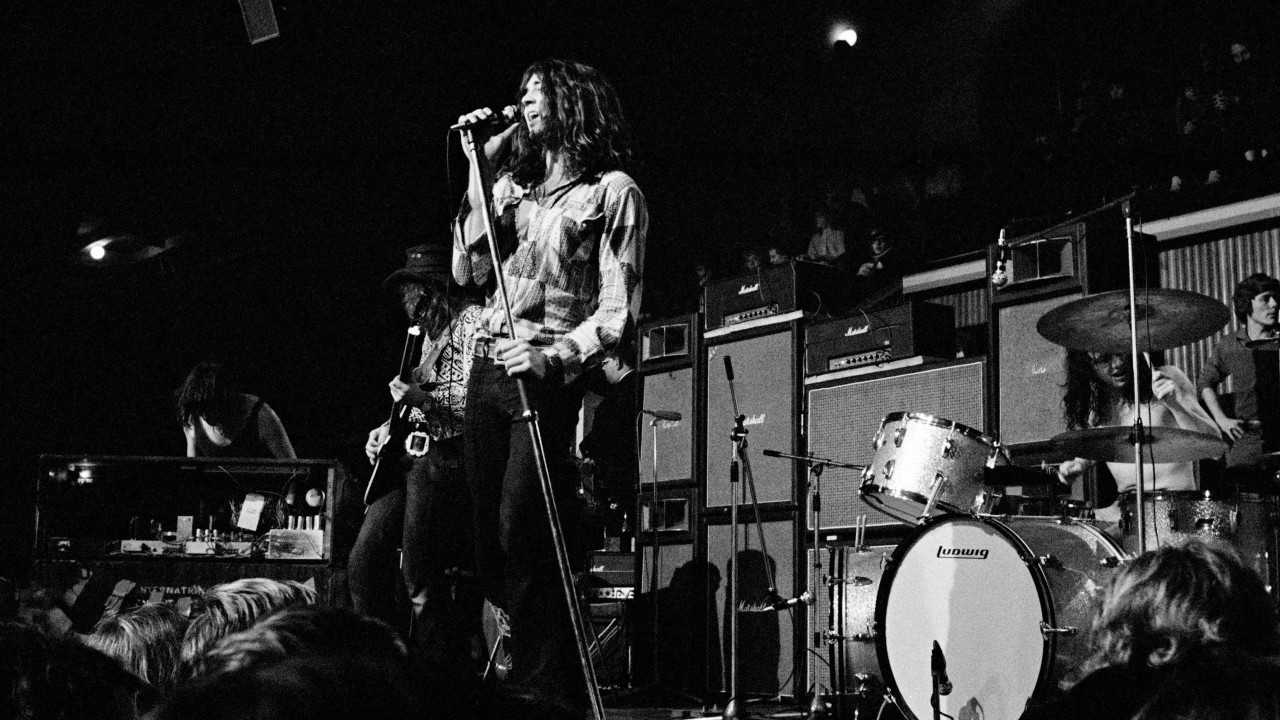

Osaka, August 15, 1972. In the Kosei Nenken Kaikan concert hall, Deep Purple are playing their first ever show in Japan. Over the past three years, the stage has become their home. It’s not just the non-stop touring – this year alone they’ve already completed four North American tours, two European tours and several UK dates. It’s because the stage is the place where Deep Purple – and specifically the MK II line-up – really stake out their turf, where they define their musical identity.

The band learnt long ago that there was no point in rehearsing for shows. As soon as they get on stage, routine flies out of the window. With guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, keyboard player Jon Lord and drummer Ian Paice regularly veering off-piste, things would happen that weren’t planned – often amazing things. Not tonight, though.

Used to the uninhibited antics of Western audiences blitzed on green weed and red wine, the band have suddenly become strangers in a strange land. There is a deafening round of applause as each of the band members walks casually onto the stage, only for it to stop dead before they even get to their instruments. Over the years, Japanese audiences would become notorious for their restraint, but in 1972 nobody knew this. Least of all Deep Purple.

