“I’ll be honest with you - it was a very tough job when I replaced Jesus Christ as the singer in Deep Purple.”

Hold on a minute – did I hear correctly? Did David Coverdale just tell me that Britain’s greatest heavy rock band formerly employed the Son of God as lead vocalist? Was that what it meant in the Bible, when it said He turned water into whine? Did a humble headbanger from Nazareth (not Dan McCafferty) once share the same stage as Purple guitarist Ritchie Blackmore? And if so, how did His Holiness cope with Blackers’ spooky Ouija board tactics and black magic tricks?

My head started spinning – but it wasn’t long before it jolted back into the ‘stop’ position. Because suddenly I realised that Coverdale wasn’t coming on all religious at me after all. He was actually making a jokey reference to Ian Gillan who, before he was in the Purps, starred as JC on the original recording of Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s Jesus Christ Superstar musical.

Gillan joined Deep Purple in summer 1969, replacing Rod Evans and signifying the beginning of the Mark II line-up of the group. (Roger Glover stepped in to succeed bassist Nick Simper at the same time.) Four years later, Coverdale would turn up for an audition as a gauche unknown – wielding a bottle of Bell’s whisky and with his nerves jangling in time with his oversized belt buckle – and despite a total lack of experience be selected as the man to fill Gillan’s boots. (Or sandals, given the latter’s Messiah-like standing.)

Not that Coverdale was the first choice as frontman for the No.3 version of Purple. Nosiree. If Ritchie Blackmore had had his way, the lead singer job would have gone to Free’s Paul Rodgers. And just imagine: somewhere in an alternative reality, Thin Lizzy’s Phil Lynott would also be a member of the group, thrusting the slim-line neck of his bass down your awestruck gob…

Phew. This is a complicated story, so I’d better take it one step at a time. The trail of circumstances that led to David Coverdale – and also bassist/vocalist Glenn Hughes, let us not forget – becoming Purple people began in December ’72 when Ian Gillan gave notice of his intention to quit the band in six months’ time. Gillan had decided to offer advance warning so that “nobody will be able to take unfair advantage of the situation,” he stated cryptically, more than three decades ago.

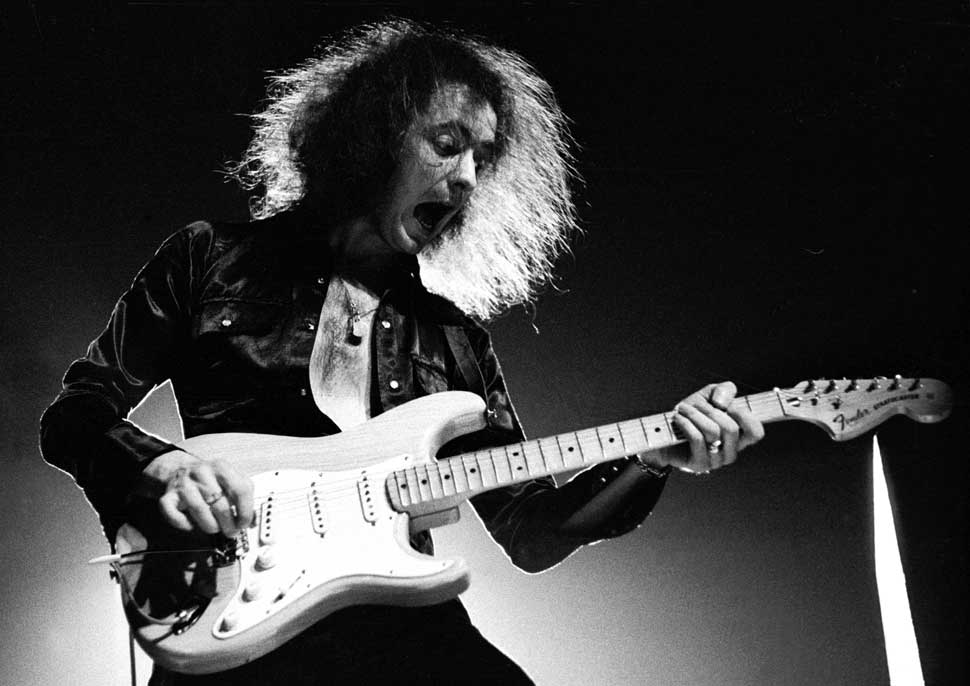

Seventy-two had been a busy year for Deep Purple: they’d recorded the Who Do You Think We Are! album in cantankerous mood, and had spent most of the rest of the time grimly ploughing the road in the US. Although record sales and concert attendances were climbing rapidly, band-member relationships were disintegrating in inverse proportion. The chief clash was between Gillan and Blackmore; they were at loggerheads, loath to even acknowledge each other’s existence. But the band’s hard work was definitely beginning to pay off: ’73 saw Purple being named the biggest-selling Billboard album act of the year.

