chord of Child In Time. I’ve never heard anything like it. ”

Ian Gillan remembers Child in Time being written in ten minutes flat in 1969 and after Lord began “noodling away” at the chords to Bombay Calling, an instrumental track by San Francisco acid-heads It’s A Beautiful Day. “Highway Star was done on the tour-bus driving down to Portsmouth and we played it onstage that night,” he adds. “The best songs always take less than twenty minutes. Back then there was an explosion of ideas in the band.”

Gillan is at home in Portugal on this late-Friday afternoon. He is affable and in good spirits, but seems complex and contrary too. He claims not to be nostalgic or to keep in touch with even his closest friends, and yet just last Christmas says he hosted a reunion of his first, early-60s, band The Javelins. Also, he thinks of Jon Lord every day. The two of them kept up a ritual of doing The Times cryptic crossword together.

“He would be infuriated at the way I wrote the letter ‘D’,” says Gillan, chuckling. “Every time I write one out now, Jon grumbles in the back of my head and a little smile comes to my face. ‘Alright mate, I’m still trying to get it right.’

“We were all very close, and I guess you could describe Purple as a family going through life. The house is still standing but probably needs redecorating and the garden’s a bit overgrown. There’ve been a few divorces, illnesses and deaths along the way, but we’re still here.”

For more than half his adult life, and interrupted by spells with his own band and a brief, ill-starred tenure with Sabbath, Gillan has sung with Purple. In 1970, and after singing the title role on the album version, he turned down the lead in the film adaptation of the hit musical Jesus Christ Superstar because it would have interfered with Purple’s plans. Yet just three years later he quit the band. He left again in 1990, fired by Blackmore in favour of ex-Rainbow singer Joe Lynn Turner, who went on to make with them the doomed Slaves And Masters album, surely Purple’s lowest ebb.

It would be understandable if Gillan saw his return to Deep Purple in 1993 and Blackmore’s subsequent departure from the band as victory in their long-simmering feud. Certainly this much was suggested by Blackmore’s non-appearance at the New York ceremony to belatedly induct Purple into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in April 2016, an event that both David Coverdale and Glenn Hughes attended. Blackmore maintained he had been blocked from going by his old sparring partner, but Gillan denies the charge.

“Ritchie and I were in conflict quite a bit and the atmosphere was not pleasant at all, but the scars have healed,” Gillan insists. “Whenever Ritchie’s name is mentioned these days, all I think about are the good times. And they were sensational. He was my room-mate for years and we went on river boat holidays together. Ritchie had a great sense of humour. He liked to play pranks, and there was always some explosion or other going off. Having said all that, he was also a difficult bugger.”

Ask Gillan for his most unusual recollection from nearly 50 years of being in Purple and he recalls a visit to Russia with the band in the 1990s. “We were in Chechnya and it was the middle of summer,” he recalls. “I still had long hair and was asleep in my hotel room, lying naked on the bed. I woke to find a group of women and children standing around the bed, praying. As I raised myself up on one arm, they all shrank back, made the sign of the cross and fled from the room. They had heard Chinese whispers that Jesus Christ was in town.”

Deep Purple’s current schedule runs up to November 23, 2017 when they will end their European tour with a show at London’s O2 Arena. After coming off stage that night, they intend to board a river boat and Ian Gillan will once again sail up the Thames in the company of bandmates and their families, toasting each other with champagne. Further dates in the Far East and South America are likely in 2018, but beyond that nothing is written.

One thing, though, is for sure. And that is that Deep Purple will not go quietly into the long, black night. Whenever it is that they do bring down the curtain, they will leave behind them an indelible footprint on the landscape of rock and popular culture as a whole. They can as well be assured that someone, somewhere will always be just about to pick up a guitar and strike up that unshakeable duh-duh-duh, duh-duh-duh-duh riff.

“I think you need two things in life to be happy,” considers Gillan. “One is a sense of purpose, and the other is of belonging. For most of my professional life Purple has given me both. Ideally we will peter out like a rocket, just fizzle to earth. We’ll have run our race and now it’s time for a beer.”

Infinite is released on April 7 via earMUSIC.

Read Classic Rock, Metal Hammer & Prog for free with TeamRock+