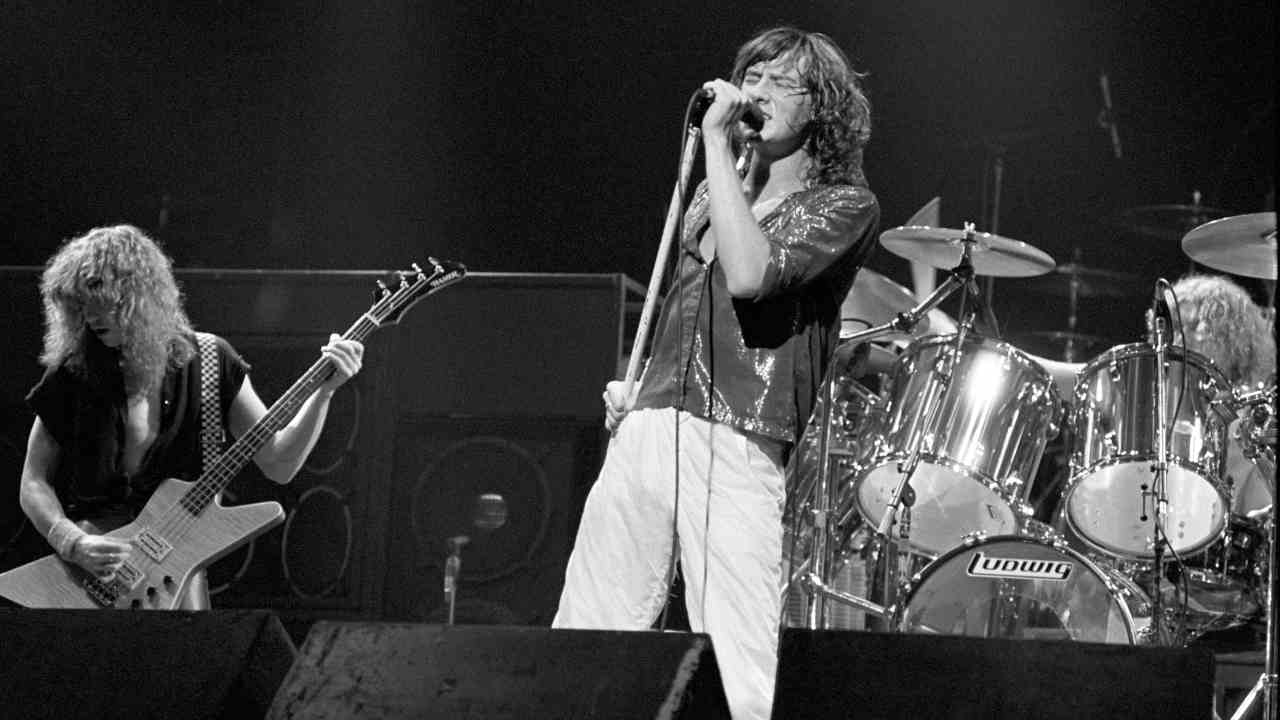

Sunday, August 24, 1980: the final night of Reading festival. Second-on-the-bill to headliners Whitesnake, this should be the crowning glory of what has been a momentous year for Def Leppard. Instead disaster awaits them. No longer the darlings of the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal, thanks to poisonous reviews of their debut album On Through The Night, and being lambasted for sounding ‘too American’ – a hanging offence in 1980 – Leppard have suddenly taken on the mantle of sell-outs, even traitors. At least to a particularly vociferous section of hard-core metal fans, that is.

Party Seven (seven-pint) beer kegs – some not empty – fly onto the stage as the band run about on it, doing their best to ignore them. Eggs are thrown at them. A huge grass sod flies up and hits guitarist Pete Willis square in the bollocks.