But that was no cause for celebration in a group that was threatening to implode. Keyboard player Jon Lord, for one, moaned that Purple’s music was stagnating, while Blackmore continually sniped at Gillan and grumbled about being fed up with his lot. “I’m writing about eighty per cent of the stuff but the credit is being split five ways; I’m not getting any respect,” the Man In Black complained.

In fact, Ritchie had been the first to think about leaving when, in late ’71, he had arranged some studio time with Purple drummer Ian Paice and the aforementioned Phil Lynott. The project was called Baby Face and Blackmore talked about it openly in the music press at the time, much to Gillan’s exasperation. Gillan was further enraged when Blackmore began to tell anyone who would listen how much he admired Paul Rodgers as a singer.

Casting his mind back to Baby Face, Ian Paice remembers today: “It really came about when Ritchie and I were mulling over the idea of trying out something in a trio form. We liked the idea of a trio because it gives you a lot of freedom – you have to fill in all the holes; there’s nowhere to hide.

Paice elaborates: “We both really thought Phil Lynott’s voice was great and his whole persona was a wonderful thing to behold. So we decided to try and get something together in the studio. But the upshot of it was that, at the time, although Phil looked great and he sang great, he didn’t play the bass very well! He got better very, very quickly but to start off with he had a great deal of trouble tuning and staying in tempo.

“So we had a fun time but that really was about as far as it could go. Ritchie and I found it was very difficult, rhythmically, to actually make it work, even though the sound of Phil’s voice was great.

“I don’t know what happened, but those tapes just got lost in the mists of time – they might’ve been wiped over by the studio. But that’s all it was; we just wanted to see if we could have a bit of fun with the trio on the side. It was never meant to take the place of Purple.”

But Baby Face certainly sowed the seeds of Deep disgruntlement, and when Ian Gillan announced his intention to quit Purple a year or so after the Blackmore/Paice/Lynott sessions the singer truly thought it would mark the group’s demise: “We should quit while we’re ahead,” he insisted at the time.

That the band stayed intact – of course, being Deep Purple, such things are relative – was as much to do with management pressure as anything else. With Gillan on his way out (his final DP Mark II show was in Japan on June 29, ’73) and with Blackmore and Paice still apparently making noises about wanting to develop the Baby Face project with Lynott – and maybe even bringing Paul Rodgers on board as well – Purple’s management made a covert approach to Jon Lord and bassist Roger Glover.

They asked the duo if they’d be interested in keeping Deep Purple going minus Gillan, Blackmore and Paice, but with three brand new members. Lord, for one, hummed and ha’d; he had already been weighing the options of quitting Purple to join up with his old mate Tony Ashton, of Ashton, Gardner & Dyke and Resurrection Shuffle fame… but that’s enough Jesus Christ connections!

In the meantime, such was the grind of the rumour mill that Thin Lizzy’s management were forced to issue a denial to the press, saying that Lynott had absolutely no plans to record with Blackmore and Paice again. But still the Gene Simmons-sized tongues wagged. And dribbled, no doubt.

Lord and Glover eventually agreed with their managers to examine the possibility of maintaining Purple as a going concern. But there then unfolded an intricate chain of events that saw Glover being frozen out of the Purple powerbase, Lord switching his allegiances, and Blackmore and Paice looming back into the frigid frame.

The pivotal moment came in April ’73 when, back playing a series of hastily arranged dates in the US, Ritchie, Jon and Ian Paice caught a show by fast-rising British three-piece Trapeze, at the Whisky A-Go-Go in Los Angeles. Jon and Ian had been tracking Trapeze, their interest centring on the band’s mightily impressive bass player, Glenn Hughes, a self-confessed “strapping young northern lad with a tight arse” from Cannock, Staffordshire.

With Ritchie’s approval, it was decided to move in for the kill. In May, at another Trapeze show back in London, Lord asked Hughes if he’d be interested in joining a new-look Deep Purple. But Glenn said he wasn’t interested and preferred to stick with his Trapeze bandmates.

