“Being in London’s nice. Let’s pull this blind up so that we can see some of the sky,” says Dhani Harrison, peering out from the Knightsbridge offices of Harrisongs music publishing company.

He’s just recently flown over from Los Angeles and is off to Berlin the following day to “touch base” with everyone about his remarkable debut solo album IN///PARALLEL. And while he apologises for still feeling a bit jet-lagged, his conversation is vivid and full of energy.

Back in 2002, Harrison helped to finish off his father George Harrison’s final and posthumously released album Brainwashed. He has continued to keep George’s name alive by playing his music, appearing at the Concert For George that year, and in a televised set to accompany his induction into the Rock’n’Roll Hall Of Fame in 2004, alongside Prince, Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne.

Further from the glare of the spotlight, he collaborates with a wide range of musicians, plays with Jonathan Bates in Big Black Delta and has been recording with his own band, thenewno2, since 2006. He’s also forging a career scoring soundtracks for film and TV. But IN///PARALLEL is something else, a genuinely progressive slice of 21st-century psychedelia with strong vocal melodies emerging from kaleidoscopic swirls of electronics, keyboards and strings, distorted guitars and percussion. Most importantly it’s his most deeply personal musical statement to date. And it has been a long time coming.

“I started working on it and had to keep putting it on hold as I had the score for a film or a TV show, because then you’re in another headspace and returning to this is like you’re in an inner world,” Harrison explains. “I liked the idea of doing a soundtrack. I started scoring without a picture, just by myself and I soon thought, ‘Wow, this is a lot of stuff, this is a big project.’”

Harrison played it as a work in progress to Paul Hicks, who is also in thenewno2, and with whom he also works on film and TV scores. “He said, ‘This is your solo album and you owe it to yourself to do it under your own name and not just try and hide it.’ It felt like it was time, so it happened very naturally.”

The music is suitably filmic. Some of the individual tracks are quite lengthy and all are packed with detail. And although some of the lyrical content is cryptic and will take some unravelling, as a whole it feels like a narrative comprised of related episodes. It concludes with the brooding Admiral Of Upside Down, with its initial sparsely picked guitar motif, which grows into a big finale before cutting dead. This lack of resolution is like watching a film whose inconclusive ending keeps you guessing and nags away inside your head.

“It has different acts. I heard the album in my head fully formed, but like when you edit a film, you don’t always go in chronological order,” says Harrison. “So where in the timeline does each song fit? It’s got to make sense. I was trying to work out the continuity, so it took a really long time to concentrate my mind hard enough to pull it out of the cloud. I’ve tried to get every single thing that I wanted to hear into it. And it’s certainly a real challenge arranging it to play live.”

Harrison has already recorded half of the record live for the radio station KCRW in Los Angeles with 16 musicians, including guest vocalists and a string section, and is looking forward to making a performance video of the whole record for syndication when he returns to LA.

The album features a number of musicians from other groups that he has worked with, including crucial contributions from vocalists Camila Grey and Mereki who duet with Harrison, and violinist Davide Rossi. “There’s always a female element to the story of the record so it helps having these wonderful singers around,” he says.

On London Water, an outburst of fuzz guitar and a “panic attack percussion section”, featuring Harrison and Stephen Perkins of Jane’s Addiction, leads to a tense section of ticking notes and sighing strings.

“I said to Davide Rossi, ‘Your part of this needs to be beautiful, so that one is going down into a panic attack and one is going into a beautiful sleep. You’re trying to hang on to the strings and not get scared.’”

He also incorporated a vocal line that had been going through his head when he’d been trying to sleep one evening.

Poseidon (Keep Me Safe) finds Harrison again playing with sounds and words on the edge of consciousness. Mereki opened a page of one of his books at random and at the track’s close she recites a paragraph in a whispery, background voice. “I won’t say the name of the book – see if anyone can work it out,” Harrison says.

He’s also been quoted as saying, “I had moments during the recording that changed my perspective on everything.” Can he elaborate?

“Nothing that I want to discuss in depth,” he replies. “But the world has had a couple of heavy years. 2015 was a rough year, then we all know what happened in 2016, and this year it’s been as if the world has been speeding up. The ‘in parallel’ thing comes from wondering where we might be if it had been a nice calm few years, and we would be in a different parallel universe to now. No one expected Prince, David Bowie, all these people to die in one go. And no one expected the climate in England and America to be where it is now.

