It was in the summer of 2005 that Phil Collen said what every member of Def Leppard was thinking: enough is enough.

“Fuck it!” the guitarist snapped. “We’re better than this.”

The band were in America’s Deep South, performing at a state fair in a dusty field on the banks of the Mississippi River. And, as they knew only too well, the state fair circuit was where rock stars go to die.

As singer Joe Elliott explains it now: “In one sense, state fairs are like every other gig – big stage, big audience. But there’s a stigma that comes with it. It’s the difference between an eighties artist like Madonna doing six nights at Wembley and an eighties package tour featuring Marc Almond and the Thompson Twins at Butlin’s. And at a state fair you’re just one of the attractions, along with a big wheel and firework display, and a juggling pig or whatever. It’s not exactly Madison Square Garden.”

When Collen recalls the scene from that night in 2005, he can laugh now at the tragicomic absurdity of it all.

“It was like a carnival,” he says, “if you can imagine doing a gig at a carnival. They put fucking deck chairs out! It was full-on Spinal Tap. Like: ‘Are we going on before the puppet show?’” I was so pissed off. I just thought: ‘I don’t want to do this any more.’”

At the time, the humiliation of their predicament burned deep. For a band that had sold millions of records during the golden days of the 80s, it was a bitter pill to swallow. Def Leppard had dug deep before. Sheer force of will had seen them through the darkest times: drummer Rick Allen losing his left arm after a car crash on New Year’s Eve 1984; guitarist Steve Clark succumbing to alcoholism and dying at the age of 30 in 1991.

The band had also weathered the storm of the alternative rock revolution of the early 90s, which had destroyed the careers of lesser 80s stars. But in 2005 they found they were fighting a losing battle. The thought of leaving the band never entered Phil Collen’s mind.

“What I thought,” he says, “is that we’re in a rut and we need to change. And everybody backed me up on it.”

It was a turning point for Def Leppard. The change that Phil Collen demanded – and that every member of the band agreed upon – would lead, in time, to a late-career renaissance. In 2022 their stock is as high as it’s been in decades. May saw the release of Diamond Star Halos, the most anticipated new Def Leppard album since Adrenalize back in 1992. And now they're part of the biggest US rock event of the summer, The Stadium Tour, co-headlining with another superstar act from their original purple patch in the 80s, Mötley Crüe. Def Leppard have come a long way since Phil Collen lost his shit at that state fair.

“If you stick around long enough,” Joe Elliott says, “you will go through a drift period – the wilderness years, as people like to call it. But if you hang in there, you might just pop out the other side…”

When the five members of Def Leppard talk to Classic Rock – about the new album and all that has led up to it – they are spread far and wide. Joe Elliott is at the home in County Dublin that he shares with wife Kristine and their two young children.

Phil Collen is in Los Angeles, his house now filled with the noise of his three-year-old son, an echo of times gone by for a man whose eldest daughter is in her thirties. Bassist Rick Savage – known to all simply as ‘Sav’ – is in Sheffield, the band’s home town, where he has remained except for a 15-year period when he lived in County Wicklow, 10 minutes from where Joe lives now. He has a grandchild, and another on the way; “another invasion,” as he jokingly puts it.

Guitarist Vivian Campbell is in the Irish town of Donegal, in the house where he spent his summers growing up, now owned by his brother John after their parents passed away some 12 years ago. Vivian and his wife Caitlin, who married in 2014, recently moved to New Hampshire, on America’s eastern seaboard. Rick Allen is in London attending to band business, taking a break from family life in California, where he lives near the town of Monterey with his wife and their 11-year-old daughter.

For the recording of Diamond Star Halos, the original plan was essentially the same as it’s been since 1999: to work at Elliott’s home studio, named – with a nod to Frank Zappa – Joe’s Garage. But the pandemic nixed that plan, the first lockdown beginning in the week when the band were due to get together in Dublin. Instead they pushed ahead by working remotely from their homes, recording song ideas and individual parts on laptops. This material was shared via Dropbox and then collated into finished tracks by the band’s long-serving producer Ronan McHugh, working out of a studio in his back garden.