The show starts much earlier than they are used to. It’s barely six o’clock when Ian Paice’s rat-a-tat beat joins Jon Lord’s tra-la-la-ing Hammond organ that signals the intro to set-opener Highway Star, prompting another burst of polite but brief applause. Even the hard-to-impress Ritchie Blackmore appears baffled as he curls his black-clad form around his white Stratocaster and stares in disbelief at the audience. But there is another reason why Deep Purple are struggling to kindle their fire tonight: they are recording the show.

“We’d never done it before,” says bassist Roger Glover, speaking from his home in Switzerland. “In fact we had no idea what we even sounded like, only having listened to very poor quality bootlegs before. We just didn’t have the fireworks that we normally did – thinking we better not make a mistake.”

Four decades on, you can still hear the stress in his voice. Fortunately there’s a safety net: they are taping their second show at the same venue the following night. This time there’s no room for error.

“We didn’t care anymore,” says Glover. “We just forgot about it and let fly. Which is why most of the stuff on the album comes from the second night.”

The album he’s referring to is Made In Japan, the momentous double live record released later that same year. Now regarded as one of the all-time great live rock albums, it also marked a watershed moment in the history of Deep Purple: a peak of performance that, paradoxically, found the band teetering on the brink of self-destruction. By the time Purple had reached Japan in August 1972, the heady blend of huge success, clashing egos and questionable management had created what Ian Gillan calls “a chaos effect”, triggering irreparable fractures within the band.

“We all met up at the right age and the chemistry was perfect,” says Gillan. “But the one thing you’re never prepared for is success. Suddenly so many other elements come into it, particularly those things affecting your personality and character, and consequently the character and blend of the group.”

One man watching things unravel was tour manager Colin Hart, who was with the band in Japan. He had a ringside view of the Mk II line-up’s rise and fall. “It was a fantastic time,” Hart says now. “They were riding this crest of a wave, hugely popular, selling out everywhere. Probably one of the best years I’ve ever toured, in terms of sheer excitement. Then suddenly it all just… turned to shit.”

Nobody outside the group had seen it coming. Indeed from the moment Gillan and Glover had arrived in June 1969 – replacing original singer Rod Evans and bassist Nick Simper – Deep Purple’s career upswing had appeared unstoppable. The band’s fourth studio album, In Rock, positioned them alongside Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath as one of the Holy Trinity of bands who were forging the new, steel-plated sound that would define the early 70s. Nobody had thought to call it heavy metal yet. This was simply rock without frontiers; heavy, certainly, but metaphorically as much as figuratively, with lots of virtuoso light and shade in among the titanic riffs, operatic vocals and bludgeoning percussion.

“There was no genre,” says Gillan. “There was no framework. You could just go where you want.”

And Purple went exactly where they wanted, especially on stage. Their live performances sat part way between Zeppelin’s ability to scale new heights of improvisation and The Who’s no-holds- barred showmanship – gigs would often climax with Blackmore smashing his entire guitar and amp set-up.

“We contrive to get an audience going – strive for a reaction,” the guitarist boasted in a 1971 interview. “I think that is a great deal more honest than walking on stage with the idea that you have to do nothing else, but stand there and play because you’re the world’s greatest musician.”

Witnessing Blackmore’s destructive displays, it was hard not to wonder if he was taking out his frustrations with his bandmates. Deep Purple had always been a combustible clash of personalities, and the arrival of Gillan brought another formidable ego into the mix. By the time of 1971’s _Firebal_l album, tensions between the livewire singer and the more conservative guitarist were becoming apparent.

“I don’t know if I’d say they didn’t like each other,” says Ian Paice. “They’re just chalk and cheese.”