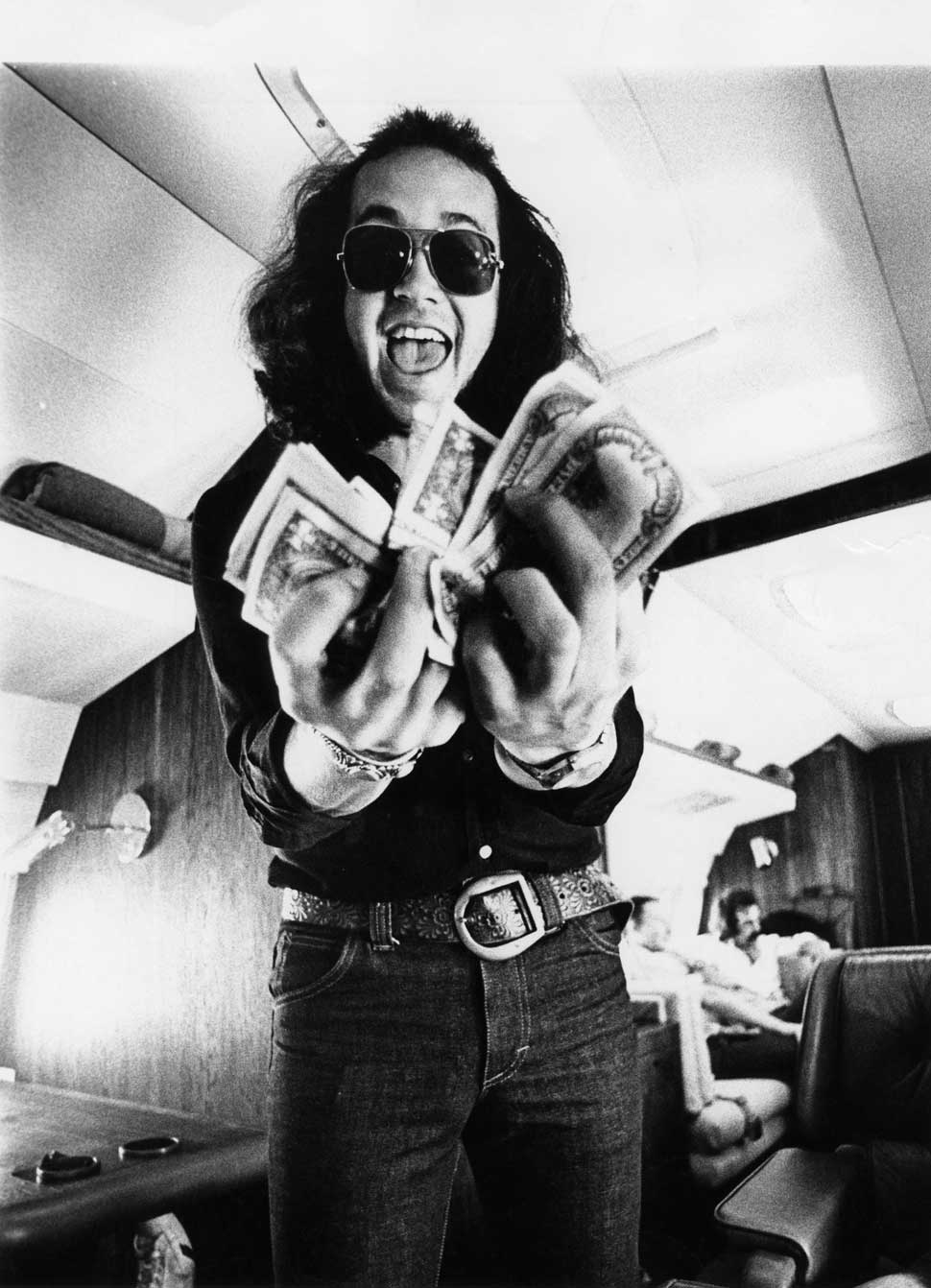

“In seventy-three my band Trapeze were just about knocking on the door,” Glenn Hughes recalls. “We were selling out five- to eight-thousand seaters in the southern states of America, our US label London Records – who also had ZZ Top at the time – were going to up the stakes and do a lot more marketing and promotion for us… we were on the verge of something big; we were doing really well.”

What made Glenn change his mind and join Purple was both the lure of the filthy lucre (“Smoke On The Water was the biggest tune around in the US; I suddenly saw lots of money”) and the prospect of being in a band with Paul Rodgers.

“I had become friends with Jon Lord and Ian Paice, although Ritchie Blackmore was dark and mysterious and I didn’t know what to make of him,” Hughes chuckles. “Anyway, I saw Purple play at New York’s Felt Forum and they were great. They told me about Ian Gillan leaving, and they said they were looking at getting Paul Rodgers as his replacement… and when they told me about those plans, maybe that was the decisive thing. I was in awe of the prospect of getting to sing with Paul Rodgers. I’m sure David [Coverdale] wouldn’t mind me telling you that.”

