In the autumn of 1991, while a whole generation pulled on plaid shirts and nodded out to the sounds of Nirvana’s Nevermind and Pearl Jam’s Ten, a smaller gang of people sat in the corner, grumbling to themselves.

As the tabloids and the fashion industry latched on to the new phenomenon that became known as ‘grunge’, the grumblers sneered and rolled their eyes. Now that their music was being listened to by everyone, it wasn’t special anymore. It was time to move on to the Next Big Thing.

In the technology market they call these people ‘Early Adopters’ – the people who’re always first to get their hands on the latest game console, iPhone, or app. The music world’s equivalent at the time were Dinosaur Jr fans.

Dinosaur were grunge before the word had even been applied to music. Their first album was released in 1985 – six years before Nirvana’s breakthrough album. Born out of the US hardcore punk scene, singer/guitarist J Mascis, bassist Lou Barlow and drummer Murph did the truly punk thing: instead of bashing out angry three-chord anthems, they reinvented hard rock, in all of its long-haired, psychedelic, wah-wah pedalled glory. Dinosaur Jr took the wasted country rock of Neil Young and the Stones, bolted a 500cc punk rock engine on to it, and filled the tank with heavy metal gasoline.

If they had a sound that could flatten all in its path, at its heart were Mascis’s vocals: bruised, yearning and sweet. As Nirvana biographer Everett True wrote: “Their first album Dinosaur appeared in 1985 in a US postpunk underground climate that favoured short, acerbic bursts of noise over anything. Just when everyone reviled the 70s as being a decade of dinosaur (ha!) bands, here were J and Lou and drummer Murph to reinvent a whole musical genre. Suddenly it was hip to like Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Allman Brothers again: something Seattle bands like Mudhoney doubtless appreciated a few years later… [They were] the band who inspired Teenage Fanclub, Nirvana, Buffalo Tom, Lemonheads and… thousands.”

While bands like Alice In Chains and Soundgarden benefitted from their association with the Nirvana supernova, Dinosaur Jr’s lot remained unchanged. Internal squabbles meant that Barlow was gone by the time they were snapped up by a major for patchy fourth album Green Mind. If some thought that the magic had been lost with Barlow’s departure, storming follow-up Where You Been showed otherwise. Drummer Murph was out by 1994’s Without A Sound and only one more Dino album followed (1997’s Hand It Over), before Mascis retired the name in favour of recording as a solo artist. While contemporaries like Dave Grohl and Chris Cornell soared to new heights, Mascis seemed to disappear even further into obscurity, contributing to film soundtracks, and producing two patchy solo albums.

And then, just when you’ve almost forgotten about him, he reforms the original Dinosaur Jr and makes one of the best alt.rock albums of 2007: Beyond.

Mascis sits awkwardly in a hotel in Knightsbridge, sipping on a Starbucks coffee. J (just ‘J’: his first, never used, name is Joseph) has a reputation as one of rock’s most difficult interviewees. Look at any previous interviews with him and you’ll find a huge collection of one-word answers, awkward pauses and bemused or offended music hacks.

“People would say something and I’d take a little while to answer,” he drawls, “but really their mind is going really fast and suddenly they’re like already writing me off before I answer. They’re like ‘He’s an asshole, he won’t talk’ and – fuck that – by the time I answer I’ve already been written off.”

Like his music, Mascis can seem blank, apathetic, stoned. Which is quite amazing for a guy who rarely drinks and never takes drugs. “People have always thought I was stoned,” he says. “From since I can remember. I come from, like, a hippy kind of town [Amherst, Massachusetts: home of poets Emily Dickinson and Robert Frost]. There’s a lot of drugs and stuff. Pot and acid are the big drugs, but I was never really big on drugs: that’s why I related to the straight-edge. I heard that song by Minor Threat and it was exactly where I was at.”

Minor Threat’s Straight Edge – the song that gave its name to the puritanical anti-drink and drugs lifestyle that emerged in the US hardcore movement of the 1980s – includes lyrics like, ‘I’m a person just like you/But I’ve got better things to do/ Than sit around and fuck my head/Hang out with the living dead/Snort white shit up my nose/Pass out at the shows’.