As Phil says, this separation actually worked to their advantage: “When you’re in a studio, waiting for someone else to finish a part, you can lose an inspirational flow. It kills it, sterilises it. But you don’t have that problem when you’re working on your own.” He turns his laptop around to show Classic Rock the minimalist set-up he has in his living room: a desk piled high with recording gear, a rack of guitars close by. “I recorded everything here,” he says. “I used Logic, which is easier than using a phone.”

According to Joe, even the fact that various members were in different time zones proved beneficial. “It was so exciting to wake up in Dublin and see a message from Phil with a new idea,” he says. “This was a whole new way of working for us – and I don’t think we’ll ever do an album the traditional way again. This way, there was no pressure. And the record doesn’t sound disjointed. It sounds like a band all on the same page, which is what we are.”

For this album, the bulk of the songwriting was done by Joe and Phil. Two ballads, Goodbye For Good This Time and Angels (Can’t Help You Now), were written by Joe on piano; it’s something he has grown into with the Down ‘N’ Outz, the extracurricular project he formed in tribute to his heroes Ian Hunter and Mott The Hoople.

Phil wrote a couple of songs alone, and also worked with two American songwriters who are friends of his. Two songs were written with Sam Hollander, whose previous clients include Katy Perry and Panic! At The Disco. Fire It Up was based on Queen’s We Will Rock You and Joan Jett’s version of I Love Rock ‘N’ Roll.

“I wanted a rock anthem,” Phil says. “We’ve had them before, like Pour Some Sugar On Me and Rock Of Ages. But it’s hard to write one that doesn’t sound naff and contrived.”

Kick, the album’s lead single, is a throwback to the glory days of glam rock. “I thought it would be great to do something that was very seventies, very Gary Glitter – if you can say that these days,” he adds with a grimace.

Surprisingly, Phil hadn’t written these songs with Def Leppard in mind, but when he played them to Joe the reply was emphatic: “Don’t give them away!” Another of Phil’s songs, This Guitar, was co-written with CJ Vanston, who has worked with various big hitters from Toto to Tony Bennett. It has a country flavour – “like the Eagles,” Joe stresses, “not Dolly Parton” – and is one of two songs on the album performed as a duet with Alison Krauss.

“We’ve had This Guitar knocking around for maybe seventeen years,” Joe explains. “So I said: ‘For God’s sake, can we try it this time?’ It’s such a great song, so I had to deliver. It’s one of the best vocals I’ve ever done, and I did it on my laptop with a two-hundred-dollar mic.”

Sav wrote the songs that bookend the album. Two of the band’s best songs from the past 25 years were his: the power ballad Goodbye and the Queen homage Love. For this album he wrote two brilliant, but very different, numbers.

“I did feel we were lacking that straight-ahead, riff-oriented song,” he says of Take What You Want, which has a similar feel and structure to Let It Go, the opener on 1981’s High ‘N’ Dry. “A really balls-out fucking rock song”, as Vivian calls it, but with a melodic breakdown reminiscent of The Beatles’ psychedelic period. The album’s closing track, From Here To Eternity, is an epic ballad with lyrics inspired by film noir.

“I was thinking Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall,” Sav says. “It’s a typical 1940s gangster scenario: a guy sees his lover shot dead, so he shoots the guy who killed her, and now he’s going to the electric chair. So, a love triangle where everyone dies. Joe calls it our murder ballad.”

Rick Allen did not contribute to the writing, and has done so only rarely in the past. More surprising is the absence of any songs written by Vivian Campbell, given that he wrote key songs previously, such as Work It Out from the Slang album. With a shrug, he explains: “I just wasn’t ready this time. That’s the bottom line. I thought we were going on tour, and then it was: ‘We’re making a record!’ I was in full panic mode. I do feel bad for not pulling my weight. But it wasn’t like we were short of songs.”