Another problem, says Hughes, was that he found it “hard work getting in a Purple frame of mind – it was too basic rock for me. If people revisit [Trapeze’s classic third album] You Are The Music… We’re Just The Band, they can listen to the shift in gear from [second album] Medusa and see how soulful things were becoming.

"When Purple first offered me the job, I was in a very, very different frame of mind as a musician. If you listen to [Trapeze] tracks such as Coast To Coast and Will Our Love End, I was actually following a very rootsy course. I’m not knocking Purple because obviously it’s done me well over the years; it’s just that, for me, I was moving forward in another direction.”

Ian Paice expands: “There were plenty of decent bands around at the time, but only a few musicians were really very, very good. Glenn obviously had one of those voices that stood out – but it wasn’t a sound that Ritchie saw as being a lead voice for what he had in mind. So, good as Glenn was – and he was and still is a great singer – it wasn’t something Ritchie felt he wanted to write music for.”

But Blackmore was keen on Hughes as a bass player as such?

“As a bass player, yes,” confirms Paice, “and as a backing vocalist … well, backing vocalist is not the right term, that demeans it too much, but as another sound. Ritchie felt that after Ian, which was very much a rock’n’roll voice, he didn’t want to go the soulful route which was Glenn; he was looking more toward a bluesy sound. A much lower, male-timbre type voice.”

Hughes endorses Paice’s comments: “They must have known and seen that I was a lead-singing bass player – I think Ritchie might’ve been the only one to have had reservations. Truth be known, Blackmore wanted Paul Rodgers one hundred per cent; he wanted him to be the lead singer in Deep Purple – and having me as a bass player who could also sing something would have been strong sort of bonus.”

He reflects: “But whatever did or didn’t happen, you cannot take away the talent that was in the new band – the five of us on that particular album [Burn] were firing on all cylinders.”

But we’re getting a little ahead of ourselves here. Let’s return to Roger Glover, who abruptly found himself out in the cold, a victim of one of Ritchie Blackmore’s notorious mood-swings. Somehow sensing that he was being slyly nudged out of Purple, Roger confronted band co-manager Tony Edwards, who told him Blackmore had changed his mind and had decided to stay on as guitarist in the band after all – but on the proviso that Glover left. Roger was flabbergasted; he had no idea he’d done anything wrong.

“Why is this happening? What have I done?” he protested. “I’m not going to get pushed out; I’ll leave instead.” (But Glover didn’t break away completely: he took over as head of A&R at Purple Records and, in the short term at least, concentrated on record production.)

Despite Ritchie’s machinations, his masterplan failed. Singularly unimpressed by rumblings in the music press that he had agreed to join Purple (he had only consented to “discuss it”), Paul Rodgers turned down the band’s kind offer.

“We did ask Paul if he wanted the job,” Ian Paice validates, “but he was just starting up with Bad Company at the time, so that idea didn’t last very long.”

If Bad Company hadn’t happened, how do you think Rodgers would’ve fitted into Purple? Would it have worked?

Paice responds drily: “Until the first fight, yes.”

So Rodgers turned you down – did an element of panic creep in at that point? “No,” insists Paice, “we just realised that it wasn’t worth rushing around. Maybe it was on the cards that we would find somebody new. And that’s basically what happened – we started advertising in all the music press, and hundreds and hundreds of tapes started coming in.

"Nobody knew which band it [the singer vacancy] was for, because we didn’t say it was for Deep Purple, but everyone got a clue from the timing. So people had an idea that if they were going to send a tape in, then it might be coming to one of us.”