“Ian Gillan is a man of the earth, he’s a salt,” says Roger Glover. “He’ll take his clothes off and jump into any river. Which is the antithesis of Ritchie Blackmore’s form of behaviour. With _Firebal_l Ritchie had ideas in mind for melodies that Ian wouldn’t or didn’t sing. Ritchie got very frustrated with that. He wanted to be more in control. But it’s supposed to be a democratic band, and it’s difficult to be in control unless you become a dictator. Which I guess is…” The bassist pauses and takes a step back.

“Ritchie’s always been true to himself first and the band second. It’s actually a strength as far as he’s concerned. And if you get to tag along, then you’re lucky. For a while.”

Glover took on the role of mediator between the two men.

“Roger used to try to be the peacekeeper,” recalls Colin Hart. “He would get very, very worried when things weren’t going right, more so even than management. Roger would take it to heart.”

The growing clashes indicated that Deep Purple’s next album was a car crash waiting to happen. It certainly got off to an inauspicious start when the original sessions for the album planned for November 1971 had be cancelled after Gillan came down with hepatitis halfway through a US tour. Having decamped to Montreux to record, disaster struck again when the casino complex they were based in burnt down during a Frank Zappa show [an event that provided the inspiration for Smoke On The Water]. Machine Head would eventually be recorded in the freezing, closed-for-the-season Grand Hotel on the outskirts of Montreux, using the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio. Astonishingly, the adversity actually brought the band closer together.

“It was all of us against the world,” says Glover. “So there was a great feeling of camaraderie on that album.”

Released in March 1972, Machine Head gave Deep Purple their first US Top 10 album, and would stay in the US chart for two years. By the time the band flew out to Japan a few months later they were at their commercial and artistic zenith.

“We had the confidence that being a big band gives you,” says Glover. “There was always the feeling that we didn’t want to follow anyone. If you follow someone, then you’re second-best. If you’re gonna be into this for the music, you have to just do it your way regardless. That’s what gives a band true fame, and that’s what we were after.”

As it turned out, the success of Machine Head amounted to little more than a sticking plaster over problems within the band. Their debut Japanese tour had been booked for August 1972. But before that they had been scheduled to start work on their next album at a sunny villa just outside Rome. At least that was the plan. Today Ian Gillan grits his teeth when talking about the sessions.

“Here were are, sitting in the middle of summer in this steaming building in Italy with no air conditioning, and Ritchie just didn’t bother turning up,” he says. “We were just sitting there for two weeks. He then turns up, and we find he’s on the other side of town in a different hotel, and he will decide when he wants to come across and who shall be in the rehearsal room and blah blah blah. By this time the megalomania had gone through the roof.”

During the three weeks they were there, the band recorded just two songs, only one of which would eventually be used on their next album – as the backing track for what would eventually become Woman From Tokyo. This tense atmosphere was still in place a few weeks later when the band boarded the plane to Japan. When they touched down, they quickly realised how different the country was – the closest they had to a bonding experience.

“It was very humbling,” Gillan says of that first visit. “I learnt so many things on that tour that it suddenly opened my eyes. Like the whole principle of bowing and courtesy and humility as an uplifting experience for yourself, and not the subjugating of yourself to others. It’s something that the West misconstrues completely. I just thought it was amazing. The tea ceremony embodies all of this. Was it anything I expected? It was unbelievable.”

They also encountered other, less salubrious customs. It was still the days of the bathhouses – or ‘soaplands’, as they were called – where visiting rock bands would be entertained by kimono-clad Geishas who brought their own special interpretation to the term ‘body wash’. [The bathhouses were closed to non-Japanese after the onset of Aids in the early 80s.]

“There were certain clubs which, if you were a visiting rock band in town, made you kings for the night,” says Gillan. “Plenty of girls around.”

“I took great advantage of those offers from the promoter, Mr Udo,” Colin Hart says with a chuckle. “Anyone who wanted to go from the band and crew, he took care of it. It was dinners and bathhouses. It was quite a respectable thing to do, you know? The women would come in and parade around in front of you in the lounge. It was superb.”