As Joe puts it: “Vivian was happy to do the Ronnie Wood thing on this record. But his contribution to this record is immense from a performance point of view. His Hendrix-like solo in This Guitar is superb.” He says the same of Phil’s solo in Open Your Eyes, modelled on Mick Ronson’s mind-blowing outro to David Bowie’s Moonage Daydream. “That,” Joe says, “is the best thing Phil’s ever played.”

The album’s title is another connection to 70s glam rock – a phrase lifted from the T.Rex classic Get It On. As Joe says: “Whenever people take a dig at our lyrics, we’ve always said: ‘We’re more Marc Bolan than Bob Dylan, more ‘hubcap diamond star halo’ than ‘the answer is blowin’ in the wind’! So when Phil suggested the title, we all went: ‘Fuck, yes!’ Glam is in our DNA.

"We’re all big fans of Zeppelin and the Stones, but really, in a musical sense, we were born on Top Of The Pops – Bowie, Bolan, Slade, Sweet. With this album we’ve gone back beyond the eighties to the seventies and all the music that inspired us as kids. Yet it still sounds like 2022 – even though we did it in 2020.”

What all of this adds up to is arguably the best Def Leppard album since Adrenalize. “What we’ve delivered is the ultimate album for who we are now,” Joe says. What is also evident is the level of expectation ahead of its release, and this is not lost on the singer. “We haven’t had a buzz like this for ages,” he says. “And the reason we’re so confident about this record is that the people closest to the band are confident in us.”

Rebirth. It’s a word that Rick Allen used before when he was talking about Def Leppard’s biggest-selling album, Hysteria, and what it represented to him on a personal level. It was during the making of that album that his life was forever changed. What it took for him to maintain his position as the band’s drummer was an extraordinary degree of self-belief. Now, when Rick talks about rebirth, it’s about where the band are in 2022, compared to 17 years ago.

“At a certain point we were about as hip as fucking haemorrhoids!” he laughs. “But it’s fantastic now.” As Sav puts it: “You need a little luck, a little belief, and a little arrogance to stick around knowing that, eventually, the wheel will turn back in your favour.”

And, in 2005, it was one bold decision that set the wheel in motion. American manager Peter Mensch had begun working with Def Leppard in 1979, and his partnership with fellow American Cliff Burnstein in their company Q-Prime was instrumental in turning a band with raw talent into one of the biggest acts in the world. Their experience also helped guide the band through the traumas of Rick’s accident and Steve Clark’s death. As Phil acknowledges: “Peter and Cliff were great. They did all the groundwork and broke us in the eighties.”

But in 2005 it was decided that the band’s relationship with Q-Prime had run its course. The break was made, freeing the band to sign with HK Management, led by Howard Kaufman, whose roster featured heavyweights such as Aerosmith and Fleetwood Mac.

“No band can work well without a great team,” Joe says. “Look at Iron Maiden and Rod Smallwood, who’s been with them since day one.”

Joe expresses his gratitude for what Mensch and Burnstein did for the band – “If I saw those guys now, it would be all high fives” – but, as he explains: “It wasn’t working out with Q-Prime any more, and we needed a bit more inspiration around us. Howard Kaufman had a different way of thinking, and when he took over, everything changed.”

The influence of Kaufman and his assistant Mike Kobayashi encouraged the band to think big again. “They genuinely believed in us,” Sav says, “and believed we should be on a bigger stage.”

This was exactly what transpired. Beginning in 2005, Def Leppard returned to playing major arenas, on a series of tours in the US and Europe on which they co-headlined with other famous rock acts including Journey, Whitesnake, Heart and Kiss. The logic for these packages was simple: “One plus one equals three,” as Joe puts it.

In 2006 the band gained renewed interest from rock radio in America with two tracks from the covers album Yeah! – versions of David Essex’s Rock On and Badfinger’s No Matter What. “That gave us our biggest US tour since Hysteria,” says Joe.

An album of original material, Songs From The Sparkle Lounge, was followed in 2008 by an American TV special, CMT Crossroads: Taylor Swift And Def Leppard, in which the young American singer performed live with one of her favourite bands.