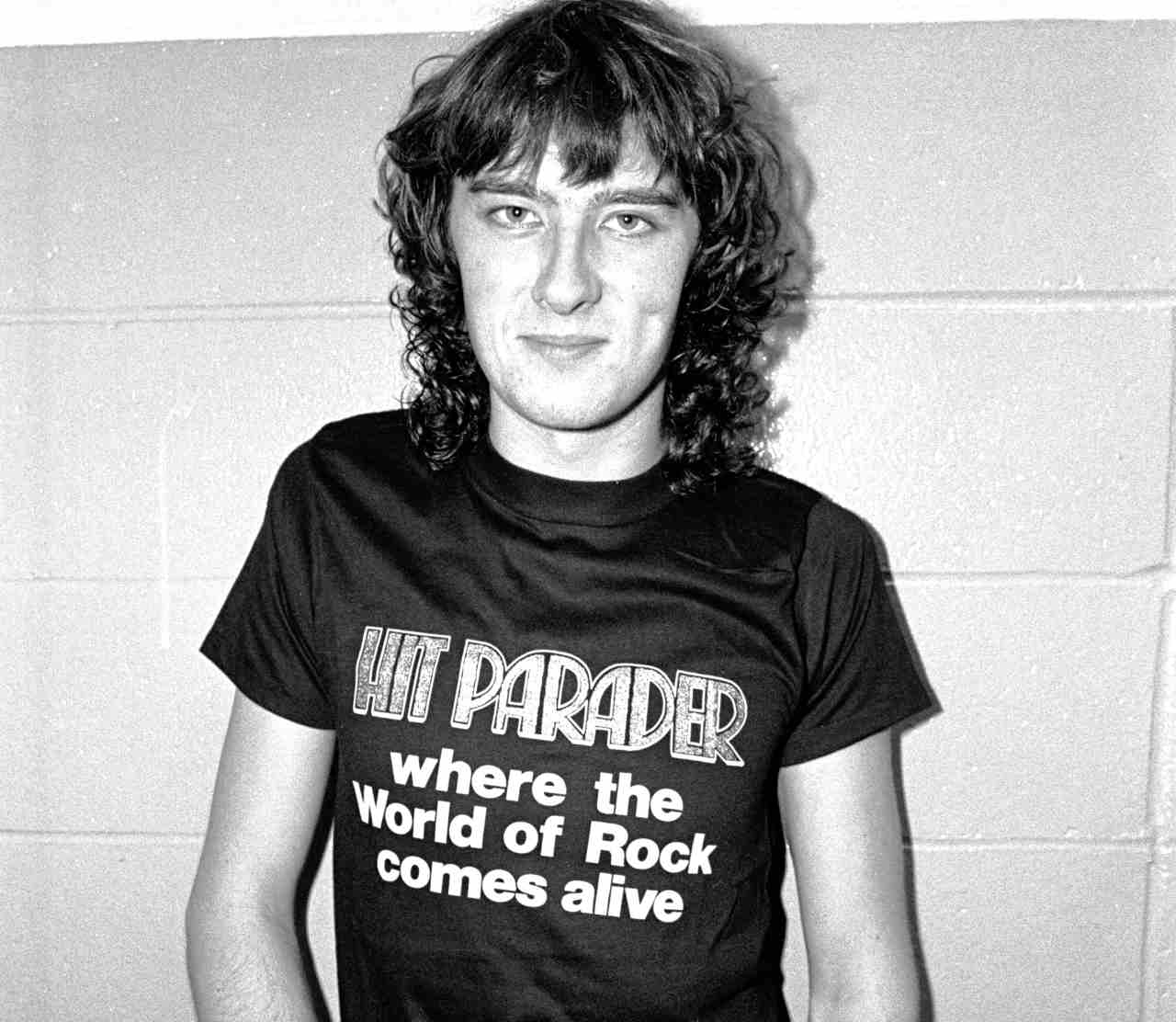

“Some of it was self-inflicted,” Leppard singer Joe Elliott admits today. “I went on stage in a pair of bright-red trousers, and a white shirt covered in hearts. That was me going: ‘I’m not fucking wearing a leather jacket and jeans like every other bastard band in this movement that we don’t think we’re in anyway.’”