“If you stay the same you don’t evolve, so I was forced to adapt. I spent a lot of time by myself meditating and I afforded myself a kind of clarity of self-reflection that allowed me to go back and correct some of the lines of programming in my brain that I didn’t like.

“If we’re all going to complain about the state of the world, what are you changing within yourself to become a higher vibrational being? Before you look after anyone else, you have to look after yourself; before you can love anyone else, you have to love yourself.

“I don’t want to sound preachy,” he continues. “It’s just kind of social, spiritual and emotional responsibility, and if there’s any message that I have it’s just to look at yourself, and if you work on yourself it spreads. It’s infectious in a good way.”

Harrison describes IN///PARALLEL, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, as “halfway between modern classical and grunge’n’bass”. There’s also something about the album that is reminiscent of Radiohead, both stylistically and perhaps more so in terms of it being a pretty radical shift, like the group made with Kid A and Amnesiac. In Harrison’s case, although there are recognisable elements from his previous work, he’s made a bold move from being essentially a “Travelling Wilburys sort of guy” who likes to make music in a room, into an explorer-in-music of inner states and landscapes of the self.

“I’ve always been a huge admirer of all the work that those guys do,” he says. “They have always been incredible musicians and so humble, they keep themselves to themselves and they don’t talk about music.

“And the same for Portishead. When you look at Geoff Barrow and the soundtracks that he’s done and Beth Gibbons, everything they do is amazing. I always think I talk too much about music – so I feel like I’ve already blown that one for myself,” he says, laughing.

“To be honest, you have to aim high to get to a place like where they are in their career. And wouldn’t that be amazing? But if that’s the kind of thing that you’re saying it evokes, then I’m very proud and very humbled to be mentioned in the same sentence as them. I wish I’d been afforded the same anonymity from the beginning, but because of Mother Nature, of where and how I grew up, obviously there was a lot more explaining to do.”

And without labouring the analogy, when Radiohead made that shift to produce Kid A and Amnesiac, those who thought they’d got a handle on their music were suddenly left scratching their heads.

“Yeah, totally,” Harrison says. “I feel like I didn’t understand some of their records and it made me mad for a few months and then I said, ‘Oh wait, this is my favourite album they’ve ever done.’ They were ahead of their own curve.”

Harrison has some regrets about giving up piano lessons as a child, but notes that this was because he could play better by ear than sight read. And now you can produce scores through notation software and sample banks. “If you can play it, they can play it,” he says.

Some of his soundtrack briefs have been to write string arrangements with an East meets West quality. He recalls watching in amazement as Ravi Shankar verbalised complicated instructions to the Indian classical musicians – whose tradition has no notation – in rehearsals for the Concert For George and how they responded immediately. He also recalls growing up listening to the work of another illustrious visitor to his father, the arranger Michael Kamen.

In terms of film soundtrack composers, Harrison is particularly a fan of Danny Elfman and Hans Zimmer. His first foray into movie soundtrack work was scoring Beautiful Creatures with thenewno2 – which he acknowledges as a lucky break. “You need to build a body of work and part of this project was to show people the expanses of what you can think about when you don’t have someone showing you the picture.”

Harrison grew up in the enormous 120-room mansion Friar Park, located near Henley-on-Thames, that George Harrison bought in 1970. Young Dhani’s favourite part of the whole estate was the studio that his father installed there in 1972, and where he ended up recording a significant chunk of IN///PARALLEL.

“I grew up above the studio – I was the studio rat, the bat in the belfry,” he says. “I was just there whether they liked it or not. And I guess that’s how every tea boy became a tape op and every tape op became an engineer and the engineer became a producer. You’ve just got to put in your 10,000 hours. I’m thankful every day to have been given that perspective.”