“I think that opened a few people’s eyes,” Sav says. “It was a reminder that there’s more to this band than just heavy rock.”

There was one major setback the band needed to overcome along the way. Def Leppard’s contract with Universal Music had been fulfilled with Songs From The Sparkle Lounge, and no new deal was offered by them.

“All the momentum we’d been building up was scuppered by having a record company that didn’t want us any more,” Joe says. “The people at Universal back then were not on our side.”

As a live act they were flourishing; they were headliners at Download festival in 2009 and 2011. “People wanted to see us,” Viv says, “because we’re Def fucking Leppard and it’s going to be a hell of a show.” But as a recording act, a whole new MO was required.

“What we became then,” Joe says, “was effectively the biggest cottage industry on the planet.” He cites Marillion as a key example of a band that created a new business model after leaving major label EMI.

“I’ve got massive amounts of respect for Marillion and the way they did it,” he says. “They got their fans to pay for the album, and it gave them their own little niche. We never went into it like that, but we had our own record label, Bludgeon Riffola, that we could licence to whoever we wanted.”

Two Leppard albums were released via independent distributors: Mirrorball – Live & More in 2011, and Def Leppard in 2015. But during this period there was a change of personnel at Universal, and this was a key factor in persuading the band to return to the fold.

“We re-signed with Universal because new people have come in and they see the value in Def Leppard,” Joe explains. “Some of these people bought our records in the eighties. They understand.” This deal was one of the last that Howard Kaufman made in his long career. He died in January 2017 at the age of 79, leaving Mike Kobayashi to take the band forward.

“In this business it’s all about perception,” Joe says. “To get out of that rut that we’d been in, we had to make people look at the band in a different way, and so much of that was down to Howard and Mike.”

Now, with Diamond Star Halos arriving to great fanfare, and The Stadium Tour well underway, Def Leppard are where Kaufman and Kobayashi always said they should be.

In what is a big year all round for Def Leppard, they celebrate another landmark: the 45th anniversary of the band’s formation in 1977. From the original line-up, drummer Tony Kenning was the first to go. Rick Allen joined at the age of 15, but only after Frank Noon – who played drums on the band’s debut release, The Def Leppard E.P. – turned down the offer of a permanent gig.

Guitarist Pete Willis was fired during the recording of the third album, Pyromania, and was replaced by Phil Collen, previously a member of Girl – “The pretty boys of the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal”, as he fondly recalls. Vivian Campbell joined the band in 1992, a year after Steve Clark’s death. Def Leppard’s line-up has now remained unchanged for all of 30 years.

“There isn’t another band on the planet like this,” Viv says. “And what it comes down to is a collective sensibility. My two big experiences prior to Def Leppard were with Dio and Whitesnake, and neither situation worked out well for me. Ronnie James Dio named the band Dio, which tells you all you need to know. And Whitesnake: has there ever been a band in the entire history of rock music that’s had as many musicians pass through the turnstiles?

“If David Coverdale had only charged membership he’d be a gazillionaire! In Def Leppard it’s different. Joe isn’t your typical ego-driven singer. There’s more humility to it. We’re all in service of the music. And we all look after each other to a certain extent.”

He pauses and smiles. “I don’t mean to paint a false rosy picture. There’s been times when I’ve had an arm out in each direction stopping members of Def Leppard from fucking killing each other! Shit does happen, you know? But we all see the big picture. Whatever the problem, we work it out. And you can’t be an asshole in this band. There’s no latitude for that at all.”