Be that as it may, it hadn’t stopped Elliott and Leppard lapping up the attention that their self-financed, self-titled EP was given in music weekly Sounds – birthplace of the NWOBHM – when it was released a year before. After championing them, along with Iron Maiden, as the cream of the NWOBHM crop, Sounds had done a 360-degree turn on Leppard, accusing them of being more interested in pursuing the American dollar than in making it big in their own backyard. That perception was only reinforced by the release of the album’s apparent mission-statement, Hello America.

“I swear to God we really weren’t that intelligent,” bassist Rick Savage says with a laugh. “It was the lyrics of a kid fantasising… I can see how people read into it, but it was way more innocent than that, way more naive.”

Not that the people throwing crap at them on stage at the Reading festival in 1980 saw things that way. Regarded now as the lowest point of their career, Reading may have shown the young Leppards to be naive; innocent they most assuredly were not.

Formed in Sheffield in 1977, Def Leppard had always been a band with big plans. Hence the later ditching of the small-town management team that got them their major record deal with Phonogram, in 1979, and replacing them with Leber-Krebs, the same New York-based management operation behind the then-recent Stateside success of AC/DC, and who went on to form Q-Prime.

No wonder they so soon inspired the sobriquet ‘flash bastards’. Def Leppard had set out to be the flashiest bastards around, and by 1980 they were well on the way to achieving it. Not least on the streets of Margaret Thatcher’s Britain, which were then crumbling beneath the twin economic perils of rampant inflation and sharply rising national unemployment figures.

“We were teenagers,” says Savage, “and we had this belief that anything was possible. When that way of thinking is moulded into the group at that very early stage, it never really leaves you.”

It would be several more years before a new generation of British fans would come along that had grown up with the same aspirations. None of which seemed probable back in the cold, stark winter of 1980, as Leppard set about writing the follow-up to their provocative debut. The result was an even more outgoing and determinedly America-friendly album called High ’N’ Dry.

“The trouble was, we were moving so fast, we couldn’t see that we were doing anything wrong,” says Elliott. Indeed, it had been the band’s energy and colour that had first attracted people to Def Leppard. At the time I first saw them play live, opening for Sammy Hagar at London’s Hammersmith Odeon, in September 1979, I was working as a PR with both old- and new-wave rock and metal bands such as Thin Lizzy and Black Sabbath, the Damned and Motörhead. Unburdened by the narrow parameters of the self-styled NWOBHM scene, as then portrayed each week in Sounds, I saw only a British band with a very definite international future.

When their greater ambitions led them to fall foul of the NWOBHM police, they were puzzled. As Elliott points out, by the time Leppard set off for their first US tour, in the late spring of 1980, “there was nowhere else left [in Britain] to play”. They had played 47 club shows already that year, “from Aberdeen to Bournemouth”. When On Through The Night came out in March ’80 and went Top 20, they moved up to theatres, proudly selling out their biggest local venue, Sheffield City Hall. “The next logical thing to do was what every great British band has ever done – go to the States and see if we can crack it.”

Iron Maiden had actually arrived in America a month before. “I didn’t see them getting any flak, nor should they have. So why the hell did we?”

The answer, of course, lay beyond the music. Leppard had never conformed to the blokey stereotype of the NWOBHM. Young, exciting and defiant, with their musical and sartorial influences as much about Queen and David Bowie as about Led Zeppelin and Judas Priest, there was never anything remotely ’umble about their ’eaviness. These attributes set Leppard apart from the inherently parochial mien of any so-called movement with the word ‘British’ in its title.

It wasn’t just in the pages of the music press they were now being attacked, either. It was also on the streets of Sheffield, where they all still lived with their mums and dads. Elliott recalls going out with guitarist Steve Clark and having to fight their way out of Sheffield bars they had once been regulars in. Another time “a couple of kids gobbed on us. Me and Steve just looked at each other and went, ‘Sod this,’ and we rented a car and drove to London, and slept on the Tottenham Court Road for two days in the back of the car.”