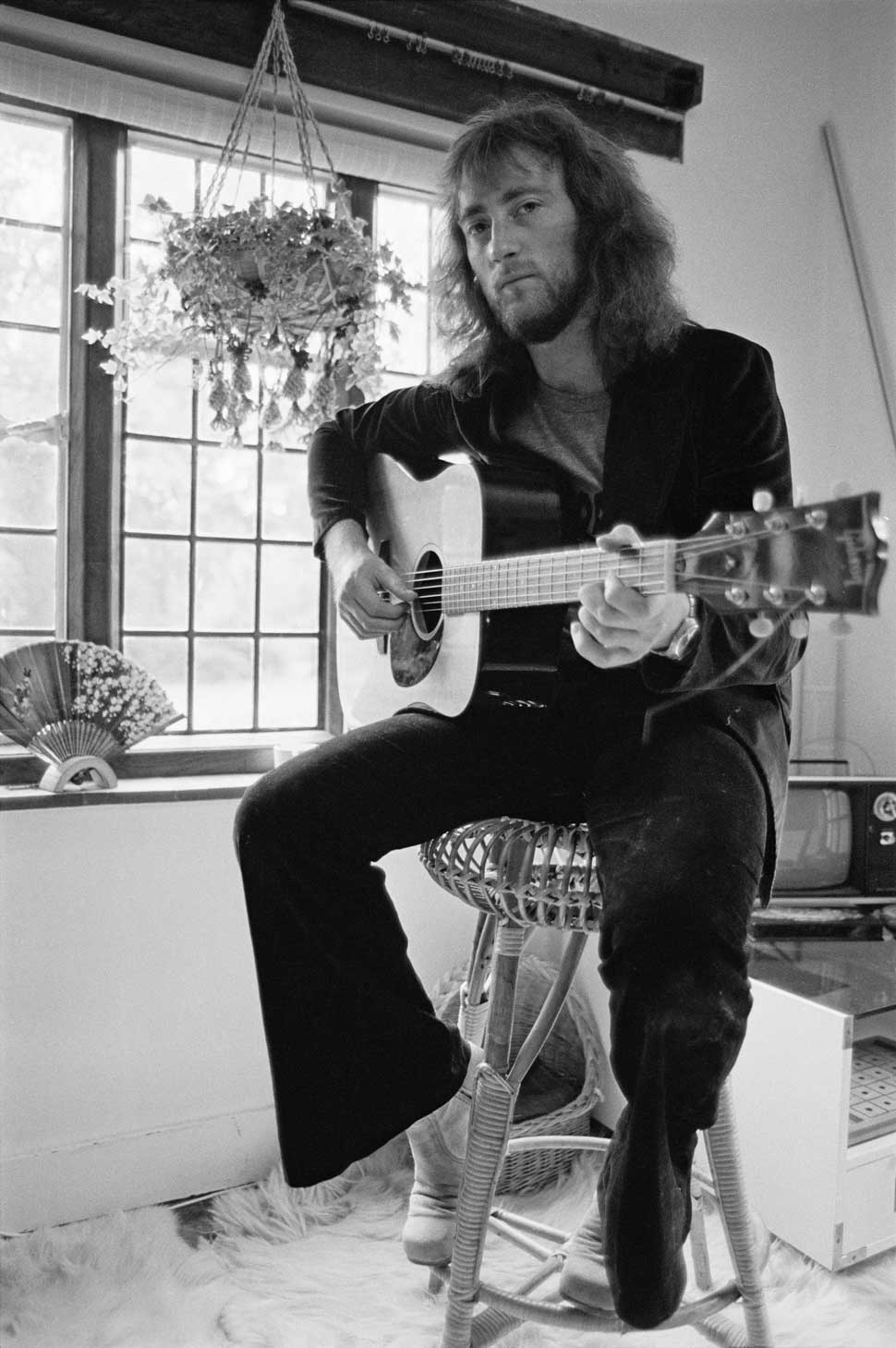

Enter a raw, untried 21-year-old singer called David Coverdale from Marske-by-the-Sea, Cleveland, Yorkshire. He decided to give it a shot as Purple’s new singer, packaged up a demo tape and sent it down to the band’s London offices in Newman Street. Coverdale also enclosed a photo of himself… as a skinny kid wearing a boy-scout uniform!

“The photo was in a frame on my mother’s mantelpiece,” David reveals. “I didn’t have a proper picture, that was the bottom line, so when I sent the demo tape off, it was with a kind of Yorkshire, oh-fuck-you attitude. I was just hoping to get the photo back; otherwise my mother would have been seriously miffed.”

Ian Paice remembers Coverdale’s tape vividly: “It was bloody awful!” he exclaims. “There were four songs on it and David basically sounded like Scott Walker. He was singing in that very… well, Scott Walker style. You can’t put it any other way.

“But there was this one song where he just jumped up an octave, only for three or four bars, mind you, and his voice started to happen. I just thought – well, there’s something there, you know. I thought there was enough there to get him down and check him out.”

Coverdale’s Deep Purple audition took place in mid-August ’73, at Scorpio Sound Studios in Euston, London; he was uptight and fuelled with liquor.

Paice reminisces: “When David turned up, you’re talking about a guy who had been working in a clothes shop in Redcar [the wonderfully named Stride In Style’ boutique] suddenly being in the position of maybe getting a job with a very successful band – so he was extremely nervous. And also presenting yourself in a clothes shop is not the same as presenting yourself on a stage.

“So David was overweight, he had a rather strange haircut, very weird clothes and a moustache that did him no justice whatsoever. But all that aside, what we were looking for was the voice; everything else we knew would sort of fix itself. And obviously David was very anxious and on edge: he came in brandishing a half-empty bottle of whisky, but we just did some studio stuff, and let him relax and wail away.”