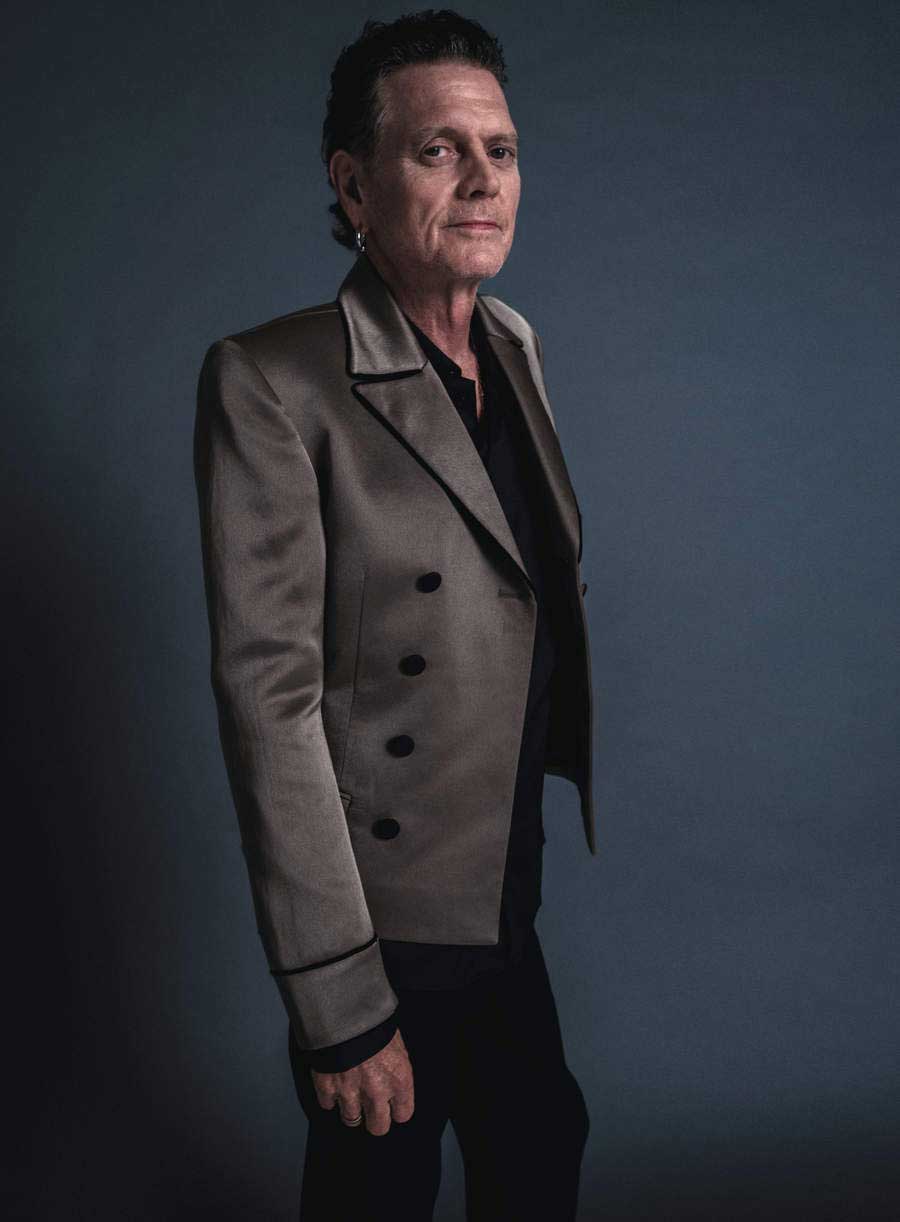

Joe and Sav, the two guys who’ve been in this band from the very start, are in some ways polar opposites. But, as Rick Allen sees it, they’re perfect foils for each other.

“Joe is the driving force, the life and soul of the band,” he says. “If you’ve got a microphone and big PA system, that’s licence to make a lot of noise. Sav, on the other hand, is really understated in many ways. Sav is really the thinker in the band.”

According to Sav, a typical band meeting goes like this: “Joe is so full of passion and will be very vocal, he’ll nail you to the wall. And if somebody else, usually Phil, has a different view, they’ll hammer it out for half an hour. I’ll sit there listening to it, and when they’ve worn each other out I’ll go: ‘Right, chaps, this is what we’re gonna do…’ And everybody goes: ‘Okay!’”

It’s when Sav elaborates on this role as band mediator that the spectre of Spinal Tap rises again. “What I do is what most bass players do,” he says. “Because they’re the bridge between the music and the rhythm, the bass player becomes the man in the middle.”

