You know him, right? Shiny-suited prog traitor. Ruined Led Zeppelin. Wife ran off with the decorator. All true. But there’s way more to the man who nearly joined The Who, once considered suicide and is, in all honesty, a Thoroughly Misunderstood Chap.

Ancient tape machines clutter the upper corridors of Abbey Road Studios. They’re the clunky old contraptions, with big metal spools, that would have been pressed into service for his first recordings. At the age of 18, in 1969, he was in a rock band that had elaborate songs about the moon landing. A year later he was in a room downstairs in this very building, playing on a George Harrison album.

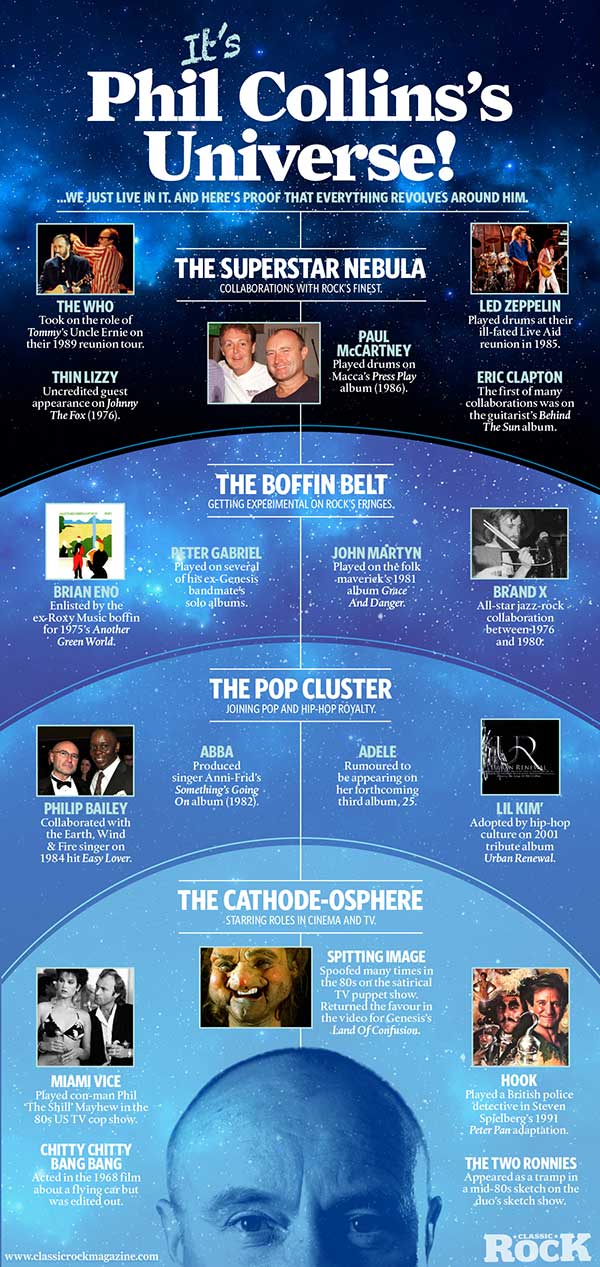

He started early, Phil Collins, and he’s crammed a lot in. When still only 20, he signed up as the denim-dungareed drummer with Genesis. He ended his tenure with them as their satin-jacketed singer, and went on to release the eight solo albums now resurfacing in extended and remastered versions in a reissue project called Take A Look At Me Now. There was also a sideline in production, working with everyone from John Martyn and the Four Tops to Adam Ant and Tears For Fears.

He’s weathered every storm imaginable; one minute the revered godhead of atmospheric popsoul, the next lambasted as a mawkish balladeer, his two-continent appearance at Live Aid pouring petrol on the critical flames. But in the typically cyclical nature of fashion, a raft of American rock and R&B stars are now sampling and loudly applauding the very records that were supposedly over-processed and disagreeable 30 years ago.

Today Phil Collins is in a little side-room that contains only two chairs, a small table, him and his can of Red Bull. He has the thickest, most muscular arms imaginable, and two main emotional gears: when we talk about music and the people he’s worked with, he lights up like a pinball machine – “I haven’t thought about this for years!”; when we touch on that famous critical pasting or the sad recent events of his private life, he seems to shrink in size, so crestfallen and preoccupied that he’s like a completely different person.

“You ask it,” he says, raising his Red Bull, “and I’ll answer it.”

I can remember everything about seeing Genesis at Farnborough Tech on May 29, 1972, including a stupendous version of The Return Of The Giant Hogweed. Can you remember anything about it?