“There was a lot of fun,” concedes Glover. “The other thing, of course, was you could go to the international arcade and buy cameras cheap. We all came back laden with lenses and cases and God knows what. But the beauty of it was everyone was so nice and kind as well. I remember going back to England and going to an Italian restaurant and having a conversation with the owner and saying I’d just come back from Japan and that it was fantastic. And she nearly threw me out, because her husband had been a Japanese prisoner of war and couldn’t imagine anyone liking Japan.”

But Purple weren’t there just to enjoy the perks of Japanese culture. There was also work to do, in the shape of two gigs in Osaka and one at Tokyo’s fabled Budokan hall. When their international label, Warner’s, had initially approached them about making a live album for Japan in order to capitalise on the increased interest in heavy rock music sparked by Led Zeppelin’s first visit there the year before, the band were sceptical.

“We said we’d only do it if we could control it,” drummer Ian Paice says. “And as long as it only came out in Japan. Then when we listened back to the tapes we thought, ‘Hang on, we’ve got something here…’”

Mixing the album with engineer Martin Birch, they decided to keep it as clean and free of studio trickery as possible. According to Glover, there was just one overdub added on the entire album.

“It was at the end of the first big crescendo in Child In Time, where the music stops and there is absolute silence for a moment,” the bassist says. “We thought, ‘That doesn’t sound very live,’ so we added a moment of audience noise. But the rest was all exactly as we played them at the shows.”

Listening back to the finished album, they realised it would be foolish to limit it just to the Japanese market.

“We told the management: ‘This is really fucking good. We want it out now, we want it out everywhere!’” says Glover. Ironically, the album’s title was an underhand dig at the Japanese culture that had inspired them. At the time, Japan was still rebuilding after the war, and its industry was synonymous with cheap and trashy products such as imitation cameras and watches.

“In England at that time, the label ‘Made in Japan’ stood for something really cheap and trashy,” Gillan says sheepishly. “The title was our little amusing take on the phrase. We assumed that what we were doing was cheap and trashy, because it was only a live album. Everyone told us it was a waste of time.”

In reality it was anything but. When Made In Japan was released in Britain, in December 1972, it was a revelation. There had been momentous live albums before: Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! by the Rolling Stones; Live At Leeds by The Who – but these were single LPs; glorified stop-gaps, highlights packages that weren’t viewed in the same light as the lofty studio albums. There had also been occasional live tracks included on studio albums, most notably by The Faces and Cream. There had even been live double albums before. The previous year had seen the release of both Humble Pie’s Performance: Rockin’ The Fillmore, featuring extended jams on covers of songs by Dr John, Muddy Waters and Ray Charles, but just one original number, and the Allman Brothers Band’s At Fillmore East, a brilliant evocation of an up-and-coming band that became its breakthrough. Made In Japan, however, was the first time a truly international heavy hitter had made such a bold musical statement, and at such a pivotal moment in its career, just as its star was reaching the apex of its commercial ascendancy.

It became arguably Deep Purple’s most lasting musical statement. A faithful representation of their live show, what made it so extraordinary was that it actually improved on what were already seen as landmark tracks. Play any of the Made In Japan tracks – whether it was the crescendo-filled Child In Time, a version of Smoke On The Water that found Blackmore teasing the audience with that riff, or the 20-minute version of Space Truckin’ that filled the whole of side four – next to their original studio versions and it’s like going from black-and-white TV to colour. This was original material played not by-the-book, but taken to new, dizzying heights: longer, faster, more far-out. Listening to it in 1972 as a teenage head, rolling your first joints on its gatefold sleeve, it brought home how far music had moved beyond the confines not just of verse-chorus pop but also of the old two-sided vinyl paradigm.

In an era defined by the virtuosity of such off-the-scale players such as Hendrix and Clapton, and full-spectrum ensembles like Zeppelin , The Who and Yes, Made In Japan suddenly came to represent the apotheosis of what rock could do, where it could go and what it might still yet become. What we didn’t know was that virtually the same week Made In Japan was released in Britain, Ian Gillan had written his letter of resignation from the band. He handed it in on December 7, 1972, after Purple played a sold-out show at the Hara Arena in Dayton, Ohio, supported by Fleetwood Mac and Blue Öyster Cult.