Tap bassist Derek Smalls said much the same, describing his bandmates as “like fire and ice”, and himself as the “lukewarm water” between them. Sav acknowledges the comparison with a laugh. “That is exactly how it is!”

Joe has his own joke about Sav: “We used to call him ‘Mr. Splinterbottom’, because he’d always sit on the fence.” Joe also agrees with what Rick Allen says about the band dynamic: “Everybody has their say, and that’s important. But when it comes to leadership, I’m deemed the captain.”

Joe is the voice of Def Leppard not only as singer but as spokesman-in-chief. “In pretty much every band it’s the singer’s job to do most of the interviews,” he says. “And talking till my tongue falls off is just something that I naturally do.”

A conversation with Joe is rarely brief, and always filled with funny, well-worn anecdotes. One is the story of his feud with early guitarist Pete Willis that began while playing football game Subbuteo, when Willis crushed one of Joe’s little plastic players by kneeling on it – “on purpose”, Joe claims, his feeling of betrayal still palpable.

Joe reckons that his propensity for talking comes from being an only child. “I had to have imaginary conversations,” he recalls. “And I won every argument, because teddy bears don’t talk back.”

He also feels that his life as a rock’n’roll singer was in some way pre-ordained. “I genuinely believe that certain people are destined to be certain things,” he says. “When I was a kid, I would sing Love Me Do into the vacuum cleaner handle because it looked like a microphone. These aren’t phantom memories – it’s what aunties and uncles have told me. And I gravitated to the radio – I crawled across the floor to get close to this sound. Music was an obsession for me. When the opportunity came to be in a band, I was already over-qualified.”