Yeah. It was good times. We played Farnborough quite often. It was always friendly, as some of the guys were from that neck of the woods. We did the Great Western Festival in Lincoln two days later, and I remember meeting the promoter, Stanley Baker, on the Embankment somewhere. He had a lovely penthouse overlooking the river. He’d been in Zulu with Michael Caine, so that was a real star.

There’s an elite club of former child actors who played the Artful Dodger in Oliver! when they were kids and went on to be rock stars: you, Steve Marriott, Davy Jones of The Monkees and Robbie Williams. Do you think you had anything in common?*

My manager once said Robbie Williams was a new version of me, a ‘cheeky chappie’. Stevie Marriott and Davy Jones, yes – it was a great part if you were a precocious kid.

How did you get to be in The Beatles’ film A Hard Day’s Night?

Well I was in it, but not in it. Walter Shenson [the producer] asked me to narrate a ‘Making Of’ DVD for its 30th anniversary in 1994. And I said: “I was in it but they cut me out.” And he gave me the outtakes of the concert scene at the end and I went through it frame by frame and I found myself! And on the DVD I circle myself on the screen. I was thirteen. I was also in I’ve Got A Horse, a Billy Fury movie which has the Small Faces in it, but I didn’t finish up in the film. And I was edited out of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. So yes, there’s pattern here.

But I did Buster later on. And I played Uncle Ernie in Tommy, which I loved doing though it was very politically incorrect – playing a paedophile. But it was great cos I was with The Who. I was working with Townshend just after Moon died, and I said to him: “Have you got anybody to play the drums? Cos I’d love to do it. I’ll leave Genesis.” And Pete said: “Fuck, we’ve just asked Kenney Jones.” Cos Kenney Jones, unbeknown to most people, played on stuff when Keith was too out of it. He was far too polite for The Who. But I would have done the job. I would have joined them.