Mascis had already developed a similar disgust for drug-users. “Hanging out my whole life with all these hippies and seeing these acid casualties walking around town – I was sickened by the whole thing,” says J. “I was not into drugs at all by the time I was 14. I’d tried them and decided that it was stupid. Murph was the first person I knew who went to rehab – his parents made him go for pot…”

Classic Rock chuckles. “He did smoke a lot of pot,” he admits, almost smiling. “But it was kind of weird.”

Living in a small town with a hippy culture gave the young Mascis a unique slant on music, soaking up everything from Venom to New Order, Dio to Discharge. While most teenagers were choosing their musical tribe and sticking with it for fear of ridicule, Mascis and his mates felt no such pressure.

”We were the only kids into hardcore in, like, a hundred miles,” he says. “We didn’t interact with any other people like us from day to day. I could get into The Exploited and [notorious neo-nazi UK punks] Skrewdriver and stuff cos I had no idea – they just sounded pretty cool. People in England would associate those bands with some politics or some scene. We had no context to put anything into.

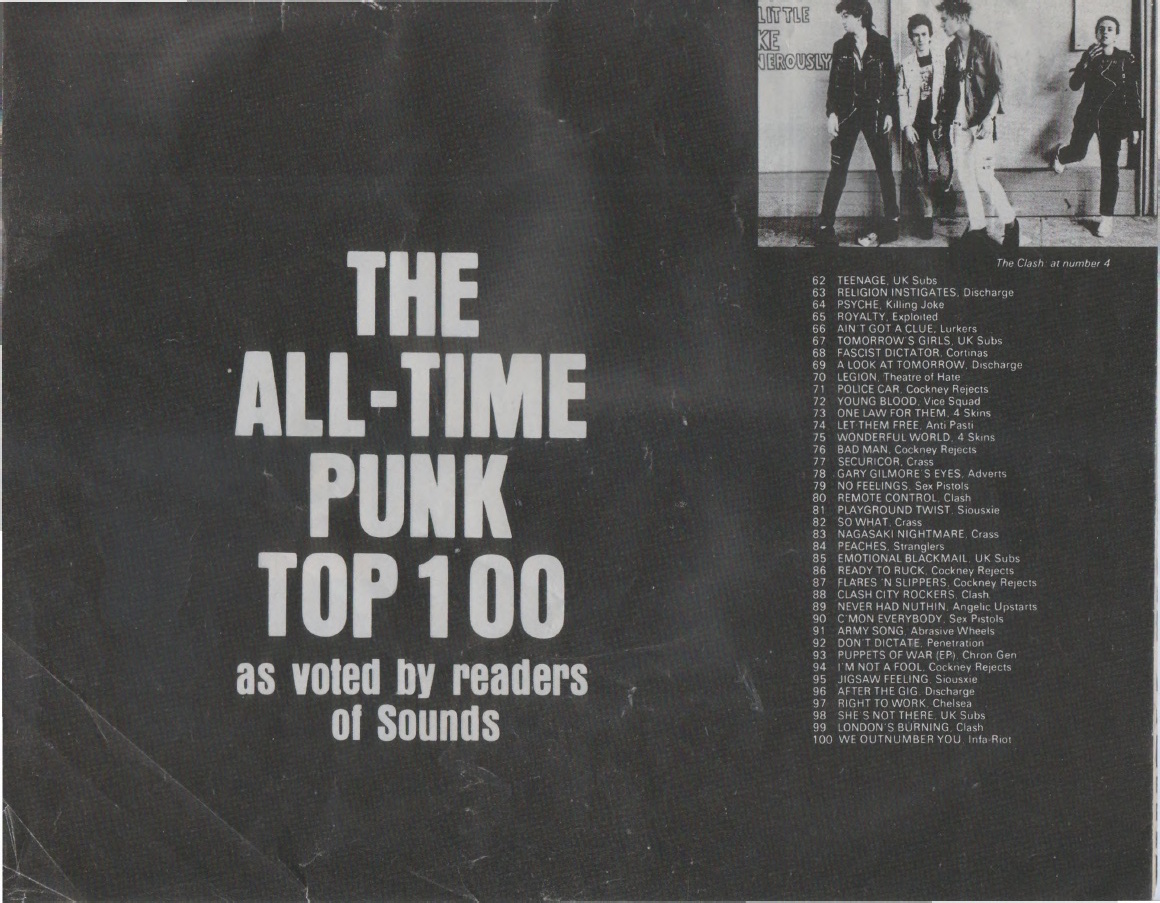

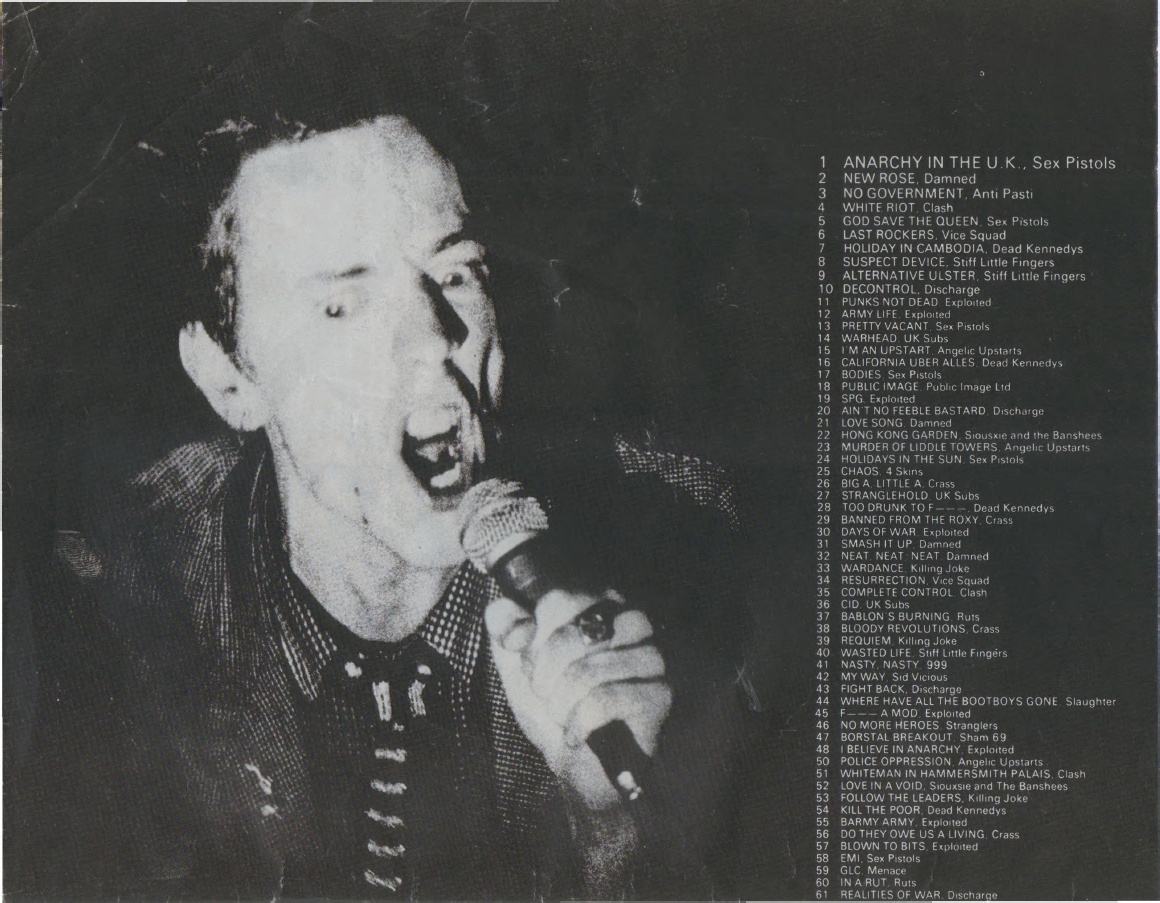

“I remember this magazine from Sounds called Punk’s Not Dead – it had, like, the 100 Greatest Punk Songs. And at that point it was the Discharge and Blitz kind of era. So it had the first, second and third generation of punk. And I tried to collect all 100. I think I have them all. I don’t know where I got the money for all those records. Like, I’d steal from my mom and stuff.”