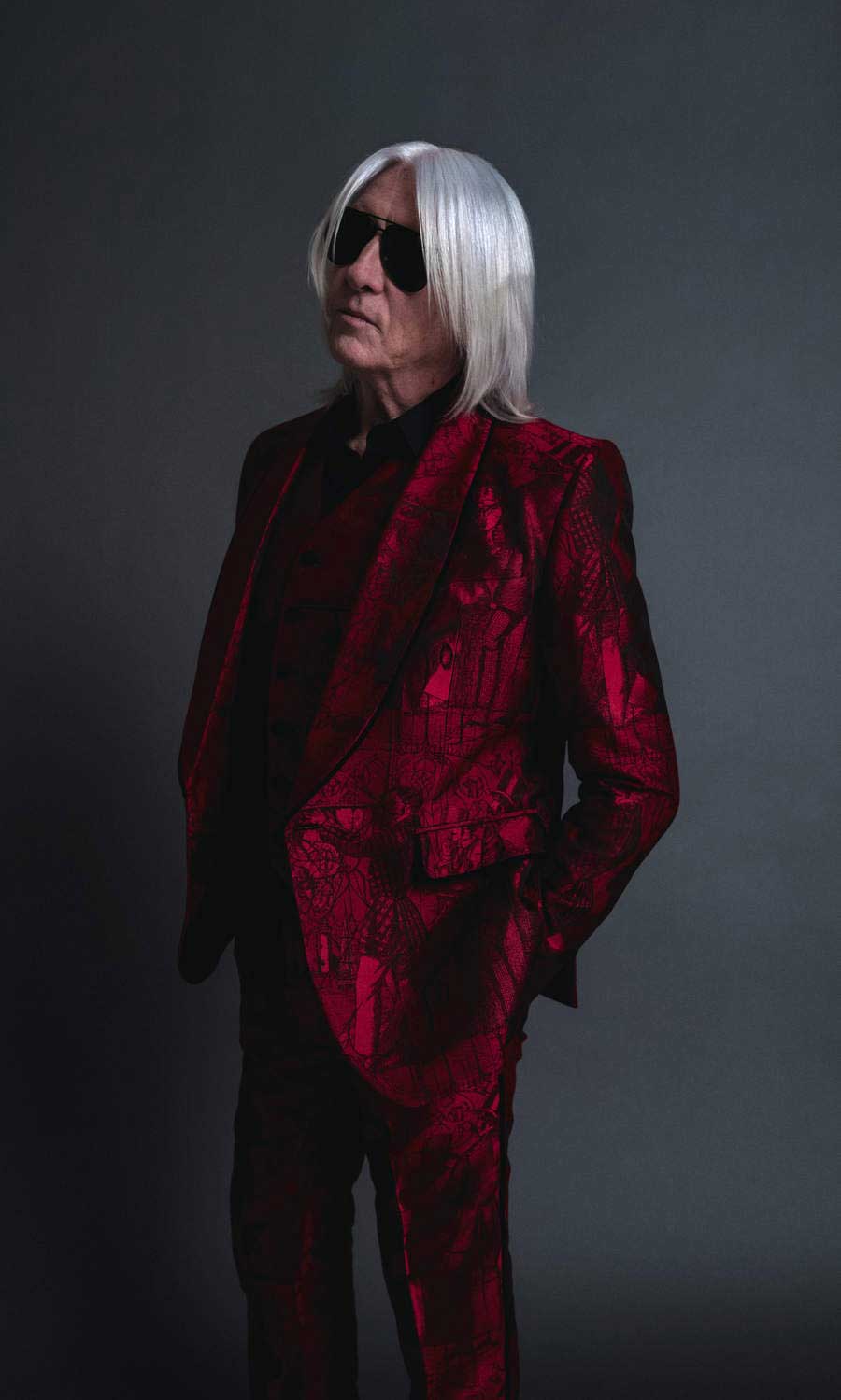

Phil Collen is the other dominant voice in Def Leppard. Less voluble than Joe, as most people are, but equally driven and opinionated. Off stage he speaks with a calm authority. It’s when he’s on stage that he likes to show off. As Rick Allen remembers of the night he saw Phil perform with Girl in the early 80s: “You could tell that he’d done a lot of work in front of the mirror. He had every fucking shape down, all the moves, beautiful balance, tons of confidence. And he’s the same now. He’s a rock star, you know?”

Hearing this comment brings a smile from Phil, but he reasons: “If you’re in a rock’n’roll band you’ve got to fucking King Kong it! I remember being blown away when I saw Van Halen in the seventies. David Lee Roth was such a showman. So when I’m up there playing, I’m not going to just stand there staring at my shoes.”

He also says that his ripped physique, displayed while shirtless on stage, is not merely for show. For a man of 64 it’s about wellbeing. After the wild years when he and Steve Clark were known as ‘The Terror Twins’ for their boozy antics, Phil quit drinking in 1986. Since then he has adopted a fitness regimen built around kick-boxing and a vegan diet. “I feel better now than I did in my twenties,” he says. “That helps when you’ve got a three-year-old.”

Rick Allen has the same quality that he sees in Sav: he’s a thinker. When he talks to Classic Rock, he enjoys telling the stories of his own wild years when he lived in Los Angeles in the early 90s. There was one occasion, he recalls, when he and a famous rock guitarist went at it for so long that the sprinklers in the garden came on three times before the session was done. But, with the life he’s had, there has been much for Rick to reflect on.

This is apparent when he talks about the serious stuff – most recently, when a period of isolation during the pandemic made him think long and hard about all the time he has spent on the road, and the impact this has had on those closest to him. “I realised that since the age of sixteen I’d had one summer off,” he says. “It felt so good to be at home with my family. I got to the point where I felt: I don’t miss my day job any more. But when we started working on the new songs, I knew how much this means to me.”

What Rick says about Vivian Campbell is a testament to the Irishman’s character. The band knew before Viv auditioned for them that he was a shit-hot guitar player, as he’d demonstrated at the age of 21 on Dio’s classic debut album Holy Diver. It was a bonus that he could also sing. But what mattered most, for a band in mourning for Steve Clark, was what kind of person could replace him. In that respect, Rick says: “Viv was the perfect choice. His playing is so tight, and that’s what he’s like as a person – solid.”