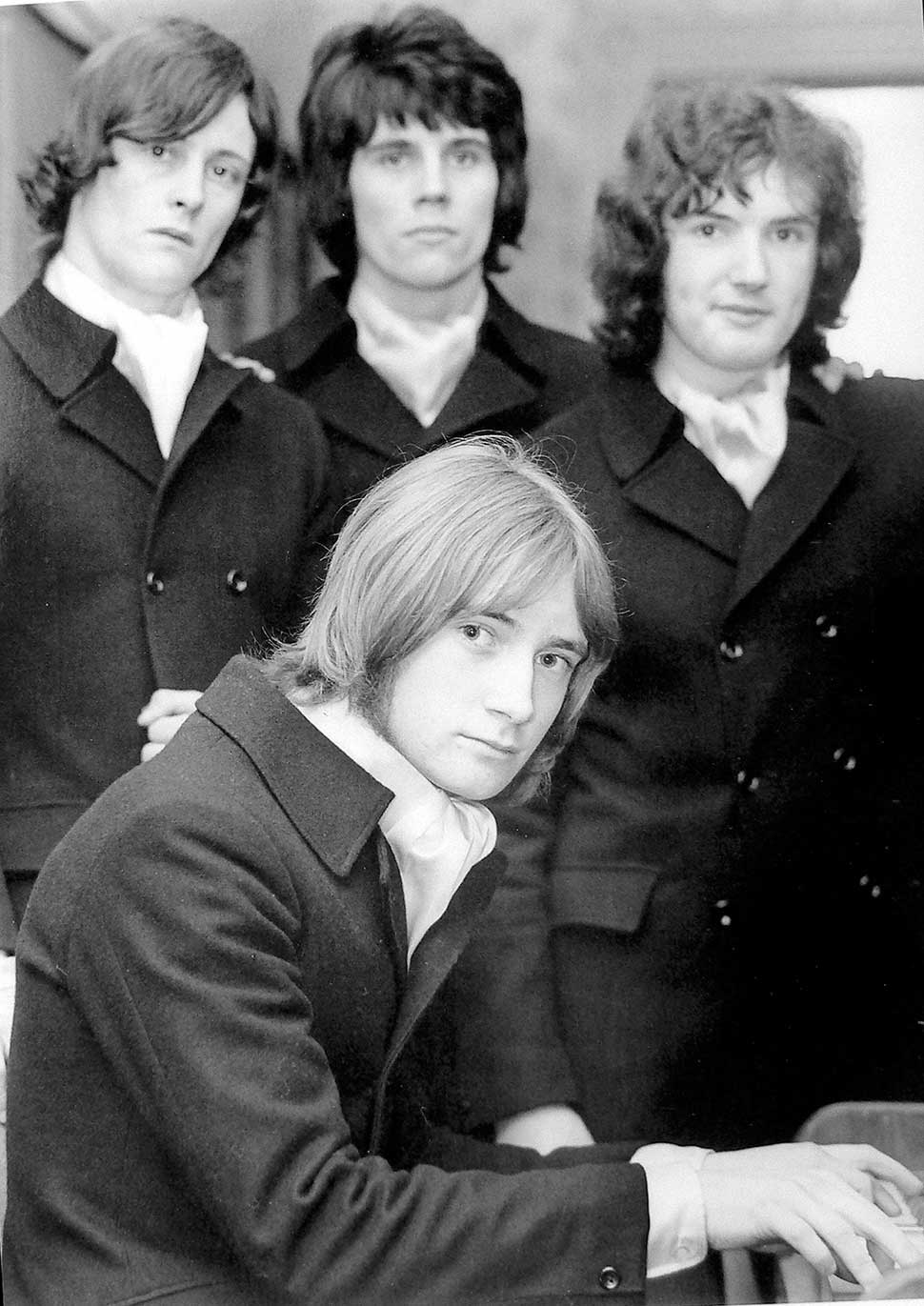

The band you joined when you were nineteen, Hickory, made a concept album about the moon landing. You couldn’t make it up. How 1969 is that?

Yeah, it was. I remember it all. We were called Hickory, and then became Flaming Youth. Ken Howard and Alan Blakely were the writers – they wrote for The Herd and Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich. And, being a gay couple, they’d taken a shine to our keyboard player, who drank at this club in Warren Street. And they were looking for a band to do this concept album they’d written. I said: “I’m in a band.” And they came to see us at Eel Pie Island, and they liked us so we did it.

How did you get to play on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass?

That was when I was in Flaming Youth. Our manager got a call from Ringo Starr’s chauffeur, who said they needed a percussionist, and he suggested me. So I went down to Abbey Road and Harrison was there and Ringo and Billy Preston and Klaus Voormann and Phil Spector, and we started routining the song. No one told me what to play, and every time they started the song, Phil Spector would say: “Let’s hear guitar and drums,” or “Let’s hear bass and drums.” And I’m not a conga player, so my hands are starting to bleed. And I’m cadging cigarettes off Ringo – I don’t even smoke, I just felt nervous.

Anyway, after about two hours of this, Phil Spector says: “Okay congas, you play this time.” And I’d had my mic off, so everybody laughed, but my hands were shot. And just after that they all disappeared – someone said they were watching TV or something – and I was told I could go. A few months later I buy the album from my local record shop, look at the sleeve notes and I’m not there. And I’m thinking: “There must be some mistake!” But it’s a different version of the song, and I’m not on it.

Edited out yet again.

Yeah but worse – there’s more! Cut to years later. I bought [former F1 driver] Jackie Stewart’s house. And Harrison was a friend of Jackie’s, and Jackie told me George was remixing All Things Must Pass. And he said: “You were on it, weren’t you?” And I said: “Well I was there.” Two days later a tape’s delivered from George Harrison with a note saying: “Could this be you?”

I rush off and listen to it, and straight away I recognise it. Suddenly the congas come in – too loud and just awful. And at the end of the tape you hear George Harrison saying: “Hey, Phil, can we try another without the conga player?” So now I know, they didn’t go off to watch TV, they went somewhere and said: “Get rid of him,” cos I was playing so badly. And then Jackie rings and says: “I’ve got someone here to speak to you,” and puts George on and he says: “Did you get the tape?” And I said: “I now realise I was fired by a Beatle.” And he says: “Don’t worry, it was a piss-take. I got Ray Cooper to play really badly and we dubbed it on. Thought you’d like it!” I said: “You fucking bastard!”

All that effort for one little gag. Wonderful!

It was lovely, wasn’t it? [laughs]

On that bill in 1972, Genesis played with Atomic Rooster, Vinegar Joe, Humble Pie and Wishbone Ash. I always imagined the rock underground were all in it together. Was there any sense of rivalry?

We were in it together, yeah. You didn’t feel threatened by anybody. It was the days when you’d bump into people at Watford Gap [service station on the M1]. We did the Six Bob Tour – six shillings to see three bands: us, Lindisfarne and Van der Graaf Generator. We went on first, then Lindisfarne brought the house down every night – Newcastle band, singalongs – and then Van der Graaf came on and it all went very dark. We shared a coach together and we all got on very well. It’s funny to think about [smiles fondly]. I don’t often think of those days.

