Its torturous gestation, recorded in increasingly indolent sessions at Abbey Road across half a year, almost broke the band apart; as Roger Waters said in 1999, “The whole thing had fallen to pieces during Wish You Were Here.” It certainly paved the way for Pink Floyd’s third era – the final near-decade when Waters set himself up solely as bandleader, sidelining guitarist and co-writer David Gilmour, alienating drummer Nick Mason and ultimately dismissing founder keyboard player Richard Wright. It was the album on which, as Nicholas Schaffner spelled out so succinctly in his 1991 book Saucerful Of Secrets, “the Floyds, whether they realised it or not, were artistically at cross purposes. Gilmour and Wright were content that Pink Floyd’s music should keep transporting listeners into advanced states of REM. Waters was now determined… to wake them up.”

“The grimness may have been overstated as years have gone by,” Nick Mason chuckles down the line from California. “It wasn’t so much that it was truly grim, but we were just having great difficulty in getting to work on it.”

“In this post-Dark Side Of The Moon period, we were having to assess what we were in this business for,” Gilmour said in 2011. Suddenly having enough money to fulfil even the wildest teenage dreams proved problematic. Thanks to the all-conquering success of Dark Side…, expectations grew, and more and more people came to see their light show and as a result, it became a period where people talked solely about how many tons of equipment the group had and numbers of staff they had to operate their projections, rather than the music. Waters subsequently surmised, “The Dark Side Of The Moon finished the Pink Floyd off once and for all.” Gilmour was later to reply, “Roger has said that we may have been finished at that point, and he may have been right.” But Waters knew why the band stayed together: “We were frightened of the great ‘out there’ beyond the umbrella of this extraordinarily powerful and valuable trade name, Pink Floyd.”

Pink Floyd will forever now be seen in terms of the power struggle between Waters and Gilmour, and the period after Dark Side… saw the roots of this manifest themselves. All four of the group were coming to terms with their new-found success and a dawning realisation, as in some of the marriages that were breaking up around them, that the individuals who made up the institution had little in common.

Post-Dark Side..., we were having to assess what we were in this business for.

“We spent an awful lot of studio time faffing around…”

After the release of Dark Side… in March 1973, the band had fulfilled a US tour, and for the first time they had a significant amount of time off. The group’s lack of direction was underlined by their first post- Dark Side… experiment. This was a strikingly out-there project called Household Objects, and one which represented the band’s last foray into the experimental approach of Several Species Of Small Furry Animals Gathered Together In A Cave And Grooving With A Pict and Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast. With engineer Alan Parsons, they tried to make music using, um, household objects. Sessions continued through to December, but the idea was finally abandoned as unworkable.

“I remember spending an inordinately long time stretching rubber bands across matchboxes to get a bass sound – which just ended up sounding like a bass guitar!” Gilmour told me in 2002. When I enquired whose idea it was, he replied, “Probably Roger’s – it certainly wasn’t mine. We spent an awful lot of hours of wasted studio time faffing around.”

In fact, the next 18 months of Pink Floyd’s career could be encapsulated by the phrase ‘faffing around’. While Waters pondered the invisible world, the other members of the band grew their property portfolios, threw parties and generally bathed in the ennui of the newly rich. The Floyd brand was kept afloat with the release in early 1974 of A Nice Pair, a gathering of the group’s first two studio albums.

It was the long-arranged French tour in June that stirred the band, and as they decamped to the airless Unit Studios in London’s King’s Cross to rehearse, new material began to emerge. “It wasn’t really that oppressive,” Mason recalls. “I don’t think because you are making money you necessarily have to transfer into the Presidential Suite at the Holiday Inn – rehearsal rooms can be rough. I don’t think that’s ever been a bother for us.” It was here that Gilmour hit upon the four-note phrase that brought Waters to life. Inspired by Gilmour’s mercurial guitar work, Waters thought of Syd Barrett, the group’s original frontman, who had been dismissed six years previously and wrote a lyric about him, initially titling the song Shine On. At this time, the myth of Barrett had begun to grow disproportionately as his old band finally achieved enormous success on the back The Dark Side Of Moon. It was perhaps ironic that this success had been achieved via a newly augmented sound featuring saxophone and backing vocalists, ideas that Barrett had himself suggested back in 1967.

And Barrett’s growing mythology received a further boost around this time from a piece in the music press. In an era when journalists were only marginally less famous than the artists they wrote about, Nick Kent had written a lengthy feature, The Cracked Ballad of Syd Barrett, for the NME in April 1974, exploring the myths surrounding Floyd’s former leader.