This strength of character is evident when Viv talks about what he went through in 2013, when he was diagnosed with cancer. “When you first hear that word, the bottom falls out of your world,” he says. “But once you get beyond that, you just deal with it. It’s all good now. I’m feeling great. But I don’t think that whole thing really changed me that profoundly. I think it cemented what I already believed. I wouldn’t say I’m fatalistic, but I’ve always been acutely aware that we’re on the clock. So I guess it amplified my world view.”

“It was such a shock when Viv told us he had cancer,” Joe says. “All we could do was give him as much support as we could.” It was what they did before with Rick Allen. What they tried, in vain, to do for Steve Clark. “We’ve had some dark times,” Sav says. “But the camaraderie in the band always pulled us through.”

They might not have made it this far. As Sav recalls, there was a terrifying incident in the mid-90s when Def Leppard might have suffered the same fate that befell Lynyrd Skynyrd in 1977, when that band’s private plane crashed, killing six members of the Skynyrd entourage including singer Ronnie Van Zant and guitarist Steve Gaines.

“We were flying from Shreveport, Louisiana to Chicago,” Sav recalls, “and the plane was getting hammered by this hailstorm. I heard the engines cut out, and we suddenly plummeted two thousand feet before it levelled out again. The stewardess was in tears, screaming for her life. I remember thinking: ‘We’re not going to survive this. This plane is going down.’ I felt this kind of serene acceptance that we’re going to die. And I remember thinking: ‘Bloody hell, after all the shit we’ve been through – the Steve stuff, the Rick stuff – it’s just fucking typical for us to die in a plane crash.’”

As he finishes this story, he can’t help but laugh. “There’s a certain black humour in it,” he says. But he also recognises something deeper in it: a sense that the hardest of times have in some way hardened their resolve.

“I’ve never really considered this before,” he says, “but on some sort of subconscious level there is that thing of sticking together through bad times. Is that a reason we’ve stayed together? I’m not sure. I still maintain that the real basis is that genuine love and understanding and respect of each other.

“You need to have an ego to be in a band, but you also need to understand who the other people are and to accept that we’re all different. It’s not something you can teach, but it’s what we have in this band. And really, I don’t understand why all bands aren’t like this one.”

“None of us are rocket scientists the way Queen were,” Joe says, “but, hey, we’re not stupid. The trick is knowing when to intervene, when to confront an issue, or just walk away.”

This is what holds Def Leppard together. What drives them on, Joe says, is what fuelled their dreams from the very start: “We wanted to be the biggest and the best rock band in the world. And that hasn’t changed. So when we make a new album, we damn well try to make sure it lives up to what we did before with Pyromania and Hysteria.”

He finishes this point with a comically overextended metaphor. “What we achieved with Hysteria – that’s one hell of an albatross around our necks,” he says. “But rather than think it’s something that’s dragging us down, let’s sit on its back and go for a ride!”

Phil Collen describes Diamond Star Halos as “a massive statement” from Def Leppard. “Most bands run out of ideas,” he says. “There’s this phrase: ‘ageing out’. Not literally, but they lose the fire. That’s not us. We have firepower. If ever people ask me if we’ve thought about knocking it on the head, I’m like: ‘Fuck no – we just got started!’ There’s a new power to the band now.”

For a band that was once, as Rick Allen put it, “as hip as haemorrhoids”, this is some turnaround. And according to Vivian Campbell, this is pretty much how Joe Elliott had it planned out all along.

“It’s not an accident,” Viv says. “When I joined the band, Joe talked to me about what he saw Def Leppard doing in the decades to come – and how he saw Leppard’s place in history as one of the quintessential British rock bands.” Joe thinks the word Rick Allen used – ‘rebirth’ – perfectly describes this new chapter in the Def Leppard story.

“That’s exactly how it feels,” he says, as another long conversation eventually reaches its end. “There’s no way a band can stay around as long as we have and not have some bad times along the way. But we’ve come through it all. We’re still here. We still set the bar high, and we still love doing what we do. It’s all about being the best that we can possibly be.”

Diamond Star Halos is out now, and the stadium tour continues - get tickets.