Of the Scott Walker comparison, Coverdale says: “Oh that’s funny – Jon Lord would also say that to me. Part of our bar act was to do Joanna [Walker’s ’68 hit], that was one of our little party tricks. We also used to do the Burn song in, like, waltz time – and I’d do my ‘Whispering’ Paul McDowell from the Temperance Seven thing, but I don’t think you’re old enough to remember that…”

Coverdale doubts that his was the worst tape Purple received: “Paicey told me that one demo was of a guy playing one finger piano on Black Night. Ian said it was just so bad he was cracking up, and the letter that came with it said: ‘Dear Deep Purple, I’m not very good-looking but my mam thinks I am.’ So it went from there to some very well-known artists, apparently.”

But half-arsed Scott Walker impressions or not, Purple knew they had found their man: “You know we only auditioned one singer; do you know that? We only auditioned one singer – and it was David,” says Glenn Hughes, making a surprise disclosure. “Bloody hell. I don’t know if anyone’s told you this, but nobody else was ever seen on an audition. So I never really ever got to hear any of the other demo tapes – I think the rumour was that there were hundreds; I’m not so sure about that.

"But all I know is that Ritchie Blackmore wanted Paul Rodgers and he couldn’t get him. However, David was a Yorkshireman and Rodgers was also from that neck of the woods [Middlesbrough]… I think you know David was a little bit influenced by Free; you can hear that in his voice. That’s not a bad thing because Paul Rodgers is a great singer, and I think we got it right with David.”

Despite his audition jitters, Coverdale claims he didn’t feel the weight of Purple’s heritage: “No, not at all. Lads from Yorkshire don’t have that. I was never made to feel less than welcome by anyone other than by elements of the management – the band never asked me to recreate this song, or to do this or that.

"I would have been very happy to have done Child In Time but they were, oh no, let’s leave that and move on. The band were marvellous to me; I couldn’t have asked for a better introduction into that madhouse. At the time, I had absolutely no idea how incredibly global and huge Deep Purple were.”

David elucidates: “The weirdest thing is that when I started to crack America [with Whitesnake] hardly anybody knew I was in Deep Purple. Of course there was a huge lack of homework on the part of journalists I would talk to – and I was quite happy just talking about the ’Snake.

"But it was always a surprise for me to get back to Europe and the first question somebody in Romania would ask would be [adopts bizarre Eastern European accent]: ‘Zo Davi-i-id, how vaz it in Deep Po-o-orple?’ Because in the US Led Zeppelin were like the Pope, but Purple were the Pope in Europe. That was always fascinating to me.”

After coming under Purple’s scrutiny (most notably the steely-eyed Blackmore’s), Coverdale was driven back to the train station by Ian Paice. “That was when I bought my first-class ticket back to Darlington,” laughs David. “I treated myself. I came home and there was a streamer over the door of my first-floor flat, saying: ‘Welcome home, superstar.’

"And then of course I never heard anything for days; I could’ve fucking killed them. I started to make excuses to my friends. I told them: ‘Well, I’ve been thinking, you know, Deep Purple aren’t really my cup of tea…’ Ha-ha!”

Coverdale was formally offered the position of Purple vocalist a week after his audition – the longest seven days of his life.

“We didn’t think it was too much of a risk, employing a complete unknown,” stresses Ian Paice. “It was always fairly well calculated and considered. We believed that there was enough in David’s voice to be individual and to be able to stand up in its own right. And because David’s singing was so different to Gillan’s, there could be no comparison. It wasn’t like trying to replace an Ian with another Ian.”

Purple rode out the jibes from the music press that they’d lost their marbles and stupidly employed ‘a singing salesman from Redcar’. But the band did recognise that Coverdale wasn’t the slimmest of guys and needed to shed a few pounds – fast. David was prescribed a course of ‘slimming pills’ from (as he puts it) “a very accommodating Harley Street doctor”.

Coverdale grumbles: “It was horrible. I’ve never enjoyed amphetamines… basically those kind of things [slimming pills] are amphetamines; they speed your system up so as not to desire food. So I was wired out pretty much all the time, while we were making Burn. Actually I recently saw pictures of me back at the beginning; I didn’t actually look that bad and I think it was [co-manager] John Coletta’s paranoia.

"Because Ian Gillan was regarded as such a beautiful man, they just wanted to make sure that I got this caterpillar shaved off my top lip. I also had, like, a mad Edgar Broughton hairstyle in those days, so they needed to get me groomed up a little bit.”