How did it feel to be suddenly out front in Genesis?

I felt exposed. I’d lived all my life behind the security blanket of a drum kit, and suddenly there was nothing except a microphone stand. And the band sounds different from out front. You hear a different kind of balance out front, and it isn’t comfortable. And I didn’t want the job, frankly.

Why not?

I wanted to stay the drummer. We had people down every Monday [auditioning], five or six people, and I would teach them what they had to do. We were writing A Trick Of The Tail and I would teach them some old songs – Firth Of Fifth or whatever – and I ended up sounding better than anyone else. And this [Genesis] was kind of a family. “Do we want this person in our family? Will he fit in with the way we do things?” Anyway, we didn’t find anybody and ended up with me.

You’d grown up listening to pop music and Motown, but I remember people being surprised when you released In The Air Tonight in 1981: “Phil Collins is rock musician, but isn’t this a pop ballad with synthesizers?”

Face Value had a huge variety of songs on it. I was listening to The Beatles, Count Basie, Weather Report, Earth Wind & Fire, Neil Young… They all featured in my life, so I kind of wrote songs like them. I remember doing In The Air Tonight at Live Aid and Townshend saying: “Are you going to do that fucking song again?” as it was the only one I ever played.

Why did so many people connect with Face Value?

Well, it was a very personal album, and I said it like it was. The romantic songs were heart-on-sleeve. The lyrics of the songs were real. I didn’t hide it – ‘You’ve taken everything else.’ You know what I mean?

So they identified with the heartbreak, the divorce?

[Theatrical mock-sorrow] Oh please, don’t mention that! Yeah, people identified with it.

Did they identify with you playing In The Air Tonight on Top Of The Pops with a paint pot and brush on your drum machine as a message to your wife, who’d gone off with your interior decorator?

All these stories come up and there’s never enough time to talk about them properly. What happened was I didn’t know what to do on Top Of The Pops. I didn’t want to just stand there and sing cos of all that insecurity, so I thought: “I’ll play the keyboard.” But I didn’t want one of those poncey Duran Duran things on a stand. So I got a Black & Decker Workmate, and a drum machine on a tea chest. So there was a theme there.

So people just assumed it was about the bloke who went off with your wife?

Well she certainly did. I improvised the lyrics to In The Air Tonight and wrote them on a sheet of paper. And when I turned it over, weirdly, it was the letter-headed notepaper from the painter and decorator. She took great umbrage, my ex-wife, at me writing about anything like this. She didn’t like the way I was giving people my side of the story. But I didn’t colour it any way.

Musicians respected you but the press weren’t always as kind. One critic said: “Phil Collins has been guilty of placing the bullseye on his own forehead” – a reference to the Concorde caper at Live Aid – “and after Another Day In Paradise he was a purveyor of tortured romantic ballads for the middle-income world.” How did you react to things like that at the time?

I didn’t understand it. I know what I meant with Another Day In Paradise, but people took offence to it because I was rich. What I was saying is that we should all be very appreciative of whatever we’ve got, as we’re all doing better than that. But they all took offence at it.

With Concorde it looked like I was showing off. I’d played on Robert Plant’s solo records and he said: “Are you doing this Live Aid thing?” And I said: “Yeah.” And he said: “Can you get me on it? [US promoter] Bill Graham doesn’t like me and he doesn’t like Zeppelin. Maybe you, me and Jimmy can do something?” And I said: “Great, yeah.” And then Sting called me and said: “Can we do something together?” [UK promoter] Harvey Goldsmith said: “You can get Concorde and play both.” I said: “Well, okay, if it can be done.” I didn’t think I’d be showing off.

By the time I got there, me and Robert and Jimmy playing together had become The Second Coming Of Led Zeppelin – John Paul Jones was there too. Jimmy says: “We need to rehearse.” And I said: “Can’t we just go on stage and have a play?” So I didn’t rehearse when I got there, but I listened to Stairway To Heaven on Concorde. I arrived and went to the caravans, and Robert said: “Jimmy Page is belligerent.” Page says: “We’ve been rehearsing!” And I said: “I saw your first gig in London, I know the stuff!” He says: “Alright, how does it go, then?”

So I sort of… [mimes the Stairway To Heaven drum part], and Page says: “No, it doesn’t! It doesn’t go like that!” So I had a word with [co-drummer] Tony Thompson – cos I’ve played as two drummers a lot and it can be a train wreck – and I say: “Let’s stay out of each other’s way and play simple.”