By the end of the year, Harvest issued an LP set of Barrett’s two studio albums. It was to give Barrett his only US chart placing.

“PINK FLOYD’S AUDIENCE WOULD GLIDE OUT OF THE VENUE…”

Meanwhile, Floyd had worked up another song, Raving And Drooling during the rehearsals, in time for the French tour. There were new members in the camp: The Blackberries, Venetta Fields and Carlena Williams, who’d come to Gilmour’s attention singing with Humble Pie. Fields, who had no prior knowledge of Pink Floyd, noted the difference between the two groups. “The ’Pie were really rock and the audience would leave raging with lots of gusto,” she says today. “The Floyd’s audience would glide out of the venue, because the music mesmerised them.” Dick Parry returned on saxophone. All three would stay with the band for the next year and make an invaluable contribution to what would become Wish You Were Here.

The main focus of the year was the UK tour in November and December. By this time another new song had been written, You’ve Got To Be Crazy. The first half of the show was these three new numbers, the second half would be Dark Side…. The group spent three weeks in Elstree and a further week in King’s Cross rehearsing and getting to grips with the new projections that formed the now-famous film backdrops.

A 20-date tour ran from November 4 until the December 14, the last time they visited provincial cities such as Cardiff, Stoke-On-Trent and Bristol; they played three key London gigs in mid-November at Wembley. The Blackberries served to lighten the mood on the tour. “20 Feet From Stardom [a 2013 documentary about backing singers] is so typical,” Nick Mason laughs. “They were so good at riding the storm; if there was uproar, they were the ones who could sleep through it in the band room.”

It was the singers’ ability to rise above it all that impressed (after all, Fields had worked with the Stones and had been an Ikette).

“I was not into their politics,” Fields says. “I was so excited to be with a group with their music and popularity. I was used to singing with groups that sold out 15,000-seaters. Pink Floyd filled football stadiums throughout the world.” Reviews of the tour were mixed, including most notably, Nick Kent’s scathing NME report, which poured scorn on the band and called the three new songs “a dubious triumvirate”. Spirits in the Floyd camp going into the Christmas season were not joyous.

Everyone’s story about Syd’s appearance is different. But he was there and it was weird.

“THERE WERE ISSUES WITH OUR PERSONAL LIVES…”

Recording sessions for Wish You Were Here began on Monday, January 6 1975 in the new Studio Three at Abbey Road. If there was any sort of epiphany appropriate to this date in the band’s history, it was only that the sense of ennui

that they had experienced on the road had followed them into the studio. Brian Humphries – who’d first worked with the band on their 1969 soundtrack album More and had come in to look after the sound on their 1974 UK tour – was to be the album’s engineer. It was one of the first times EMI had worked with a freelancer. Because it was Pink Floyd, anything was allowed. “At first, I felt uncomfortable,” Humphries says. “I and the band were guinea pigs, being the first working in the new Studio Three, so we probably knew more about their desk than the boffins did, plus I wasn’t trying to outdo Alan Parsons, their blue-eyed boy.”

Humphries had worked with bands such as Free and Traffic: “I’ve always said that Traffic were my favourite band, but as for professionalism, the Floyd were the best, because the music was always going to be memorable when you heard the finished article.”

The problem was, simply, whether or not a finished article was going to happen. There were days when little happened at all. Mason was not happy about the isolation that multi-track recording offered, and how it drew out the process. Rick Wright, whose sound was so central to the band, seemed away in his own world. All four would take it in turns to arrive late.

“I don’t think they knew what they wanted to do,” Humphries told Sound On Sound. “We had a dartboard and an air rifle and we’d play these word games, sit around, get drunk, go home and return the next day.”

“It got a little desperate,” Mason recalls in 2015. “There were a few other issues with our personal lives.”

“Roger was taking on more of the way he wanted the band to go,” Humphries adds, “but David did have a lot of input in the decisions that were made.”

“It was clear to me that both Dave and Roger were in charge,” Fields recalls. “I loved Rick! He was quiet but very friendly. I loved the way he played piano. Nick was quiet as well.”

Gilmour wanted the record to be simply the three songs that they had been working on, making Shine On You Crazy Diamond as it was now known, a whole side of the vinyl. Waters thought it would sound cobbled together, and wanted it to be coherent.