By the time they’d made their fateful Reading appearance, Elliott had already moved permanently to London. His parents were on holiday at the time. He left them a note.

“It was a very emotional moment. But I wasn’t a kid any more. I took my belongings – all 75 albums and a couple of pairs of socks – and legged it down to this house in Isleworth. I had 10A in the basement. [Gillan guitarist] Bernie Tormé had 10B. I had a crappy old Morris Marina that my dad had helped me buy for £595 – those were my rock’n’roll wheels.”

It wasn’t long before the others began to follow. “Joe was always the leader,” says Savage, “the guy who took the responsibility for the whole entity of Def Leppard, not just the music.”

Closest to Elliott was Rick Savage, the stereotypically ‘quiet one’ on bass, who took on the “responsibility to make sure there wasn’t too much of a distance created between the other factions in the band”. Namely the band’s two wildfire guitarists: co-founder Pete Willis, and Steve Clark. The former was a super-solid rhythm player whose essentially shy character – happy to hide on stage behind curtains of dark hair – and diminutive stature belied an equally short temper, especially when he’d been drinking, something that was already growing into a crisis by 1980. The latter was the spontaneous soloist of the group, whose ability to improvise sensational breaks and flurries also disguised a greater insecurity away from the stage, especially in the demanding, do-it-again environment of the recording studio, and whose own drinking habits would also later spiral dangerously out of control.

The loner of the group was also the youngest: drummer Rick Allen, whose brilliance had landed him the gig at the tender age of 15, but whose off-stage proclivities threatened to have him thrown out of the band before it had barely got going. As he puts it now: “I was very young then and – what do they say? – experimenting.”

Or, as Savage says: “Rick was just happy trying to get away from reality by taking loads of silly drugs and hallucinating. But we were a proper band, with a mutual respect for each other’s position, a gang.”

By the time Leppard began work on High ’N’ Dry, the gang’s shared sense of injustice was also growing.

“Too big for our boots?” Elliott asks rhetorically, the edge still in his voice 30 years later. “On stage, absolutely. We were a bunch of kids destined for factory life. We knew the opportunities we were being given. We were not going to screw this up. Off stage, though, there’s nothing more humbling than trying to make a record and signing on, or poncing off your girlfriend who’s signing on.”

The most money they had seen so far was the £30-a-week stipend they enjoyed on tour. Everything was riding on the success of their next album. Enter their knight in headmaster’s clothing: legendarily reclusive producer Robert John Lange – ‘Mutt’ to his few friends.

Born in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) in 1948, Lange was the son of a South African mining engineer father and a mother from a well-to-do German family. A multi-instrumentalist in his own right but whose band Hocus had failed to make the charts, Lange had subsequently forged a career as an in-demand producer of hits for late-70s punk-pop outfits such as the Boomtown Rats (Rat Trap and I Don’t Like Mondays both owed their success to Mutt’s cathedral-like production) and several others. More recently he had masterminded multi-platinum hits for AC/DC (Highway To Hell, Back In Black) and Foreigner, whose album 4 was about to become their biggest-selling ever.

Leppard’s new American manager, Peter Mensch, had originally wanted Mutt for their first album but he’d been unavailable. Now they would have to wait again while he finished working on Foreigner’s 4, filling in time by supporting the Scorpions in Europe. Elliott was working on a building site when, in January 1981, he was told they’d have to wait another month for Mutt. “I went to my record collection, took Double Vision out and snapped it in half.”

When Leppard did finally start recording with the producer, in March 1981, it was the start of what would become the most fraught yet ultimately rewarding relationship of the band’s career. With his chiselled, clean-shaven looks and light-coloured, curly hair, Lange could have been Elliott or Sav’s elder brother. In fact he would become the father figure of the group as, over the next seven years, he helped to transform Leppard from NWOBHM rejects into globally acclaimed rock superstars. Mutt held the keys to all this and more, as he proved time and time again. All you had to do was follow his rules – to the letter.