“And I didn’t get a reply,” he says now. “Not one phone call or reply, from nobody. They must have thought, ‘Thank God he’s going.’ So I thought, ‘In that case, I might as well’.”

Ask Roger Glover and Ian Gillan what kind of person Ritchie Blackmore was in the early 70s and you get two very different opinions.

“Ritchie’s always been edgy,” says Glover. “He always makes you think he knows something you don’t, or that he’s judging you badly in some way. When he walks in a room the atmosphere changes. But that’s his magic. When he walks on a stage you can’t take your eyes off him. He’s just one of those people that has an aura about him. And he’s always had a mischievous sense of humour, practical jokes and mayhem. He likes mayhem.”

“He was an arsehole, let’s face it,” says Gillan, more bluntly. But the singer insists his own departure was prompted by problems with the band’s management, rather than his ongoing contretemps with the recalcitrant guitarist.

“The things that were going on behind the scenes were to me just utterly shocking,” he says. “I’d never worked with people that told me they were gonna throw me back in the gutter where they’d found me, and threatened violence. It was not nice. It was not pleasant at all. And of course that clouds the musical side of things.”

Gillan’s frame of mind wasn’t helped by the band’s relentless workload. Five days after the Japanese tour, Purple were back on the road in the US, followed by another British tour. Finally, at the end of October, they fitted in a fortnight in a village outside Frankfurt to finish what would become the MK II line-up’s last album of the decade, Who Do We Think We Are.

“Relations between Blackmore and Gillan had reached a point where they weren’t actually talking to each other,” Glover remembers.

The strains showed in the album. The odd arresting moment, such as opening track Woman From Tokyo, aside, it was a poor effort and, coming after Made In Japan, an anticlimax. Despite having resigned, Gillan had agreed to see out the next six months’ worth of commitments, though it meant that he and Blackmore had their own separate road managers. The situation didn’t mean their mutual antipathy was easing. Colin Hart recalls an occasion after a show in Cleveland when Gillan was sitting in the dressing room, talking amiably with friends:

“Ritchie walked in and picked up a plate of hot spaghetti and planted right in Gillan’s face – in front of everyone. I mean, talk about everything stopping in freeze-frame. Everybody waited for this gigantic explosion that was about to happen. And it never did. Gillan just sat there calmly, wiped two eyeholes in the spaghetti then carried on talking like nothing had happened. And that infuriated the shit out of Ritchie, who then stormed out of the room and started plotting some other revenge.”

Following this particular spaghetti incident, Gillan distanced himself from his bandmates. He would take separate flights and often stay at different hotels, avoiding seeing anyone until he got to the show.

“He’d roll up in a car 10 minutes before stage times, go on, do the show, and he was gone before he saw anybody,” says Hart.

As if to express his impending freedom, the singer had cut his shoulder-length hair and grown a beard. He was accompanied on the tour by his girlfriend, Zoe. According to Colin Hart, the couple had become Deep Purple’s own John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

“He was inseparable from her at the time,” says Hart. “She’d go everywhere with him. And I know she wasn’t the most favourite person among the rest of the band. She wouldn’t say a word, which was very spooky. She’d just sit there and stare. Wouldn’t even smile, you know?”

Today Gillan shrugs it off. “Success amplified everything, and I must have been just as much of an arsehole as Ritchie, if not more, particularly with the personal situation and girlfriends and all that. It was difficult for everyone.”

By then, however, it wasn’t just Gillan who was on his way out. For a while, Glover was convinced that Blackmore and Paice were going too.

“Ritchie had been toying with leaving and forming a band with Phil Lynott and Paicey,” he recalls. They were going to be a trio.”

Glover insists that Tony Edwards and John Coletta, the band’s managers, took him and Jon Lord out for dinner and asked if there was any way they could get Paice back, so they could get a new singer and a new guitarist and carry on.