“Dave wanted to make a completely different record, so we had a struggle about that, which I won eventually,” Waters told Prog Editor Jerry Ewing for Classic Rock in 1999. A band meeting, where Waters took notes, found him victorious – new material was to be written, and Raving And Drooling and You’ve Got To Be Crazy were mothballed (they were later resurrected as Sheep and Dogs, respectively, on 1977’s Animals album). Shine On… was to bookend the album and new material was to be added in between. And in referencing Barrett and the current state of the band, the theme was to be about absence. Storm Thorgerson, a frequent face at Abbey Road (“Argumentative, grumpy but a great ally when things got heated and a great sleeve designer,” – Humphries) set to work on the iconic designs that would so define the album.

It was once Shine On You Crazy Diamond got fully underway that the band began to coalesce. Like the way all four Beatles got together to demonstrate their professionalism when Billy Preston arrived at Apple to add keyboards on the Get Back sessions, so too did Floyd gather around Syd, their fifth member, although he wasn’t actually there. The new material matched the pre-written song. Welcome To The Machine, Waters’ scathing attack on the industry around him was written in the studio, while Have A Cigar, another swipe at music business fat cats was added. Frequent studio guest Roy Harper sang vocals after Gilmour and Waters failed to nail it, much to Waters’ later chagrin. Providing the humanity on the album was the title track, a bluesy confection that was accomplished in conveying feelings of longing. Waters’ failing marriage to Judy Trim fed into the lyrics, as did the state of the group and the now-legendary apparition of Barrett in the studio. Venetta Fields was thrilled with what she heard.

“I was impressed and amazed. Their music was mostly in minor keys, which made it dark and eerie.”

There were also some laughs to be had. The group-sanctioned visual gags that ran through their sleeves and projections, and also the cartoon programme for the 1974 UK tour demonstrated that Pink Floyd had a not-always-obvious funny bone.

“One of the nice things about the band was that there always was a sense of humour,” Mason says. “Although we were taken very seriously by the world at large, there was always an edge of fun. We were never known as a comedy quartet, the Crazy Gang make records, but within the band I think we had a lot of laughs.”

“Roger was the alpha-male but we all joined in quite heartily with the teasing,” Gilmour told Mojo in 2011.