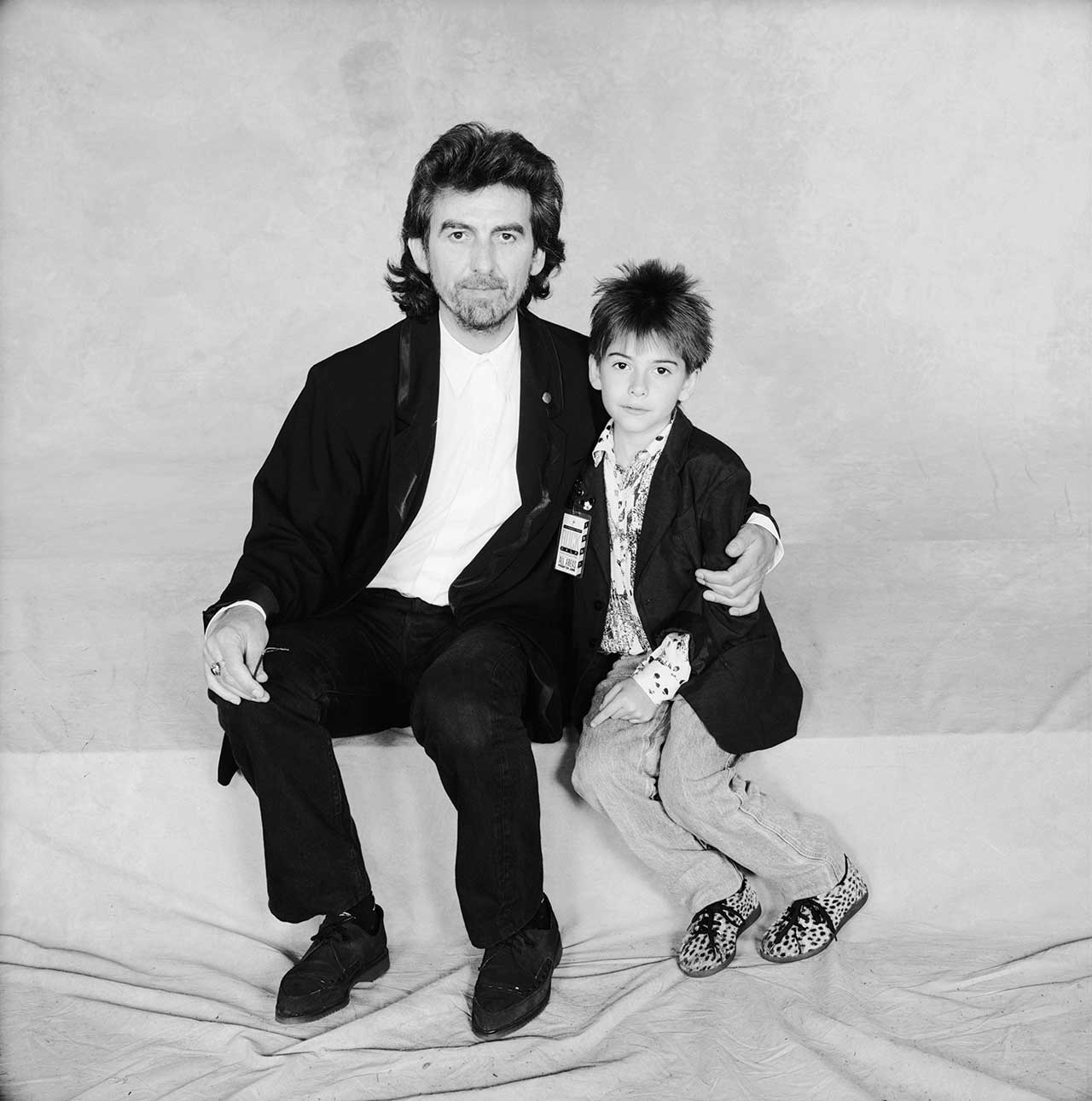

Talking to Harrison, it’s clear that although he loves to champion his father’s music, he is keen to be respected in his own right as a musician and composer. This lack of anonymity from being the son of one of the most famous musicians of all time runs to bearing a close physical resemblance to George and, hardly surprisingly, sharing some recognisable vocal inflections. This is the main reason he has deliberately hidden his name at times, as in calling his band thenewno2.

He’s philosophical about the fact that some people were “very quick to judge” when he was younger. Some, of course, found him wanting compared to his father’s legacy, while others expected him to do things in a certain way.

“It’s like, ’Hey, guess what? If you’re Michael Douglas you have something of your dad in you as well,’” he exclaims, laughing. “I think it can be seen as a negative sometimes in the music industry, whereas in Hollywood it can be a positive thing, so I just try to let the music speak for itself.

“A lot of people have a preconceived idea of the sort of music I’m going to make, of what it should be, and they’re just, ‘This is some weird shit’. But that’s because you had a preconception in your head. Maybe you imagined incorrectly what this would be, or maybe you still don’t like it. That’s fine. It’s just your opinion. It’s all just art.”

IN///PARALLEL is out now on BMG. See www.dhaniharrison.com for details.