“As far as I knew, that was the plan,” says Glover. “Jon and I had talked to Paicey and he said: ‘I’ll think about it.’ That was the last I heard, until I had this feeling…”

As chance would have it, Gillan’s final show with Purple was back in Osaka, in June 1973, at the same venue where most of Made In Japan had been recorded 10 months before. By then it had also been decided – unilaterally by Blackmore – that Roger Glover would also be making his last appearance with the band.

“I think Ritchie wanted a bass player who was a bit more dangerous, a bit more virtuoso,” says Glover. “Maybe someone who could sing as well. Ritchie wanted a change. He’s like that. He wants fresh impetus, he wants stimulus. And I think he saw the opportunity arising with Gillan going, coupled with the fact that Purple were huge, that he could stay with the band. So that’s why I was edged out.”

On the night of his final gig, Glover passed Blackmore on the stairs. The pair hadn’t spoken for days. The guitarist looked at his soon-to-be-ex-bandmate and said: “It’s nothing personal, just business.”

Today Glover admits that he was devastated. Colin Hart recalls seeing the him on the floor of the dressing room after the Osaka show, absolutely inconsolable.

“Jon and Ian were upset,” says Hart. “They tried to comfort Roger as best they could.”

“It was tough,” says Glover. “I didn’t take it very well. All I’d done was worked my hardest for the band, and seen my life change and go on this golden chariot across the world, and all of a sudden the carpet’s ripped out from under you. It was a long drop.”

Gillan, meanwhile, had a completely different reaction. He walked on stage in a white dinner jacket, doing most of the show with his hands in his pockets and a broad smile on his face.

“I felt no sadness at all,” he says. “It was like casting off a burden. These things are so difficult to explain, but unhappiness is a powerful thing. Talk about why was I happy that night – probably because I just wasn’t unhappy any more.”

“He was very nonchalant, cool, to the point of being eerie,” Colin Hart recalls. “He just walked on stage, did his best, then casually walked off and went out and had dinner. Roger was mortified. They did a brilliant show, but at the end it was very sad to see Roger sitting on the floor in the dressing room just totally, totally devastated that it was over.”

Hart claims that more than one party tried to talk Gillan out of his decision, including management:

“I know Roger poured his heart out to Ian to try to get him not to go. Ritchie probably just licked his fingers and went [adopts Mr Burns voice]: ‘Splendid! Let’s move on!’”

Ian Paice and Jon Lord harboured hopes of resolving the situation right up until the long flight home to London the next day. But Gillan and Zoe had already left on a separate flight, and Glover was still a hopeless wreck. The Mk II line-up was finished.

“It wasn’t until days later that it began to sink in that Ian and Roger really weren’t coming back,” says Paice, who celebrated his 25th birthday on the day of the Osaka gig. He admits that a degree of self-preservation had come into play. Which is understandable, given that he, Lord and Blackmore had grown the band from its roots and were its musical core.

“I was the youngest guy in the group, and I wasn’t about to walk away from it because things hadn’t worked out for two of the other guys,” the drummer says now. “I felt really bad for Roger. I sometimes wonder what would have happened if we’d kept him. Would Ritchie have stayed with the band longer than he did? [Blackmore left just two years later after becoming disaffected by the funkier direction partly sparked by Glover’s replacement, Glenn Hughes.] We should probably have had six months off and then got back together, but groups didn’t take six months off then. Nobody knew a group would last more than a couple of years. So you did what you had to do.”

Of course, the story of the Mk II line-up of Deep Purple was far from over. But it would never again attain the creative heights of Made In Japan. Before it, most live albums really were regarded as ‘cheap and trashy’ as a Japanese-made imitation watch. After it, the double live album became a big gun in the arsenal of any band who wished to be considered part of rock’s upper echelons. For some, such as Lynyrd Skynyrd [One More From The Road] and Thin Lizzy [Live And Dangerous], double live albums became their biggest-selling records and then represented the apex of their career. Further down the line, for others, such as Iron Maiden [Live After Death] and Pink Floyd [Pulse], they became a surrogate ‘greatest hits’ collection.