At the same time, the young Mascis had a growing interest in metal. “But only like certain metal was cool,” he says, “like Venom or Motörhead, you know, Merciful Fate. Stuff like Queensrÿche, I hated – it was horrible. There was some metal that was kind of more punk. Like I saw Metallica with Queensrÿche and WASP or somebody. The other bands were horrible, but Metallica were good at that point…”

When Mascis and Barlow’s hardcore band Deep Wound split, they recruited Murph and J moved from drums to vocals and guitar as the three of them set about creating something a little bit more interesting. Something hairier and greasier and featuring long, loud guitar solos. Mostly because Mascis couldn’t really play anything else.

“I just always liked guitar solos,” he says with a shrug. “Whenever I picked up a guitar I would always play solos. I didn’t know how to play chords really. And I couldn’t play barre chords. When I played drums I liked playing a lot of fills and stuff – it’s just a way of expression.”

Long-haired guys playing wailing guitar solos would seem like an obvious way to wind-up the punk rock purists. “Yeah, people hated everything about it,” he says. “And they hated us cause we were also kind of country-sounding. But that was our only possible fanbase, so we didn’t have anything…

So why didn’t they try and appeal to that crowd?

“I was just always kind of a dick,” he says. “I didn’t care about appealing to anyone. I just wanted to amuse myself, I guess. And hardcore was over at that point. It seemed like a definite ending point.”

It was. A new generation had witnessed hardcore’s earnest pissing in the wind and, like, decided that it wasn’t worth getting upset about, maaan. The tide had turned. When it finally crashed on the shore in 1991, it spewed up Nevermind, Douglas Coupland’s novel Generation X and Richard Linklater’s movie, Slacker: all works about a disaffected, screwed-up generation that fed off pop culture, sneered at idealism, worked in ‘McJobs’ and realised that they were never going to be as successful as their parents.

Oh well, whatever, never mind.

Where Nirvana still had the energy to be angsty and angry, Dinosaur Jr were the perfect Generation X band: apathetic, lazy, jaded. Their song titles said it all – Yeah We Know, How’d You Pin That One On Me, What Else Is New, Yeah Right – these truly were songs for the jilted generation: a group of people who had nothing much to say, nothing much to be angry about, nothing much to look forward to.

“Yeah,” nods Mascis. “We’re not happy and we’re not sure why. There’s nothing concrete that we could be pissed off about. There’s no war and we’re not starving or anything and we shouldn’t have any particular problems, but we’re still miserable somehow. I was kind of always envious of people who had more concrete problems cos at least they had some excuse – y’know like they were beaten as a child or something – but I’m still miserable and I had none.”

The band’s disfunctionality led to the original split with Barlow. And although the Barlow-less Dinos arguably hit greater heights (the first three albums get all the critical acclaim, but Where You Been is probably the greatest and most consistent and it and follow-up Without A Sound were their only albums to crack the UK Top 30), it seems that even alt. rockers can’t resist the reunion bug.

A cynic might suggest that seeing contemporaries like the Pixies bury the hatchet, rake in the dollars and enjoy elder statesmen status at the same time, must have helped smooth things between Lou, Murph and J – but J genuinely doesn’t seem to care about such things. And, unlike the Pixies, they made an album first. If it doesn’t quite take them back to their previous highs, tracks like This Is All I Came To Do and Been There All The Time are more than worthy additions to the Dinosaur canon. And who could begrudge them a happy ending?

“We just have a certain sound and energy together,” explains Mascis. “Also there are so many bands around now and so many of them are mediocre – they just have to look good now or something. At our worst, we still sound better than a lot of them.”