“The first day, he was giving us directions,” Elliott recalls, “and Pete was eating this apple. Mutt just went off at him, really ripped into him, cos Pete wasn’t paying attention. It was like being at school; we were all staring at the floor going, ‘Oh, God…’”

That had been at the well-appointed John Henry’s Rehearsal Studios in north London. With the steady-as-she-goes commercial breakthrough of On Through The Night, and now the recruitment of a producer of Lange’s stature, the budget for Leppard’s second album had increased exponentially – as had expectations for its success. Suddenly the pressure was on.

When, in March 1981, recording finally commenced, at Battery Studios in Willesden Green, north-west London, Mutt was already “like the sixth member,” says Allen. “High ’N’ Dry was starting with a blank canvas, all we had was just riffs and beginnings of ideas. [Mutt] proceeded to tear the fucking thing apart and piece it back together, bit by bit.”

Despite its out-of-the-way location, Lange favoured Battery for its excellent 1976 Cadac analogue desk – an antique now, state-of-the-art then. Originally known in the 70s as Morgan, Battery had hosted a wealth of UK rock talent, including Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and Paul McCartney. A decade later it was the crucible in which the Stone Roses forged their game-changing debut, and where Lange returned to record albums for Shania Twain and Bryan Adams. When Leppard first arrived, Iron Maiden had just vacated it, having been working with their own stellar producer, Martin Birch, on their second album, Killers.

Leppard would turn up each day at Studio One – the larger of Battery’s two main studios – to find Lange already hard at work. “He was always first in and last out,” says Elliott. “Later on, he’d just sleep in the studio – work until 4am then pass out on the couch. He worked his butt off, and he instilled that in us.”

One of the new songs they’d been played at Reading was When The Rain Falls. “Mutt saw it as potentially our Highway To Hell,” says Elliott. “But the words were all wishy-washy, introspective bollocks: me stuck in my parents’ house ’cause it’s raining. Mutt said: ‘We’ve gotta go more global.’ So we thought more of Queen, We Will Rock You, and renamed it Let It Go.”

During the vocal recording of A Certain Heartache – which, at Mutt’s instigation, had been renamed Bringin’ On The Heartbreak – an exasperated Elliott went next door to Battery’s Studio Two, where Whitesnake were recording Saints & Sinners, seeking advice from vocalist David Coverdale.

“I watched David lay down a vocal with one take. Next thing he gets out the brandy, and I’m leaning on the piano, listening to him tell all these Deep Purple stories. I’m getting bollocks-drunk, and David’s going [deep-voiced and Yorkshire accent]: ‘Don’t you worry, brother Joseph, it’s gonna be all right!’”

Elliott’s only other memory of that day is “puking all over the pavement”. But the next day, however, “it started to click. I’d got the verses done, just piecing them all together, and [Peter] Mensch looked at Mutt and went: ‘Is that my fucking singer?’ He’d never heard me sing like that – neither had I. I thought, if this is what working with [Mutt] can do for me, then I’ll put up with all the pain.”

“It was the first time any of us really experienced what hard work is about,” says Allen, who’d begun “to doubt my ability to play drums. I was competing with [AC/DC drummer] Phil Rudd. People ask who your influences are as a drummer. Well, really, it’s Mutt Lange.”

When the album was finished three months later – “lightning-fast compared to the months and years we spent on the next two albums with Mutt,” says Elliott – they had created what Savage calls “the launch pad for the rest of our career”.

Not that anyone could have foreseen that when High ’N’ Dry was released in July 1981. For despite a recanting five-star review in Sounds, the album singularly failed to catch fire in the UK, barely scraping the Top 30. “Everybody loved it,” recalls Elliott, “but nobody bought it. We toured the same places we did a year earlier, this time to balconies closed off. Horrible, cold, wintery, crap, half-sold-out venues.”