Thompson, rest his soul, had rehearsed for a week, and I’m about to steal his thunder – the famous drummer’s arrived! – and he kind of did what he wanted to do. Robert wasn’t match-fit. And if I could have walked off, I would have done, cos I wasn’t needed and I felt like a spare part.

So you could tell it was going badly?

Yeah, frankly. But we’d all have been talking for thirty years about why I walked off stage if I’d done it, so I stayed there. Anyway, we came off, and we got interviewed by MTV. And Robert is a diamond, but when those guys get together a black cloud appears. Then Page says: “One drummer was halfway across the Atlantic and didn’t know the stuff.” And I got pissed off. Maybe I didn’t know it as well as he’d like me to have done, but… I became the flagship, and it looked like I was showing off.

Why did you let this kind of criticism affect you so much?

Because you tend to beat yourself up. You start to think you are the things people say you are. Things like that review you just read me of Another Day In Paradise [shakes his head]. I should be over that by now, but it still puts the hackles up occasionally.

You’ve worked with such a variety of great people – Thin Lizzy, Adam Ant, Tears For Fears, Anni-Frid from ABBA, to name just four. Why did you go for those four?

I kind of knew Phil Lynott. He lived with one of our tour managers, that’s how I got the call. Adam Ant – funny guy, lovely guy! Tears For Fears just wanted me to do that big drum thing from In The Air Tonight on Woman In Chains – “We want you to come in here in a big way.” Frida flew over to the Genesis studio to meet me – it’s so interesting for me to talk about this sort of stuff! – and she was ever so nice.

She thought I was a kindred spirit as she was going through this painful divorce, and she liked Face Value and she thought I’d understand her. I picked the songs with her – or for her, actually. That whole Something’s Going On album is great.

Only Paul McCartney and Michael Jackson have sold more records than you as a solo artist, so it must have been impossibly hard to choose material. Don’t you end up thinking “this will sell”, rather than “this is good” as your main concern must be to maintain your success?

You can’t help it. You can’t help but judge it by what position it gets to. Both Sides fell through the cracks a bit – I mean, it still sold eleven million copies. But I was very aware that everyone wanted me to go back to doing You Can’t Hurry Love and Sussudio, and here I was being serious and dark. People were saying: “You’ve lost your sense of humour, Phil.” People didn’t know what to make of it.

You were deeply unfashionable for a while, so how did it feel when you started getting support from the hippest quarter imaginable – Kelis, Ol’ Dirty Bastard and the Wu-Tang Clan?

I felt good about it – my people! Those R&B artists didn’t have all that conditioning, they didn’t have the rock critic backstory, and it’s refreshing. What’s written in The Sun goes everywhere; what’s written in the Philadelphia Inquirer stays in Philadelphia. So they’re not as aware of it. They don’t have the conditioning and the bias.