Some artists operated on a more self-consciously exalted level by releasing live doubles that flagged-up the artistic arc of their career while radically reworking some of their most classic material: Bob Dylan & The Band’s Before The Flood, in ’74, or Joni Mitchell’s Miles Of Aisles from the same year. Today Made In Japan stands as the big daddy of the double live album, and the pinnacle of Deep Purple’s career. Over 40 years after its release, Roger Glover admits that he still listens to it every once in a while.

“It still amazes me, all the little things that I’d forgotten,” he says. “All those moments on stage where you don’t know what’s happening. They relied on a look or a musical signal or a gesture, or just luck. We used to call it horse’s eyes. You know, when you look at each other, mentally counting off, waiting to come back in…”

- Roger Glover's track-by-track guide to Deep Purple's InFinite

- Deep Purple Albums Ranked From Worst To Best

- Read Classic Rock, Metal Hammer & Prog for free with TeamRock+

- Ian Gillan: The Day I Left Deep Purple

WHATEVER HAPPENED TO BABY FACE?

Revealed: the Thin Lizzy-Deep Purple supergroup that nearly was.

It was one of the great ‘what if’s of the deep Purple story: the union between Ritchie Blackmore, Ian Paice and Thin Lizzy frontman Phil Lynott under the name Baby Face.

In late 1972, Blackmore and Paice approached Lynott with the idea of forming a band that would let them flex their muscles outside their increasingly strained confines of Deep Purple. Lynott had come to the guitarist‘s attention after he heard Lizzy’s self-titled 1971 debut album.

“Ritchie used to love his singing,” says Purple tour manager Colin Hart. “Kind of like a young Rod Stewart or Paul Rodgers.”

With Thin Lizzy yet to make a big breakthrough, Lynott took Blackmore and Paice up on their offer. Settling on the name Baby Face, the guitarist instructed Hart to arrange an impromptu session at De Lane Lea studio, where Made In Japan would be mixed less than a year later.

“They did a couple of covers,” says Hart, who was in the studio with them. “It was only a short session, two or three songs, then it was out with the equipment and off home.

I don’t think they did anything original. It did sound great together, the three of them.”

“It was meant to be a free-flowing kind of thing,” recalls Paice, who says the reason nothing came of Baby Face was purely musical. “It never got off the ground mainly because Phil wasn’t really a good enough bassist yet. He had the voice, but learning to play bass well takes time. And for a thing like that to work, all three players need to be at a certain level. Phil just wasn’t there yet.”

The connection between the two bands didn’t end with the aborted collaboration. The name Baby Face would end up being used as a title on Lizzy’s next album, and the Irish band would record a deep Purple tribute album in 1972 under the name Funky Junction (though vocals would be provided by Benny White of Irish group Elmer Fudd) But, for a brief moment, the prospect of an early-70s supergroup was tantalisingly close.

“Phil was bowled over by Blackmore,” Lizzy drummer Brian downey later said. “That was the first time I’d ever seen him hesitate about anything.”

“I THOUGHT, ‘THAT’S NOT JAPAN. IT’S BRIXTON!’”

Def Leppard’s Phil Collen on how he ended up on the back of Made In Japan.

I remember getting Made In Japan and looking at that shot on the back and realising it was me – the blond chap standing in the audience right in front of Ritchie Blackmore.

I thought: ‘That’s not Japan. That’s Brixton!’ It was at the Brixton Sundown, now known as the Academy. It was the first show I’d ever been to – I was 14, and I got right up against the stage. I didn’t play guitar yet, and it was that show, standing in front of where Blackmore was standing on the stage, flashing his Strat, playing all this stuff that no one else did in those days, that made me pick up a guitar and learn, literally, the next day.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock issue 176.