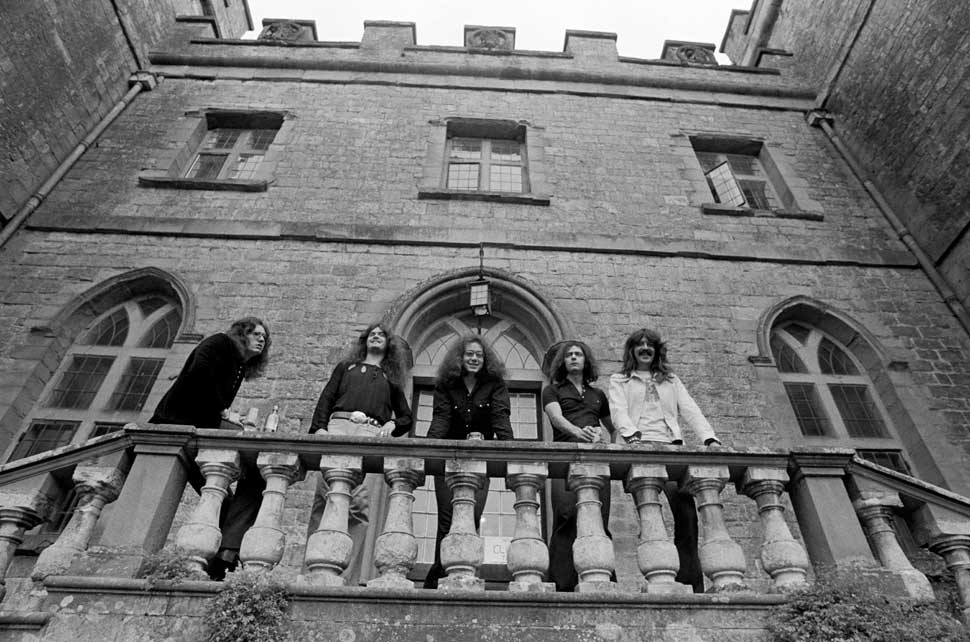

On September 9, ’73, the new-style Deep Purple began two weeks of writing and rehearsals at Clearwell Castle in Gloucestershire. Coverdale was officially unveiled as the band’s new singer at Clearwell on September 23, the day after his 22nd birthday. Later, on November 3, the band flew to Montreux, Switzerland.

They commenced recording what would become the Burn album on the 8th, using the Rolling Stones’ mobile and working with the regular Purple engineer, Martin Birch. The band made rapid progress, laying down practically a song a day, and then returned to the UK for mixing duties at Ian Gillan’s studio, Kingsway Recorders.

Burn ushered in an exciting new direction for Purple and the two new members, David Coverdale and Glenn Hughes, made an immediate impact. The former brought a strutting soulfulness; the latter offered an edgy funkiness – and to round it all off, the pair perfected some intricate vocal interplay that took the band to new heights, firmly setting Burn apart from recorded achievements with Ian Gillan as the lone singer in the Purple line-up.

“I just felt so at home on Burn,” says Hughes, “particularly on the more, if you like, groovy tracks such as Sail Away. When David and I sang that song – and of course you know he sang the first verse and I sang the second, and we carried on from there – I think it signified the two different singers: David being the lower, bluesier tone; Glenn Hughes being the sort of soulful, upper-register guy. I think that signified the dual lead-singer thing.”

“Initially it was fairly controlled,” clarifies Ian Paice, “because there’s certain ways that new boys act that old boys don’t. As new boys, they [Coverdale and Hughes] were very, very much, er… well, they did as they were asked. And whether they actually always agreed with it one hundred per cent, they still did as they were asked – because that’s the way it was, you know.”

Where does Burn fit into the overall Purple package? Do you regard it as one of the band’s best albums?

“I regard Burn as having some very, very good tracks on it – and I think as a departure from the Mark Two line-up it was strong,” Paice replies. “It wasn’t trying to be the son of Machine Head or the son of In Rock; it was a statement of its own. I think that alone was quite a brave thing to do, and that alone makes it stand up.”

Was it a liberation for you, as Purple’s drummer, to be able to play in a slightly different, funkier way?

“It was another thing to be able to try – because rhythmically it’s interesting. You can get sort of stereotyped by your own band, when all of a sudden you’re playing stuff that you know you’ve played before, but you can’t think of anything else to play because… you know, that’s what it is. So when a different idea comes up, you can start falling in with it. Yes, those were enjoyable times.”

There are some intriguing stories behind the genesis of several of the album’s songs. The title track, for instance, almost had the prosaic moniker of The Road.