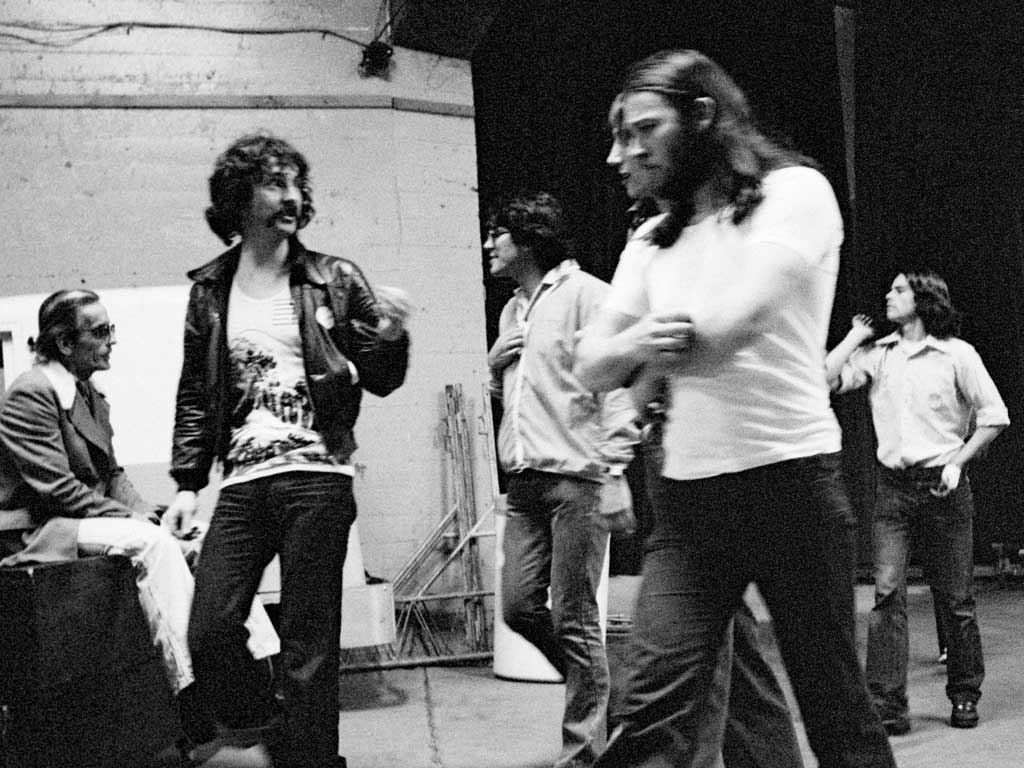

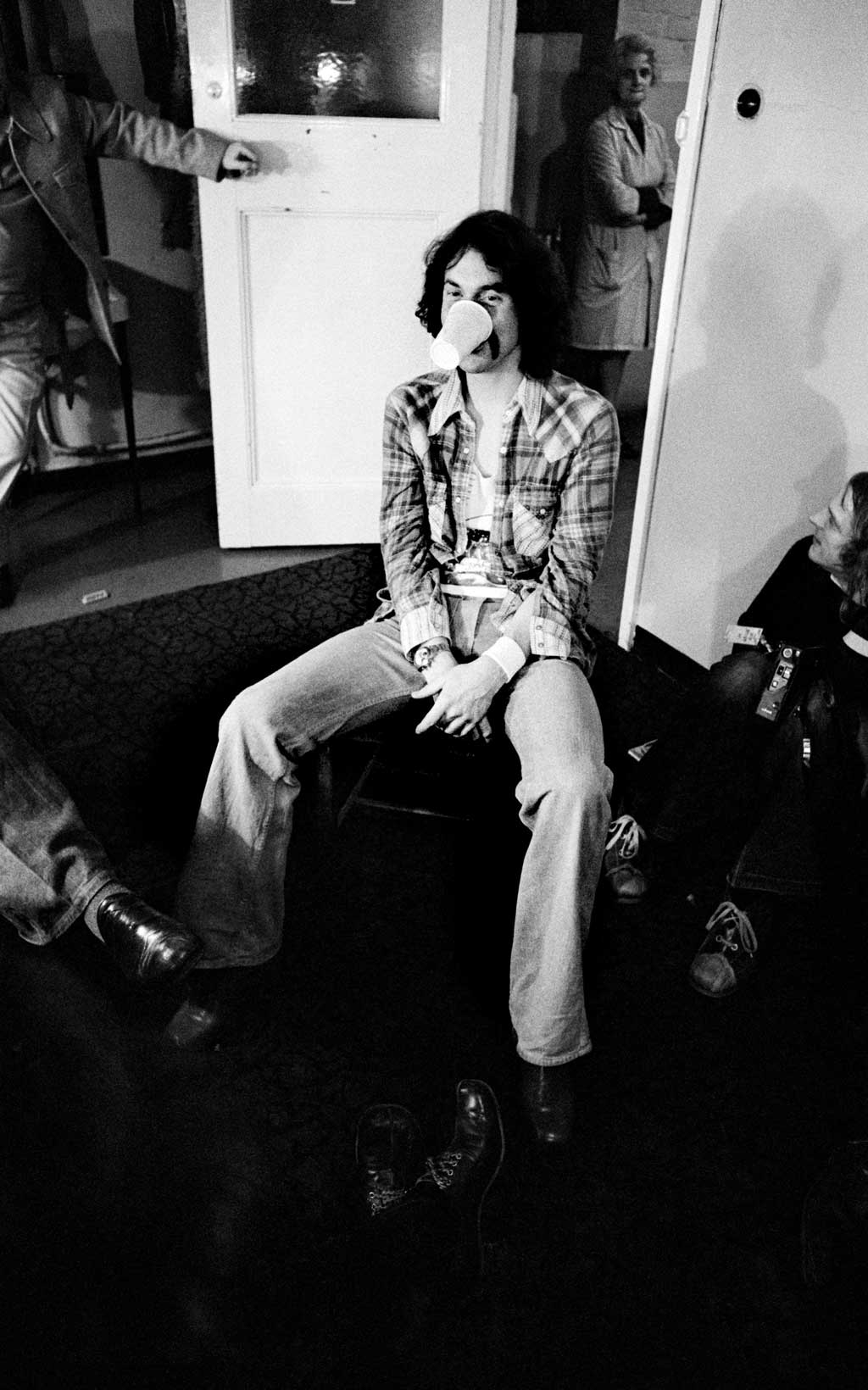

“I don’t think we realised that some people took it to heart a little more than others.” There was a great deal of banter, often directed at outsiders such as Humphries. (“It was always me versus them!” he laughs.) Jill Furmanovsky’s pictures from the sessions alternate between jollity (Waters eating her fairy cakes) and ennui (everyone looking a bit bloody miserable). Amid the laughs and the tears of the sessions, the band departed for an American tour in April 1975, and recording recommenced for one concerted month in May.