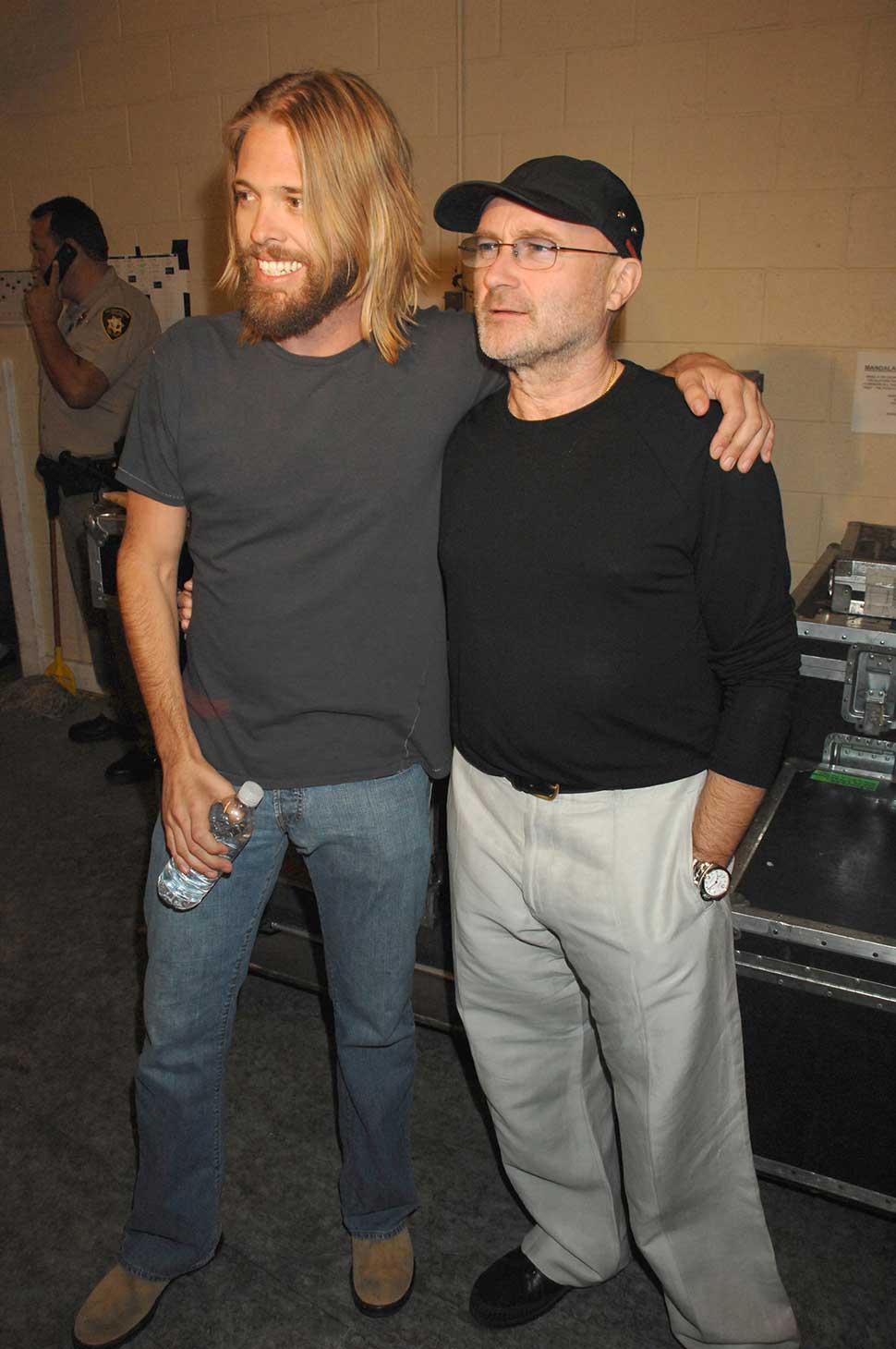

And Taylor Hawkins of the Foo Fighters wrote you a note…

He wrote me a lovely email: “Us in the Foo Fighters, we think the world of you. Please don’t feel bad about anything.” I’d done a thing in Rolling Stone which echoed round the world. I’d spent three days with this journalist, and we started talking about things… They were saying: “When three marriages have gone wrong and you’re not living with your kids, then sometimes… it’s a dangerous word to use, but have you ever felt suicidal?” “Yeah, I have.”

And people rang me up and said: “Don’t say that! What are your kids going to say at school?” There was a picture of me with Davy Crockett’s rifle and an axe. I thought it was lovely that he’d taken the time to write.

You said you were going to retire, and did so for a while, and now you’re not. What happened?

You say something one day and it goes around the world. I retired so I could be at home with the kids. Then my wife left me and took the kids – they moved to Miami – so I found myself in a void with no work. But I didn’t really want to work, and the kids weren’t there.

That sounds terrible.

It wasn’t particularly nice. I had a big hole in my life and I started drinking. And I wanted to stop so I could be with my kids. I also wanted to stop so that I could maybe do something else – I didn’t know what – though I felt l deserved the right to do nothing. All this stuff happened. The ear thing was in 2000 – I lost my hearing in my left ear – and then [waves arm painfully] the arm [a spinal injury affected his nerves in 2009, making it impossible for him to play the drums]. I had various operations. I still can’t play, but it’s better than it was.

Did you stop drinking?

Oh yeah. I haven’t had a drink for over three years. I nearly died from the damage, organs starting to break down. It was a series of things and I just kind of felt I want to be someone else. I’m a man of my word but, at the same time, there’s a hole where that used to be and I might as well do something.

Any regrets?

Not really. The serious things would be: “Would you try a bit harder at a marriage?” But things lead to other things. There’s a few people I’d love to have worked with – Miles Davis would have been nice, Aretha Franklin would have been nice. My daughter told me it was dangerous to stop working – “It’s part of what you are, you’re a writer” – and I realised it was important. What’s nice is I now realise people miss me.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 2017.