“You can tell my stuff: it’s got blues-based lyrics, as it continues to have… but there’s another version of the Burn song that always makes Lordy crack up whenever we bump into each other,” cackles Coverdale. “I’d written a whole version of this song called The Road. It went [sings ear-splittingly]: ‘Take me do-o-own the RO-O-O-O-AD!’ So Lordy and me, when we meet up, we still fucking crack up about that.

"But the lyric was really good; it was all very bluesy, I was going back to the place I was born with an empty suitcase and bollocks well-worn, or whatever… it was a good lyric, but of course the favourite was Burn and that ultimately became the title of the album.”

For stand-out track, the monstrous, brooding Mistreated (a song that would transcend Purple and later become the high-spot of future live shows by Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow and Whitesnake), the two ‘new boys’ recorded a booming choral section that failed to appear on the final version of the song. Blackmore complained that his guitar was being swamped and had Coverdale and Hughes’s work wiped.

“Ha-ha! That’s always the lament of somebody who thinks their instrument is more important than anyone else’s,” chortles Ian Paice. “At that moment in time he [Ritchie] may have been right, I don’t know, but one thing is for sure – on Burn, the vocals did start to take up a lot more room. You only have one hundred per cent of the sound and if one thing is bigger, then another thing has got to be smaller.”

Ultimately, Mistreated became the only song on Burn to feature Coverdale singing lead vocals on his own.

Referring to Ian Gillan and the Machine Head song, Space Truckin’, David adds: “It was never really up my alley to sing, ‘We had a lot of fun on Venus’ – unless I’d known someone personally called Venus, of course. So I felt Mistreated was a super direction and Ritchie really got his teeth into it. Glenn and myself did our big vocal thing and it just sounded spectacular. It was epic. But Ritchie was absolutely correct that you couldn’t hear the guitar if you had the voices too featured.”

Elsewhere, the loping, juddering rhythm to Sail Away was influenced by Stevie Wonder: “I was actually listening to more Stevie, Sly And The Family Stone and Donny Hathaway than hard rock in those days,” says Coverdale.

Paice grins: “The groove is pretty good – it was some time after Stevie Wonder’s Superstition and we liked the feel of that song and the way the riff just rolled over. That was probably an inspiration for it.”

Showing that, contrary to popular opinion, Purple definitely did have a sense of humour, Lay Down Stay Down had the working title, Shit Fuck Cunt Wank.

“It was actually a little more refined than that: Shit Fuck Cack Wank,” corrects Coverdale. “[Sings even more ear-splittingly] Shit, fuck, cack, W-A-A-A-NK! Thank you for ruining my Shakespearean reputation. Then again, I did write Slide It In as well. But yes, Glenn Hughes and I would wrap our golden tonsils around those swear-words throughout rehearsals until I came up with Lay Down Stay Down – wherever the fuck that came from. I suppose it was like all those Elvis lyrics, looking for trouble and stuff – that was a cracker.”

“Coming up with the right nouns and vowels for that bloody chorus to Lay Down Stay Down was kind of difficult,” affirms Hughes.

Burn closes with an instrumental number, A200, which – it turns out – is a code for ‘critter cream ointment’.

“If you’re unfortunate enough to catch the critters [crabs] wandering about your nether regions, that’s the stuff you had to put on it,” winces Paice. “If you happened to get a little bit of infestation, then that would be the stuff.”

“It was like a shampoo that people would use in America many years ago to get rid of pubic critters,” Coverdale groans.

“It was Lordy’s idea to come up with the title,” maintains Hughes, neatly sidestepping responsibility.

Burn was originally released on February 15, ’74; it rose to No.3 in the charts in the UK and gained a No.9 position in the US. My final question to Messrs Coverdale, Hughes and Paice was: does it seem like 30 years ago?

David: “Breathtaking, isn’t it? But you were there back then too, Geoff. You were a skinny little kid, if memory serves – all neck and glasses. Plus there was [occasional Classic Rock contributor] Pete Makowski. And [photographer] Ross Halfin – he was about four, wasn’t he? The camera was bigger than him. I’m so blessed in my life; I’m really happy that those things happened.”

Glenn: “It’s a lifetime ago. But life was simple, and it was a great, fun time. I wouldn’t trade it for anything. It’s made me – all these years later, after all the things I’ve done in my life… it’s made me the person I am now. So I can’t complain.”

Ian: “I’ve been trying with some difficulty to remember the things that happened when you’ve been asking me your questions – so yes, it was a bloody long time ago. But then again, I’ll probably put the Burn album in my CD player after I’ve finished talking to you. And listening to it, it’ll seem like yesterday.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 72, published in November 2004. Deep Purple are on the cover of the current issue of Classic Rock.