More worryingly, it was a similar story in the US, where sales of High ’N’ Dry stalled at around the quarter-million mark – less than half what the record company suits had been projecting, and only slightly more than On Through The Night .

There were, however, other consolations. “The American girls were lovely,” says Joe. “I couldn’t get a girl to look at me in England, even on stage, for God’s sake! [In America] we were shocked at some of the stuff we saw. The first time I saw [well-known groupie] Sweet Connie, in Little Rock, I ran a mile. I didn’t go where other people have been; it was either the girl behind the counter at the hotel or the stewardess on the plane.”

Party nights on the road in the US also presented other temptations. “I kind of pushed that envelope as far as I could,” Allen admits. Already chastised for spending too much time with the roadies, smoking dope, Allen now began to experiment with cocaine. “I remember lying in bed in Reno the first time I ever experienced an earthquake. But I didn’t realise it was an earthquake. I thought it was my friggin’ heart.”

There was one major casualty from that tour, though: Pete Willis. “Pete was great,” says Allen, “but every time he had a drink it would completely change his personality. He’d go from ‘we, we, we’, to ‘my, me, mine’.”

Unfortunately, Willis’s drinking was now an everyday thing. “At first it’s funny,” says Elliott, recalling how they’d had to “pour Pete off the plane” the first time they flew to Los Angeles. “They were all jolly japes, but you’d get angry with him if he had a bad gig the next night. That’s when you start going nuts. We had fisticuffs about it, and tears. He didn’t let anybody down in the studio on High ’N’ Dry, but on the tour that followed he was a bigger problem than he’d ever been.”

So much so that Elliott was now making clandestine calls from America to former Girl guitarist Phil Collen. “I’d say: ‘Can you learn 18 songs in three days?’ Then in the sober light of day I’d phone and say: ‘Look, he’s apologised, so it’s not going to happen. But bear this in mind – in case.’ Pete must have been given a hundred chances.”

“Pete was finding it difficult to either believe what was happening or understand it, and was uncomfortable with it,” says Savage.

Sacked during the formative stages of Pyromania, after Mutt lost patience and refused to work with him further until he cleaned up his act, Willis’s departure may have been, as Elliott insists, “when we woke up to the real us”. But it was a devastating blow to their former school pal. He came back, in 1985, to record an EP with the Jonathan King-led ‘metal supergroup’ Gogmagog (also featuring ex-Maiden members Paul Di’Anno and Clive Burr) but it was a short-lived, disenchanting affair. Other brief forays followed over the years – notably Roadhouse, whose 1991 self-titled album sneaked into the lower reaches of the UK Top 30 – but in 2003 he announced his retirement from the music business.

Whatever the rights and wrongs, Willis’s replacement by Collen also marked the moment when Leppard ceased to be a gang and became something else entirely: a veritable hit machine. In fact High ‘N’ Dry was to live a charmed after-life when, eight months after its anti-climactic release, the newly launched MTV started rotating the Bringin’ On The Heartbreak video like a spit.

Elliott: “We were getting telexes telling us the album had sold 10,000 copies that week, then 30,000 copies a month. By the time Pyromania came out, High ’N’ Dry had done 800,000 in America. Now we’ve got an audience that’s primed and ready to go, at least in the States.”

In Britain it would take the total reinvention with their 1987 album Hysteria to reopen the commercial floodgates. By this time Lange was taking two years to record a Leppard album, and all the curvaceous twists and jagged turns of High ’N’ Dry had been erased in favour of a more svelte sonic plateau.

For many Leppard fans High ’N’ Dry remains a true rock classic and, as Savage says, the springboard for all that followed it. “Because it wasn’t as successful as we would have liked, Mutt was hell-bent on making sure everything else we did was a hit. And that’s why we started taking so long making records. When High ’N’ Dry wasn’t as successful as Mutt thought it should have been, then it became personal.”

Originally published in Classic Rock 159 (May 2011)