“NOBODY REALLY RECOGNISED SYD. I DIDN’T KNOW WHO HE WAS…”

Syd Barrett’s unannounced arrival at the recording sessions provided, in some ways, the ultimate affirmation that Waters had taken the right course with the album’s theme of absence.

So troubled an individual was he by this juncture – a clear five years after the band had last seen him – that he was there, but not there. Barrett’s return to Abbey Road on June 5 1975, allegedly during the playback of Shine On You Crazy Diamond, is the single event that defines the recording of Wish You Were Here.

As Mason said in his personal account of his time in Pink Floyd, Inside Out: “It is very easy to draw parallels with Peter Pan returning to find the house still there and the people changed. Did he expect to find us as we had been seven years earlier, ready to start to work with him again?”

“They never told me about Syd,” Venetta Fields, present on that day, says. “I read everything I know about him. Nobody really recognised him. I didn’t know who he was. They spoke to him for a while, and we got on with the session. I could see the impact he had on them that day. They were shocked to see him there, and really shocked at the way he looked and acted.”

So much has been said about his appearance. Mason adds in 2015, “Everyone’s story is fractionally different. Whether he came once, or twice, what he said, all the rest of it. All I can say is that he was definitely there, and it was weird.” The fact that Barrett was there at all is one of the key touchstones in the whole Pink Floyd story.

“THE BAND THOUGHT THEY NEEDED A BREAK. I KNOW I DID…”

With most of the album now finished, the band headed off for a tour of the US, culminating in their fabled Knebworth appearance in July 1975, which was dogged by technical issues. On the Monday after Knebworth the band returned to Abbey Road where they added the final touches to the album and mixed it.

Wish You Were Here was finally released in September 1975 – remarkably, and absolutely unheard of today, the band did no touring to support the release at all.

“We did two tours during its recording,” Brian Humphries concludes. “So perhaps they thought they needed a break. I know I did.”

Its reviews were infamously unkind. In the US, Ben Edmonds in Rolling Stone singled out Shine On… and said, “The potential of the idea goes unrealised; they give such a matter-of-fact reading of the goddamn thing that they might as

well be singing about Roger Waters’ brother-in-law getting a parking ticket.” Phonograph Record said that the album was, “Well crafted, pleasant, and utterly without challenge, it’s mood music for a new age.”

In the UK, Melody Maker said “the Floyd amble somnambulantly along their star-struck avenues arm in arm with some pallid ghost of creativity.” However, it mattered little what reviewers said. It went to Number One on both sides of the Atlantic and remains an enormous favourite.

So, can Wish You Were Here be seen as the album that ripped Pink Floyd apart? The real rip may have happened a decade later, but it was here the first tears were made.

There was a power struggle all the way through. It had been going on for years.

“There was a power struggle all the way through. It had been going on for years,” Gilmour told Jerry Ewing in 1999. “Roger wanted to be the leader and the boss and in charge – which he, de facto, was. But that didn’t prevent me, who did not want to be the leader, from thinking that I had a better knowledge or music sense in musical terms than he did. A better musical judgement. So my side of the supposed power struggle was to stubbornly try to cling on to certain musical values through all of this. But that obviously presented difficulties all the way through. But it certainly didn’t become an unworkable relationship.”

In retrospect, Nick Mason knows what the solution should have been. “Being wise after the event, what we should have done was to have done more touring of Dark Side Of The Moon, which I personally don’t think we did enough of, and then gone in much later, rather than going in soon afterwards and trying too hard at the time.”

“WISH YOU WERE HERE IS OUR MOST COMPLETE ALBUM IN SOME WAYS…”

All of Floyd’s inter-band tension and self-mythologising of this period was tremendously good for business and today, the appeal of Wish You Were Here simply grows and grows. It is the second album that new Floyd listeners tend to pick. Time has been very kind to the work: Gilmour has called Wish You Were Here Pink Floyd’s “most complete album in some ways”, and Waters has said, “It’s full of grief and anger, but also full of love.”

And now, on its 40th anniversary, Nick Mason – the only member of Pink Floyd who was there from the beginning to the end – concludes with this thought.

“I’d say happy birthday to myself, as I think it’s a lovely record. It’s so spread out after the intensity of Dark Side Of The Moon, it’s very of its time, and interesting that it remains one of our most popular records.”